Breath feels like a person’s most immediate form of need. Water and food can wait and intervals between pissing or shitting can be measured in hours but breath is so essential it hangs at the periphery of consciousness. The conscious mind can dictate these intermittent needs. You can forget to eat and even choose to starve but breath is much more slippery. If you forget about it you still maintain a breath pattern but if you start to think about it you can fool yourself into believing you might never take another unconscious breath. Unlike blood flow or digestion, which one has little to no conscious control over, breath can be held strategically (while swimming in water or escaping a house fire) or become a tool. You blow out the scented candle the way some distant ancestor blew pigment onto a cave wall to capture the negative space of their hand. In the Bible, God creates Adam out of dust and breathes life into him through his nostrils. Breath has been used as an essential signifier of human life itself. Along with keeping us alive, it connects us to the lungs of people around us; a sometimes unbearable intimacy especially after 2020. That year, unlike many others I have known, the air became charged—politically, emotionally, economically, environmentally—like the gasses in Earth’s upper atmosphere when the Sun’s radiation shoots through it, triggering the glow of the aurora.

In Open Structure, mounted at the School of Art Gallery at the University of Manitoba from November 2022 to January 2023, air takes on a malleable materiality. Throughout the exhibition, visiting curator Grace Deveney orchestrates the work of eight artists (Ron Bechet, Jared Brown, Whit Forrester, Jennie C. Jones, Harold Mendez, Janelle Ayana Miller, Kameelah Janan Rasheed, and Derrick Woods-Morrow) finding harmonies and dissonance in a way that recalls the harmonic structure from which the exhibition takes its name. In Western music theory, an open structure describes a chord in which there is more than an octave between the top and bottom notes.

Along with this interpolation from music theory, Deveney1 and the artists in the exhibition mobilize the history of Black avant-garde music to think about the ways that one might find resonances across different times and disciplinary boundaries. Outside the main gallery space otherwise (2021), a video by Kameelah Janan Rasheed, silently presents footage of figures like Nina Simone and Gil Scott-Heron layered with text. These fragments of language are presented as subtitles emphasizing the communicative nature of breath. The words “[Emotional Breathing]” are paired with footage of Simone performing her 1964 civil rights anthem “Mississippi Goddamn.” This pairing signals the potential of breath to hold meaning that, while unspoken, remains available for a viewer—especially when paired with the possible recollection of Simone’s words: “Can’t you see it/Can’t you feel it/It’s all in the air […] Everybody knows about Mississippi Goddamn.”

Derrick Woods-Morrow. How do we memorialize an event that is still ongoing?, 2022, used mattresses, various natural stains, subwoofer, wake work.

Many exhibitions are staged in half-empty galleries but that negative space sometimes seems to stand in for curatorial intention—the way that line breaks can signify ‘poetry,’ even if they are entirely arbitrary. In Open Structure, the spareness implied by the title felt like it was leaving space for an attentive viewer to recognize a whole range of possible harmonic resonances. The exhibition responds to spaces that are sometimes considered empty or irrelevant like the air in the gallery, the acoustics of the space and the reflective quality of the polished concrete floor. The work in the exhibition highlights the charged nature of these spaces and espouses a subtle but insistent political urgency. Throughout the exhibition, Deveney and the exhibiting artists consider the ways that elemental experiences, like that of electricity and the physical force of sound, can take on unexpected social, emotional, and historical dimensions.

Upon entering the space, I was immediately confronted by a twin mattress standing on end like a tombstone or a monolith. Entering into the space of How do we memorialize an event that is still ongoing? (2022) by Derrick Woods-Morrow, you can hear the rounded edges of Blow by Moneybagg Yo radiating from the mattress which vibrates in time to the beat of the song. The surface of the mattress shuttered like laboured, frantic breathing. I thought the mattress appeared to be having a nightmare. I stood close to the mattress and felt the radiation of sound in my chest. I was reminded of the large speakers that are suspended from the ceiling of music venues and the volume of air they push out into the crowd.

I was initially drawn to live music because of its physicality. I remember standing in front of speakers the size of Woods-Morrow’s mattress as a teenager. Thick bands of compressed sound were pumped into my body by these monolithic speakers and I was transfixed by the euphoria induced when you are immersed in extremely loud sounds for an extended period of time. People I played in bands with called it being “noise drunk.” Though the tender intimacy of sound was my first thought, my encounter with the weight of sound in Open Structure also brought to mind the US and UK’s torture of Iraqi prisoners of war by playing Metalica and Eminem for hours at earsplitting volumes.

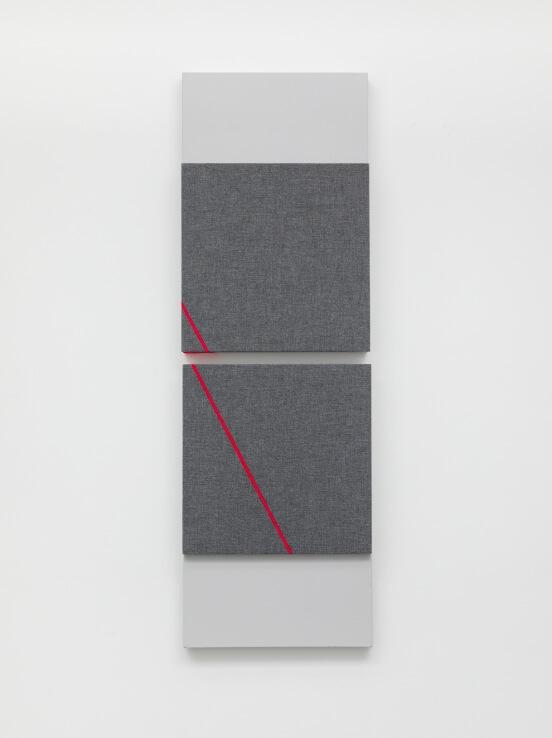

Turning around, I encountered Vertical Shift, Fractured Crescendo (2019) by Jennie C. Jones which brings the acoustic panelling of recordings studios into the realm of Minimalist abstraction. These panels are used to soak up sound in recording studios and the How do we memorialize an event that is still ongoing? and Vertical Shift, Fractured Crescendo seem to be placed in a symbiotic relationship where one performs and the other witnesses. Across the surface of Jones’ panels, a red line bisects each rectangle, bringings with it another set of twinned associations. When recordings are “pushed into the red” the sound overloads the recorder’s capacity and the signal begins to distort. Another part of the cloud of associations brought on by Vertical Shift, Fractured Crescendo is the practice of redlining. This system of racist mortgage and insurance schemes has blocked access to generational wealth for many people of colour in both Canada and the United States ever since it was introduced in the 1930s. This system labelled many predominantly Black neighbourhoods and suburbs as “high-risk” for mortgages and housing insurance, denying an essential piece of economic security. Economic inequity also ripples through the economic anxieties radiated by Woods-Morrow’s work when Moneybagg Yo says he “Talk about money all the time, I can't change the convo.”

Across the gallery, a large, bisected circle of gold sits like a sun hanging low on the horizon, casting its glow over the polished concrete floor and making the expanse of the gallery into an ocean. The Electric Universe Theory by Whit Forrester is an enormous work whose scale and shape recalls a rose window. Its position in the gallery reinforces this abstract connection to religious effect by meeting the viewer as they enter the space and presiding over the white cube from the back wall. Like many other works in the exhibition, it feels on the edge of association—like the space between mist and rain. Viewers were invited to touch the work and when I placed my fingers on either half of the circle, I felt a small sting as my body completed the circuit of an e-stim pumping a low-level electrical charge into the gold leaf. I found it amusing that this straightforward mode of tactility (the sense I associate most immediately with embodiment) seemed to be positioned so intentionally towards the realm of spiritual concerns and Christian religious traditions that routinely diminish physical experience as impure. I was even more pleased to see this accomplished with the aid of a sex toy.

Jennie C. Jones. Vertical Shift, Fractured Crescendo, 2019, acoustic panel, acrylic on canvas. Photo: Evan Jenkins.

Throughout the exhibition, other harmonic riffs challenge and compel my conceptions about living in a human body. Transformation by Ron Bechet is one of several monumental drawings that recall the scale of a starship view screen, bringing my body back to the earth. They depict a series of knotted roots and tree stumps from the vantage point of a person who is impossibly close to the ground. When confronted with their scale, I take a moment to think about the massive, global engine of oxygen production and carbon sinks that humans rely upon to regulate the transformation of carbon dioxide into breathable oxygen and the profound rate of its ongoing destruction.

Human bodies share in the contradiction of the Earth’s incredible capacity for regeneration as well as its undeniable vulnerability and fragility. Walking amongst the silences, pauses, and sharp inhalations of Open Structure felt like a generous catalogue of levitations. Like the space between notes in a chord or the vast echoes of a white cube the work, assembled with careful attention, pulls at potential meanings and pushes with magnetic force. As an exhibition, it was, at first, confounding and then evident—like the effects of radiation or the appearance of the Milky Way in the vastness of the night sky. Rather than bringing together work around a central theme, the exhibition takes a more porous approach, giving each work agency to turn on several axes providing a multiplication of possible meanings, rather than focusing on a convenient commonality between them. It is a generous invitation to find uncommon connections and resonances outside of one’s usual harmonic structure.