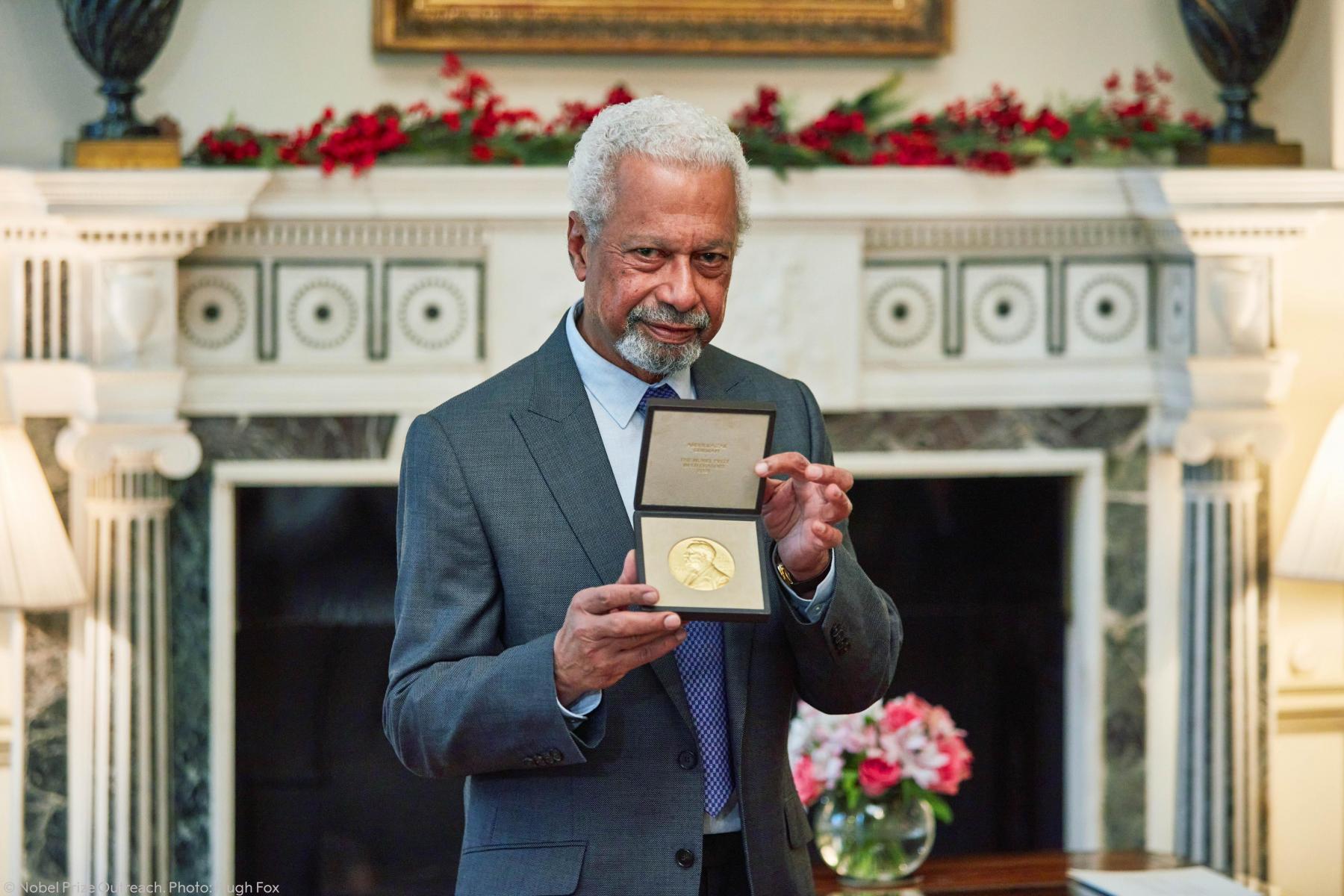

2021 literature laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah just received his Nobel Prize medal and diploma in London, United Kingdom. Image sourced from Nobel Prize Twitter.

On both the Anglophone and the Francophone sides, Africa was on the podium of literary delight in 2021. It is true as in the words of Samira Sawlani that African writers took the world by storm. Boubacar Boris Diop won the 2022 Neustadt International Prize for Literature for his book titled, Murambi: The Book of Bones, which explores the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. It is the fifth decade of the prize and Diop is among the few Africans who have won the prestigious award organized by World Literature Today of the University of Oklahoma. The Ghanaian writer, Meshack Asare, also was a recipient of the Children’s Literature category in 2015. Neustadt International Prize for Literature is considered one of the most prestigious awards only in proximity to the Nobel Prize, amounting to $50,000.00. More than the visibility benefits, this award would position Diop not only in the African literary market but across uncharted territories where his works have not been read or studied. Awards such as the Neustadt International Prize for Literature increase the literary fortune of writers in the publishing space. Boubacar has been writing for decades, winning numerous laurels. Yet some of his works which are not available in English may now be open to English readers, courtesy of the impact of the award. Mohamed Mbougar Sarr, a Senegalese writer, would go on to win France's oldest and most illustrious literary prizes, the Prix Goncourt, for La Plus Secrète Mémoire des Hommes (The Most Secret Memory of Men), and then adding Hennessy Book Award and the Transfuge Award for Best French novel. Tsitsi Dangarembga, the Zimbabwean writer and author of Nervous Conditions and Mournable Body received the 2021 PEN Pinter Prize and the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. For Dangarembga, awards such as the PEN Pinter Prize provides a generative moment for her works and enhancement of her vision and goals.

How can we theorize an African award culture that places indigenous African literatures also at the center?

I turn over Samira Sawlani’s alacritous phrase: when the storm takes off, who does it take along? Who does it leave behind? Who are the celebrated figures today? Who are those involved in the culture of compensation for their creative investment? The storm leaves behind more worries for African writers, if writers writing in non-colonial languages are included in the conversation. How can we theorize an African award culture that places indigenous African literatures also at the center? International awards continue to place-make and amplify Africans' status in global literary and cultural canons. Yet, the infrastructure of honor and award becomes problematic when its history is colonially flawed and when the rewarding body celebrates only the literary pieces written in imperial languages. For most parts, literatures originally written in African indigenous languages that have been translated are left out of this honorary practice. Awards such as PEN Pinter, Nobel Prize, and even Man Booker leave little room for literature written originally in African indigenous languages, where the literatures perish, the languages also perish. In addition, another major obstacle presents itself in the constant gaze towards the reward industry in the West: positioning literary and cultural production in Africa at the behest of the power and politics that reward evokes; outlining what is to be written, how it is to be written and when it is to be written. Nevertheless, such a predicament is asking us to recognize a prognosis: the continent needs to nurture a homegrown remuneration system that celebrates the extensive and dynamic space of African literature. There is a need for such a renaissance: an intensive restructuring and a call for commitments to invest in the literary and cultural industries in the continent. The future of African literature succeeds more when writers do not dominantly rely on the kindness of the West to quantify the value of their works. It flourishes because such a commemoration beginning from home is also redefining the history and erecting an inherent superstructure that safeguards against Western ideology.

In recent years, the Nobel Prize for literature has followed a more disparate rancour. The African literary giant, Ngugi wa Thiong'o, occurs as the usual public reference for the Nobel acknowledgement, across a major quarter of the African literary constituency who believed that he was deserving of the Nobel Prize. Each year, the media circulated news about his exceptional contribution to East African literature and the place of language in African literary production. Like the previous ones, this year came with its shock when Abdulrazak Gurnah was announced as the Nobel Prize winner for 2021. Two dimensions of arguments followed Gurnah’s victory. Many, including major literary powerhouses in the West, contended he was an obscure writer who was barely known even though he had been on the shortlist of Booker Prize before and has written many books. Others have maintained that Ngugi should have been allotted the prize and people hardly know Gurnah, and his identity as an African is even contestable owing to his migratory history.

Even though I have never doubted the power that the Swedish Academy wields across disciplines, one major point seems to elope the thoughts of the Nobel Prize debate pushers. The Nobel Prize is a postcolonial afterthought for Africa. Just like the Booker Prize, won by the South African writer, Damon Galgut in 2021, was created to re-energize global public appeal for British literature.1 Although the prize since the 1980s has gestured towards balancing the gap, it leaves room for further contemplation. The contributions to African literature cannot be theorized from African literature in colonial languages alone, the prize continues to ignore indigenous writers in African literary geographies. This brings us to the question of the colonial framework that canonizes only the voices producing literature in colonial languages; the tag of ingenuity fails to exist for those writing in Yoruba, Swahili, Wolof and other languages. And if it exists, it exists in tandem with historical dynamics that place African language and literature produced in it at a nonchalant threshold. Prizes need to bestow honor on literature written in indigenous African languages. The decolonization project begins with recognizing the primacy of indigenous language in the productions of literature, arts and culture.

The gaze of reward must be first a locally grounded and interior desire: a time to praise these icons of arts right from home. The project of decolonization that has gained currency takes a backward step if the reward industry from the West continues to determine the values and aesthetics of the African cultural and literary landscape.

An appraisal of this year’s ceremony of ignoring Ngugi while celebrating Gurnah begs the question it creates: should other African writers at the expense of Ngugi remain uncelebrated for their works and contribution to literature? More importantly, the problem has not always been that of reception of such awards and their colonial legacies. The theory that African writers or artists cannot receive plaques of honour from the West has its weaknesses. There is a dearth of durable and sustainable culture of reward in the continent that celebrates cultural and literary excellence. There has been a partial or total absence of such an institution of honour that cherishes the pedigree of works and intellectual investment in the growth of literary and cultural productions in Africa. But where there are systemic leadership challenges across the continent today and most countries remain imperial lackeys, the non-African institution of reward becomes the home and impediment that binds the artists and the writers with Western awards. And more importantly, where others are re-imagined and requited for their talents, the African artists are re-imagined alongside the continent, they exist as African artists while ignoring heterogeneity of the continent.

The gaze of reward must be first a locally grounded and interior desire: a time to praise these icons of arts right from home. The project of decolonization that has gained currency takes a backward step if the reward industry from the West continues to determine the values and aesthetics of the African cultural and literary landscape. Decolonization is yet to begin when Africa exists in the category of identity and race, but not talent. The tone of reward practice should not be inflected with inferiority, but recognize the diversity and dynamics of literature from the continent. Whenever an award such as Pulitzer, Booker, and others generates euphoria for an artist and writer, they come with their own caution. They ask us to reconsider the systemic failure that bedevils African reward industries and their epileptic presence. They want us to dismiss the current standard of African Prize’s such as The AKO Caine Prize exclusion of indigenous literatures in their compensation scheme. More genuinely, it envisages a future that is desperately needed to avoid living up constantly to the yardstick of the award in the West.