A journal for storytelling, arguments, and discovery through tangential conversations.

Monday, October 20, 2025

|

Nicolas Vamvouklis

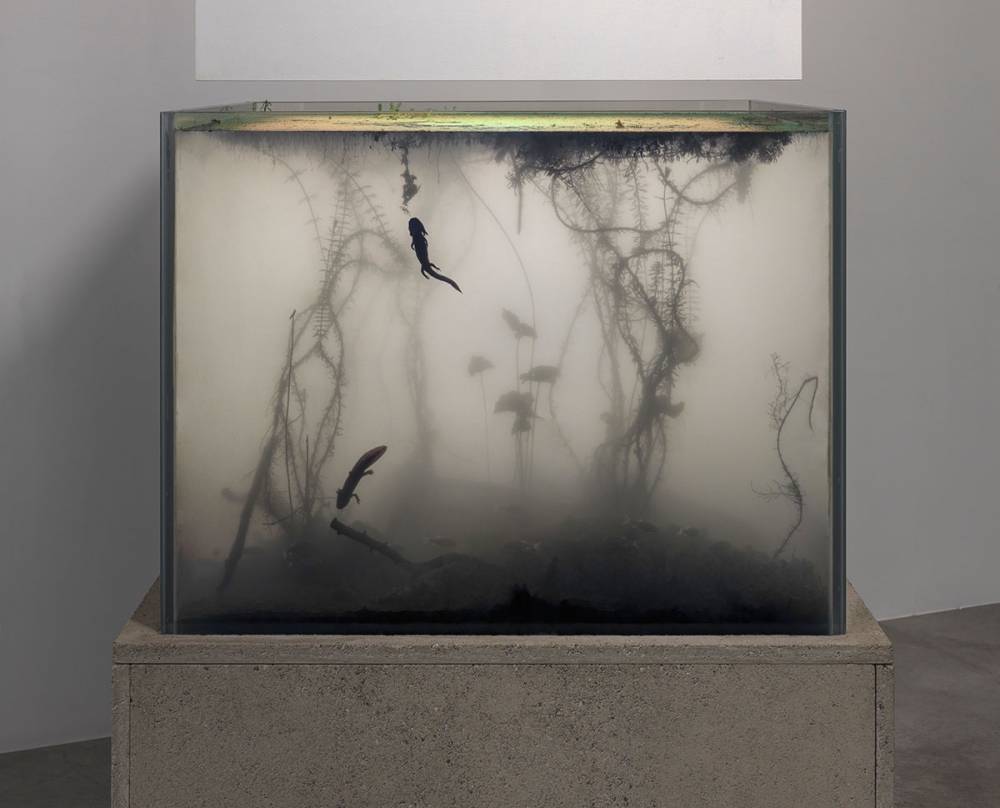

Philipp Timischl has built a practice on making artworks that behave less like static objects and more like characters in a play. Born in Austria in 1989 and now based in Paris, he works across painting, sculpture, video, photography, and text, collapsing distinctions between media to create installations that feel at once theatrical and oddly intimate. His pieces often stage encounters with power—whether tied to class, queerness, or the structures of the art world—while remaining disarmingly playful in tone.Timischl’s path into art was shaped by studies at the Städelschule in Frankfurt and the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, institutions known for producing artists eager to test the boundaries of medium. From early shows at Halle für Kunst Lüneburg (2016) and Secession in Vienna (2018), through to solo exhibitions at MGK Siegen (2023), Le Confort Moderne in Poitiers (2024), and the Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade (2025), he has steadily built a reputation for turning the exhibition itself into a stage.

Thursday, October 16, 2025

|

Alex Turgeon

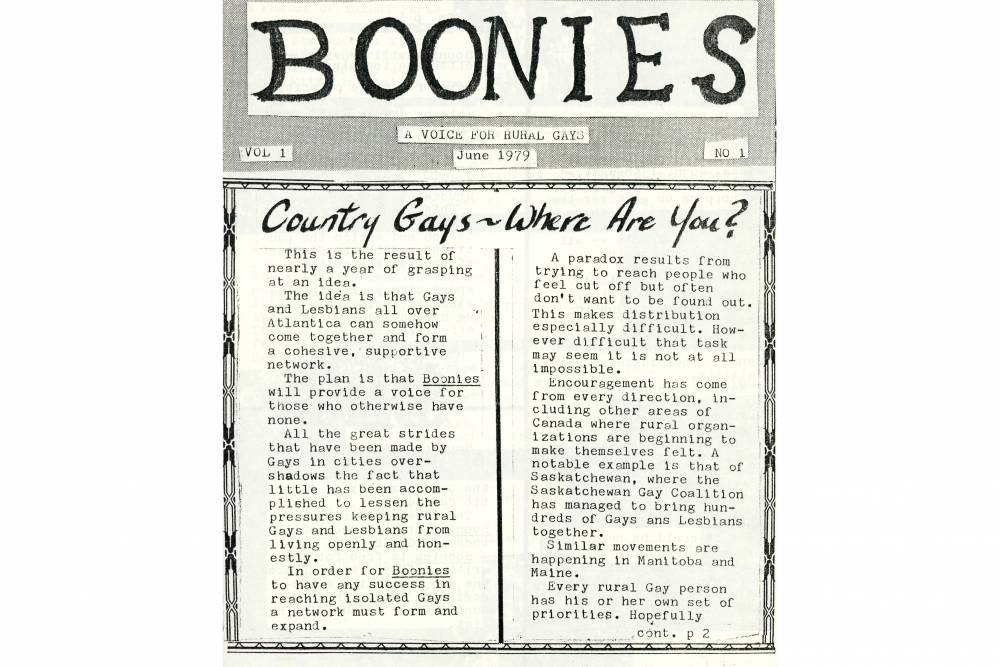

As urban environments evolve, becoming increasingly inhospitable to anti-normative practice, a once prevailing vision of escape regains resonance amongst the rigid contours of our cityscapes. This vision favours a desire to author one’s environment outside the far reaches of capitalism’s ever-expanding dexterity, predatory landlordism, and for-profit development, reigniting the dream to leave the pressures of city life behind. Existing alongside concurrent fascist flirtations, economic uncertainty, political unrest, humanitarian crises, colonial erasure, and genocide, the act of removal becomes a prevailing dream, albeit an ultimate luxury. For queer populations, home is often a fleeting idea and for those no longer captivated nor made safe by a queer home tied to the city, a belief in an alternative life is an essential tactic to persevere in the face of antagonism. Historically, this search for home has been manifested in the practices of independent queer publishing, which have been utilized to counter violent policies by offering an invitation to participate in radical new worlds. Printed matter has been wielded in diverse forms due its ability, and agility, to organize populations, invoke calls to action, establish networks and communal tethers, and provide essential resources for queer survival. Such incentives supplied the queer countercultural imagination with an antithesis to social and political hostility through back-to-the-land and alternative off-the-grid queer fantasies, shifting definitions away from a fully realized queer life being inherently cosmopolitan.

Tuesday, October 14, 2025

|

Christopher Lacroix

Whenever I see Alex Gibson’s work installed in a white cube I feel like I am seeing something naughty—something that wouldn’t be on pristine walls if everyone admitted they knew exactly what they were looking at. This is not to say that Gibson’s work is so heavily coded that a viewer needs to be deeply ingrained in a subculture to understand its signifiers. We know why the string of saliva off the pretty man’s face is so thick; we know what the streaming liquid aimed onto images of dogs is; we know how the silicone tail is affixed to the crawling man’s backside. All one needs is the slightest of dirty minds.

And yet, the affective pull of Gibson’s work isn’t solely its salacious content. The eroticism of the images—mostly appropriated from film, pornography, and archives, then recontextualized or rephotographed—is obscured by his material choices. High-gloss resin covers a grid of dingy-quality laser prints of low-resolution screen grabs, undoing the gallery lights’ function and creating a near impenetrable glare. Mirrors are used to produce depth where there isn’t any, refracting light into seemingly unnatural colour blocks. Gibson doesn’t make it easy for us to understand what we see.

Queerness exists in Gibson’s work both erotically and anti-normatively. The eroticism of Gibson’s work refuses the sexless respectability championed by gays and lesbians hoping to assimilate into the mainstream. And yet, it demonstrates a cogent understanding of how queerness stretches beyond non-hetero sex practices; that it is in opposition to broader structures of oppression.

Monday, October 6, 2025

|

Zinnia Naqvi

I recently met Shahana Rajani through various friends who had been trying to connect us after her relocation to Toronto from Karachi, Pakistan. Rajani is an artist whose practice stems from collaboration, pedagogy, and activism, and centres issues of climate justice within the local context of Karachi. Her collective Karachi LaJamia recently won the 2025 “Asia Arts Game Changer Award.” Rajani and her collaborator Zahra Malkani originally started their collective in response to censorship in the arts in Karachi, after a few violent attacks against artists and cultural workers who were speaking up for Indigenous rights. The duo felt that the community was generally complying with this call to silence, and out of frustration decided to create an alternate pedagogical experiment to share the history of activism in the Karachi art community.

What began as a series of workshops became a long-sustained collaboration rooted in land, placement, and belonging, and the collective work has also bled into Rajani’s solo practice. Her recent film and installation work, Four Acts of Recovery (2025) looks at the River Delta and fisherfolk communities who have moved with the river for generations.

Thursday, October 2, 2025

|

Aidan Chisholm

There is no such thing as a “neutral” public restroom. From tiles to stalls, even the most seemingly banal components of these spaces are, in fact, charged technologies of social regulation. The white ceramic grids that line so many restroom walls are not merely about cleanliness, but also control. And stalls—those flimsy off-the-ground enclosures—promise privacy while delivering surveillance against the backdrop of normative whiteness.

The public restroom as we know it in Canada and the United States is the living legacy of nineteenth-century sanitary reforms in Europe. When outbreaks of cholera and tuberculosis fueled anxieties of contamination, reformers championed architecture itself as a tool of hygiene. Sweeping infrastructures were enacted to control excrement, with elaborate networks of pipes constructed to carry waste out of sight (out of mind) with just a quick flush. The prototypical modern bathroom, as the writer Mark Wigley puts it, was “a healthy and health-giving interior whose whiteness countered, revealed, and accentuated the perceived darkness of interiors, dirt, soot, excrement, polluted water, vermin, the dirty skin of workers, poverty itself, and industrialization.” White surfaces became the standard of sanitary spaces, following the logic that such unadorned materials rendered filth easy to detect and eradicate, all to keep up a pristine facade. At the behest of architects like Le Corbusier, Adolf Loos, and Hermann Muthesius, whiteness itself was soon synonymous with hygiene as a moral construct, geared towards reinforcing established social hierarchies.

Monday, September 29, 2025

|

Filip Jakab

“When the sky was dark, I went down to my room to heat up a clothes hanger and press it against the back of my thigh until it went cold.” I read most of Natasha Stagg’s coming-of-age novel Grand Rapids (September 30, 2025) in the Flemish countryside on the 29th of June, with the sun burning my SPF-free skin, Marlboro Golds clouding my lungs, occasionally sipping “vodka, basil, cucumber & ice” gimlets. Stained by sweat or the gimlet’s thaw, some pages wound up saggy and soft. It occurred to me that, like the protagonist’s, my teenage years were long gone—my memories possibly thwarted, or tainted by my own interpretations—their patina forever scraped, they’ve become a cozy place of no return. “I watched skateboarders do tricks in front on railings. Their legs had no knees in their big Gumby pants. There was no outline of a bone to break. The sound of the wheels going over sidewalk seams was a ball scuttling over a roulette wheel but endless.” It’s 2001 and Tess, Stagg’s protagonist, describes the scenery in front of a hospital. She’s fifteen and works at Berrylawn Assisted Living, the fictional nursing home in Grand Rapids, Michigan. She has moved in with her aunt, uncle, and their kids, after her mom Sheila dies of cancer. She hates it here. Tess is three things: intoxicated, angsty, and sexually awake.

Thursday, September 25, 2025

|

Paige Greco

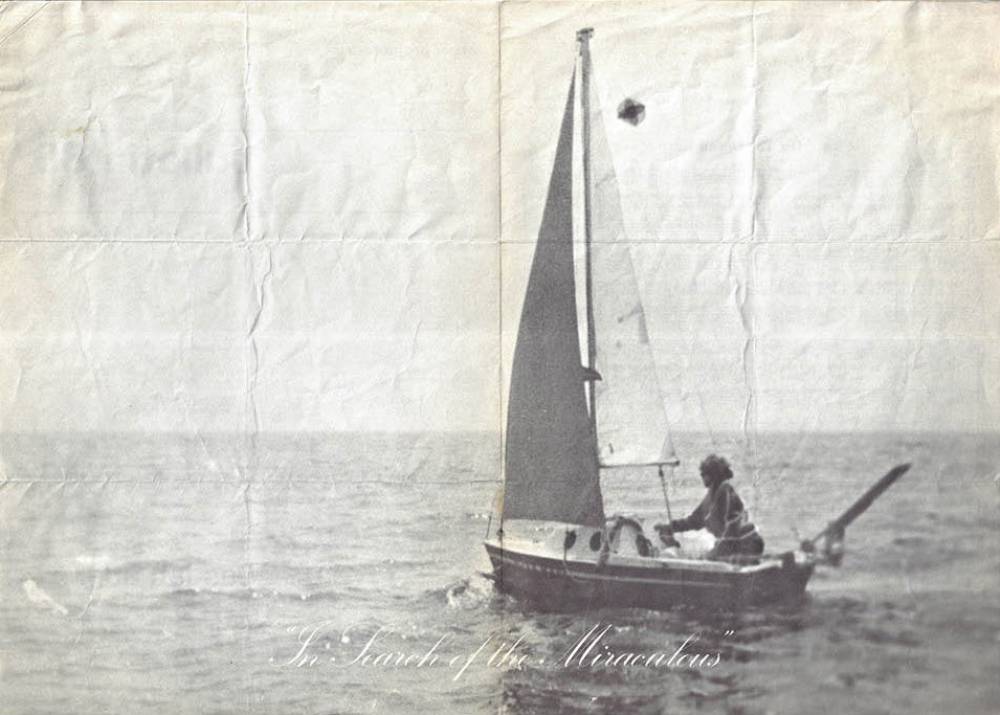

There, in the night—the quiet. Where the sea feels forever and exists independently of you.

Your boat moves softly beneath you. It feels too small, and you feel too fragile against the enormous dark.

In this moment, you are not someone’s anything.

You are only the moment before the fall.

Suspended, forever. Here, again.

You, brushing the corners of distance.

Your shape at the edge of a nerve.

Nothing.

It is Nothing but the Miraculous.

This is the image that returns to me often. A body, a boat, the forever. A gesture toward the infinite that ends in disappearance. Long before I knew what it meant to disappear, someone else had already done it. Not metaphorically. Entirely. This was the Dutch artist, Bas Jan Ader.

On July 9th, a half-century ago this year, for the second part in the triptych of his final work, In Search of the Miraculous, Bas Jan Ader attempted a solo transatlantic voyage in a small sailboat. He vanished.

Then we turned him into myth.

Monday, September 22, 2025

|

Alireza Bayat

Matthew Rankin can hardly fit into a single cinematic genre or a tagged box—and that’s exactly the point.

Rankin was born and raised in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and is currently based in Montreal. He was able to etch and carve a space of his own, first of all within the Canadian film scene, blending critical renditions of history and experimental collage with his personal idealistic ambitions that sometimes transcend to a poetic sphere.

He started his artistic journey as a teenager, spending time drawing, with an interest in the inherent values and concepts of human communication beyond the constraints and absurdities of the established structures. While doing so, he was making friends beyond linguistic and cultural borderlines—two evident elements of his oeuvre to this day. This helped him to have a broad understanding of world cinema and a varied cinematic lexicon that as he states contributed to his cinematic “being.”

Thursday, September 18, 2025

|

Fatima Aamir

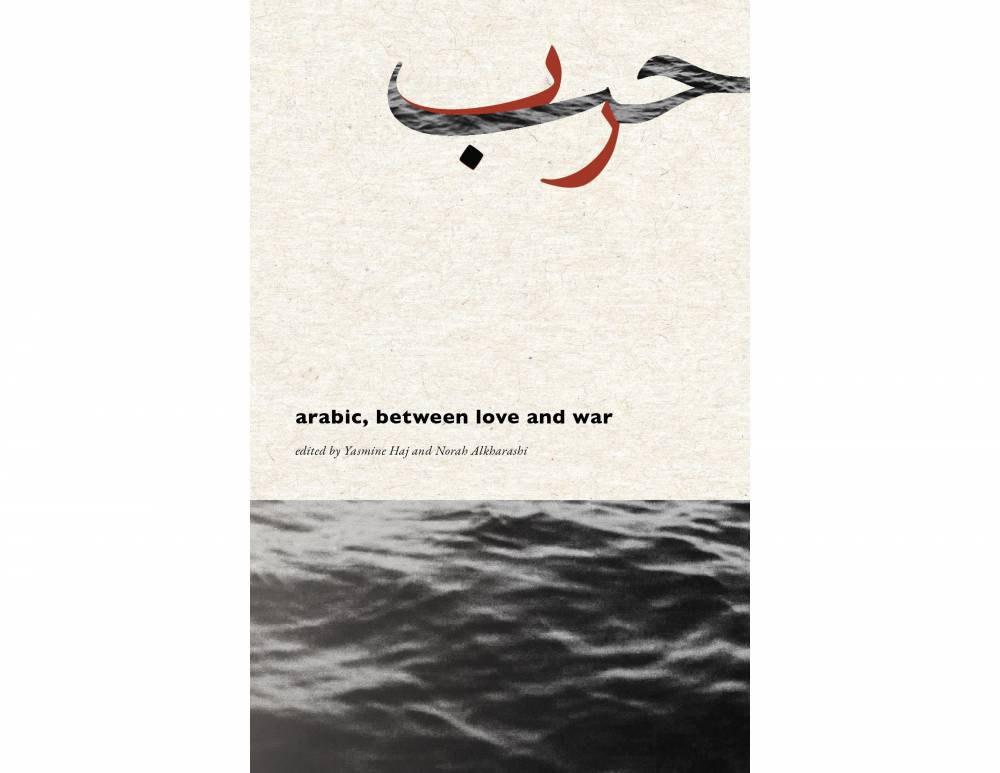

Arabic, between Love and War is a book of Arabic poems side by side with their English translations that resists the pitfall of "humanization." It is part of trace press' process-based publication series, where each publication arises from a number of creative workshops. This collection in particular arose from workshops held between 2022 and 2023, facilitated by the editors Norah Alkharrashi and Yasmine Haj.

Literary translation and "humanization"

The publication series explores the challenges of writing and literary translation. Literary translation raises a number of troubling ethical questions in general, but such questions are especially salient when dealing with a language/people and geopolitical context laden with existing presumptions and politically-charged narratives.

In "Between Impossibility and Necessity," an opening section of the text, editor Norah Alkharrashi writes that the art of literary translation is both impossible and necessary. Alkharrashi writes of the difficulties of translation, especially of poetic translation, "which, being among the most refined and expressive of literary forms, is expected to have myriad and complex nuances." Scholars of comparative literature, who engage with literary texts across cultural, geographical, and linguistic contexts, have long grappled with the limitations of literary translation. Such awareness has been enriched by the recent growth of critical translation studies, itself shaped by decolonial, antiracist, and feminist thought.

Monday, September 15, 2025

|

Filip Jakab

The first time I ever heard Dancing on My Own from Robyn was a month or so after it was officially released in 2010. I was 18, visiting my grandmother in bleak Galway, Ireland. I remember looping the song blasting from YouTube on my shitty Android phone back then, over and over again until I got over it the very same day. I had no clue that years later, I’d stumble upon a book borrowing the same eponymous title as Robyn’s song. "If gays don’t make babies when we have sex what do we make?… Just the idea of ourselves, over and over?" Simon Wu ponders in his debut, Dancing on My Own: Essays on Art, Collectivity and Joy, published by Harper Collins in 2024. A writer and artist, a millennial like myself, Wu, who is currently enrolled in the PhD program in History of Art at Yale, told me during our Zoom interview that he “prefers a colloquial way of expressing a really high theoretical thought.”

Wednesday, September 10, 2025

|

Kaya Noteboom

I want to stop thinking about myself. In fact, I wish I could lose my “self” completely. Not for lack of will to live, though. Quite the opposite. I sense with greater frequency that my “self” gets in the way of living, or, is the focus of an inhospitable pressure. It was an unexpected realization, in part because, at present, the need for self-actualization—the pinnacle in Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs”—has become an effigy of Western pop-psychology. With a puzzling degree of certainty, we generally seem to believe in an “authentic self.” It’s this version of the self—not the one you presently are—that’s capable of expressing and utilizing its full creative potential. This actualized form presides like a spectre over our lives, omnipresent since birth, and perpetually out of reach. Art and politics function as modes of symbolic representation within this schema. They present a multitude of techniques to make the self visible to one’s self and to others. These mediums give the self a tangible form and aid in its continual management. The most common notions of selfhood depend on the legibility that art and politics provide, enabling a sense of security in an unstable world. Today, as people’s ability to meet Maslow’s lower needs (food, shelter, and loving connection) are strained by the pressures of late-capitalism, an inversion has occurred. The hierarchy has flipped. Somehow—though I have my suspicions—self-actualization has become the skeleton key to basic survival.

Monday, September 8, 2025

|

Filit Sureki

Ghayath Almadhoun, a Palestinian-Syrian poet born in Damascus in 1979, is a singular voice in contemporary Arabic poetry, crafting works that navigate the intersections of exile, trauma, and resistance with unflinching clarity and surreal intensity. Born in the Yarmouk refugee camp, a historic center of Palestinian diaspora in Syria, Almadhoun fled the Syrian dictatorship in 2008, three years before the Syrian Revolution, eventually settling in Sweden and later dividing his time between Stockholm and Berlin. His statelessness—what he calls being “exiled from exile”—informs a poetic practice that defies conventional forms and national boundaries. Writing primarily in Arabic, often in collaboration with translators like Catherine Cobham and Marie Silkeberg, Almadhoun creates poetry that resonates globally, blending visceral imagery with sharp critiques of power, war, and displacement.

Thursday, September 4, 2025

|

Ada Kalu

Rarely is the camera used to protect. More often it serves to capture, expose, and surveil. Deborah-Joyce Holman’s Close-Up stands in defiance of this, offering an alternative to this use of the lens. Unburdened by distraction, the film is a quiet loop of carefully framed shots following actress Tia Bannon around an apartment. We focus solely on her face, shadowing the mundanity of her actions—filling a kettle, eating fruit, lying down—entranced by her preoccupation. There is no grand narrative, no sound beyond her movements, and yet, we are left wanting more. What is she doing? What happens next? The slow pacing and tight framing bear the weight of expectation. Surely, such close contact must satisfy our curiosity and bend to the whims of our desires. But even her absence—a two-minute window—is controlled. Waiting like expectant guests, we are left looking around. Presented with an opportunity to learn more about Bannon, her disappearance triggers the camera to shield once again, viewing her space through paced and lingering shots. These are the set terms for access. This deliberate refusal to accommodate or offer clarity is central to Holman’s practice. Close-Up refuses to placate, instead offering a tension and a kind of aliveness rooted in intimacy and resistance.

Tuesday, September 2, 2025

|

Nicolas Vamvouklis

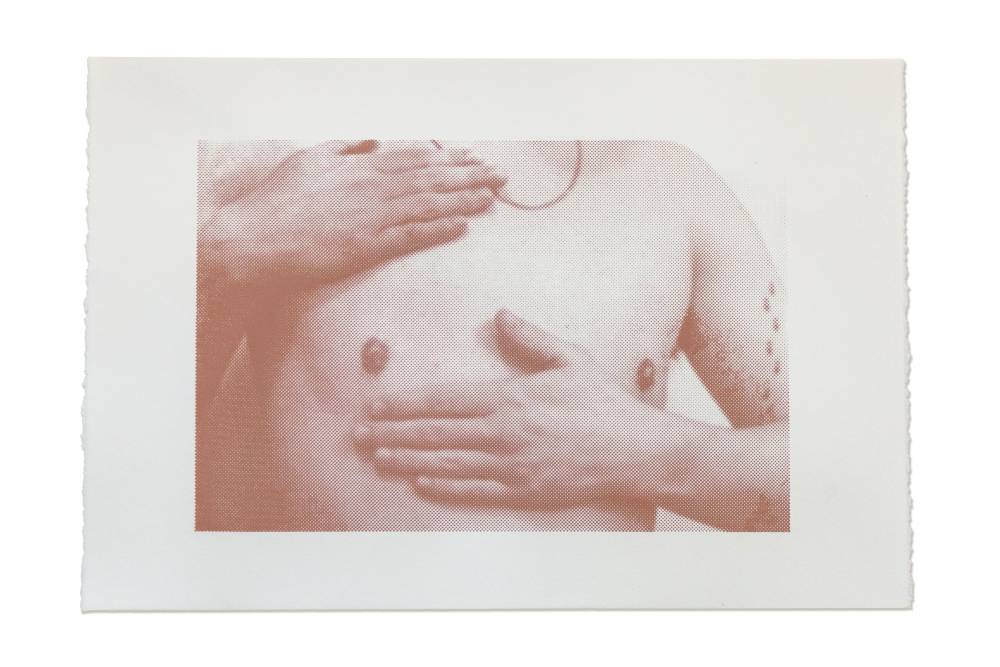

Rebecca Ackroyd’s sculptural and pictorial worlds feel at once familiar and estranged. Dreamlike yet grounded in physicality, her practice spans drawing, sculpture, installation, and photography—often weaving together cast body parts, found objects, and domestic remnants into unsettling tableaux. Her figures, neither wholly present nor absent, evoke a surreal sense of interiority, vulnerability, and transformation. In her work, the body becomes both a site and a memory device—glitching, fragmented, and imbued with narratives that resist resolution. Born in 1987 in Cheltenham, UK, and now based between London and Berlin, Ackroyd studied at the Byam Shaw School of Art and completed her postgraduate diploma at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Over the past decade, she has steadily built a compelling body of work that attracts international attention.

Tuesday, August 26, 2025

|

Gabrielle Willms

Before officially meeting Séamus Gallagher, I knew who they were, and every now and then, I would pass them walking through downtown Winnipeg. On more than one occasion, they were wearing an excellent yellow suit. And each time, this dash of colour against the dull beige and brown facades of Portage Ave shifted the tenor of my day. A little jolt of visual pleasure, in a city whose harsh climes reduce most of us to down-filled neutrals, is always welcome. Over time, it also struck me as a bit irreverent or even challenging, like a little ripple in our staid visual language, or an invitation, maybe, to play with our own public performances. As I’ve learned more about Gallagher’s practice, it’s become clear that they excel at pulling their audience in immediately, and then letting the critical questions their work poses simmer over time. Gallagher’s work is typically gorgeous, in the sense that it’s vivid and saturated, a delicious, over-rich eye candy. It’s also gaudy and strange.

Wednesday, August 20, 2025

|

Doreen Nicoll

David Garneau first came to my attention when someone shared his 2013 painting Not to Confuse Politeness with Agreement on Twitter. The painting depicts Stoney Nakoda Chief Ubi-thka Lyodage (1874 – 1970) facing and shaking hands with an unknown young RCMP officer. Above the officer’s head is a square. Above the chief is a circle. I thought it brilliantly represented the challenge of (re)conciliation. So when I was invited to review his book Dark Chapters: Reading The Still Lives of David Garneau, I leapt at the opportunity. Garneau is a painter, writer, curator, and professor who currently creates metaphorical still life paintings that express Indigenous issues through common and uncommon objects.

Monday, August 18, 2025

|

Abby Maxwell

It all started when I was chipping frozen milk flecks with the wrong end of the spoon into my coffee at the cabin. I left the carton outside overnight, resting in a snowbank. The cold had lured us out of bed before dawn to huddle around the wood stove. It was the morning after we harvested the rabbit from a snare fixed to a spruce branch—now a friend sat with her, dissecting her body into parts, her blood pooling onto the cardboard splayed out on the cold floor.

The icy milk chips thawed upon impact with the coffee, failing to incorporate and, instead, floating as a speckled mass of oily whiteness. It produced a reaction in the others—the visceral sort; disgust, like my own flinching, looking into the hare’s jet-black eyes or watching this friend’s hands peeling her fur off in one distorted piece. Two snow-white forms, in from the cold, on their way to feeding us.

Monday, August 11, 2025

|

Kaya Noteboom

The nameless narrator of Lara Mimosa Montes’s new book, The Time of the Novel (Wendy’s Subway, 2025), makes a plain confession. “I was over being a person, one with a social security number, a natal chart, an undecided future, and a passport.” It’s an absurd thing to desire, and completely relatable. It should seem absurd that so much of what distinguishes a person as such is fundamentally impersonal: someone’s birth time and place, a set of randomized numbers, government-issued papers—stuff that’s all too easy to forget or misplace. Yet, the stakes of having or not having these materials couldn’t be higher as people in the US are being forcibly taken from their homes, their places of work, and off the streets to be deported, detained, and subjected to dehumanizing violence. What The Time of the Novel’s narrator attests to is that life as a person, vital items in tow, isn’t all that livable either.

Friday, August 8, 2025

|

Antony Zelenka

At the back of the Manulife Centre, a luxury shopping mall along the “Mink Mile” in downtown Toronto, in an unassuming corridor of the movie theatre, is a piece of décor that is totally unremarkable for any corporate lobby, yet surprising when given a moment of pause: a saltwater fish tank, featuring a live coral reef. The fact that this and other publicly displayed aquaria have not yet been replaced with flat screens playing a 10-hour YouTube video on loop, “Best 4K Aquarium for Relaxation and Calm Sleep Music UHD,” stands out among today’s ornamental impulses, especially because of the murky challenge of keeping an aquarium’s micro-cosmos in delicate equilibrium (I say so, sadly, from experience). Aquarium fish remain ubiquitous in day-to-day life and are found in settings ranging from restaurant interiors, to tourist attractions, and medical waiting rooms. By sheer numbers, they are among the world’s most popular pets and comprise a multibillion-dollar industry, per a study of the global pet fish trade.

Tuesday, August 5, 2025

|

Michael Anthony Hall

When I first encountered Camila Arroyo’s work through Soldaderas nearly four years ago, I was immediately struck by her ability to command space and express unspoken language in her movements. The short film for the fashion brand Sabrina Ol captures Arroyo as she navigates Mexico City’s streets. The film feels less like a performance and more like an intimate conversation with the environment. Where movement, for her, was a private language that spoke to everyone, a pulse threading the soul to the surface of the world.

From the very start of our conversations, it became clear that Arroyo’s journey into dance was anything but conventional. “I don’t remember a time in my life without movement,” she shared. Her exploration of dance has always been driven by instinct and curiosity, pushing her to challenge norms and carve out her own path. From her initial resistance to traditional dance classes to her transformation through her time at the National Ballet School in La Habana, Cuba, dance became more than an art form—it became a lifelong practice, a devotion.

Wednesday, July 30, 2025

|

Shiv Kotecha

In the dim blue hue of an office light, we see a pair of eyes gloss over a floor strewn with dead, bloodied bodies. The eyes shudder and look out somewhere, into the middle distance; not at the walls of the conference room that enclose them, not directly at the glow of a computer screen. Below, a pair of hands continues to maniacally hit a keyboard. These furtive movements belong to Claire, played by the inimitable Kayije Kagame, the protagonist of filmmaker and artist Valentin Noujaïm’s chilling 2024 short film, 'To Exist Under Permanent Suspicion' (2024), who we watch, sit alone, but not alone, become like stone, or statuary, in her dark, corporate chamber. What does she see?

For nearly a decade, Valentin Noujaïm, who grew up in France as the child of Lebanese and Egyptian emigres, has been making films about the erasure of peoples and histories by the construct of empire and the bleak façades of “progress” erected in their stead. Le Défense, the looming business district to the west of Paris, built on razed shantytowns, gives the name to a trilogy of short films by Noujaïm (2022-25), each of which fuses documentary technique with mythic narrative to mine and undermine the monument’s rotting foundations.

Thursday, July 17, 2025

|

Hannah Azar Strauss

As I leave artist Lorna Bauer’s house after my visit to her home studio, our third meeting, she gives me a hug and wishes me luck on an upcoming move. We make plans for a drink on her back porch, “once things start to bloom.” Walking away I make notes on my phone about the visit. Patricia’s garden upstate. Daffodils, hydrangea, magnolia. Grouse like a dirt bike. Adair’s drawings. Pollinators. States of transformation.

Like glass in its molten state. Like the latent image on film as developer meets fixer meets water meets heat. Like a flowering tree in April in Montréal.

It's been only a few weeks since we first met. Although I’ve been following Bauer’s work for some time and we both live in Montréal, our paths hadn’t crossed before this profile. We meet in March, on what was the warmest day of the year so far—though it’s since been surpassed many times, thank god. An ugly, garbage-decked, rhapsodic Tuesday in late winter. I walk across a few neighbourhoods from my home to meet Bauer at one of Montréal’s big studio buildings, working up a seasonally-unlikely sweat, caught up in an impression of being passed on all sides by runners made quick by their freedom from specialty winter gear.

Monday, July 14, 2025

|

Danny King

The Canadian writer-director Naomi Jaye’s work frequently probes eccentric characters who pursue a peculiar agenda of routinized loneliness. Her first short, the madcap A Dozen for Lulu (2002), uses a stylized soundtrack (blaring alarm clocks, squeaky chairs) and an agile camera to depict two oddballs who share an enthusiasm for sprinkled donuts: a cheery, rollerblade-wearing ballerina who works at a hardware store, and a man in a fur cap who, with academic precision, nails the pastries to his workshop walls. Two of Jaye’s subsequent shorts, both starring the excellent Adrian Griffin, provide more subdued portraits of solitary souls. In The Raindrop Effect (2003), Griffin’s character, outfitted in a frumpy robe and brown loafers, endures the doldrums in his empty home—until he begins to forge a restorative relationship with the rainwater collecting in his leafy backyard. Arrivals (2007), also a single-location piece, deals with a man who perpetually hangs around an airport waiting area, looking on in hushed awe at the hordes of travelers reuniting. Arrivals leaves the reasons for the man’s loitering unstated, but The Raindrop Effect includes a touch more context for the despair. The man in the robe rummages through old crates bearing mementos, toys, and photos of a family at Christmas time. He dons a motorcycle helmet and stares at himself in the mirror—perhaps revisiting a particularly important memory.

Wednesday, July 9, 2025

|

Shiv Kotecha

There is no vacancy in this world, no void, no vacuum. This is one thing I learn when I encounter the artwork and read the essays by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa. Every moment in life is durational, and every image we happen to see within it, an unfolding reel through which the social world is rehearsed, or composed, or erased, or betrayed, or determined. What do we desire from images? Whose lives are risked? In his installations and exhibitions, as in his precise, angular writing about art and photography, Wolukau-Wanambwa guides his viewers and readers into the darkly layered logics of idolatry, difficulty, and exposure that undergird photography’s capacity to represent black and gendered bodies, and the violent regimes of white supremacy and patriarchy that produce them.

I first saw Wolukau-Wanambwa’s work in person as part of the 2021 iteration of Greater New York at MoMA’s PS1, where a suite of images and objects were displayed against an entirely black background. Vivisecting the space was AMWMA (2021), a free-standing wall on either side of which was hung two, nearly identical life-size photos of the actor Anna May Wong.

"like a bell, or tuning fork”: in conversation with poet and interdisciplinary artist Danielle Vogel

Monday, July 7, 2025

|

Nasrin Himada

In this conversation, I speak with Danielle Vogel—poet, interdisciplinary artist, practicing herbalist, ceremonialist, and professor at Wesleyan University. Over the past 20 years, Vogel has written and published four poetry books that engage embodied poetics, feminist ecologies, somatics and ceremony. Our focus here is her most recent work, A Library of Light, published in 2024, which I first read in 2025, during one of the most intense winters in Montreal. It arrived at a time when I was seeking something I couldn’t quite name.

I was so moved by the way Vogel writes through grief—not around it, not away from it, but through it. For many of us diasporic Palestinians, as we continue to witness the genocide of our people, the grief is more than unbearable—grief is more than what language can bear. I was searching for a way to stay connected to that grief that didn’t close me off—a way that felt like an opening, something grounded, more integrated with what is.

Monday, June 30, 2025

|

Kate Nugent

Throughout the Balkans and Southeastern Europe there is a popular folktale that describes the tragic, sacrificial immurement of a woman to ensure the successful construction of a building. From Albania to Georgia, around 700 variations of the myth exist, including “The Bridge of Arta” in Greece, “The Building of Skadar” in Serbia, “Clement Mason” in Hungary, and “Master Builder Manole” in Romania. Though the constructions in these tales vary from bridges, to fortresses, to monasteries, they share the same basic narrative: a man sacrifices a woman against her will in order to create the foundation upon which a structure can be built. Romanian-born artist and filmmaker monica maria moraru recently explored the Master Builder Manole myth in her exhibition The Foundation Pit. In the exhibition, moraru not only revisits the myth and its cultural influence but also considers the intertextual links between the sacrifice-for-construction myth and the literary work from which the exhibition derived its title: Soviet writer Andrei Platonov’s novel The Foundation Pit.

Wednesday, June 11, 2025

|

AO Roberts

I met multidisciplinary artist ESO MALFLOR in Minneapolis while I was an artist in residence at Dreamsong Gallery in 2024. When we met, they told me about their land-based practice and recent experiments with clay. I also had recently started working with clay, making small ceramic sculptures to 3D-scan into a virtual world, while MALFLOR had been using clay in drawing and performance. They described their performance Equilibria (2023), in which they covered themself and the performance space with a full tonne of clay. Accompanied by violinists Arlo Sombor and Creeping Charlie, they made micro-movements over an hour while the clay slowly flaked off. Intrigued to learn more about their practice, I visited their studio tucked above a rummage shop on an early spring day in March.

At the time, MALFLOR was preparing for their show, The Earth is a Body in Transition, at HAIR + NAILS. Their small workspace was packed with scavenged materials, burnt remains of buildings, carved charcoal, and conglomerations of bones and nails.

Wednesday, June 4, 2025

|

Hannah Strauss

Almost twenty years since being introduced to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, a few of its pages still regularly come to mind. One panel in particular, in which a face is progressively whittled down to its simplest graphic form, two dots and a line, has really stuck with me. The narrator asks, “WHAT IS THE SECRET OF THE ICON WE CALL – THE CARTOON?” And in the next panel, “WHY - ARE - WE - SO - INVOLVED?” McCloud poses a question to the reader about why this brutally diminished form is still so “acceptable” to us – why, rather than estranging, it can open up a space for identification more immediate and reliable than one highly realized.

For those more widely read in the genre than I am, it might feel a bit reductive to open an interview with Walter Scott, the Kahnawà:ke-born, Tiohtià:ke (Montréal)-based interdisciplinary artist and author of the much-loved Wendy comics, with reference to McCloud’s classic introduction. But I thought about these panels while preparing to interview Scott, not just because he makes comics, but because his work foregrounds the genuinely mysterious capacity of caricature to both reduce and elaborate character. Scott’s figures and their attendant objects (or his objects and their attendant figures) capture simple being – for instance, the plainly apparent experience of misery, that infinitely non-universal universal. Simultaneously, they offer us characters nobody could fail to recognize as vitally specific, differentiated, subtly or not, by their particular features. I mean class, race, gender, but also eyebrows, shoes, or types of ambition.

Tuesday, May 20, 2025

|

Nasrin Himada

The conversation that follows below began in the fall of 2024, shortly after I saw Razan AlSalah’s film 'A Stone’s Throw' at Prismatic Ground, an annual festival dedicated to expanded documentary and avant-garde film, curated and run by Inney Prakash. AlSalah is a filmmaker and teacher based in Montreal. What I am drawn to with AlSalah’s work is her ability to pull us into an image, or have the image spatialize our cinematic experience in a way that feels tactile, immersive, moving, and expansive. Her work engages the material implications of image-making, particularly through the layering of multiple narratives and the branching pathways that gesture toward a relational movement of diasporic living. At its core, there is an anti-colonial vision—one that insists on the resurgence of life on Indigenous lands while rupturing the colonial image. Her films often operate as “ghostly trespasses,” bypassing the seemingly fortified map of colonial borders. For AlSalah, filmmaking is a form of collective memory-making, unfolding in relation with others, with place, and with the unknown.

Wednesday, May 14, 2025

|

Lindsay Inglis

Over the past few years, artmaking became an extension of parenting for Dominique Rey. She created matching costumes for her and her children, Madeleine and Auguste Coar, and would set up a camera for a period of what she called ‘intentional play.’ In doing so, Rey captured images honouring the relationship between mother and child.

I first met Rey at her studio in Point Douglas, where she invited me over for tea after I reached out about this article. After months of researching her work, I was running late and worried I was making a bad first impression. She didn’t mind though and spoke generously about her practice and the then upcoming solo exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, Motherground. She showed me the photos included in her exhibition as well as the gallery maquette with the exhibition layout, and there was also prototype of one of the sculptures in the corner of her studio. Rey had piles of art books on motherhood, on various photographic projects surrounding motherhood and on what it meant to be an artist and mother. One of the books was Home Truths: Photography and Motherhood, edited by Susan Bright, who Rey was excited to share had contributed an essay to Motherground’s catalogue.