A journal for storytelling, arguments, and discovery through tangential conversations.

Wednesday, February 25, 2026

|

Emily Zuberec

The day after the opening of her solo-exhibition, Primary Information, I met Julia Dault in the basement 'Bunker' at Bradley Ertaskiran—a space that she specifically requested for her third presentation at the gallery. There's a certain drama to the room, given the mass of concrete, visible rebar, ventilation ducts, and amalgam of building material that cover the walls, like mineral deposits from preceding epochs of use. There we sat, shoes off, cross-legged on the most uncannily-coloured carpeting I've ever seen—not quite sulphuric, nor mustard, but somewhere between the two on the binary of fertilizer and food.

The colour of the carpet wasn't planned ahead of time, as the massive quantity was repurposed, and yet, its presence doesn't feel accidental, either. This is no doubt due to the material sensitivity that lies at the core of Dault's practice. Across her career and through the various disciplines she engages with—sculpture, painting, and, more recently, public art—there is a recurrent lightness of touch and precision of treatment, stemming from a keen awareness of the affective dimensions of the materials she engages with.

Monday, February 23, 2026

|

Hannah Strauss

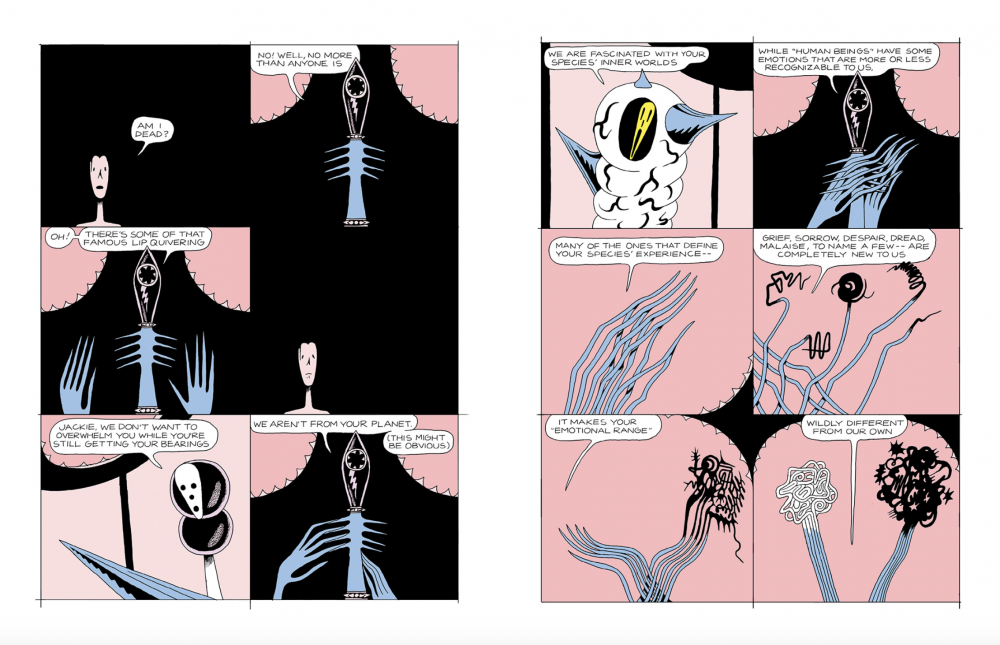

It’s thanks to the conversation with Michael DeForge transcribed below that I end up on YouTube reading the featured comments on an abridged audiobook version of Whitley Strieber’s alien abduction memoir Communion: A True Story. Philippe Mora’s 1989 film adaptation of the same name, Communion, is one of two central inspirations DeForge cites for his most recent book, Holy Lacrimony (2025). What makes the film so compelling, DeForge says at one point in our interview, is that it “sidesteps whether or not the experience is real,” in favour of taking seriously the material consequences of the protagonist's experience—in this case, of alien encounter. I would say this, too, is what all of DeForge’s books do with the experiences of their characters, not least Holy Lacrimony with its aliens, and it makes them similarly compelling. The books are less interested in what is plausible, or normal, or even what’s right, and more interested in what social and political outcomes an act might produce, even those acts performed in private.

Thursday, February 19, 2026

|

Sophia Lapres

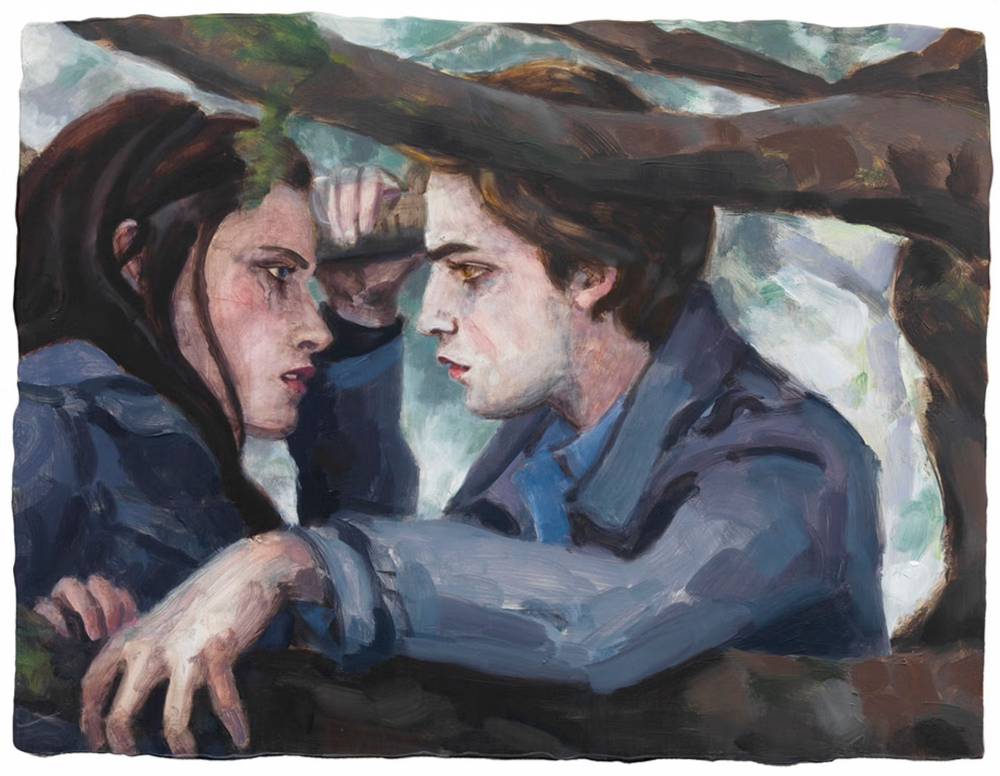

We grew up with our tongues pressed so hard against our cheeks, it’s no wonder we all needed braces. That’s a title for one of my own paintings: a couple kissing against a violently green background. I used the kiss between Drew Barrymore and her costar in the 90s film Never Been Kissed as a reference but it really could be any B-movie kiss, and that’s the point.

A writer whom I admire, and frankly have a bit of a crush on, lent me a monograph about the painter Elizabeth Peyton. A review by Roberta Smith contextualized Peyton’s cringingly sincere, fan girlish portraits of the recently deceased Kurt Cobain, invoking Realism, Karen Killimnick, and the Pre-Raphaelites. She diagnosed the portraits as part of a 90s trend toward “emotionalism,” an excellent description that never really stuck. I’ve been thinking about this review a lot. And I haven’t returned the monograph.

1—Most basically, Emotionalism is a genre of art: paintings, photography, film, and literature, etc….

2—Emotionalism is sticky, tinted pinkish red. It attracts wasps.

3—Emotionalist works all share a mood; a frank sentimentality.

Tuesday, February 17, 2026

|

Doreen Nicoll

John Brady McDonald is from the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation and the Mistawasis Nehiyawak. He is the great-great-great grandson of Chief Mistawasis of the Plains Cree who was considered a visionary leader and the first signatory of Treaty 6 in 1876.

McDonald is also the grandson of famed Métis leader Jim Brady, who is generally considered one of the most influential Métis leaders and activists in Saskatchewan and Alberta of his time. Brady disappeared while on a prospecting trip in June 1967. His body has yet to be recovered.

Forced to attend the Prince Albert Indian Student Residence in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, from 1984 to 1989, McDonald has served as an activist and advocate for fellow residential school survivors.

The Nêhiyawak-Métis musician, playwright, actor, speaker, author, and visual artist discusses how his lived experience comes through in all facets of his creative work and life.

Thursday, February 5, 2026

|

Gonzalo Reyes Rodriguez

In her 1988 song, Simplemente Amigos, Ana Gabriel belts out a confession disguised as restraint. It’s about a love that must exist in the shadows, spoken through a secret code of gestures and glances. The ballad moves between longing and endurance, mapping the tension between desire and secrecy. Similarly, Reynaldo Rivera’s photographs translate the impossibility of public love into forms of tenderness—where desire becomes both memory and a way to exist otherwise.

His Los Angeles is not the one full of celebrities, beaches, or Hollywood films that usually comes to mind. Rivera’s images depict a Los Angeles rarely shown. His photographs blur the line between the personal and the political, becoming indispensable records of a world both luminous and precarious. His portraits of performers, friends, and lovers capture a community that built itself through art, nightlife, and kinship at the edges of visibility.

Tuesday, February 3, 2026

|

Emma Cohen

When you’ve been living on, or with, the internet for over a decade, it can be difficult to recall your first encounter with a writer that you’ve become closely acquainted with over the years. When that first encounter isn’t a book—but an essay, conversation, or even simply a diffuse involvement in a certain school of online writing—it absorbs into the larger web of your own personal internet ecosystem. I thought my first brush with Larissa Pham was when I read her essay Crush in The Believer, but upon revisiting it, I found it was only published in 2021, and it feels as though I’ve been reading Pham for much longer. “I know and have worked with a lot of Canadians,” Pham told me when I voiced this sensation to her. She cited proximity through the years to essayist and critic Haley Mlotek, for example, and having written for the short-lived but stunning Adult Magazine, run by Sarah Nicole Prickett. “We probably have some overlaps,” Pham said. These moments of overlap are really a sign of communion: of mutual interest or even fixation on certain works of art and the writers who write about them. And for Pham, one thread of interest is precisely this sensation of communion over art.

Wednesday, January 28, 2026

|

Nic Wilson

I once heard a biblical scholar say that the Bible is much more like a library than it is a single book. Its polyphony is the result of many writers and translators creating branching paths along interlocking bands of narrative, guidelines, genealogies, songs, laws, histories and parables. It represents the shifting textures of religious thought as they have been shaped by time and circumstance. It is a raft of contradictions and tangents. It is a compendium of drift and change. The codex currently distributed by the Gideons is constituted as much by what has been edited out or lost as much as it is by what remains on the page. It is a well used library.

Unlike the narrative mess of the Bible, Western views of the past tend to assume history as a comprehensible, narratively consistent whole. In this view of knowledge, remainders are rounded off and doubts are often squashed when they disrupt a thesis or are relegated to endnotes. In the work of Calgary-based artist Lyndl Hall, ideas, shapes, and histories have scattershot points of articulation which often run counter to the assumed wholeness of history. With enough data points one can imagine a whole— but this view always comes with the need to squint or view from a distance.

Tuesday, January 20, 2026

|

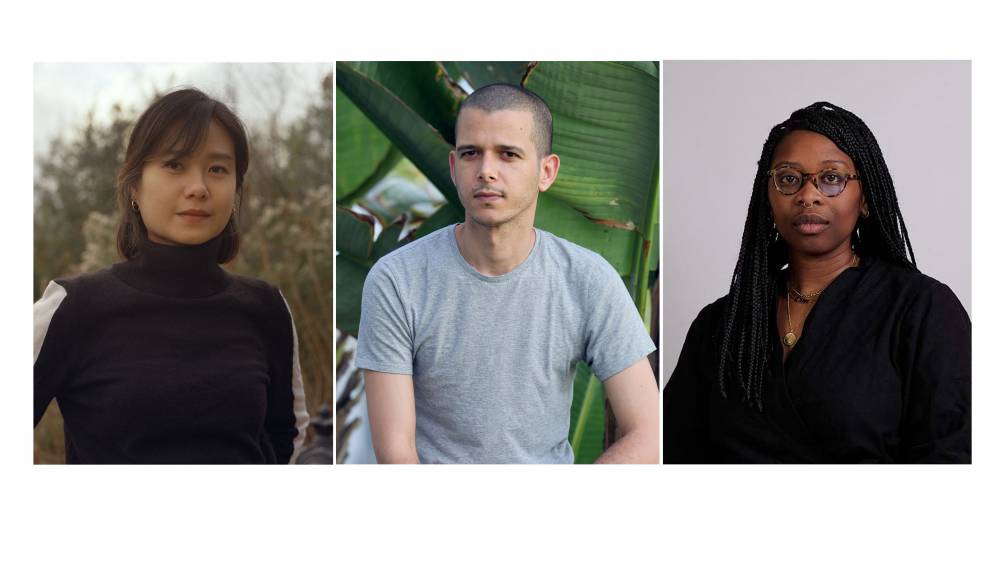

Public Parking

Public Parking Publication is delighted to announce the participants in our 2026 editorial residency. For this program, we aim to work with thinkers who are adjacent to or outside the realm of the arts as part of Public Parking’s ongoing efforts to broaden the scope of ideas we feature and the communities we reach. This project invites guest editors to serve as residents of the publication for an extended 12-month period. Throughout this time, they will work with our team to publish a series of texts, either self-written or in collaboration with other writers of their choosing. Previously, we've hosted eunice bélidor, Tammer El-Sheikh, Amy Fung, Nasrin Himada, and Shiv Kotecha.

Monday, January 19, 2026

|

Angel Callander

In August of 1945, the friendship between avant-garde filmmaker Maya Deren and writer Anaïs Nin turned into a nasty feud. Deren immortalized the clash in a poem dedicated to Nin:

"For Anaïs Before the Glass

The mirror, like a cannibal, consumed,

carnivorous, blood-silvered, all the life fed it.

You too have known this merciless transfusion

along the arm by which we each have held it.

In the illusion was pursued the vision

through the reflection to the revelation.

The miracle has come to pass.

Your pale face, Anaïs, before the glass

at last is not returned to you reversed.

This is no longer mirrors, but an open wound

through which we face each other framed in blood."

Their relationship had initially blossomed as neighbours in Greenwich Village and they eventually became collaborators on the basis of their shared interests in self-reflection and living their lives as artistic experiments. The rupture between the two occurred because of their opposing views on postwar aesthetics, namely how new technologies would impact the psychology of individuals, and artistic production in turn. While Nin preferred narcissism as an artistic strategy, obsessively writing diaries in hopes of discovering deeper truths about herself, Deren opted to experiment with techniques of self-recognition, believing that narcissism was a failure to consider oneself amidst external conditions.

Friday, January 2, 2026

|

Aidan Chisholm

Parasocial. Rage Bait. Vibe Coding. 67. Slop.

Each of these terms has been dubbed “word of the year” by a major dictionary. All originated online, went viral, and spread offline, entering the parlance in a way that would have been unimaginable, say, fifteen years ago. While the very selection of “67” might well be “rage bait,” this glossary captures a year of epistemic exhaustion in which intimacy has been streamlined, outrage optimized, production accelerated, and signs stripped of signification within ever more opaque digital infrastructures. “Slop” might, in fact, sum it all up. Fungible and frictionless, slop is the low-quality AI-generated content that has flooded feeds this year. Selected by both Merriam Webster and Macquarie Dictionary, the term captures the logic of oversaturated systems geared toward mindless consumption.

From this linguistic smattering, at year’s end, looking back on 2025, what comes to my mind is: “surreal.”

Monday, December 29, 2025

|

Abby Maxwell

The secret’s out: Canadians are feeling bad—and there’s something we all have in common. If the past few years have felt like watching this country wither and die, 2025 was lived from inside of Canada’s lifeless body.

From within the carcass of Canada and beyond, we are witnessing the collapse of colonial states—extraction projects that rely absolutely on racialized violence and ecological fallacy. Canada in 2025’s dusk is an open pit; its bones are exposed. Its skin is rotting. The nation is fantasy. What is true is this: when things fall apart, we begin to see what they are made of.

Friday, December 19, 2025

|

Nasrin Himada

A Smile Split by the Stars: An Experiment by Katherine McKittrick is an exhibition that brings m. nourbeSe philip's poem "Meditation on the Declension of Beauty with the Girl with the Flying Cheek-bones" into two gallery spaces. Co-produced by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Gallery 44 Centre for Contemporary Photography, Revolutionary Demand for Happiness, and Modern Fuel Artist-Run Centre, the exhibition began with a conversation with Katherine McKittrick—Professor of Gender Studies and Canada Research Chair in Black Studies at Queen's University—during a rideshare in Kingston on our way back to campus where Katherine shared with me her love for the poem.

Katherine is the author of Dear Science and Other Stories and the foundational Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle, as well as editor and contributor to Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis. Beyond her scholarly work, Katherine loves bookmaking and often collaborates with artist and designer Cristian Ordóñez, most recently creating the limited-edition boxset Trick Not Telos (2023) and the hand-made Twenty Dreams (2024). Ordóñez also spearheaded the exhibition design for A Smile Split by the Stars.

At the heart of this project is Katherine's approach to practice and scholarship. As she writes in Dear Science, "Seeking liberation is rebellious," emphasizing that the goal is not to find liberation, but to seek it out. This process of seeking, what Katherine calls "method-making," generates the gathering of ideas and creates space where we can feel possibility together.

Wednesday, December 17, 2025

|

Lodoe Laura

I first met filmmaker Kunsang Kyirong last summer at my friend’s coffee shop in Roncesvalles—the Toronto neighbourhood halfway between my apartment at Bloor and Dundas, and her place at the time in Parkdale. When we met, she was in post-production for 100 Sunset—her first feature-length film.

Born in Vancouver, Kyirong studied 2D+Experimental Animation at Emily Carr University of Art and Design, and is currently pursuing her MFA in Film Production at York University. Her previous short films Dhulpa (2021) and Yarlung (2020) have been screened at various international film festivals and exhibited at The Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art.

Kyirong told me about her newest film, which she centered around a relationship between two young Tibetan women living in Parkdale. The neighbourhood, which is also known as Little Tibet, has long been one whose landscapes are shaped by the Tibetan-Canadian community. For those of us who have spent time in the diaspora, it evokes a familiarity built on proximity, community, and the rhythms of daily life lived in close quarters.

Tuesday, December 9, 2025

|

Claire Geddes Bailey

For the past three-and-a-half years, the garage behind 903 Lansdowne has been home to Joys, an independent gallery operated and initiated by writer and curator Danica Pinteric. Accessible by the laneway between Lansdowne and St. Clarens, the gallery’s entryway is marked by its iconic arched door and—most Saturdays—the presence of Pinteric, awaiting visitors. With a curatorial style as incisive as it is intuitive and process-driven, Pinteric’s mark on the city has been lively and thought-provoking, emanating a particular poetic quality. As a poet myself, perhaps what draws me to Pinteric’s work is how she borrows the techniques of poetry in her curatorial practice. Playing with iteration and repetition within and across exhibitions, Joys’ programming has a sense of rhyme and rhythm. Working at the meeting-point of precision and feeling, abstraction and clarity—the frequent wheelhouse of poets—the impact of Pinteric’s approach is felt both through the quality of the work she presents and the community that surrounds Joys.

Monday, December 8, 2025

|

Lizzie Derksen

As a teenager, I taught myself to write with my non-dominant left hand. My penmanship became legible if not elegant. I liked the different poems that emerged. Nevertheless, once my identity calcified post-pubescence, I gave up the practice for 17 years—until I started writing with my left hand while breastfeeding my first child.

Once again, I can feel hesitant new neural pathways forming. Once again, I am surprised by what I write, and by what it says about who I am becoming.

A few weeks after my son was born, I read Lucy Jones's book Matrescence, in which she cites a recent study showing that the brain changes undergone by biological mothers are comparable in scope and consequence to the brain changes commonly associated with puberty:

“The group compared the brains of twenty-five first-time mothers with twenty-five female adolescents; the brain changes were extraordinarily similar. Each group had reductions in cerebral grey matter volume at the same monthly rate. Both showed changes in cortical thickness and surface area, and depth, length and width of sulcal grooves (the lower part of the Viennetta-like ripples of the brain).”

Though this study was small, it confirms Jones’s—and my—subjective experience: Like teenagers, new mothers are engaged in a dramatic, intensive identity-forming process.

Thursday, December 4, 2025

|

Marcus Civin

An algorithm didn’t bring me to Muscle Man, Jordan Castro’s satirical, foreboding new novel about wayward English professors, but it could have. I’ve worked and taught in colleges since completing my master’s degree in the late aughts. I recently binged The Chair (2021) and Lucky Hank (2023), somewhat formulaic shows about academics and their departments coming comically undone. Muscle Man is funny at times. It’s also tense and much less predictable than the typical departmental drama. The central character, Harold, recalls feeling optimistic early in his career, thinking of himself as a priest in a temple of knowledge. “He had been excited to break free from the confines of society, and to enter into communion with the great thinkers of history,” Castro writes, “Academia promised a glimmering future, one in which worldly concerns were secondary to the pursuit of what he then viewed as higher ambitions.” When we meet him, though, Harold finds even the college architecture oppressive. He’s isolated. He doesn’t get along with the students or most of his peers. On the single day that the book takes place, his ears are ringing. In the hallway, he observes the bodies and faces around him as horribly misshapen, threatening to destroy him, and making sounds he doesn’t understand. “Limbs stretched over everything like unspooled yarn, mouths and walls making the same sad sound, a kind of scream-yawn, obliteration song…”

Wednesday, December 3, 2025

|

Ioana Dragomir

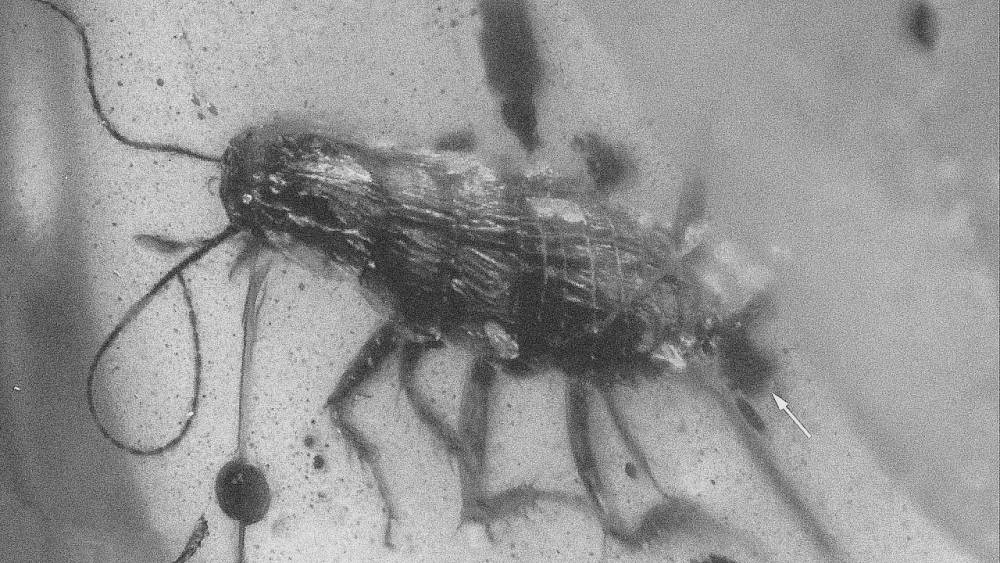

By the time my landlord emailed me to schedule an inspection with the exterminator to determine the severity of the cockroach infestation in my apartment, I had already been thinking about them for months. There were no signs yet, not really. Later there would be moments when I would pause whatever I was doing, breathing in through my nose like a gross gourmand in an attempt to determine if the scent I was smelling was just a symptom of living in close proximity to other people, with open windows, drafty doors, and thin walls, or the telltale sweet musk of an intrusion of cockroaches.

During the exterminator’s first visit, he asked a few questions and looked around. No, I had not seen any cockroaches at night when I got up to go to the bathroom. The results of my sniffing were inconclusive. I had seen no cockroach droppings but also, I had no idea what those looked like. What I didn’t tell him was that during the summer, I had become obsessed with a novel by Clarice Lispector called The Passion According to GH, in which nothing much happens. A woman, having recently lost her maid, goes into the servants’ quarters to find a cockroach half-squished by a wardrobe, and spends a hundred-some pages contemplating it and the various expansions and contractions of the moment it represents. Ultimately, she licks it.

Monday, December 1, 2025

|

Yannis Guibinga

I have always known Mallory Lowe Mpoka to be an artist who refuses to be limited by one medium. Her work presents her ideas through a unique artistic perspective and visual language, seamlessly merging image-making processes, textile, and ecological material. The result is something entirely new and incredibly interesting.

Presented during the MOMENTA Biennale de l’image 2025 in Montréal, The Matriarch: Unraveled Threads marks the first solo exhibition of the Cameroonian-Belgian multidisciplinary artist. Working across diverse mediums, Mpoka’s practice explores the material and emotional landscape that continue to shape diasporic identities across and beyond the African continent. At the center of the exhibition stands a monumental textile installation composed of over 300 screen printed panels of recycled linen and cotton, dyed with the red soil from Cameroon. That piece—which shares its name with the exhibition—is a perfect representation of Mpoka’s artistic practice and her ability to push several artistic mediums forward simultaneously, while anchoring it in archives, heritage and family history. Although her practice previously focused on the technicality of photography, she has since expanded beyond the bidimensionality of the traditional photographic frame to tend to processes of repair and collective healing. Through weaving, ceramics, dyeing and sculptural augmentation, Mpoka engages the body, the soil and the self as living archives.

Thursday, November 27, 2025

|

Sabrien Amrov

TORONTO 2024 — At the Dinner Table:

“Watch out for your hate, you do not want it to turn into what happened to Jewish people in Europe.”

These words are uttered by a friend after I share that lately I have been carrying a sense of enmity towards Israel. My good friend and I are sharing a meal on the carpet of my overpriced rented studio apartment. We are in Toronto, a city with barely any redeemable qualities, to me, a Montrealer by way of Palestine. After spending close to a decade in the city-state of Istanbul, to me, Toronto is a godforsaken place. But since the violence of genocide began on October 7, my loathing for the city has been eclipsed by a bottomless grief, and increasingly, a sense of enmity—rage of seeing my loved ones disappear in a live-streamed genocide. Witnessing the collective annihilation of family and kin seeds something in my insides, and I want to let it out to a friend.

I offer the word enmity, but she keeps defaulting back to “hate.” I tell her that hate is not a term I work with. In Canada, “hate” is taught to us in schools as an irrational emotion that comes when a person has a hard time with differences. In the North American vernacular, “hate” is often dealt with in an a-contextual, a-historical fashion. It is this thing that you either hold or do not. She offers advice to focus “on love rather than hate” because there is something ugly about enmity.

Tuesday, November 25, 2025

|

Conor Williams

A few nights ago, I went to a screening of Letter to Jane, the 1972 essay film by Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin. Speaking with the audience over Zoom after the film, Gorin said, “There used to be critics.” He recalled how, in the 60s and 70s, filmmakers could actually be in dialogue with others about their work. “Today, the only critic I can think of is A.S. Hamrah.”

For several decades, the writer A.S. Hamrah has contributed to publications like n+1 and Bookforum. His criticism is laser-focused, unfazed by the soft language used all the time by corporately owned entertainment outlets. Hamrah has the unique and so-needed skill of being able to dispense with bullshit entirely. He’s frank, and very funny.

It’s great news, then, that Hamrah has two new books out. The first is Last Week in End Times Cinema, a printed version of his online newsletter, “an almanac of every bad thing that happened in the film industry from mid-March 2024 to mid-March 2025,” (Semiotexte). Formatted just like the original email publication, End Times Cinema sticks to the basics.

Monday, November 24, 2025

|

Michel Ghanem

From Zero Dark Thirty to Homeland and news reports, Afghanistan is frequently depicted through a familiar visual and auditory vocabulary: fast-paced shaky camera footage, violence and chaos, torture, and the markers of breaking news. In the Room, a documentary that premiered at the Vancouver International Film Festival in October, pierces through with a gentler approach, subverting expectations. Early in the festival, director Brishkay Ahmed and I met over Zoom for a 40-minute conversation about using sensory memory and reenactment to tell this story, her profoundly moving on-screen conversations, and how the struggle of Afghan women is intertwined with the rest of the globe. One thing is very clear from the documentary: This is not a breaking news story, and Ahmed—who has directed numerous documentaries, films, and written plays—worked to avoid those aesthetics completely. “I did not want it to look like breaking news. I didn’t want it to have that palette,” she told me.

By placing herself in front of the camera in the film, In the Room becomes as much an autobiography of Ahmed’s coming-of-age and embracing of her identity in Vancouver as it is a weaving of five Afghan women’s stories leading up to August 2021, when the Taliban seized control of the Afghan government.

Wednesday, November 19, 2025

|

Gladys Lou

Hundreds of phones, tablets, and video projections flash in dissonance. Water cascades over touchscreens, tapping, swiping, and scrolling through websites and apps. This endless flow of information animates the hypnotic whiplash of Yehwan Song’s multimedia installations. A Korean-born, New York-based web artist with a background in UX/UI design, Song stages dystopian fantasies of the digital world that subvert the notion of “user-friendly.” Saturating screens with fragmented images of her own body, Song leans into glitch aesthetics (or glitches), seeking out the loopholes and flaws that most interfaces work to conceal. Through immersive installation and interactive performances, Song hacks the design logic of machines, tinkering with her websites, videos, and sculptures to expose the hidden infrastructures of digital systems.

While Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto (1985) imagines a fluid entanglement of human and machine, and Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism (2020) considers error and disruption as acts of resistance, Song mobilizes these ideas in the everyday mechanics of the internet.

Thursday, November 13, 2025

|

Leo Cocar

If there’s anything I have gleaned over the course of my engagement with the work of lens-based artist, Nabil Azab, it is that there is a liberatory quality in the act of denial. Azab’s approach to photography rejects the long-canonized idea that the photograph is a neutral documentation of truth, or of the world “as it really is.” Azab’s approach is an eschewment of the idea that the photograph has to of anything recognizable—a refusal of the notion that the poetic quality of the photograph has to emerge out of an imagined naturalism, which operates as a stage for the interplay of recognizable signs and symbols. In short, it is a turn away from the photographic image as a kind of concrete language.In their practice, large-scale prints take up a painterly quality through a litany of means; from the use of ecstatic-impulsive snapshots, to repeatedly projecting and re-photographing archival images, and the use of over exposure. At a formal level, abstraction, monochromatic compositions, superimposed marks, and canvas stretchers make frequent appearances. On occasion, the subjects captured by Azab’s camera hover at the edge of discernability. In other cases, we are presented with surfaces suffused with varying washes of color bleeding into one another, calling to mind voices from the Color Field movement.

Monday, November 10, 2025

|

Irene Lyla Lee

When the biologist Charles S. Elton coined the term “invasive species” in his 1958 book The Ecology of Invasion by Animals and Plants did he know his language would change the imagination about the dangers introduced species could bring? Right at the introduction he eagerly elucidates a nightmarish vision: “It is not just nuclear bombs and wars that threaten us, though these rank very high on the list at the moment: there are other sorts of explosions, and this book is about ecological explosions.” And he goes on to describe the horrors of plant invasions (along with bacterial, viral, and animal). And so the fated comparison between a bomb and an overgrowth of plants was established.

Both climate change and globalization are factors that make interchange of species inevitable and fast paced, which can lead to situations where species negotiate space with each other in sometimes fatal encounters. It can’t be denied that invasive species are a global threat to biodiversity. However, being afraid of plants is not going to help the fact that they are moving all the same. In the United States, up to 1 billion pounds of pesticides stave off unwanted or aggressive plants and pests per year, yet invasive species grow on their own in a range of soils and conditions, and usually are nutritious or have value for textiles or building.

Wednesday, November 5, 2025

|

Chris Cassingham

In my experience, small film festivals geographically far-removed from the US often offer the most thoughtful curation of its cinema. With little, or even zero, pressure to cater to American studios and distributors, their programs function as a more adventurous barometer of the state of the nation than whatever Hollywood deems important enough to share with the public. I approached covering this year’s edition of the Paris-based documentary festival, Cinéma du Réel, with this in mind, excited for and open to unknown gems within its lineup of daring nonfiction cinema. My greatest personal discovery was the feature debut of Armand Tufenkian, In The Manner of Smoke (2025), a hybrid docufiction of sorts about the narrator’s experience working as a fire lookout in the forests of Central California, near Fresno.

Born to Armenian parents in 1988, Tufenkian completed his undergraduate studies at Colby College, his doctoral studies at Duke, and earned a degree in Film and Fine Arts at the California Institute of the Arts. “One of my teachers had this idea of living your life through cinema, and that really resonated with me,” Tufenkian told me over lunch in Brooklyn in late August. This philosophy of filmmaking—not merely intellectual and emotional, but participatory and immersive—has guided his career from the beginning.

Monday, November 3, 2025

|

Chukwudubem Ukaigwe

Camille Turner’s multi-modal solo exhibition Otherworld occupied the entire expanse of University of Toronto’s Art Museum, transforming architectures of space and time into labyrinthine configurations suggestive of both the brutal lived reality of transatlantic slavery and its afterlife, as well as its fabulated futures. This liquid-like exhibition, curated by Barbara Fisher, mobilizes oceanic poetics, and calls for a poetic response, as prosaic prose falls short translating its fluid permutations.

Beyond breaking this essay into three parts to aid contextual submersion, I will lace my response to this exhibition employing an errant method of building synapses of thought, attempting to correspond to the artist’s conceptual derivations and approaches. Turner’s research-based practice affords and invites such analysis. In addition to the Afronautic Research Lab—a table displayed with evolving print metadata that exposes and probes the historical complicity of what is now Canada with the Middle Passage—expansive artwork labels synopsize details of historical contexts that each piece builds upon. Nearly all the video works are appositely titled after actual slave ships built in Newfoundland, Canada.

This essay unpacks Turner’s method for producing speculative work from archives—as a tool that envisions the future by revisiting the past—and the myriad ways her work manifests in the contemporaneous. Turner’s collaborative approach, how she problematizes linear time; both planetary and geologic, as well as how she mobilizes material through an interdisciplinary lens with phenomenological implications, both spatial and affect intact, will be highlighted. I will conclude this essay by exploring the role of the transatlantic slave trade in shaping finance capital and our currently disconcerted world order.

Wednesday, October 29, 2025

|

Aidan Chisholm

Urine is to be flushed and forgotten, concealed through elaborate infrastructures that buttress modernist fantasies of the human body as a sealed-off and self-contained vessel untainted by waste. And yet in the disavowal of the messy by-products of embodiment, these very systems attest to the transgressive threat of bodily fluids, which expose the ultimate limitations of control.

Urination—like defecation, perspiration, regurgitation, ejaculation, and lactation among other subtle and less subtle mechanisms of release—constitutes a mundane performance of corporeal porosity. Breaching the illusory boundary of the skin, urine evokes the necessarily dynamic constituency of ecologically enmeshed bodies. The slippery ontological status and the unruly materiality of urine render the substance particularly ripe for artistic inquiry.

Monday, October 27, 2025

|

eunice bélidor

Frantz Patrick Henry and I met in the Spring of 2019. I co-curated the exhibition "Over My Black Body" at Galerie de l’UQAM with my friend Anaïs Castro. Stanley Février, one of the artists in the show, had a team of assistants supporting him, of which Patrick Henry was a part. I had to engage in numerous back-and-forth discussions at the gallery regarding exhibition design, setup, lighting, and the artists’ well-being. His attention to detail and calm demeanour were more than welcome as the opening date was approaching. I followed his career since, noticing every time that there was something distinctly Haitian about his work: his use of found objects, the blending of many life forms, his use of metal and stone, and the painterly composition of his installations reminded me of the artists I have studied and have encountered in my relatives’ homes. Still, Frantz’s practice strikes me as one that is rooted in thoughts and gestures that stem from meticulous research on a vast set of interests and affects that always situate his work in a Global context.

Wednesday, October 22, 2025

|

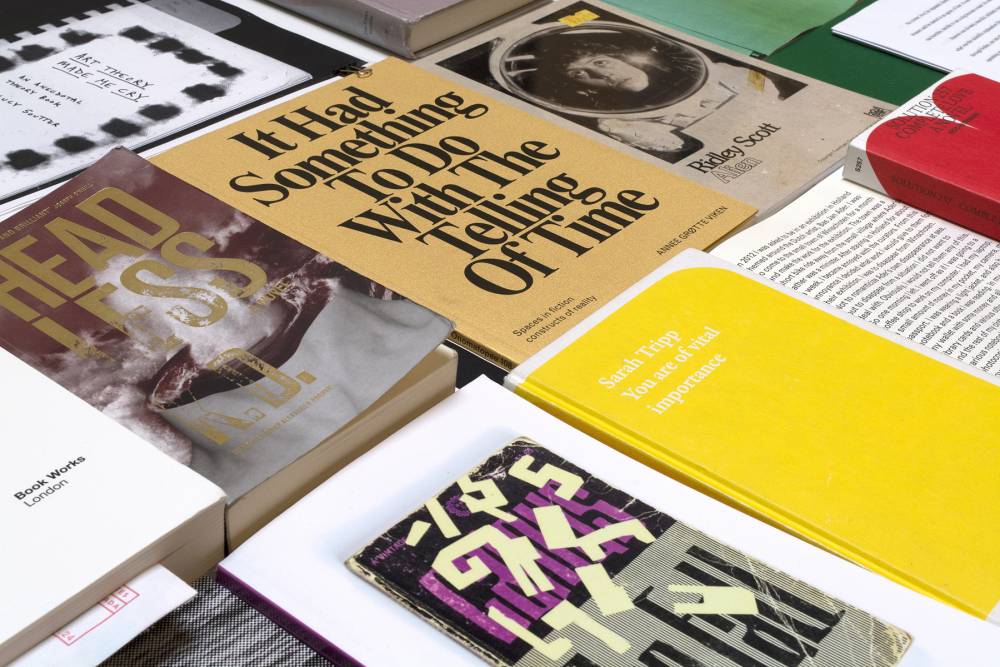

Nic Wilson

Over the last decade, I’ve had many conversations with peers about why artists’ publishing seems to remain so niche, especially in the landscape of Canadian contemporary art. It’s rare to see artists’ books in gallery settings and rarer still to get access to museum libraries. It’s almost unthinkable that an institution might offer a free book as part of its programming. These are by no means impossibilities, but they remain isolated experiences amid the overwhelming majority of exhibitions which tend toward more traditional art objects, performance, and video. Throughout my practice, questions of ontology in art-making have emerged and receded, but the question of where books belong in an arts ecosystem continues to spark contemplation and confusion for me.

Part of this confusion stems from the fuzzy task of definition—one that feels more like assembling a raft of exceptions rather than a list of declarations. In my experience, the artist’s book can be clumsily analogized thusly: any type of book in the visual arts can be an artist’s book but not all books in the visual arts are artist’s books. They can be published in conversation with other works but they are usually not documents of exhibitions; they are works in and of themselves (as much as an artwork can ever be considered a discrete unit). There is no prescribed way of producing an artist’s book. They can be singular, handmade objects or mass produced in ways that make them almost indistinguishable from other commercially produced books. They can be made in traditional printmaking studios or at a municipal library with laser printers, scissors, and tape.

Monday, October 20, 2025

|

Nicolas Vamvouklis

Philipp Timischl has built a practice on making artworks that behave less like static objects and more like characters in a play. Born in Austria in 1989 and now based in Paris, he works across painting, sculpture, video, photography, and text, collapsing distinctions between media to create installations that feel at once theatrical and oddly intimate. His pieces often stage encounters with power—whether tied to class, queerness, or the structures of the art world—while remaining disarmingly playful in tone.Timischl’s path into art was shaped by studies at the Städelschule in Frankfurt and the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, institutions known for producing artists eager to test the boundaries of medium. From early shows at Halle für Kunst Lüneburg (2016) and Secession in Vienna (2018), through to solo exhibitions at MGK Siegen (2023), Le Confort Moderne in Poitiers (2024), and the Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade (2025), he has steadily built a reputation for turning the exhibition itself into a stage.