Audie Murray in studio. Portrait by Mika Abbott

I know a lot of things about Audie Murray. I’m not sure how much of it is relevant to her art practice. I know her brother works on trucks in his spare time and I know what high school she went to. She has told me about her dreams. I know her child’s name and how she takes her coffee. I know how her kitchen is arranged and what is in the fridge: Babybel cheese, firm tofu, and at least three varieties of berries. She told me that when she is depressed and the idea of cooking food is unimaginable, she eats cubes of tofu with nutritional yeast. It is also one of her son’s favourite things to have for lunch. I often wonder how much I can know about someone’s art based on being friends with them.

Murray grew up on Treaty Four land in oskana kâ-asastêki (also known as Regina, SK). She is a Contemporary Cree-Métis artist with community connections in Lebret and Meadow Lake. In the past, she has worked with beading, video, performance, text, installation, and photographic processes but ultimately doesn’t claim any one way of working as a focus of her practice, opting instead to work through close readings of materials. She conducts research which, in her practice, moves beyond the usual academic associations (books and archives) and toward a more expansive notion of attention. With curiosity and vigilance sustained over time, she contemplates the way that binaries like urban/rural become a lived duality rather than forces held in opposition.

Two days a week I arrive at Murray’s house just as her son is waking up from a morning nap. There is a moment where his cheeks are lax until he notices I am in the room and his face usually snaps into a wide smile, showing his tiny teeth and their little gaps. On these days, Murray and I cross paths briefly, just long enough for a general check-in: what did you do this week? What’s going on in the studio? Sometimes she will show me something in progress. We chat about copper sulphate or lamp black for five or ten minutes and then she heads to the studio for a couple of hours.

One night in October, we went to a conveyor belt sushi restaurant to talk about her practice. I felt that the usual ease of our conversation was disrupted by my shift from nosey friend to nosey writer. Once I began asking my questions about Murray’s practice, it felt like we both forgot how to speak to one another. Later, I wonder if it’s because we mostly talk about endless email chains, production budgets, grant deadlines, and other inane art gossip. There is a type of ‘professional’ demeanour that we often lament or mock together. We both understand that this language has its time and place but were just startled by the emergence of this third force in our conversation.

A few weeks later she sent me some tests from her studio that would eventually become a trio of works called “Extraction” (2024). They consisted of ink washes made from steeping fresh tobacco leaves or flower petals. Hovering over each of these fields of colour is a grid of gold-flecked blotting paper, nine pieces in all. These pieces were sewn together with single strands of her hair. Small blotches of sebum mark the surface of the paper, itself as thin and delicate as a strand of hair. They are very softly abject. While describing the work to my mother she commented on the “mingling of intimacy and anonymity” in the work. Though it’s made from traces of the artist’s body, the only thing I can see of Murray in the work is her sly absence.

Murray's work questions cultural presumptions about Indigenous identity and, in particular, the way the settler gaze demands legibility.

I met Murray at a party while I was in grad school. She was attending the University of Regina as well and she gave me a ride home. I remember talking about the Pixies with her. We were in a group show together in Montreal and I remember sending her a picture of the sale sticker beside her piece at the opening. A couple of months ago that piece entered the collection at Le Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal. She moved to Vancouver until the pandemic and we began to hang out in those nimble days emerging from lockdown.

In the run-up to her exhibition To Make Smoke (2024) at the Mackenzie Art Gallery (MAG), we spoke about how the art world we saw looking from the distance of educational institutions was so vastly different from the one we are now navigating. We spoke a lot about the distinction between being popular and being privileged. There has been a shift in the way Indigenous artists are represented and engaged by institutions. Throughout our conversations, we discussed the emergent assumptions and pressures that this wave of institutional interest has produced.

Being liked at a distance by many people is, in many ways, just that. It brings one closer to what appears to be power but is, in reality, just so tenuous, precarious, and immaterial. The ability to draw eyes in your direction may hold the potential to generate money or power, but for many artists, that potential will never bear fruit, especially for artists whose popularity is tied to their ability to marshal an intersectional identity in a way that is both legible and useful to the institutional agendas that sometimes drive curatorial interest.

For Murray, these forces are felt in a very direct way, especially in the work she is showing at the MAG. Murray makes work that questions cultural presumptions about Indigenous identity and, in particular, the way the settler gaze demands legibility. Under the banner of inclusion, diversity, or reconciliation this often unspoken demand to ‘understand’ carries with it an equally silent expectation that this worldview be tailored in a manner that does not look to disrupt the colonial settler state or White supremacy. To Make Smoke is an expression of these institutional forces and colonial frameworks that are felt at different densities as they run through communities, friendships, families, and selves.

To Make Smoke (2024), installation view at Mackenzie Art Gallery. Photo by Carey Shaw

To Make Smoke (2024), installation view at Mackenzie Art Gallery. Photo by Carey Shaw

I came to the gallery one day and tried to keep E occupied while Murray worked on a large installation, scrubbing ash onto the surface of the gallery wall with her fingers. The ash is a collection of burnt sage, sweetgrass, and roses. She moved across the gallery slowly, rubbing with one hand and softening the spirals with a bit of water. I think a lot about drawing as an act of devotion and prayer. As an accumulation of small marks, drawing tracks the time and attention of its own making and often bears elemental traces like the particulate found in smoke. Each arch of ash is both a record of the last and a schematic of the next.

When I run out of goldfish crackers and rice rusks, E gets restless and we wander the gallery together, avoiding trash bins, ladders, and buckets of high-gloss paint. I shepherd this small child around for as long as I can before he follows the inevitable curve back to his mother. When one of his parents is in earshot, he always flows to them like water and rather than constantly step around him, Murray puts him in a Japanese-style harness and hoists him onto her back while she works away at the wall.

Murray has worked with smudge ash in the past, using it to draw the negative space around images that are central to the Ininew creation narrative.1 In “PAKONE—KISIK" (2022) she maps out the constellation for which the drawing is named (known as the Pleiades in the European star chart). This is the hole in the sky. It’s where the Ininew come from and where they return while sleeping—connected by a string of spider’s silk. Like many of Murray’s beaded works, these drawings help to bind her attention.

After Murray has finished a section, we stand back and look at the warm grey field “It really looks like smoke” she says. We talk about the spectrum between presence and representation in the work—how it is both a representation of burning and a record of its aftermath. In the burning, smoke peels away from the ash like petals fall from flowers or limescale collect in the kettle. Each of these small things is a record of time and devotion, no matter how mundane it may be. Each match struck is a message and every spark is a signal.

Throughout the exhibition, there are allusions to connection that range from oblique to more direct. One that engages many densities of connectivity is a beaded chain sprouting small flowers. Titled simply “The Chain” (2024) it brings to mind the multiple applications of binding like the ones that create kinship as well as the ones that restrict freedoms. It alludes to the different contexts that make bondage an unbearable source of both pleasure and pain, as well as a simple reminder of our connectedness to other people, and the environment that surrounds us in the past, present, and future.

Stephen Mussell is Murray’s partner, co-parent, and an Indigenous rights lawyer. He has written numerous times about Indigenous policy and self-determination. “I love Audie’s work,” Mussell tells me one day as he drives me home from spending an afternoon with E. “It comes from her ideas, and her experience, and her politics. Her work comes from a really authentic place.” I often hear him discussing particularities of Michif identity and community at social gatherings with passion. I love seeing him collapse with laughter and affection for his child.

Photo by Mika Abbott

An image of “The Chain” (2024) wrapped around Murray’s wrists illustrated a piece Stephen wrote on the prominence of the Powley decision in determining the rights and establishment of Métis communities in the eyes of the settler state.2 Mussell makes several rebuffs to this strategy for determining and upholding the rights and status of the Métis people. From his perspective, Métis communities have always drawn on their connections to First Nations to orient themselves and their rights. With the increased reliance on the Powley decision, these determinations are being made in reference to the dictations of the settler state rather than through ongoing relationships between these Indigenous nations leading to a trend of internal and external colonization as a means of establishing a framework for Métis rights and identity.

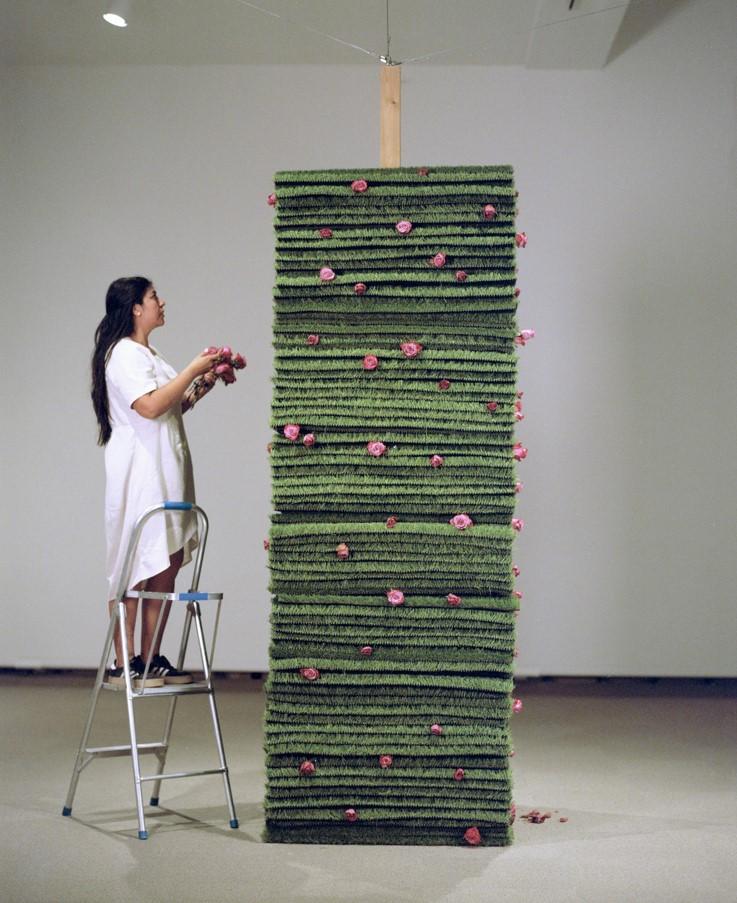

Many of these political questions are present in To Make Smoke but none are more insistent than “Rootless” (2024). The piece is a monumental square column of astroturf sheets stacked and studded with pink roses which have been slid between the layers. One might expect the contrast in the piece to be between real roses and fake astroturf where one is cast as authentic and the other as an imposter but the twist Murry makes on such a simple dichotomy is the deployment of the rose as a product of capitalist intervention. Throughout the run of the exhibition, the roses wilt and dry, unable to get sustenance from the astroturf or the hermetic environment of the gallery. Periodically, they are replaced with more pink roses driven straight from Costco. From certain vantage points, the piece touches on ideas about imposters and imitation but it also engages questions about time and connection. Murray’s practice is sustained and nourished by relations that stretch across generations; they are lived connections that have taken time and attention to cultivate and maintain. Along with her commentary on imposters, she has created a counter-monument of sorts to the connectivity that she fosters and, in turn, nourishes her.

“Rootless” can be seen partly as a lamentation of the anxiety that runs through these more generative community connections. The increasing prevalence within settler institutions of ethnic fraud is a phenomenon that continues to necessitate vigilance among Indigenous communities.3 For Murray, this issue is inflected by instances where reconnection leads almost immediately to monetization of one’s newly acknowledged Indigenous identity. For people who grew up in highly assimilated families far from the community they are now claiming, one might wonder what the revelation of a relative from the 1600s might mean in the present moment. In all of our discussions, Murray says that her frustration is not with people who are reconnecting to their Indigenous communities, because finding a way back from the violence of colonization and forced assimilation is important. What she finds frustrating are those who are quick to take advantage of resources designated for Indigenous people when they have benefited from the ability to pass as white and have very limited lived connection to traditional ways of knowing and living.

Audie Murray's studio. Photo by Mika Abbott

Since graduating from her BFA degree at the University of Regina, Murray has been producing a series of pieces using worn socks. Each pair is beaded across the sole and displayed casually, hanging from a pair of construction nails. During our conveyor-belt sushi outing, I asked Murray if she thought that her sock series was a kind of beginning. “Pair of Socks” (2017) was one of the pieces included in Murray’s BFA graduate exhibition and was the Saskatchewan winner of the BMO 1st! Art Competition. She responded with a measure of ambivalence, admitting “I think it’s what I’m kind of known for.”

We talked about the knots of being known for something and how it affords name recognition in a sector that values predictability as much as it is fuelled by novelty. This is one of the least glamorous anxieties of art practice but one that Murray must contend with every time she continues to work through an idea. In some ways, she knows that an idea can and should have multiple iterations but repetition for the sake of selling work seems stifling, especially at this point in her practice. As the recognition of her work grows, the margin of error seems to shrink as multiple art systems make competing demands: work needs to be for collectors but also for the increasingly large institutions that she works with—appealing to curators, CEOs, journalists, and other artists in equal measure. On top of these external demands, Murray feels the pull of her own intellectual curiosity as well as her need to make critical interventions into multiple cultural spheres.

When discussing her beaded work, Murray is quick to make a distinction between beading as a traditional practice and how it’s incorporated within the context of contemporary art. She identifies her work with the latter, pointing out how the sock-works undermine the function of the object. Traditionally, beadwork has been used to adorn objects that have a utilitarian, social, or ceremonial function. Instead of beading works so that they can be worn, Murray is beading clothing because it was worn. By using many sets of socks across the series, Murray is engaging different relationships to the time and labour of the body that wore them as well as her own body that labours through beading.

Within the nexus of being known, building a career, and managing her usefulness to so many different people, it might be easy for the subtlety of work to be swallowed up by the needs of others. This is one of the many predicaments facing Murray and one that signals the waning of an emerging practice and the waxing of an established one. In these moments of transformation, it often seems like the only marker of change is the emergence of new types of problems.

To Make Smoke (2024), installation view at Mackenzie Art Gallery. Photo by Carey Shaw

In 2022, Murray was the first Indigenous Artist in Residence for the city of Regina. For this project, she led a group of Indigenous youth through the process of making beaded wall hangings—a project which continued her trajectory away from beading as adornment toward something more sculptural. As part of the residency, Murray created “what is above is mirrored below (day sky)” (2023) a beaded wall hanging that uses a blended image of two photos taken simultaneously in Regina and Lebret, a rural community North-East of Regina, by Murray and her aunt Janette (respectively). Amid the tangled proximities of the city, the local, and the land that underpins all of these distinctions Murray looked toward the sky for a different notion of connection.

There are two types of wayfinding that are particular to Regina: most barrings are given in reference to either a high school or the location of a closed business. While talking to people who grew up here, it’s common to hear something like “it’s by Winston Knoll” or “it’s across the highway from the old Costco.” To someone without implicit knowledge of the city’s grid, these prompts often feel like curious riddles designed to gauge one’s degree of belonging. Instead of reading them as shibboleths designed to exclude, I now understand the way in which they become useful the longer you live here.

Among the veins of connectivity that run throughout Murray’s practice, there is also a consistent thread of distance, withholding, and obfuscation. Having drawn from personal relationships in my own art practice, I can identify with this inclination. Murray has made work in relation to her mother, brother, mooshoom, and son, as well as hammerstones and ancestral pieces of beadwork. Some of these works engage her relationship to ancestral objects at a distance, for instance through photographs like in the 2021 piece ‘chi fii embraces the old ones.’ In this piece Murray made a beaded daisy chain that she wrapped into the groove of a hammerstone, the work was then presented as large-scale photo-banners. She has told me about the discomfort she would feel placing these actual objects in systems of display that have been used to “other” Indigenous people and present them as specimens. The actual objects remain with her while the gesture is presented to the public through the distance of a photograph.

This urge to care for her relatives in institutional spaces extends to the work in To Make Smoke which problematizes the ongoing attitude that positions Indigenous identity as another resource to be extracted, processed, packaged, and sold. The irony of making these gestures in an exhibition sponsored by the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) and presented at an institution like the Mackenzie Art Gallery is not lost on her.4 Sitting in her studio, we talk about the forces of critique and collusion. On paper, they appear to be at odds but as institutional tastes turn toward normalizing issues of social justice and decolonization it seems harder and harder to tell where one begins and the other ends.

There is an apocryphal tale of old Hollywood actresses being filmed through vaseline-smeared lenses to give them a glow of soft focus. In the video “Bear Smudge” (2022) Murray uses bear grease to obscure the lens in this performance-for-camera, engaging a very different mode of representation. Though the resulting image is an abstract blur of colour, it holds the memory of petroleum jelly as a useful type of obfuscation. The action was also recorded as a cyanotype spread out on the ground on which Murray performed. Various objects used in the performance were recorded as shadows on this large piece of canvas which also holds the incidental prints made by the bear grease on her hands.

These oblique records perform a gesture of counter-archival consciousness. They privilege the embodied experience of making over its documentation—an act that seems apt in a time where gallery exhibitions are more like staging grounds for documentation rather than venues for experience. This process also affords the artist a space of mediated presence where certain aspects of her practice are kept close because they are private, and perhaps, not hers to share with the broader public. This mediation is an important part of artistic practice. Figuring out what to show and what to hold back is part of an editorial process but also part of caring for one’s self and in the case of Murray’s work, caring for a body of knowledge and experience which is held communally. There are parts of her work that are important to gesture toward but ultimately refer to cultural practices that exist beyond her personal authority.

It can be challenging for an audience to digest acts of refusal as pro-social behaviour. I think that sometimes it feels a bit too much like rejection but like many children of divorce, I try to see these boundaries as gifts and as a type of knowledge. In the words of Simone Weil: “The world is a closed door. It is a barrier. And at the same time it is the way through. […] Every separation is a link.”5