A journal for storytelling, arguments, and discovery through tangential conversations.

Wednesday, July 24, 2024

|

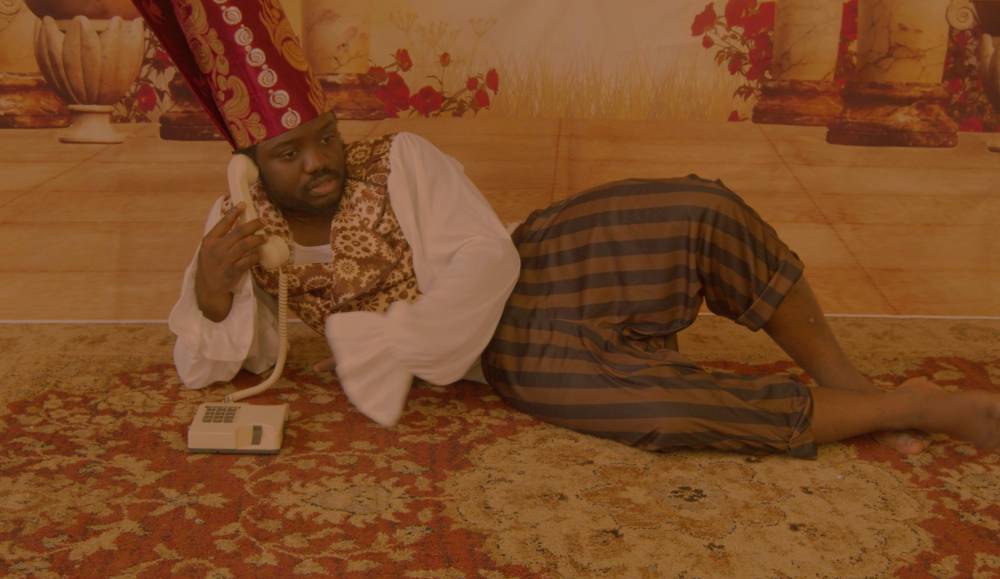

Chigbo Arthur Anyaduba

If there’s ever such a thing as a national character, Nigeria’s must certainly and unarguably be the bombast. To describe it in Nigerian: the bombast is that figure of ostentatiousness, affected magniloquence, a la-di-da of pomposity, full of jaw-breaking verbism and mouth-tearing prolixism. This figure by its manner and act is the victorious hero in a drama of the excess. Be it in its language use, its gestures, its carriage, its aura, its gastronomic exertions, its gait, and so forth, it’s all about immoderation—that surplus of sound and act. Bombasticism is the protagonist of just about any facet of the Nigerian society—politics, economics, religion, popular culture, education—a reason I believe it’s become the quintessential Nigerian character: at least of the contemporary time.

Thursday, July 6, 2023

|

Chigbo Arthur Anyaduba

If ever there’s such a thing as the cultural character of an epoch—that is, a quality or cultural attitude that distinguishes a historical time from another across spaces and places—the contemporary epoch, at least in the West and perhaps in Africa, will be best characterized by that complicated concept called trauma. Trauma has become the “cultural script” of our time, writes Parul Seghal in a New Yorker essay titled “The Case against the Trauma Plot,” “a concept that bites into the [cultural] flesh so deeply it is difficult to see its historical contingency.” The cultural fascination with trauma, while best understood as one of those spin-offs that developed in response to the enduring legacies and present conditions of imperial violence and oppression, has, according to critics like Seghal who have been critical of the trend, spawned a dull literary practice in the present that is underpinned by a simplistic vision of trauma—most especially in the West. This simplistic vision, which Seghal describes as the trauma plot, has largely manifested in contemporary trauma literatures as traumatic backstories or a chain of backstories that “flattens, distorts, reduces character [and our appreciation of complex experiences] to symptom, and, in turn, instructs and insists upon its moral authority.” It works essentially to pathologize just about any experience and narrow understanding of identity and social life to some idea of a traumatic beginning.

Wednesday, September 14, 2022

|

Chigbo Arthur Anyaduba

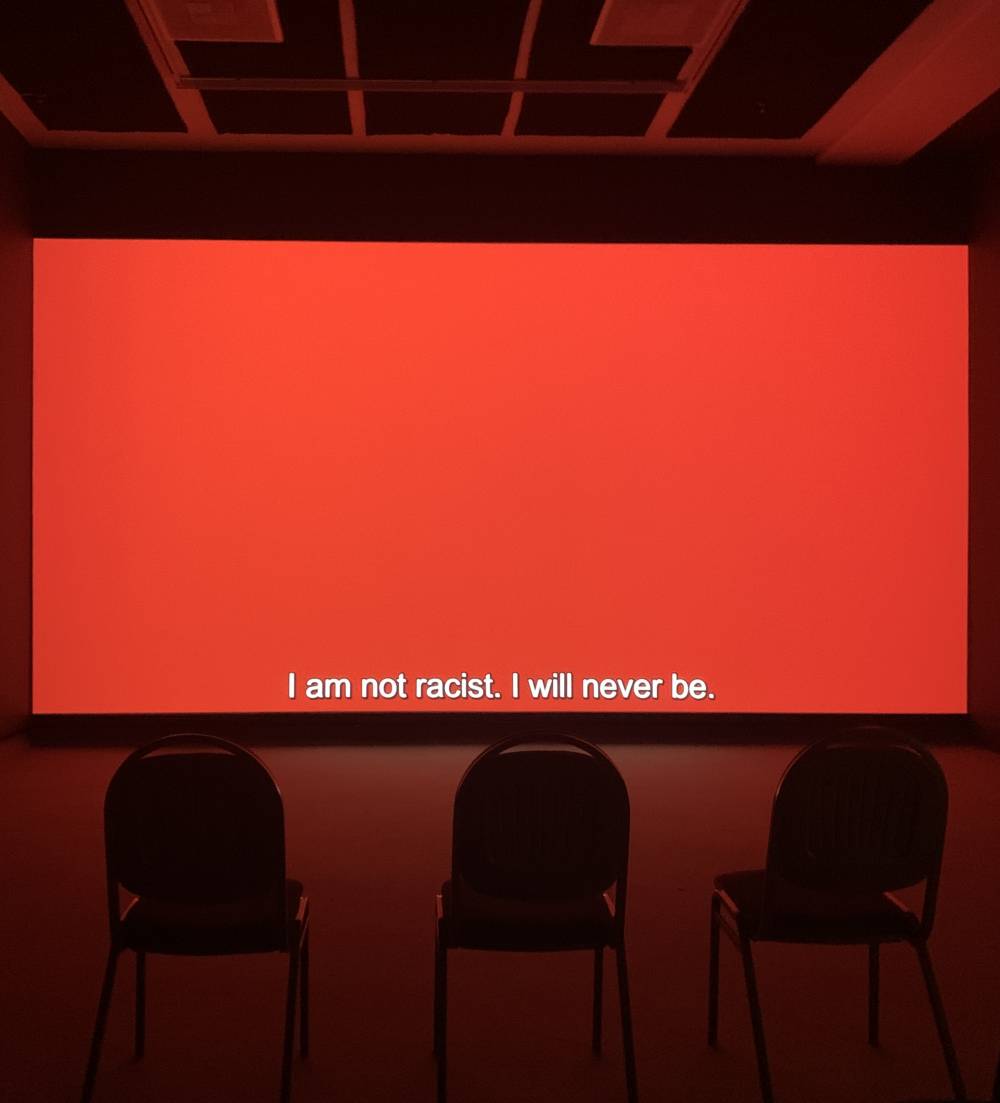

Africanists, as some of us have come to know them, are white academics who are experts of that monumental piece of fiction called “Africa.” It is to Africanists we owe a lot of our “knowledge” of Africa. They tour “Africa” regularly and return to Europe and North America to supply academic facts and knowledge about Africa and its peoples, animals, geographies, and whatnot. Their knowledge of Africa is never in short supply: they’re stupendously widely published in major Western academic journals and presses. One finds them regularly giving interviews to mainstream Western media on this/that crisis in Africa. The media call them experts of Africa.

Africanists are well funded; they can easily afford to spend years anywhere on the African continent researching Africa. Africanists have theories for just about any African problem. In fact, they invented African Studies and over the years grudgingly made allowances for certain African scholars to be considered experts in African Studies—but only once the bloody African scholars can demonstrate some fluency in the theories and vocabularies of engagement produced and circulated by Africanists.

Monday, April 25, 2022

|

Chigbo Arthur Anyaduba

Noo was a fashion blogger until June 2020. Then she wrote a piece on the removal of the infamous statue of English enslaver Edward Colston by Black Lives Matter protesters in England. Someone popular shared her blog piece on Twitter.

The viral blog post was her reaction to the language the media used in describing protesters’ removal of the statue. “They use words such as FALL, TOPPLE, DEFACE, TORN DOWN, TARGETED, VANDALIZE,” Noo wrote.

“These words work to turn the real act and force of violence on its head. They signal that protesters’ removal of the statue is a violent act—not remedial. Even more pernicious is the underlying meaning suggested in these word choices. The language of toppling and falling is loaded with grotty double entendre. In addition to calling protesters violent, this language positions the statue as a sovereign authority and protesters as its subjects. Rhetorically speaking, pulling down the statue becomes an act of rebellion—an insurrection—by subjects seeking to overthrow the sovereign. Such a cheeky use of language!”

So much has been written about media representations of the struggles of oppressed people that you get easily wearied reading any new thing. But when you read Noo’s post you were captivated by her idea that the language of media reports positioned colonial statues as sovereigns. It struck you that this language might inadvertently be describing a struggle against a condition of power exercised in excess. After all, besides their manifest presence in physical spaces marking land and time, statues appear to convey a sense of surplus presence. Their adamant visibility in the public sphere is a demonstration of power over physical and mental space. Could the protests against these colonial statues be coming from an equally tacit recognition of a condition of power so profoundly manifest, insuperable?

Thursday, August 12, 2021

|

Chigbo Arthur Anyaduba

In the Republic of Apology sorry can buy you anything. Can pay for anything. Those were the opening lines of your book on apology. When your editor Zach first read it, he said that etymologically-speaking “sorry” and “apology” were not neighbours. Apology was a statement of excuse, something put up in defence against accusations. That was how ancient Greeks understood it. Sorry, on the other hand, came from Middle English and expressed sympathy and a feeling of soreness or sorrowfulness. The operational form of the contemporary regime of apology, said Zach, had returned to the original meaning of the word [...] A few weeks after you sent your manuscript to Zach, he called, sounding excited. Over drinks, Zach said, I couldn’t help myself.Your manuscript inspired me to write a story set in your Republic of Apology. His story is about a man who personifies all the apology paraphernalia celebrated in the Republic. He apologises for everything; he greets apology, jokes apology, weeps apology. Step on his feet while in a bus he apologises with a smile. Yet, as it turns out, this man is a serial killer. Gentle in his approach and always full of apologies to his victims even when killing them. “I am so, so sorry that I have to kill you,” he always says to them, “it’s probably no fault of yours, eh. I can’t help it. I do not hate the fact you’re an aberration of nature, a bloody faggot, eh. But I have to say I am sorry it has to end like this, eh.” His last words to his victims were always: “You do not deserve to die.”

Zach was excited about his story. You asked him what the point was, exactly, about a serial killer who apologised to his victims.

The hollowness of it all, he replied.

You told him about an event you recently attended where the Prime Minister delivered an impassioned apology speech to Indigenous peoples. One man in the audience stood up and screamed at the top of his voice just when the Prime Minister had finished talking: “We got our apology! We got our apology!” The man wasn’t far from where you sat. You could see that he was crying as he screamed, almost losing his voice. You weren’t sure whether he was crying because of the Prime Minister’s apology speech or whether his “We got our apology” was meant as sarcasm. One way or another, you said, there must certainly be something in an apology that is more than hollow.

In the Republic of Apology where apology solves injustice, Zach said, it’s all the currency there is.