A journal for storytelling, arguments, and discovery through tangential conversations.

Wednesday, January 28, 2026

|

Nic Wilson

I once heard a biblical scholar say that the Bible is much more like a library than it is a single book. Its polyphony is the result of many writers and translators creating branching paths along interlocking bands of narrative, guidelines, genealogies, songs, laws, histories and parables. It represents the shifting textures of religious thought as they have been shaped by time and circumstance. It is a raft of contradictions and tangents. It is a compendium of drift and change. The codex currently distributed by the Gideons is constituted as much by what has been edited out or lost as much as it is by what remains on the page. It is a well used library.

Unlike the narrative mess of the Bible, Western views of the past tend to assume history as a comprehensible, narratively consistent whole. In this view of knowledge, remainders are rounded off and doubts are often squashed when they disrupt a thesis or are relegated to endnotes. In the work of Calgary-based artist Lyndl Hall, ideas, shapes, and histories have scattershot points of articulation which often run counter to the assumed wholeness of history. With enough data points one can imagine a whole— but this view always comes with the need to squint or view from a distance.

Wednesday, October 22, 2025

|

Nic Wilson

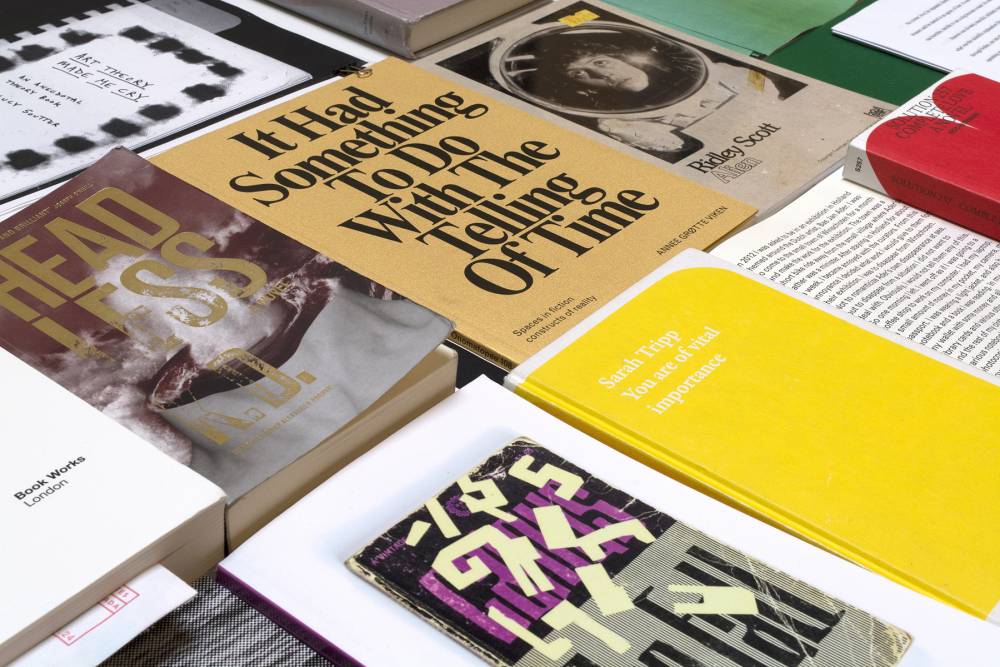

Over the last decade, I’ve had many conversations with peers about why artists’ publishing seems to remain so niche, especially in the landscape of Canadian contemporary art. It’s rare to see artists’ books in gallery settings and rarer still to get access to museum libraries. It’s almost unthinkable that an institution might offer a free book as part of its programming. These are by no means impossibilities, but they remain isolated experiences amid the overwhelming majority of exhibitions which tend toward more traditional art objects, performance, and video. Throughout my practice, questions of ontology in art-making have emerged and receded, but the question of where books belong in an arts ecosystem continues to spark contemplation and confusion for me.

Part of this confusion stems from the fuzzy task of definition—one that feels more like assembling a raft of exceptions rather than a list of declarations. In my experience, the artist’s book can be clumsily analogized thusly: any type of book in the visual arts can be an artist’s book but not all books in the visual arts are artist’s books. They can be published in conversation with other works but they are usually not documents of exhibitions; they are works in and of themselves (as much as an artwork can ever be considered a discrete unit). There is no prescribed way of producing an artist’s book. They can be singular, handmade objects or mass produced in ways that make them almost indistinguishable from other commercially produced books. They can be made in traditional printmaking studios or at a municipal library with laser printers, scissors, and tape.

Wednesday, August 28, 2024

|

Nic Wilson

I know a lot of things about Audie Murray. I’m not sure how much of it is relevant to her art practice. I know her brother works on trucks in his spare time and I know what high school she went to. She has told me about her dreams. I know her child’s name and how she takes her coffee. I know how her kitchen is arranged and what is in the fridge: Babybel cheese, firm tofu, and at least three varieties of berries. She told me that when she is depressed and the idea of cooking food is unimaginable, she eats cubes of tofu with nutritional yeast. It is also one of her son’s favourite things to have for lunch. I often wonder how much I can know about someone’s art based on being friends with them. Murray grew up on Treaty Four land in oskana kâ-asastêki (also known as Regina, SK). She is a Contemporary Cree-Métis artist with community connections in Lebret and Meadow Lake.

Tuesday, September 5, 2023

|

Nic Wilson

Breath feels like a person’s most immediate form of need. Water and food can wait and intervals between pissing or shitting can be measured in hours but breath is so essential it hangs at the periphery of consciousness. The conscious mind can dictate these intermittent needs. You can forget to eat and even choose to starve but breath is much more slippery. If you forget about it you still maintain a breath pattern but if you start to think about it you can fool yourself into believing you might never take another unconscious breath. Unlike blood flow or digestion, which one has little to no conscious control over, breath can be held strategically (while swimming in water or escaping a house fire) or become a tool. You blow out the scented candle the way some distant ancestor blew pigment onto a cave wall to capture the negative space of their hand. In the Bible, God creates Adam out of dust and breathes life into him through his nostrils. Breath has been used as an essential signifier of human life itself. Along with keeping us alive, it connects us to the lungs of people around us; a sometimes unbearable intimacy especially after 2020. That year, unlike many others I have known, the air became charged—politically, emotionally, economically, environmentally—like the gasses in Earth’s upper atmosphere when the Sun’s radiation shoots through it, triggering the glow of the aurora.