The following piece contains material that may be especially distressing for some readers. Reader discretion is advised.

The Belleville Club at 210 Pinnacle St. is closed, but I’m two weeks late for S’s celebration of life here anyway. I found a dive bar around the corner to sit down and get this started. There’s a small pile of thick dust beside my tall glass of Coke, but the spill on the first table I tried was still tacky, so I think I made the right choice. I wonder if S was ever here. I wonder how many times he walked across one of Belleville’s old bridges or posted up underneath them for teenage misadventures. He grew up in this town, and he’s probably buried here too. Had I arrived on time I would know, but I’m bad at this. I’m not sure how to mourn, but my attempt is permitted at this table.

S and I lived together with a third roommate in a little house in Antigonish, NS for which none of us had a set of keys. The doors were open or not there at all. I walked in on him in the kitchen the morning after a dinner party to find him wearing nothing but wool socks, underwear, and a plaid shirt dancing to Michael Jackson’s “Billy Jean” like Tom Cruise in Risky Business. We had attempted to make a duck for our dinner party without a recipe or the wherewithal to find one. Someone recommended suspending it above the bottom of the pot to allow its oils to fall away. Our basket hung too low, and the bird was immersed in hot grease when we tried to take it out. I can’t recall what we served instead but the duck was inedible, and the house was not fit for guests. S’s early morning kitchen dance might have been intended to fan away the wet-dog stench of our culinary disaster.

He died suddenly of cancer, at the height of his professional powers, teaching in a prestigious Psychology Dept., and spending time with a wife and children I never met. We had a brief chat on social media after he announced that his cancer was back. I told him about mine, and my recovery from it, to instill hope. He was happy for me, but I got the sense from the brevity of the exchange that he was dealing with a death sentence, courageously “fighting” nevertheless, as we’re told to do.

I wasn’t around for D’s death either. I heard the news when I was painting a room for my eldest daughter in the weeks before she was born. The last time I saw him was at another dusty, sticky bar across from the housing co-op near Front St. in Toronto where he and his brother were raised by their single mother, and which he never left. I was borrowing a snowboard for a trip to Quebec, or I might have been returning it with a broken binding, cracked from the cold of Mt. Tremblant. He was characteristically forgiving. As we sipped our drinks D's friends from this local (he had a few) dropped in to joke and move on – he was beloved, still. Toward the end of the visit, he broke down into perplexed tears telling me about a young neighbor in the co-op who had killed herself a couple of weeks earlier. He died not too long after that, also young and alone. Looking back on D breaking under the weight of his own news, on his inability to assimilate this death of a friend, it seems like he knew his own was around the corner, and that squinting, teary-eyed confusion was a result of his hunch about an impossible, inevitable end.

Like S’s, I remember D’s buffoonery, too, performed deliberately from the most widely visible improvised stages. The first time I saw him, he was playing a guitar badly, with no knowledge of the instrument from a mezzanine at the climbing gym. Strained shrieks, wailing, and mock sincerity signaled that it was meant to feel vaguely like a 90s indie-rock tune. He tried something a little different from my balcony in Montreal during a visit years later in search of what addiction specialists call a “geographic cure.” Shortly after entering the apartment, he made his way to the balcony and began addressing passers-by with the few French words he knew, in no meaningful order, but with an unmistakable Anglo-Torontonian conviction. Montreal wasn’t the best place for the healing D needed, and I was a wreck at the time too, not as supportive as I could have been, but by his side for the stumble.

I’m stuck on the facts of his death or its record – in a digital display, in words, and in a picture. I was told that he’d been dead for two days when his mother found him on his bed. The moment of death was certain, shown in the time-stamped, lost heart rate display on his Fitbit. She had taken a picture of him in this state, his arm tied off with a belt chasing its tail a few inches over that device. The picture cut a path through D’s celebration of life (for which I was on time), but it got to me only in story form, from a close friend struggling with similar problems. He carried the ghost of that image in his darting, also perplexed eyes.

A while back, under the spell of some undergraduate philosophy lecture, I attempted to read a passage from Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time to D. He was rightly skeptical. It could have been any passage at all that elicited his allergic response, but let’s say it was this one, about death:

The greater the phenomenal appropriateness with which we take the no-longer-Dasein of the deceased, the more plainly it is shown that in such Being-with the dead, the authentic Being-come-to-an-end of the deceased is precisely the sort of thing which we do not experience.1

He might have said any number of things after I finished, but let’s say it was: “Stop! Why are you doing this to me!?” As I recall it was the idea, or figure of Da-sein (literally “there-being”) that captured my imagination, and that I thought D might appreciate too, as we were both just there in those days, trying not to fall and falling all the time. I didn’t give much thought to what Heidegger had to say about death, about the “authentic” mode of being in which we’re oriented toward it as a termination of our “own-most possibilities,” a strictly “non-relational” end to an otherwise always relational existence. And I didn’t give much thought to his now-chilling claim that we are inauthentic when relating to the deaths of others, as mere facts, or cases. I’m not sure how helpful it is to think about all this now, looking back on these lost friends’ lives, on the case of a terminal cancer, and the fact of an overdose. My certainty about these causes doesn’t make them any less heart-breaking, or bring the terror of dying under control. And while I’m not so practiced at mourning, my devastation feels authentic, pace Heidegger.

Everyday Palestine

Surrounded by equally certain facts and cases of Palestinian deaths, just as perplexing, inassimilable, and devastating as the picture of D’s body, I need to learn to mourn or cope better. But the cases couldn’t be more different.

The journalist Nahed Hajjaj recorded the death of a boy on the floor of a crowded and chaotic hospital, with a medic and his mother at his side. She had lost all her children in an IDF attack on a school East of Deir al-Balah in the Gaza Strip. Entering the frame from the left after the medic quits monitoring vital signs, she falls to her knees and we catch a glimpse of the boy’s lifeless doll-eyes – a sure sign of his passing that she too must have noticed, but her hopes are raised when he involuntarily pulls in a rattling breath through a locked jaw, then another, and a last, then stillness. The video cuts as she tries in vain to revive him while the medic looks on helplessly. It was circulated on an Instagram page called “Everyday Palestine” – an aptly named one recalling Heidegger’s sense of the “everydayness” of death as a lamentable fact that, when brought to the attention of the living registers as a “social inconvenience… a downright tactlessness, against which the public is to be guarded.”2 His view is that we do a fine job of guarding ourselves with various strategies of “tranquilization” including offering consolation, rituals of mourning, and retreating to the protection of “idle talk”: “One of these days (we) will die too; but right now it has nothing to do with us.”3 For him, it’s rather one’s own death that must be reckoned with in an authentic life, anxiously and with a resolute future orientation. The news from Palestine, for me, precisely in the everydayness of its accumulating, documented facts and cases reverses this temporality. Once again, I’m late, arriving after the venue is closed and the clock is stopped, looking back at the death of others like a bad guest or an absent friend.

Still from video by Nahed Hajjaj. Posted on Instagram

The Sight of Death

In a 2006 “art-writing experiment” TJ Clark pours over the details of two paintings by Nicolas Poussin titled Landscape with a Calm (1650 – 51) and Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake (1648). The book’s journal entries were composed while he was working on a more “polemical treatment of present-day politics… (on) Capital and Spectacle in a New Age of War,” just ahead of the spectacle of 9/11.4 Poussin’s “calm” might be read as a retreat, like Heidegger’s “tranquillization” from such shocking confrontations with death were it not for Clark’s insistence that the paintings are arguments against just this ecology of images. Their stillness is a reminder to take time in our looking, whether at the Getty or the National Gallery in London with Poussin’s landscapes, in front of our TV screens watching the towers crumble into rising plumes of smoke and ash, or on our devices with Hajjaj’s “everyday” horrors in Palestine.

Nicolas Poussin, Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake (1648).

Landscape with a Snake has three focuses of action against the backdrop of a town nestled in a lush, wooded valley and reflected on the surface of a glassy pond. In the middle distance we see a “washer woman” on her knees with arms outstretched in exasperation. She looks to her left as a running man approaches from around a darkened corner following an extended, clawing hand with his gaze cast back at the death-by-a-snake in the foreground. Clark spends time on the tangle of limbs and coils emerging from the crime scene, noting the snake’s “repellant” evocation of intestines, of abjection, or “an inside coming out” to claim its victim.5 Elsewhere it’s the limpness of that victim’s body, veiled under the “drapery” of the serpent that catches his attention, or the snake’s sheer “plasticity.” Moving away from that “sight of death” to its effects, he remains focused on the imprint of death on the body - on the economy of Poussin’s single black brushstroke describing the horror-stricken open mouth of the witness, and the washer woman’s expression which discloses the “ill will of the world impinging on her.”6 It’s these facts of the painting that are responsible as well for the impingement of it on Clark. “Death in Poussin” as he writes, “is exactly not to be deprived of its factuality.”7

Recognizing the artist’s taste for narrative, we are told that the picture is likely an illustration of the story of Cain and Abel in the Book of Genesis, or an aftermath of the episode where Eve is the washerwoman, Adam the running witness, and the serpent a transformed Cain devouring Abel.8 Poussin’s picture is concerned with the representation of a fact and a terrible one. But it’s a fact stilled and laid out for our unhurried contemplation, unlike the faster-moving facts of death recorded in the televisual and digital culture against which Clark writes. To mourn or to cope, I wonder how Hajjaj’s image of a group of three swirling in the mess of a more political death might also be slowed down and read as the world’s first murder, like the Genesis episode, instead of just another in the ruined landscape of the Gaza Strip.

Poussin and Hajjaj (details)

Necropolitics

The Cameroonian historian Achille Mbembe has views on death, and of death that might come closer to what we’re seeing in Palestine than Heidegger’s. More pictures:

Lifeless bodies are quickly reduced to the status of simple skeletons…relics of an unburied pain… strange deposits plunged into cruel stupor…In these impassive bits of bone, there seems to be no ataraxia (calmness): nothing but the illusory rejection of a death that has already occurred… In other cases, bodily integrity has been replaced by pieces, fragments, folds, immense wounds… Their function is to keep before the eyes of the victim – and of the people around him or her – the morbid spectacle of severing.9

The passage is from an essay on what Mbembe calls “necropolitics,” an account of death as a tool to intimidate and control populations, manage the displaced, and decide from on-high who lives with freedom and who can only dream about it. When he wrote the essay in 2003, in the midst of the Second Intifada and in the wake of 9/11, he called necropolitics the “nomos of the political sphere” globally - a name for our dealings with one another and with governments near and far that says more than “democracy” and “sovereignty” do about who we as a species have become.10 The case of Palestine for him is paradigmatic, a “colonial occupation,” and now a genocide that qualifies as the most “accomplished form of necropower to date.”11 And so it is that the term comes closer as well to the experience of death captured by Hajjaj and others reporting lately from Palestine, than Heidegger’s a-political, future-oriented being-toward a “non-relational” end. Mbembe’s, Hajjaj’s, and even Clark’s sense of death is always relational, not so much projected but stuck in a present marked by death, where survivors scatter in its wake without opportunity for mourning. The way he puts it, the present in places like Palestine is “but a moment of vision – a vision of freedom not yet come,” and of those restless bones, bodies and wounds “kept before the eyes.”

These images come to us in the safety of our homes from afar. And maybe Heidegger is right about the “idle talk” that dulls the shock of them. But Mbembe’s naming of a necropolitical order is meant to insist on the proximity of colonial and postcolonial wars and their violent deaths to our zones of relative safety. It is our order and our world for him, and it behooves those of us who catch a glimpse of it to cut-through idle talk, to protest, or to at least do the work of mourning its immediate victims.

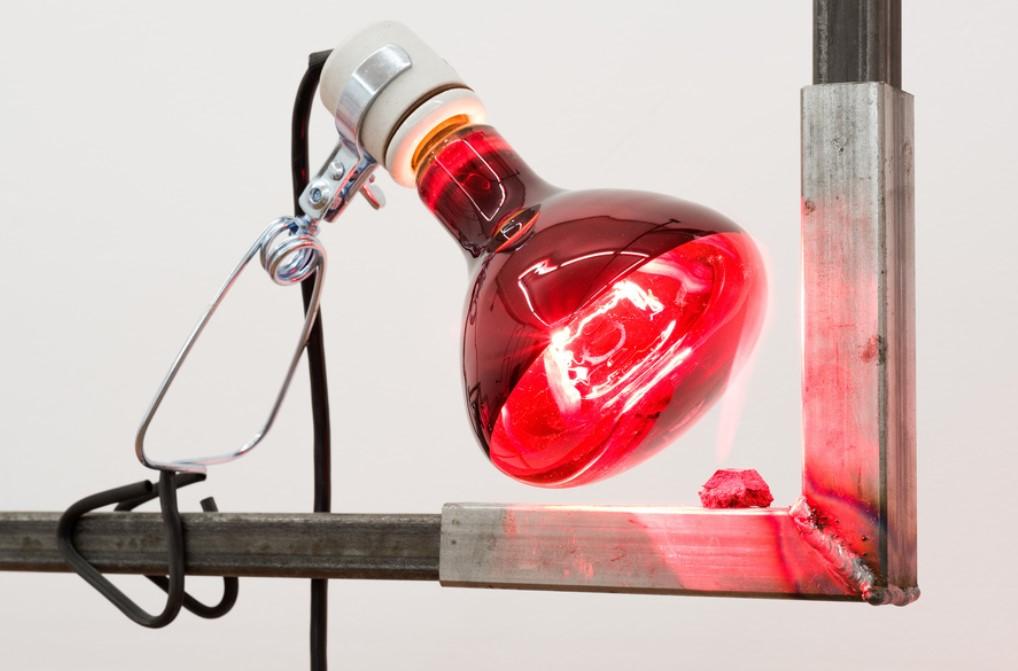

The New Haven-based multidisciplinary artist Azza El Siddique might be up to this kind of thing in her work, with an eye on the necropolitical stage of her native Sudan, now in the grips of a Civil War. She escapes the paralyzed present Mbembe describes by looking back, way back historically for lessons in mourning, drawn from Ancient Egyptian and Nubian funerary rituals, burial practices, myths, images and scents of death. In several of her sculpture installations she burns bakhoor and sandalwood, scents associated with Muslim Sudanese burial rites and studied by the artist in an apprenticeship with a Sudanese perfumer.12 This and other transformations, through corrosion and rust, light, water, and heat she understands as processes of change that transfer rather than terminate energy. In her image repertoire – pyramids and ziggurats, cracked pottery and African masks, pharaonic sculpture busts and snakes with heads at both ends, the scientific view of change is given a mythic cast. El Siddique’s cobra sculptures laid out on plinths and moving in opposed directions like an unfurled ouroboros seem a long way from Poussin’s Snake. But like Poussin for Clark, El Siddique insists on death as a condition of bodies, or as a fact, underlying mythological or religious views of it. Still, her titles save some space for hope and optimism: “begin in smoke, end in ashes”; “in the place of annihilation, where all the past was present and returned transformed”; “fire is love, water is sorrow - a distant fire.”

begin in smoke, end in ashes, pt. II (detail, 2019). Sourced via

Azza El Siddique and Teto El Siddique, fire is love, water is sorrow - a distant fire (2021).

Azza El Siddique and Teto El Siddique, fire is love, water is sorrow - a distant fire (2021).

The last title is for a two-person show of Azza and her brother, the late Teto El Siddique’s work. The critic Merray Gerges compiled a number of interviews with students, peers, fellow artists, and professors who had known Teto before his untimely death. They remarked on his passion and sensitivity, his humour, energy, and demands as a teacher, and his “unfulfilled promise” as an artist, as well as the antics that passed in his practice for a working method. A former classmate recalled “a stretchy leopard-print body suit” that made its way from one of Teto’s dollar store hunts into a painting.13 In his sister’s posthumous dialogue with him as well we get a sense of his wildness and gift for improvisation, of his artistic buffoonery. In the exhibition, Azza responds in small works installed in her signature metal framing to Teto’s large and loud paintings of restless phantoms twisting their way out of fiery backgrounds that look like sunset skies on another planet. In one of Teto’s paintings, a figure with an upside-down lotus blossom head turns to the viewer as though caught in the act of shitting a flower into a basket. A detail almost makes sense of the scene, but not quite: his feet are firmly planted in boots made from watering cans, another of the artist’s dollar store inventions that, one imagines, he may use to sustain the flower’s bloom.

If I could I’d make pictures like this of D and S, in the glory of their own buffoonery. To mourn, and to remember, and to celebrate their lives, late as always. And I wonder how pictures like this might help us to honour the anonymous bodies piling up, bagged, scattered, wounded, and martyred in Palestine, in Sudan, and elsewhere far from our homes on the quiet side of the necropolitical order. What would their teachers have said about them, or their friends? Would those stories wrest them from the anonymity of all this bad news and make them into the kind of individuals the world deems worthy of commemoration?

At that Montreal apartment where D tried to get away from all his trouble, I saw a picture like the one his mother took and shared of him on his deathbed. Just as inexplicably, my landlord showed me a picture he had taken of our superintendent keeled over on his sofa where he died alone, in a bachelor apartment underneath mine. Such pictures are a long way from Hajjaj’s, still further from Poussin’s in the garden of Eden, and El Siddique’s in the ancient world and in her brother’s imagined one, with electric sunsets and funny boots. I hold these together to discover something about the sight of Palestinian death, an image world from which there is apparently no escape. In doing so maybe I’m hoping for one of those alchemical transformations that power El Siddique’s imagination and help her cope with loss. Maybe in marking the personalities of S and D, arresting them in pictures, and crossing those pictures with Poussin’s and El Siddique’s, there’s a way past the egocentrism of coming to terms with one’s own death without relation to others. There’s a risk of sublimation here, of tranquilizing the already mediated experience of Hajjaj’s pictures and of the unfolding history they capture. But there might also be a chance that those deaths, in this arrangement of gods, pharaohs and serpents, friends in kitchens and bars, and brothers, can be brought closer, slowed down and felt as directly and viscerally as a death in the family. And then, maybe it’d stop.