A journal for storytelling, arguments, and discovery through tangential conversations.

Thursday, September 5, 2024

|

Maude Johnson

Everyone has a different perspective and tolerance to workload. My vision of the art world has changed over the ten years I’ve been contributing to it. While it has a lot of positive aspects (or else I wouldn’t work in this field), I feel like it is based on idealized beliefs and unhealthy work ethics. If you’re employed by an institution, you’re expected to work full-time and visit exhibitions/attend openings in the evenings or weekends. There isn’t a lot of flexibility in terms of schedule and the pay rarely makes it possible to work part-time. I always had a good work capacity, but it led to a lot of stress layered in my body. I wasn’t very aware of the consequences that this could have on my mental health and in the fall of 2019, after a busy year of work, I burnt out. Five years later, I’m not sure if I fully recovered from it.

Wednesday, August 28, 2024

|

Nic Wilson

I know a lot of things about Audie Murray. I’m not sure how much of it is relevant to her art practice. I know her brother works on trucks in his spare time and I know what high school she went to. She has told me about her dreams. I know her child’s name and how she takes her coffee. I know how her kitchen is arranged and what is in the fridge: Babybel cheese, firm tofu, and at least three varieties of berries. She told me that when she is depressed and the idea of cooking food is unimaginable, she eats cubes of tofu with nutritional yeast. It is also one of her son’s favourite things to have for lunch. I often wonder how much I can know about someone’s art based on being friends with them. Murray grew up on Treaty Four land in oskana kâ-asastêki (also known as Regina, SK). She is a Contemporary Cree-Métis artist with community connections in Lebret and Meadow Lake.

Tuesday, August 20, 2024

|

Pychita Julinanda

In Indonesian, we have an idiom to describe a person like Riksa Afiaty: kecil kecil cabe rawit. Kecil means small. Cabe rawit is a type of chili that really stings. The idiom means to describe a small person who has an astounding energy and capabilities not to be underestimated because of their small figure. Riksa talks for hours during the interview, with almost nothing to be left unmentioned, and could go on for even longer if she didn’t have to run on other errands. I met Riksa for the first time at KUNCI Study Forum & Collective, a place where we often warmly gather. I was visiting Yogyakarta, and for the first time I got to know the people in the city’s arts scene. She hosted me in her house, and that was where the magic happened. She and Theodora Agni, her partner-in-crime, hosted me so well, and they listened well to my concerns when we talked for hours about the contemporary arts scene. I didn’t know how accomplished they both were, and I surely hadn’t known a lot of Riksa’s curatorial track record until I thought I should be in conversation with her.

Thursday, August 15, 2024

|

Shazia Hafiz Ramji

I like white paintings, and this gives me anxiety. Kazimir Malevich. Robert Ryman. Michael Buthe. These makers of white paintings are synonymous with high art made by white men in the tradition of minimalism that has come to be regarded as pretentious, elitist, and transcendent. What does it mean for a racialized queer woman like me to like white paintings? I was recently reading the poet Kazim Ali’s new and selected works, Sukun, and was relieved to find that he too likes white paintings, specifically those by Agnes Martin, the Saskatchewan-born, Vancouver-raised, America-educated artist known for her “grids” – large square-shaped canvases primarily featuring horizontal lines.

Monday, August 12, 2024

|

Laura Demers

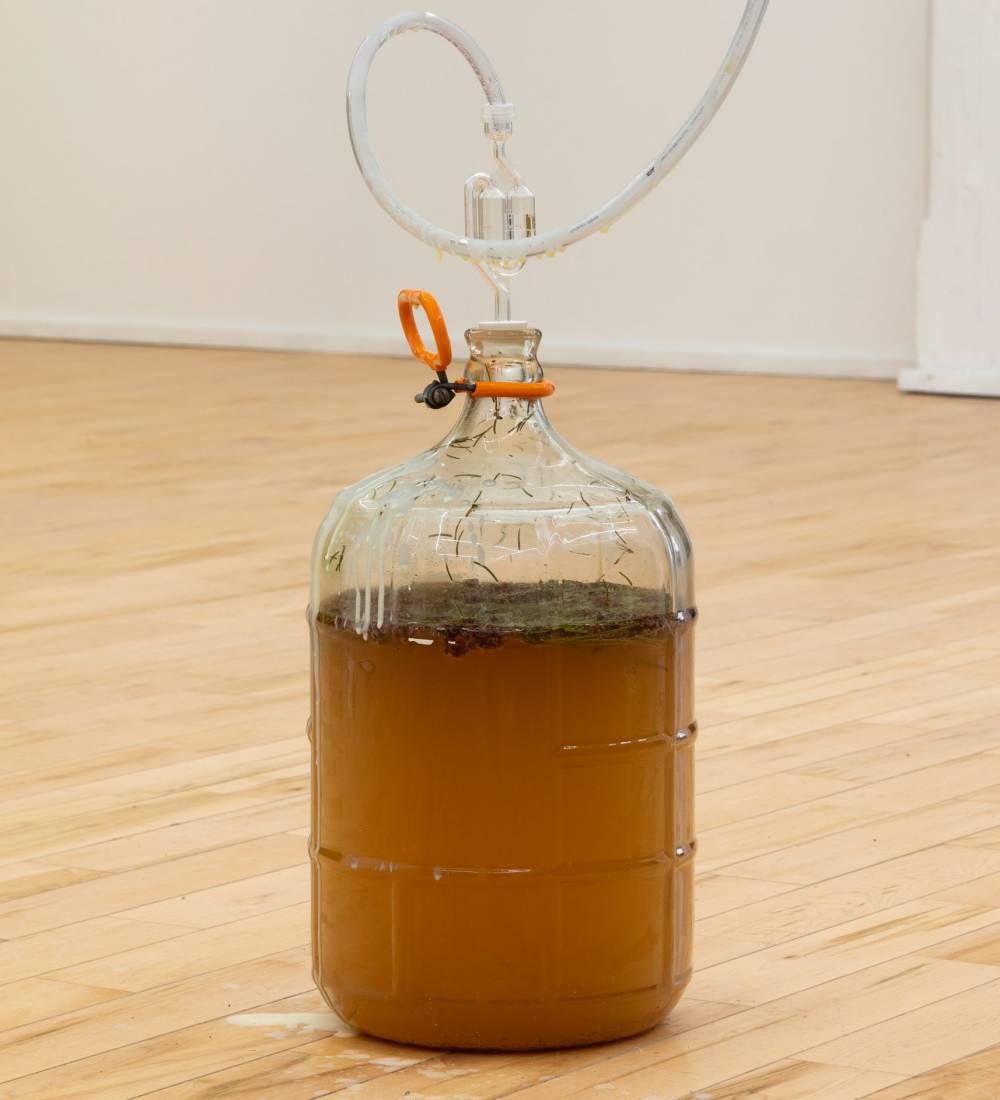

A milky, earthy aftertaste lingers in my mouth. An egg-sized lump of fresh butter sits in the palm of my hand, roughly enveloped in bark and moss and zealously held together by twine. My bundle is ready to be buried in the mire. Hamilton-based artist and curator Maria Simmons creates and nurtures sculptural installations that function as living ecosystems unto themselves. Last January, we had a chance to reconnect during a bog butter workshop and tasting, which Simmons hosted as part of a series of food-based artistic interventions presented by the Creative Food Research Collaboratory. Gathered around simple foods — bread and butter — we sampled the artist’s bog-aged Lactantia® and created our own butter vessels to re-embed in the muskeg come springtime.

Tuesday, August 6, 2024

|

Ainsley Johnston

Preservation has two meanings: keeping something of value intact, protected, and free from decay, or, alternatively, preparing food for future use by preventing spoiling. To preserve ideas, things, and places is to slow the passing of time to maintain their original state. Preserving food, however, is to transform it. For example, through fermentation, food can be preserved via a metabolic process that generates new products from sugars through the absence of oxygen and the introduction of microbes. Static or active: to embalm or to pickle. The act of preserving spaces and objects is historically that of the embalmer, but, in a zymology of architecture, fermentation transforms them anew. In 2019, I worked in an architectural archive, where sketch models, material experiments, drawings, furniture prototypes, books, and artworks lined three floors of wood and acrylic vitrines: a wunderkammer of “waste products” of the architectural process. Inoperable windows and blinds were permanently drawn. I envisioned the contents of the archive fermenting, ideas and concepts transforming as people extracted new possibilities from the leftovers of architectural thinking.

Wednesday, July 31, 2024

|

Gabrielle Willms

Owen Toews’s debut novel Island Falls (2023) is hard to describe. Half tale of unfolding friendship, half clinical report of a segregated mill town in the Canadian prairies, the enigmatic text plays with genre and form, raising questions about how space is produced and contested. The result is both charming and unsettling. Characters wrestle with how to respond to the violent structures that surround them and never really figure it out. In the end, we’re left to ponder the thorny relationship between trying to make sense of things and actually creating something better. Overall, the effect is galvanizing. Toews invites the reader to join him in the murk by asking timely political questions without prescribing answers.

Wednesday, July 24, 2024

|

Chigbo Arthur Anyaduba

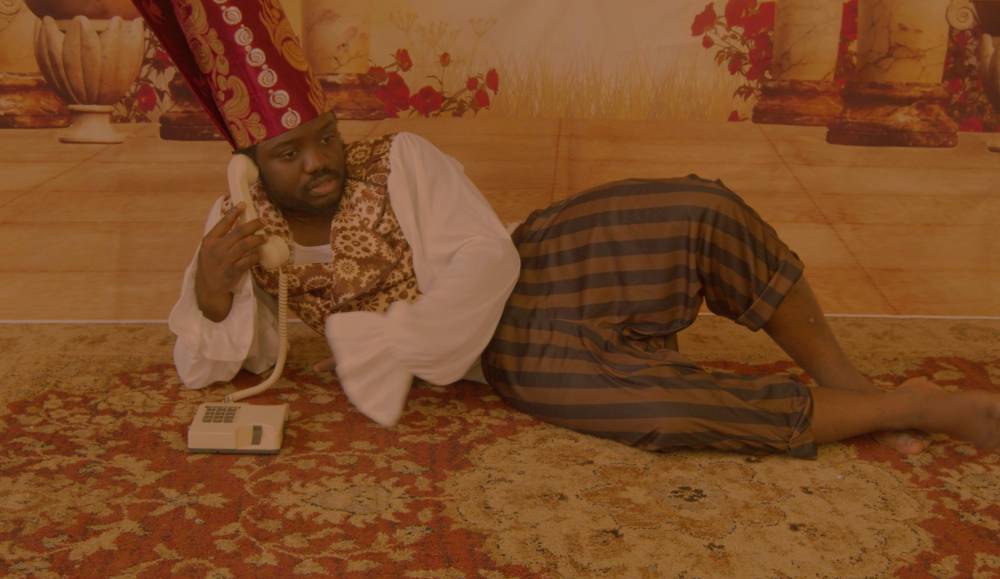

If there’s ever such a thing as a national character, Nigeria’s must certainly and unarguably be the bombast. To describe it in Nigerian: the bombast is that figure of ostentatiousness, affected magniloquence, a la-di-da of pomposity, full of jaw-breaking verbism and mouth-tearing prolixism. This figure by its manner and act is the victorious hero in a drama of the excess. Be it in its language use, its gestures, its carriage, its aura, its gastronomic exertions, its gait, and so forth, it’s all about immoderation—that surplus of sound and act. Bombasticism is the protagonist of just about any facet of the Nigerian society—politics, economics, religion, popular culture, education—a reason I believe it’s become the quintessential Nigerian character: at least of the contemporary time.

Tuesday, July 16, 2024

|

Su-Ying Lee

Amy Ching-Yan Lam and I look over the menus at a packed cha chaan teng (Hong Kong-style diner) in Markham, a suburb of Toronto. In the background are sounds of clattering dishware and Cantonese conversations. People are crowded into the small entryway as they eagerly await a table, glancing at diners who might be finishing up their meals. The energy in here is frenetic, but not unpleasant. Lam speaks Cantonese. I don’t. In this setting, the language conveys ease and maybe belonging, but is not required for ordering our midday meal. Descriptions of the dishes are written in Traditional Chinese (as it would be in Hong Kong) and in English (as it sometimes would be in the former British colony). Customers are guided by numbered pictures. The plastic-coated menu presents us with glossy photos of classics like pineapple bun sandwiches, baked meat and cheese casseroles served over rice, and instant noodles with a list of add-ins—the original fusion foods.

Thursday, July 11, 2024

|

Kaya Noteboom

Fungi are everywhere. I’m not the first to say it, but I want to be the last. In February, Triple Canopy published a series of essays surveying the ongoing proliferation of fungi-inspired culture. Mushrooms, with their pleasing color palettes and subtly salacious shapes, have been made into plushie toys, decorative patterns for dish towels and puzzles, and vibey graphic tees. Mushrooms, specifically the reproductive fruiting bodies of fungi that we can see protruding from soil or downed trees, are predictably easy to aestheticize. There are other parts such as mycelium that are aestheticized too but in different ways. These fine fungal threads are similar to roots forming networks underground that are largely out of sight. Unlike their squidgy counterparts, mycelial networks can’t be rendered into cutesy anthropomorphic characters. Instead, they’re more susceptible to conceptual aestheticization through language, social sciences, philosophy, and critical theory. Rather than make fungi appear more human as representations of mushrooms are prone to, mycelial aesthetics achieve the opposite.

Monday, July 8, 2024

|

Lindsay Inglis

M.E. Sparks is an artist and educator based in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Treaty 1 Territory. Born in Kenora, Ontario, Sparks completed her MFA from Emily Carr University and her BFA from NSCAD University. She has received numerous awards and grants for her work from the Canada Council for the Arts and the BC Arts Council, among others, has been involved in several international residency programs, and has exhibited internationally.

Sparks’s practice is deeply rooted in the history of painting. As an art historian, I was eager to speak to her about her influences and how the past continues to inform the present. My interests as a historian are primarily rooted around the birth of modernism, just as Spark’s often takes inspiration from modernism. In preparation for this conversation, I read through exhibition texts, interviews, and watched old panels where Sparks spoke about her work. Throughout this research, one thing in particular stood out to me: she was very well-spoken and could clearly articulate the thought process behind her work as well as her perspectives on the world around her. With this in mind and our overlapping interests, I was both nervous and excited to speak with her.

Tuesday, June 25, 2024

|

Iacopo Prinetti

In a recent article for Airmail Magazine, a U.S.-based online lifestyle publication, the artist Laila Gohar presented her formula for hosting the perfect party. It included, in random order: Laillier Blanc des Blancs champagne (“holiday water”), crystal cups (“so wide that almost seem like swimming pools”), cotton-linen tablecloths (“elegant yet not too uptight!”), and mother-of-pearl spoons (“perfect for caviar, but also for ice cream or sorbet”). In Gohar’s opinion, these chiselled details aim to create an atmosphere “relaxed yet considered, easygoing but layered.” I would be lying if I said that I’m not mesmerized by the atmosphere Gohar depicts, flawlessly combining the irony of Madonna’s “Material Girl” with the decadence of the infamously chic NYC restaurant La Cote Basque, which was immortalized by Truman Capote in his unfinished book Answered Prayers. In the current times of growing violence, uncertainties, and genocide, this champagne-filled, oyster-flooded ambience is where I would like to drown.

Thursday, June 20, 2024

|

Amy Fung

In response to the Spring Equinox, Public Parking Editorial Resident Amy Fung invited multidisciplinary cultural workers Indu Vashist and Cecilia Berkovic to engage in a mindful and honest conversation on themes of cycles, practice, violence, and endurance to mark this year’s Summer Solstice. Meeting and working in the Toronto arts scene in the 2010s, Berkovic, Fung, and Vashist reflect on the present era of what it means to be alive.

Thursday, June 13, 2024

|

Olajide Salawu

In a new documentary film on his life and politics, Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu is in a Toyota SUV when the camera pans closely to his face revealing his lanky form even in his cardigan. His red beret — the veritable and allegorical element of his political struggle — hangs on his knee in the brief foreshadow. Along with other comrades of his political persuasion, they are gearing up for a campaign against one of Africa’s last dictators. Shortly after this scene, Ssentamu asks if his comrades are ready for the outing in solidarity, and a hymn follows. They all chorus their ache of their country’s political hostage and tempest but register their assurance of victory in the end. It is an overture that summarizes the intention of the film: to familiarize the audience with the massive energy Ssentamu has gained from his people. We see him lead an entourage of motorcyclists through a market alley and standing high with his red beret as an unflagging radical raising his fist in struggle. However, we would soon learn that opposition comes at a price; people are seen seeking safety in every corner as sporadic shootings heighten the tempo and pathos of the film. Ssentamu, known as Bobi Wine, his stage moniker as a musician, has become an African symbol of liberationism. And beyond his music, has been in the fierce field of Ugandan politics. In the last decade, Wine’s personhood has edged out as a critic, ideologue, and a credible antagonist of Yoweri Museveni.

Monday, June 10, 2024

|

Gabrielle Willms

Theo Jean Cuthand’s videos are full of good lines, but there’s no time to dwell on them. They’re delivered without pause, almost matter of factly, in unhurried monologues that span the video’s run time. In 'Extractions' (2019), he describes the terrifying lumber scrap incinerator in Merritt, where he spent four intolerable months as a teen, “like something in a Disney movie symbolizing death and anguish.” Earlier, over footage of a series of explosions in an open pit mine, he notes benignly, “I like to think there are alternatives.” In Less Lethal Fetishes (2019), he uses gas masks to meditate on kink culture and the art world’s toxic relationship with industry. As the video concludes, Cuthand laments the loss of a “simpler time” when he could just appreciate the “horny joy of watching a woman wearing a gas mask while in bondage” and not consider its political implications.

Wednesday, June 5, 2024

|

JiaJia Fei

The intersection of art and fitness is so small that I can only name a handful of artists who deliberately engage with the subject (all of them male, of course). It is a topic that is so rarely discussed in my world–the art world–that it took a global health crisis for me to finally begin to take control of my own health, and to introduce an entirely new vocabulary into my vernacular. Four years later, I now find myself speaking fluently–and passionately–about hypertrophy, isometric movements, and macronutrients. Before I became the person I am today–the person who works out everyday and whose identity is now defined by the fact that she can do 10 pull-ups and deadlift twice her body weight–I never exercised. Though I had been a dedicated cyclist in New York City for the last 15 years, not once did I ever step inside of a gym, nor did I ever pick up a weight. The idea of excelling in sports or fitness was just not a part of my personal brand; I was the creative one, the subversive one, the eccentric, artsy one. Going to the gym was just so mainstream. Plus, I (convinced myself I) didn’t have time.

Tuesday, May 28, 2024

|

greta hamilton

The presence of soil in contemporary art can be thought of as continuous with the Earth Art movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Iconic works of this era include Andy Goldsworthy’s stone cairns and cracked clay walls; Michael Heizer’s geologic fissure in the Nevada desert; Walter De Maria’s Earth Room sculptures, in which the artist scattered soil across gallery floors; and Robert Smithson’s mud and basalt jetty in Utah’s Great Salt Lake. What differentiates contemporary uses of soil from these material predecessors, however, is the more recent association of soil with climate change, colonization, and resource scarcity, emphasized by environmental catastrophe.

Thursday, May 16, 2024

|

Lauren Fournier

Tazeen Qayyum is a Pakistani-Canadian artist based in Toronto. She was trained in the South Asian and Persian traditions of miniaturist painting before she began the mixed-media practice which she sustains today. During the month of Ramadan, I wanted to speak with her about what it is like to be a practicing Muslim as well as a contemporary artist working in Canada. I was also interested in her experience making work that is conceptually driven and shaped by culture and faith. For example, in her iconic archival ink on paper works, Qayyum repeats a word written in Urdu script to form concentric circles, which the artist inscribes through a repetitive movement that is prayer-like. The artist chooses words stemming from concepts found in her Muslim faith. Words like khayaal (care), sakoon (calm/peace), sabr (patience), zameer (conscience), yaqeen (certainty/belief), and fikr (concern/thought) have featured in her work, as well as more explicitly political words like brabri/bartri (equality/privilege), which the artist made in direct response to the 2020 resurgence of Black Lives Matter.

Monday, May 13, 2024

|

Tammer El-Sheikh

I was pleased to hear that the incision would run from one side of my neck to the other, following a natural wrinkle. The original plan was to begin a descending cut under one ear for several inches, then proceed across the neck and back up to the other ear – a “horseshoe incision” that wouldn’t age as well. In any case, I was facing a bilateral neck dissection to remove a large malignant tumor on my thyroid and an unknown but significant number of affected lymph nodes in the area. To my relief, this was a curative operation with a high rate of success and a prognosis for a statistically “normal life,” which, during the first several months post-op, felt anything but normal. My old voice was gone, and I didn’t know what to make of the new one. Although vocal paralysis is a risk in a total thyroidectomy, I had avoided this fate thanks to sophisticated nerve-monitoring gadgetry, but I emerged from the operation with a kind of breathy cookie-monster voice that, two years on, has settled somewhere in the vicinity of a fashionable vocal fry.

Monday, May 6, 2024

|

Michael Martini

What if grants worked like insurance policies? Artists would buy into them and on the off-chance an opportunity actually struck them the granting body would be obligated to pay out and make the opportunity happen. Insurance, of course, is based on low odds. A payout is a form of surrender: “Fine, you win. Here’s your money.”

The Canada Council for the Arts funded approximately 15% of Creation projects last fall . A heads up about their skeletal wallet would certainly have been helpful to the other 85% of applicants. There’s some commiseration to be done here. The applicants certainly spent hours upon hours over lukewarm coffees amping up their ideas, their CVs, and converting them into PDFs to boot. here is a type of nudity that goes into grant-writing, not just administrative nudity (“here’s how poor I am, colour-coded for your convenience”) but also emotional (“here what I care about, deeply; here’s who I am, deeply; may I please have a cookie now?”). Click here to confirm we can share this with the government however we like. This time around 85% of applicants sent their nudes and got blocked.

Wednesday, May 1, 2024

|

Ashley Culver

On the second Monday in December, I click the link, open a window, and see myself. Instinctively, I adjust my posture. Anne Low has joined your meeting room. A couple of months earlier, I visited Low’s solo exhibition Bury Me at Franz Kaka on Dupont Street in Toronto. The show featured five works that engage with the domestic and the decorative. Inspired by pre-industrialized cloth samples, Low’s woven textiles are presented in sculptural forms; each work gestures towards the material evidence of housework: cleaning, mending, storing, tending, and washing. An artist-weaver, Low works in sculpture, installation, textiles, and printmaking. After completing her fine art education at the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design and later, at the Royal College of Art, Low studied at the Marshfield School of Weaving in Vermont in the summer of 2012, a place to which she has often returned.

Tuesday, April 23, 2024

|

Shi-An Costello

My work as an artist allows me to make some sense out of my life's material chaos. The process of making art does this for me because, to me, art is the capturing, reordering, and if ultimately successful, the framing of the chaos of life into something worth saving. My artistic creations allow me the opportunity to reframe my additive universe of experiences.

People are endlessly generative, creating more and more material through the entirety of their lives. Be it words, notes, gestures, sounds, or brush strokes. A unique quality of art is that we can create a thing that lasts long past our own brief lives. To find and record the final thing, whatever that thing might be, is to make a frame, literal or figurative, around a small portion of the untamable force of human creation.

Monday, April 8, 2024

|

isra rene

I have thought a lot about whispers. I once asked a friend if they noticed whispers in their life and they looked at me with sheer terror. It dawned on me then that I needed to map this territory, or at least humbly attempt to follow it’s inchoate thread. My thoughts wander around the (non)purpose of a whisper. I think about its scale. I think about the disintegrated absences left by a whisper. I think about its atonal architecture in active decay and how, as it passes from one source to the next, there is always a surprise. From addition to omission, whispers will never fail to surprise you. I remember as a child I loved to play the Telephone Game. It is an intimate game of transmission chaining, or otherwise known as whispering. In the game a message is whispered from one person to the next, it ripples until it reaches the final player. That person has the ephaptic duty of telling the group what transmission they received.I remember as a child I loved to play the Telephone Game. It is an intimate game of transmission chaining, or otherwise known as whispering. In the game a message is whispered from one person to the next, it ripples until it reaches the final player. That person has the ephaptic duty of telling the group what transmission they received. Through the sequence of person-to-person accumulation the final arrangement is almost always partially vacant of the original constitution. This game is a performance of intimacy, listening closely, and deciphering. It is the act of noticing at the most discreet level, knowing that distortion is inevitable, but unearthing new meaning in it and welcoming it all the same. I find myself positively obsessed with the formation and de-location of a whisper.

Wednesday, April 3, 2024

|

Emily Zuberec

Summer 2023 was eventful for the stretch of avenue du Parc between avenue Fairmount and rue St. Viateur in Montreal's Mile End neighbourhood. Each Thursday between June 1st and July 8th, photographers Fatine-Violette Sabiri and Paras Vijan welcomed visitors into the world of One by Two, their serialised exhibition at Galerie Eli Kerr. These vernissages came to punctuate the lives of many of us in the neighbourhood's creative community; our attention was oriented towards the gallery space and the sidewalk benches that flank the entryway, as we convened in a way that was profound, joyful, and sorely missed once the exhibition closed. That was the experience for the audience — backstage, Sabiri and Vijan worked away diligently and playfully at creating a photography show that, in its durational and evolving nature, put forward a definition of collaboration. Simultaneously, the exhibition rendered visible the parallel mechanisms of friendship and photography, both of which, like collaboration, hinge on time-elapsed.

Monday, March 25, 2024

|

eunice bélidor

I am sitting on the windowsill of my studio in the Résidence des Récollets, in Paris. It is 22h12, Paris time, and I am wondering if I should spend the rainy day tomorrow working on various curatorial projects waiting for me back home in Montreal, or if I should wake up early and go to my hot yoga class. Ever since I knew I was coming to Paris, I searched the web to see if they had the type of hot yoga I have been doing for the last 15 years. The studio in Montreal no longer exists, and my body and mind have been aching ever since.

I started my yoga practice at 17 years old: my yoga teacher would come once a week to my high school to teach us beginner’s Hatha Yoga. Back then, I was a weird kid – meaning it was odd to other Black students that I would do yoga, not eat meat, devour Madonna biographies, and read about Buddhism. But what yoga gave me was a gateway to mindfulness and creativity, an outlet to think beyond the education and the system I was brought up in. Yoga opened my eyes to new perspectives and allowed me to think of myself as something or someone else.

Wednesday, March 20, 2024

|

Amy Fung

I had been thinking of cycles before consciously becoming aware of completing one. I turned 42 last Fall, which can be divided as six cycles of seven, or two cycles of 21, or 14 cycles of three, or any number of reversals. Throughout my 20s, I was borderline obsessed with my Saturn Return, which is when you complete four cycles of seven, a spiritually significant number through most of human history. Seven is a number that appears and reappears from the Sumerians’ seven-branches in the Tree of Life and the institutionalization of the seen day week to the seven heavens of the Qu’ran, and the Talmud to Hinduism to the seven virtues of Buddhism and the Catholic’s seven sacraments and seven sins, and so on. Music falls across seven major note scales (do rei me). The spectrum of refracted light is expressed in seven colours (roy g biv). From tip to tail, there are seven chakras from crown to root.

Thursday, March 14, 2024

|

Micaela Dixon

A code of conduct is a list. It can be short or long, normally between five to seven points. It enumerates a certain set of behaviours that are appropriate in a given setting. Sometimes behaviours that are not appropriate are listed too. It is sort of the x and y of socialisation. It plots a space between appropriate and inappropriate behaviour. But it is entirely movable and depends on a given situation, so some would say that it’s site specific. The first time I meet artist, Ethan Murphy is on a Zoom call sometime in late 2021, but technically the second time we meet in person is on Fogo Island in Newfoundland & Labrador. I wait for him in an unmarked parking lot in Joe Batt’s Arm and he arrives fresh off the ferry in a 2004 red Toyota Tacoma, blasting music and a large smile.

Wednesday, March 6, 2024

|

Jasper Wrinch

I’ve been listening for the sound of a drill driven under. It’s coming any day now. The rumble and the crack of an old vein being revitalized. Recovering ounces that were overlooked by the old timers. A mechanical curtain to the wind sweeping through the willow, so that the rust can once again be followed into the rock. Uncovering an old route into the mountain side, widening the adit, digging that hole deeper. Back into the wrecked earth, seeping. All this in a town sitting in a bowl at the end of the highway. At the head of a lake whose tarnished shore had its contours changed in a boom and whose sediment settled into an uneasy equilibrium in the bust. This generational bust it has been wallowing in. Populations un-ballooning, buildings slumping under the snow load, paint peeling and scraped away. To be refreshed by colour and sound added back into a landscape wrung. Footings finally squeezed under the foundationless mine homes, constructed quick and left to warp in the shifting ground, to hold them up for longer than the boom ever was. They say this is a way out, but I could have sworn I saw the theatre full on a Wednesday night, all within the bust. Not significant.

Tuesday, February 27, 2024

|

Hannah Doucet

When rewatching old artist talks of AO Roberts in preparation for our conversations I came across a quote of theirs “I have so much to say but I don’t want to tell you anything at all.” There's a tension within Roberts’ work between revealing and obscuring, a generosity to the viewer as well as a distrust. AO Roberts is a Winnipeg-based multidisciplinary artist working in sculptural installation and sound. They have also performed in numerous noise projects and punk bands such as Wolbachia, Kursk, Hoover Death, and VOR. During the winter of 2022, I chatted with Roberts several times on Zoom, myself in Toronto, and Roberts in Winnipeg. Throughout these conversations, we touched on many of the diverging threads in Roberts’ work: medieval histories, anti-capitalist frameworks, chronic illness, and the tactile and sonic qualities of language.

Thursday, February 15, 2024

|

Kalina Nedelcheva

Lens-based artist and filmmaker Zinnia Naqvi and I met by chance during the 2023 Mayworks Festival where she presented 'The Professor’s Desk' (2023), a project that told the stories of four cases of discrimination in Canadian universities. At the time, I was a Teaching Assistant at OCAD University and the outgoing Executive Director of Graduate Studies for the OCAD Student Union; the name of Naqvi’s exhibition piqued my interest due to my political involvement with the institution and my desire to research and work toward better futures for students and faculty. Part of my job was to navigate and mediate conflict, to anticipate and strategize campaigns, and to work toward building a more equitable academic and workplace environment. To do my job effectively meant that I needed to nurture 360-degree awareness—to analyze present conditions, to acknowledge the past, to plan for the future. Naqvi’s 'The Professor’s Desk' looked at the past but projected into the future.