A journal for storytelling, arguments, and discovery through tangential conversations.

Thursday, February 19, 2026

|

Hannah Strauss

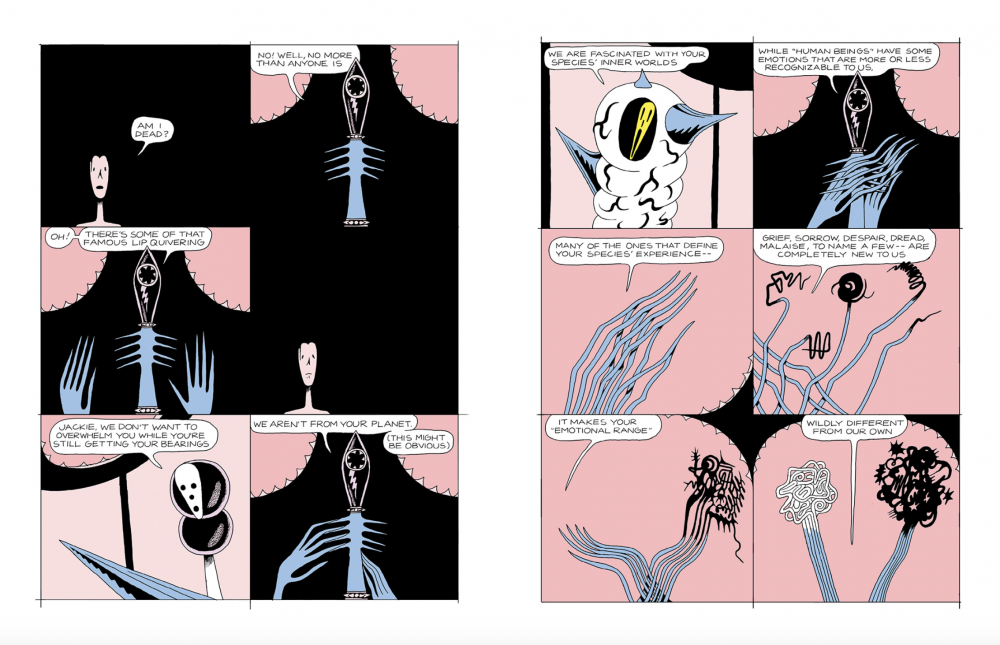

It’s thanks to the conversation with Michael DeForge transcribed below that I end up on YouTube reading the featured comments on an abridged audiobook version of Whitley Strieber’s alien abduction memoir Communion: A True Story. Philippe Mora’s 1989 film adaptation of the same name, Communion, is one of two central inspirations DeForge cites for his most recent book, Holy Lacrimony (2025). What makes the film so compelling, DeForge says at one point in our interview, is that it “sidesteps whether or not the experience is real,” in favour of taking seriously the material consequences of the protagonist's experience—in this case, of alien encounter. I would say this, too, is what all of DeForge’s books do with the experiences of their characters, not least Holy Lacrimony with its aliens, and it makes them similarly compelling. The books are less interested in what is plausible, or normal, or even what’s right, and more interested in what social and political outcomes an act might produce, even those acts performed in private.

Wednesday, June 4, 2025

|

Hannah Strauss

Almost twenty years since being introduced to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, a few of its pages still regularly come to mind. One panel in particular, in which a face is progressively whittled down to its simplest graphic form, two dots and a line, has really stuck with me. The narrator asks, “WHAT IS THE SECRET OF THE ICON WE CALL – THE CARTOON?” And in the next panel, “WHY - ARE - WE - SO - INVOLVED?” McCloud poses a question to the reader about why this brutally diminished form is still so “acceptable” to us – why, rather than estranging, it can open up a space for identification more immediate and reliable than one highly realized.

For those more widely read in the genre than I am, it might feel a bit reductive to open an interview with Walter Scott, the Kahnawà:ke-born, Tiohtià:ke (Montréal)-based interdisciplinary artist and author of the much-loved Wendy comics, with reference to McCloud’s classic introduction. But I thought about these panels while preparing to interview Scott, not just because he makes comics, but because his work foregrounds the genuinely mysterious capacity of caricature to both reduce and elaborate character. Scott’s figures and their attendant objects (or his objects and their attendant figures) capture simple being – for instance, the plainly apparent experience of misery, that infinitely non-universal universal. Simultaneously, they offer us characters nobody could fail to recognize as vitally specific, differentiated, subtly or not, by their particular features. I mean class, race, gender, but also eyebrows, shoes, or types of ambition.

Thursday, November 14, 2024

|

Hannah Strauss

Diyar Mayil is a sculptor who lives in Montreal and is originally from Istanbul. This is an incomplete list of materials found in her work: cherry wood, silicone, ceramic, salt, brass, battery-operated motor, latex, glass, gold, raw silk, aluminum, hair, velvet, satin, PVC, rubber. Most of her sculptures take the form of household objects and are titled to reflect this: “Dustpan”, “Medicine Cabinet”, “Mop”. They are tables, clocks, beds, brushes, books. Sometimes these objects get put into motion in performances. Although they are, in contour, ordinary objects, Diyar’s sculptures are designed to be weird: the mop is made of glass, a 10-foot-long wood and fibre brush sits on the floor of the gallery with the affect of a slug or a crocodile, a table’s fleshy palette makes it repellant rather than inviting. This push and pull between known and new, comfort and disturbance, is central to Diyar’s work and how she talks about it.