Portrait by Yuula Benivolski

Amy Ching-Yan Lam and I look over the menus at a packed cha chaan teng (Hong Kong-style diner) in Markham, a suburb of Toronto. In the background are sounds of clattering dishware and Cantonese conversations. People are crowded into the small entryway as they eagerly await a table, glancing at diners who might be finishing up their meals. The energy in here is frenetic, but not unpleasant. Lam speaks Cantonese. I don’t. In this setting, the language conveys ease and maybe belonging, but is not required for ordering our midday meal. Descriptions of the dishes are written in Traditional Chinese (as it would be in Hong Kong) and in English (as it sometimes would be in the former British colony). Customers are guided by numbered pictures. The plastic-coated menu presents us with glossy photos of classics like pineapple bun sandwiches, baked meat and cheese casseroles served over rice, and instant noodles with a list of add-ins—the original fusion foods.

Amy Ching-Yan Lam is a mid-career visual artist and, more recently, a writer of books. She began her visual art practice collaborating with Jon Pham McCurley as the two-person collective Life of a Craphead (LOAC). Their projects included the exhibition Life of a Craphead Fifty-Year Retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario (2013), the feature-length satire film Bugs (2016) and the public art project King Edward VII Equestrian Statue Floating Down the Don River (2017). Working solo, Lam continues to make artworks that approach social issues and communal and personal histories with wry humour. Now dedicating more time to writing, Lam recently published her first book titled Baby Book (Brick Books, 2023). Though categorized as poetry, Baby Book reads to me like a series of brief, tender, vulnerable and sometimes plainly factual stories on formation, family, power, and life told in a way that makes oddness feel familiar. In both her writing and visual art, absurdity and emotional truth work in tandem, each revealing something of the other. It was enriching to speak to Lam about her work across disciplines; how her early experiences as a writer led to her entry into contemporary art and the important place that collaboration continues to have in her practice.

I first became acquainted with Lam when she was still part of the artist duo LOAC with McCurley. My initial encounter with their work was perplexing. I entered the Jon Pham McCurley exhibition Double Double Land Land (2009) at Gallery TPW without knowing what to expect. Lam was one of the project’s many collaborators. The two were on-hand giving visitors a run-down of the installation. As I recall it, it was a digressive tour, launched without a lead up, jumping from work to work. I’ll admit that I left feeling unsettled, not understanding what I had just experienced. Looking back at that exhibition on TPW’s website, I realized my encounter with the duo was via one of their “performance-demonstrations.” My discomfort didn’t deter me from continuing to try to make sense of their practice by attending an episode of “Doored,” their variety show that ran from 2012 to 2017 in the Kensington Market venue, Double Double Land. It was unclear whether the performers intended it to be comedic or not.

When I was trying to get started on this profile, Lam and I repeatedly attempted to get together, beginning in the summer of 2023. We had the intention of walking and talking in nature; we both enjoy hikes. It became fall and we considered a visit to an alpaca farm. Abandoning these ideas, I suggested a Ploughing Match and Rural Expo. Both could be novel. Over this period of time, Lam was traveling frequently, promoting Baby Book, and at the same time, presenting other projects and working on collaborations. Scheduling a meet-up became a lot of effort, the way scheduling in Toronto often does. Lam eventually suggested lunch at the cha chaan teng. I agreed; I’m always up for a drive out of the city. With Lam in the passenger seat, we dialed through radio stations trying to arrive at something worth listening to while looking out at the urban-suburban landscape. Along the route, we talked in that way that long drives are conducive to, with pauses for thought punctuating our dialogue.

I thought about how and why we came to be in each other’s orbit. Without previously having named it, I now recognize that we share the experience of being Chinese-Canadian women navigating similar professional contexts and realities. To some, this may be the presumed basis of relationship making, but such commonalities are not always enough to draw people together. Instead, for me, Lam’s navigation of her own identity in her writing and visual art reflects to me things I’ve felt in my gut but hadn’t articulated myself. Relationships like this are crystalizing.

Toronto (where me, Lam, and McCurley all live), is small and I became friendly with the two over the late 2010s. I co-curated (with cheyanne turions) LOAC’s exhibition Entertaining Every Second at AKA Artist Run in Saskatoon (2017). Although Lam had already been writing, mostly privately, her writing showed up in a new way in Entertaining Every Second. Something that we have both recognized as a turn: “I wrote the text about The Quiet American. I think that’s when the writing practice really started. I enjoyed it and that show was a pivotal moment in terms of the kind of work we were making and our collaboration.” The full title of the work Lam is referring to is The Quiet American But Only The Parts Where the White Man Main Character Tells the Asian Woman To Do Stuff for Him. The work consisted of white text on four, green panels hung on the wall. The text was simultaneously literary critique–a takedown of racist white misogyny–and a meditation on the weight of the lived experience of that oppression. The English novelist Graham Greene’s The Quiet American is set in Vietnam during the breakdown of French colonialism and early in the US war in Vietnam. Greene’s development of the character Phuong never moved beyond that of the beautiful Vietnamese girlfriend seeking security. In Lam’s work, Phuong, and women like her and me, are consequential. We are real, representing ourselves. We have agency. We are creators. We can be our own narrators and main characters if we choose to be.

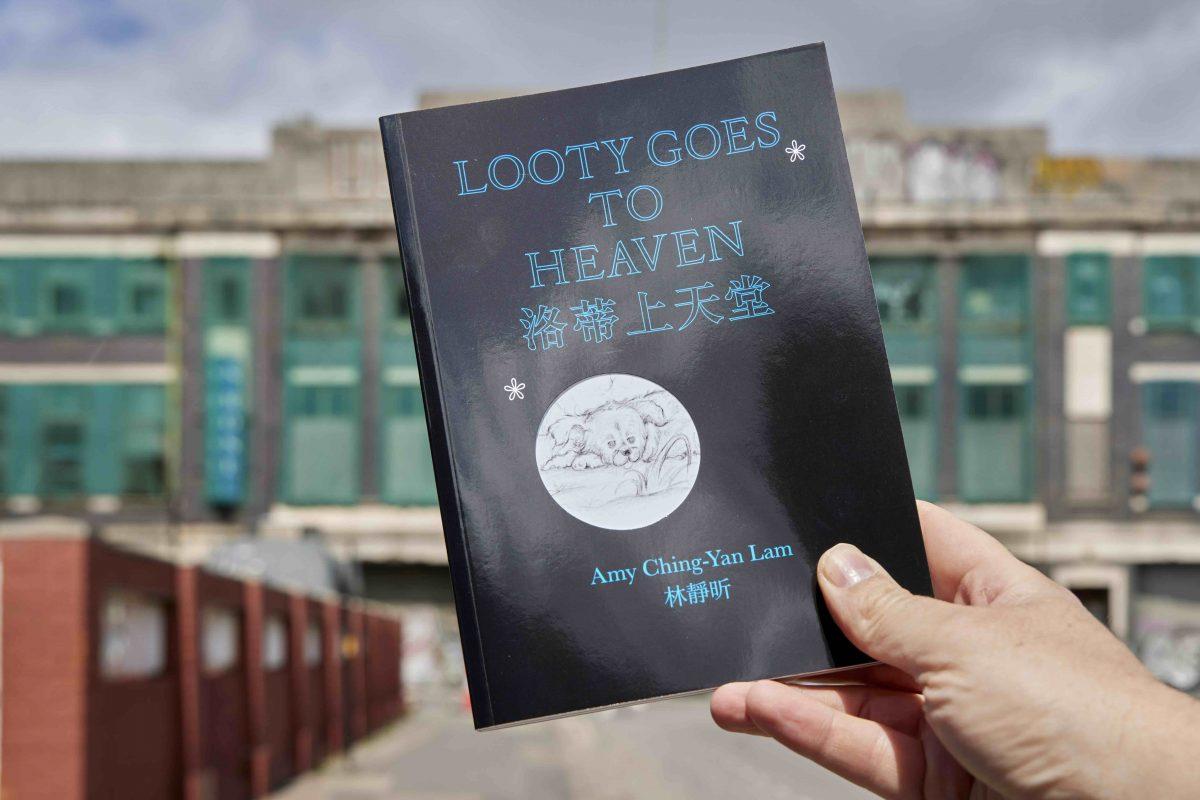

Amy Ching-Yan Lam, Looty Goes to Heaven 洛蒂上天堂 at Eastside Projects, Birmingham, UK

In 2020, the LOAC collaborators went their separate ways. Lam and I went on to present her solo exhibition A small but comfy house and maybe a dog in 2023 at the Richmond Art Gallery (RAG). Collaboration remains a central part of her practice and several works in this exhibition were co-created with HaeAhn Woo Kwon. Emerson Maxwell was a collaborator on the pastoral 3D animation of Looty the Pekingese dog. My familiarity with how Lam works came from finding my way into the dynamic between her and McCurley. So, in many ways, in this exhibition I was navigating a new artist/curator relationship.

I asked Lam what it’s like for her to work inside of cooperative relationships: “Every collaboration is different. I think what I like about collaboration is what I like about art. It’s following the signs and what the world presents to you. Like in the story of making the Richmond show, you told me about the library and the Dr. Lee collection. That’s a sign.” Lam is referring to her incorporation of selected objects from the Richmond Public Library’s Dr. Kwok Chu Lee collection into the RAG exhibition. Donated by the Master Fung Shui practitioner, scholar, and author, the collection consists of approximately 47,000 Chinese language books and objects. Lam had works from RAG’s permanent art collection hung in the library, making them available for loan to residents of Richmond, to strengthen the relationship between the library, the gallery, and their publics. “HaeAhn suggests talking to a Fung Shui expert. Another sign.” The inaugural and final works of the exhibition were shaped by a reading with Fung Shui expert Sherman Tai, who advised adding a water feature and live plants to cultivate the Fung Shui of the space. HaeAhn and Lam built a water fountain that overshot its basin out of Home Depot materials—as if performing the duality of empowerment and inadequacy that is survival under late-stage capitalism, or “doing it for ourselves.” The last objects in the exhibition were poppy plants, a reference to the British Empire’s responsibility for the opium trade and its attendant epidemic of addiction. “It unfolds when other people present you with things you wouldn’t find yourself. They give you signs, markers, new paths. There’s an element of it that’s not based on what you think you want or want to do. It’s shaped by the context—the curator, the gallery. That’s the value of it and maybe it’s what’s important to respect about each collaborator, that they’ll allow you to find a new path. It’ll be unexpected. It’s boring to predetermine [what the work will be]. It doesn’t actually express what life is like.”

Largely based on the artist’s personal experiences, the works in A small but comfy house and maybe a dog referenced the artist’s close relationships, including her family and her younger self. Lam’s priorities are made clear by the factual, unembellished way that she communicates—one reason that the childhood objects and life memories within her exhibition are so compelling to me. The exhibition title comes from a grade school writing assignment that Lam titled Me in the Future where she imagined, among other things, having a small but comfy house and maybe a dog in her twenties. In another school assignment displayed in the exhibition, Lam imagines herself as a feminist leader, bringing down not only the patriarchy but also the British monarchy. The artist doesn’t use facile tropes of childhood innocence, sweetness, softness and girlishness. She presents her memorabilia plainly, without diminishing children and the meaningfulness of their stated values and interests. Lam knows and trusts that we have all been children and are literate to the meanings and associations of toys and children’s creations in relation to personal history and becoming. She isn’t relying on sentimentality to frame the work. Perhaps this is what artist and audio producer Aliya Pabani, a friend and frequent collaborator of Lam’s, meant when she said that the artist’s work “captures what’s literally happening with humour and levity, without compromising seriousness.”

I tell Lam about a realization I had when viewing works in the RAG exhibition. “When I’m looking at your work, sometimes something will strike me as funny. Then I realize it’s because I recognize something about myself. Then I feel embarrassed. Then I find that funny.” We both laugh, possibly in recognition that what’s funny can also be profoundly messy and vulnerable.

a small but comfy house and maybe a dog at Richmond Art Gallery, BC, with HaeAhn Woo Kwon. Curated by Su-Ying Lee

.

a small but comfy house and maybe a dog at Richmond Art Gallery, BC, with HaeAhn Woo Kwon. Curated by Su-Ying Lee.

Humour was a foundation in LOAC’s work. I ask Lam how she defines humour now. “People would always ask me his question and I’d try to dodge it.” As it turns out, Lam had to research humour for a piece of commissioned writing: “Why people laugh is complicated. It’s a very social thing and when you recognize you’re laughing at the same thing, it’s valuable. It’s a clarifying way to determine who is with you. It’s an embodied feeling that creates the sound. It’s political and social. It exists in this world of ideas.”

Surrounding us in the restaurant are framed vintage ads from Hong Kong and neon style signs. Like in Hong Kong, true neon lights have been replaced by LEDs. Hong Kong, where the artist was born, appears in Lam’s writing and visual art practices, so I had assumed that it occupied more space in her thoughts. But according to Lam, it’s more so her parents’ comments and memories of their former home that are meaningful to her.

We’re discussing the progress that Lam is making with her next book, Property Journal, which was shown in calendar form in Richmond, between her bites of the classic dish Hainanese chicken rice, my mouthfuls of a messy pineapple bun chicken sandwich, and sips of strong Hong Kong milk tea. Each journal entry documents a conversation or encounter she has had with a topic most of us in Toronto are fixated on: property. Those mentioned in the journal are made anonymous, their names replaced by objects, such as “Rice Cooker” or “Toaster.” Lam tells me that she’s editing the journals to bring out “more of the emotional truth of it.” “As I’ve been editing, the thing that I realized is, it’s my journal, so I can edit whatever I want.” We both laugh at how plainly truthful, yet seemingly unorthodox it is to state this.

What began as a diaristic subject-based series of observations, became Property Calendar, now on its way to a new incarnation as the book Property Journal. Interested in her thoughts on this manifestation and her movement between visual art and literature, I ask Lam about the relationship between her writing and her visual art.

“I don’t know if they express different things, but the thing that’s most different is the actual process of doing it. Writing is very internal in some ways but art is too, in the conceptualization. But writing stays internal for a longer time. You don’t need to collaborate with people until you get to the end stages of it. But for me I don’t draw. I’m not a painter. I always need to work with other people. So, in art, other people come in a lot earlier and my visual art is made through collaboration. It allows me to work with other people and learn about other contexts, provocations. But then I feel like in the end, like with an install, both art and writing still have the same thinking that’s required—of putting together the puzzle of the flow, how the audience will experience it over time.”

I know that Lam began her studies in English Literature and Writing (Waterloo University) with a minor in computer science, followed by a Master’s Degree in Creative Writing at Concordia, so I’m curious about this early progression away from literature towards visual art. Visual art isn’t part of her educational background. “I hated my Creative Writing program at Concordia so much. This is the story that I tell when people ask me at book launches. I always wanted to be a writer. I love reading and writing. Then I got into this program.” This was around 2006-08, and then in 2014-17 the “Me Too” movement publicly revealed that many of the professors in the program were abusing their positions with their students. Although Lam didn’t experience this herself, it was palpable in that environment in the years when she had been in the program. “It was dominated by men. It was a social scene where you had to go out and drink with them. If you didn't, they didn’t pay any attention to you.” Her thesis advisor all but avoided engaging with her work. It was not what Lam had expected from her graduate studies. “I had a pretty good undergrad experience. I was into experimental writing and I learned all this weird stuff like the approaches used by the Oulipo [short for the French Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, a French literary movement]. French writers who wrote under extreme constraints like a novel written without the letter ‘e’. I thought it was so cool!” By contrast, the Concordia program was “old fashioned” and focused on systematically building a career through networking and upholding entrenched industry practices. A reason Lam had wanted to study there was because her thesis advisor ran a program abroad. When she attended “it was just more famous white American male writers flirting with students who looked up to them. At the time I didn’t even have the language for it, but it wasn’t what I liked.”

Around 2007 Lam met McCurley at a zine fair. When someone asked her to do a comedy show, she asked him to do it with her. Although she hardly knew him, she liked his zines. From then on they collaborated steadily. When she was dissatisfied with the writing program, she had an escape organizing projects with McCurley, shaped on their own creative terms. By the time she graduated from Concordia, she was disillusioned enough to leave writing behind. Around the same time, she first visited a contemporary art museum. “I was like OMG what is this?! I went to the MAC [Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal]. It was just a whole other world that seemed more exciting. I was like, you can do anything?!”

With Baby Book, Lam has come back to writing without following the approach prescribed by her graduate studies. Responding to the question of how she defines successful writing, she muses “I guess there’s a feeling I get when I write something I like. It hits at something. A feeling of discovery and also emotional truth. And then sometimes after, you ask ‘is it good?’” After a pause for laughing at the inevitable self-doubt, Lam reflects, “But I guess if it is really good, when you re-read it, it still has this emotional truth. You feel discovery. And that’s what’s nice about poetry. It’s not linear. That feeling can still come about because it’s abstract. Success in the worldly sense? l wish I could make more money.”

I wanted to understand how Baby Book came to be. “I worked on the manuscript for a long time. I started writing in 2018. I wasn’t even sure it was poetry and I definitely didn’t know it was a book. I kept expanding it and out of this poem [the first poem in the book, ‘The Four Onions’], came all these other poems. I worked on that all through the pandemic. As a book, there were so many different versions because I was discovering the form of it and what I could do. All the poems have had different versions. There were so many versions of the book because the hardest part was sequencing. And every time I re-sequenced it, I would re-write the poems. In some ways it was really fun because it was like a puzzle. I submitted it to presses and I ended up choosing Brick because they only publish poetry and they’re very supportive of the object that the writer wants. In literature, it's not like the art world where if you make an artbook, people understand that you’re an artist and you care about what it looks like.” Lam speaks about how the placement of one thing alongside another creates different meanings, whether it’s in bookmaking or exhibition-making “It’s like when we were installing at the RAG and we moved things a foot or changed the angle. It’s basically exactly like that.” Though each of the individual artworks or texts may have come to its moment of completion, an unknown number of stories remain to be told through a different act of arrangement, narrativizing configurations that can be influential and powerful. Lam recognizes that there are many possible “truths” that can be brought out in this way, like the situations that are at once funny and unjust—a pairing that appears in both Lam’s exhibition and book.

Baby Book came out around the time a baby was joining Lam’s family. I had become familiar with the Lam family through proof-reading the Property Calendar. The anticipation of Lam’s sister Bessie’s baby was a significant part of the story. I met Bessie in-person preparing for this profile. We talked about our families’ migration histories and her and her sister’s relationships to Hong Kong. In chapter one of Baby Book, the writer asks what it’s like to be a baby in “the world’s most expensive city” and for parents to raise a baby there. The sisters—Amy born in the most expensive city, Bessie in Alberta, both raised in Calgary—spent summers in Hong Kong until their grandmother passed away. Speaking with Lam, I don’t get the sense that the island has a significant emotional draw for her. Bessie believes that Lam’s deeper knowledge of Hong Kong comes from her investment in research, as an artist. I come away understanding that Lam has always been a high achiever across the board—academic achievements, creative works, care and support for her family and community. In Chinese, we would say that Lam uses heart/用心/ yòng xīn. It means to look, listen, think, do things, treat others, with the utmost care, and to pay attention to detail.

Photos by Yuula Benivolski

Several months pass, too quickly and easily. I want to check-in with Lam again. It’s now early winter and we’re about to enter 2024. A lot has happened. This time, we met at my local Portuguese bakery and café, which is not that different from a cha chaan teng considering the Portuguese pastel de nata is the prototype for the Hong Kong custard tart. The café is brightly lit, busy with Portuguese neighbors and other Toronto residents who have discovered its unpretentious, affordable charms sipping coffee, having meals from the hot table, and buying bread. We drink cheap tea infused from tea bags and catch up. Lam is set to teach a film class for 240 students at McMaster University over the course of the coming semester; she’s turned forty, and recovered from her second time with COVID. She’s happy not to be traveling and instead, has been spending time babysitting. On October 8, 2023, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu formally declared war on Hamas, the days, and months that follow are filled with the human rights violations taking place against Palestinians, reverberations and actions are happening across the local and international art communities, including institutional silencing and protests.

At our booth, beside the wall of windows, Lam shields her eyes from the bright afternoon sun: “I’ve been thinking about this year—it was a huge year for me. I turned 40 and I felt like the show at the RAG kind of addressed that in a way. I feel conflicted or it feels complicated. In one way I’m really excited about where I’m at as an artist and the kind of work I’ve been able to do and the kind of work I want to do. I want to continue writing and think about how I want to keep making exhibitions. It feels amazing to have this body of work completed. Because during the pandemic it was in progress. It feels nice to have completion. I guess it feels complicated because of the time we’re in [referring to Israel’s war on Palestine]. If you asked in September, It would have been a different answer. It’s December and this morning an artist pulled out of CONTACT [CONTACT Photography Festival, Toronto, because of its funder, Scotiabank’s, ties to Elbit Systems, a major Israeli arms manufacturer] and all this stuff with art institutions in this city and around the world. It doesn’t feel very motivating to go and make exhibitions, to have them show in museums. It’s not my goal anyways, but it feels very fraught participating in the art world. It’s so hypocritical. In one way everything has changed in the last few months, in some ways it’s liberating. Everything that I kind of knew is proven true. All the DEI [Diversity Equity and Inclusion] statements in the summer of 2022 and all their programming around it. It’s not true. They don’t actually believe in these things. The masks are off. Art was never about getting into these institutions anyways. But, how do you keep working?”

I know about Lam’s various community involvements, advocacy, and resistance and ask her if she wants to talk about activism and organizing at all. “Not really. I guess what I’ll say is my political commitments are important to me and it’s also expressed in my work. I don’t usually describe myself as ‘an activist and artist’. Activism is part of a collective movement. It’s not solo.” At the foundation of Lam’s practice is her unwavering belief that our humanity is interconnected, making us collectively responsible for demanding and manifesting justice. Lam faces the dynamics of power and inequality, present in every one of our lives, with a subtle humour that reflects the insidiousness of living under cruel conditions.

So, what do we do when we need to make a living amidst the silencing and repercussions of speaking truths? “The answer is figuring out a new way of working. Everything has to be more strategic. Your choices really matter. Your choices have always really mattered. And now it’s way more evident.”