Diyar Mayil is a sculptor who lives in Montreal and is originally from Istanbul. This is an incomplete list of materials found in her work: cherry wood, silicone, ceramic, salt, brass, battery-operated motor, latex, glass, gold, raw silk, aluminum, hair, velvet, satin, PVC, rubber. Most of her sculptures take the form of household objects and are titled to reflect this: “Dustpan”, “Medicine Cabinet”, “Mop”. They are tables, clocks, beds, brushes, books. Sometimes these objects get put into motion in performances. Although they are, in contour, ordinary objects, Diyar’s sculptures are designed to be weird: the mop is made of glass, a 10-foot-long wood and fibre brush sits on the floor of the gallery with the affect of a slug or a crocodile, a table’s fleshy palette makes it repellant rather than inviting. This push and pull between known and new, comfort and disturbance, is central to Diyar’s work and how she talks about it.

Sociologist Avery Gordon writes in the introduction to Ghostly Matters that “haunting is one way in which abusive systems of power make themselves known and their impacts felt in everyday life,” saying later in the same paragraph that haunting’s distinctive characteristic is that it is “an animated state in which a repressed or unresolved social violence is making itself known, sometimes very directly, sometimes more obliquely.”1 Gordon’s haunting describes “those singular yet repetitive instances when home becomes unfamiliar, when your bearings on the world lose direction, when the over-and-done-with comes alive, when what’s been in your blind spot comes into view.” If you know Diyar’s work, or if you spend some time looking at documentation of it, I’m sure it will be apparent why I introduce this text in relation to it. Diyar is explicit about her interest in how the “strange” appears in the “familiar”, and in the bivalent or ambivalent impulse inside words like “home”, “house”, “guest”. The ambivalence there is not only at an intimate scale (our own houses, our own guests), it’s also necessarily at the scale of the historical. One of the things I admire about Diyar’s work is its refusal to confine itself to one of these spheres, or rather, to think one can. She resists the myopia of work that interests itself in what is political of house-and-home’s-objects (the rug, the table, the broom, the bed) only so far as it assumes their political charge is self-evident: that every private archive for instance needs only to be made public for its significance to the historical collective to become obvious, that only a change in context is required to make the personal’s particular political meaning interesting and widely available. By attending to and intensifying material strangeness in her objects and assemblages, what is already unsettled or unsettling in the familiar rises to the surface. A yeasty approach to the latent unease in ordinary scenes.

Sweep (2022), Cherry wood, natural fibers, 5” W x 8” H x 120” L, Photo Credits: Alberto Porro

In the spaces of state-sanctioned entry, dwelling, exit – I can’t say its spaces of hospitality – there tends not to be room for the ghostly. Inside the world of objects issuing out of Diyar’s imagination it seems instead that there is a ghost in everything. Who sweeps the broom in Sweep? Who makes the Silk Bed, and then sleeps in it, trying to avoid the hole at its centre? Who collects the Dustpan dust? Who signs the Guestbook? The absent figure each of these refers to might be our own labouring, devouring, ailing, leaking, diminishing body. It might be somebody else’s body in those same postures. It might be the body made absent by violent state intervention, or by the familiar “minor” violence of the interpersonally repressive.

Diyar says, “My hope is … [that] my work might translate into new bodily orientations and sensibilities.” Towards that end, we’re not left alone with an object “as is” to reify to ourselves what it already means to us: rug = comfort, broom = order, table = gathering, bed = rest, clock = time moving forward, or, alternately, rug = loss, broom = feminized labour, bed = unrest, table = argument, clock = time running out, etc. In other words, boring associations, no matter how deeply felt. We’re confronted instead by something recognizable but loosened from its moorings (“when your bearings on the world lose direction”). Sometimes functional but uncanny, sometimes useless in exactly the direction of the thing’s intended usefulness, a tool come back to life Frankensized as a sculpture.

Threads of ghosts, hosts, and more appear in our conversation, held on a July afternoon in Diyar’s bright, quiet studio on Chabanel Street. Characteristically, Diyar welcomed me with tea and lokum, and our conversation wound its way between the serious and lighthearted. We talked about being disappointed, about time, devotion, jokes, about available meaning, about persistent themes (language, infrastructure, ritual) and new preoccupations (containment, debt, water). The integrity of Diyar’s approach is clear in the conversation, and her work has the ring of truth in it because, after all, nothing is pure comfort, pure familiar, pure encounter – only the murky half-light of knowledge and love. If briefly, even if vitally, we find ourselves in an episode of safe mooring, soon enough again we will be shaken loose.

It's impossible to not think about bodies if I'm making work that will be seen by bodies...finding what is sincere comes through the body. And if the work is not sincere, it doesn't get to be art.

Thank you for having me at your studio. When I last saw you, you told me that you had just moved studios and that things might still be in boxes when we met up, so I thought we could start our conversation with a question about the studio and how it functions as a vector in your practice, or in general, what the studio means to you.

Even though I have a material practice – I make my own works, with help (usually people are helping me, rather than getting it fabricated entirely by others) – I approach the studio as a thinking space. I always have one foot out because fabrication often happens outside: I work with ceramics, so I need to go to a facility where they have a kiln; I work with glass, so I need to go to a facility with glass-work kilns, mould making shops that have safe ventilation, etc. But for me, the studio is where the whole thing comes together, physically and conceptually. When I make work, I bring it here and make tests and assemble them, to see them, to see how it feels. The parts that aren’t possible or safe to make in the studio I make outside, and that happens often. Part of the work almost always gets touched outside. Wood, for example, I can work easily with hand tools in the studio, but it has to be cut, planned, and prepared. I come here every day to think: what is it that I'm working on? But it's not just a decision. It's the unfolding of things. As you work with material, you decide, okay, do I go in this direction? Or maybe I’ll stop sanding now. In the same way, thinking is parallel. For that, the studio is very, very important. A place to come and be alone and think and write and read, even nap sometimes.

What is your background in terms of training?

I learned the techniques I use in my work through collaboration and training, but my background has always been in sculpture. I experienced many kinds of learning. I studied in Istanbul as well, where we had shops that were really focused on material. Discussions of concepts were never divorced from making. But when we were left alone in our own designated spaces, we were meant to use and learn from the teaching assistants and technicians how to use material. Maybe that's another reason why I never feel like separating them. But I don't think it's just that. There are many things I reject if it doesn't feel right. It just makes sense and feels right to me that material and concept are not separable from each other. For me, material decisions are conceptual decisions.

I'm thinking about you saying that there are so many things that you reject. When is that moment? Is it when you've made something and you decide it just doesn't fit? Or is it earlier in the process?

What I meant was the kind of education I got and the things I rejected from it. That's what I meant. But of course, when you're making things, there are things you reject as well.

[Diyar points to an unfinished sculpture in the corner.]

That one, I don't like it. It's ugly. We went cold on each other. I started it during the pandemic and it got locked up in the studio where I couldn't access it. And then when I went back there, I was like, who's this? I have nothing to do with it. The continuity was broken and I think I wasn't convinced by it to begin with. Sometimes it's going off but you can bring it to the sweet spot. But if you don't work hard on it, anything can be uninteresting. Especially the concepts I'm working with, it can just be an ordinary mundane thing. That's the challenge.

When you write about your work, or when you're talking about your work, you often say something along the lines of: I begin with the body. Could you tell me a bit more about what that implies viscerally in the process of the thinking and then the realization of the sculptures or performances or installations – how does it feel to begin with the body or what does that mean to you?

I think of a gesture that becomes a sculpture. And if that's not the case, I think of the body experiencing it. And why I am so anchored in sculpture is, it surpasses the eye. I mean, everything surpasses the eye, but it has more elements and space and freedom to work with that expansion. So, for example, how it starts with the body is that it has the residue of the body – for example, furniture, even unused furniture, even IKEA furniture, has the residue of the body because it suggests the body. Sometimes, it’s the residue of a human and imagining the human there that's not there. And sometimes, it is having the elements of signifiers of the body that become both familiar and strange. The handrailing sculpture, for instance, I thought of a gesture of holding – of supporting one's hand, not holding, but walking them into the room. I thought, how could I make a sculpture that does that instead of a human? How can a sculpture assist your hand, gently, in a gallant way, taking you around the room? It's impossible to not think about bodies if I'm making work that will be seen by bodies. That I think is the most straightforward answer. But of course it's not just that. I think through my body as well in the making of it. There is the side of making the work and putting it out there and letting it seep into the world. But finding what is sincere comes through the body. And if the work is not sincere, it doesn't get to be art, I don't think. So, there are many ways that the body comes into the work in that sense. Visually, gesturally, in the making, and also having the layered qualities of life.

I love the idea of work that seeps into the world. You just said it, and it comes up all the time as well, this idea of the interplay between the familiar and the strange, and it is very clear in your work. But there is this other relationship that you describe, or another kind of spectrum in the writing on your website about your work, the spectrum between “the gentle and the perilous.” I love that because it gets closer to something that I find really compelling about your work, which is exactly that kind of impulse that you're describing, where the person, the body, wants to make contact with it. You want to touch it, and when I think about the kind of touch, it is sometimes a gentle touch, but it's also sort of appropriately ambiguous, like – stroke, slide, crush even. So it's not exactly the kind of touch where you're in a park and you reach out to a monumental stone sculpture. I was thinking about Sianne Ngai’s “cute”, this impulse to caress that is simultaneously the impulse to dismantle or destroy. There are two works from your show last year at CIRCA Art Actuel, Taş yerinde ağırdır. (The stone is heavy in its place.), that I'd love to talk about more in connection with this. The first is one that you've mentioned already, which is the handrail. By the way, does that one have its own name as a sculpture?

No – sometimes I like calling them just what they are because they are also not that. I kind of like that people have that expectation, and it makes me feel like I made what I needed to make. For me, it is a challenge to take something so familiar and not let it be just a handrail but something more than that. That's actually not a very easy thing to do. I think that's the hardest thing that I take on with most of my work. The very recognizable is a really hard thing to work with, because it creates the image so easily. That recognizability can make the work look easy. But for what I want to do it's not an advantage if something is strongly recognizable, because it isn’t easy to allow it to become something else. For example: take a couple of bricks, put cardboard on top. Your mind renders a table so easily. So how do you turn it into a sculpture of a table, that allows you to pass that barrier of it being a table? Because you're so used to it being a table, you're so used to it being a handrail, you have expectations. It has a promised function.

I loved in the gallery space how the fingerprints and grease marks were accumulating on the handrail. That’s also very recognizable out in public, fingerprints on stainless steel. It's everywhere, in the metro, on the library steps, but the shift in context is really interesting.

The gallery asked if I would prefer it to be wiped every day, but I didn't want that, because instead of putting a text to say “you're invited to touch the sculpture”, the person who touched it before could give you that cue. It contributed to the publicness of that object. Our hands are our most public places, and that's the part of the body I wanted to start with.

I thought so much about hands in relation to that exhibition! It really prompted thinking about hands. In relation to the exhibition at some point you had mentioned handwriting, and handwriting in relation to your glossary. I'd love for you to tell me a bit more about handwriting in your practice, and also in relation to that show.

When I was planning the handrailing and its length, I thought about handwriting. Initially, it was supposed to be the first sculpture in the first section of the gallery, on a wall that is 20 or 30 feet long and then there were going to be many other sculptures. But I decided that short distance, even 20 or 30 feet, didn't feel long enough. And I remembered this graphologist who once told me that they usually ask people to write a full page. All they need is a couple of sentences, but in a full page, towards the end the control goes away, and people reveal themselves and their true handwriting. And I sometimes think of that kind of release, not just with this handrailing, but the stretching of time that is needed for experience. Even in meditation, it takes time to get into deeper concentration. Or when we fall asleep, we slowly doze off. So that slowness is in life, and I think it's necessary for thinking, for feeling and ultimately experiencing an artwork. I thought of this exhibition in a way that – it's devotional. There's something devotional about stroking, and walking around the perimeter of a place, coming into contact with something. What we already feel comes closer to us through a material encounter that has nothing directly to do with the feeling, and time is an essential part of this process. So, sometimes I think about touch in that sense. It brings you close to the things that are otherwise abstract, otherwise difficult to grasp.

I feel like that relates to this hope you describe that your sculptures will reorient the body. Thinking about it as a kind of devotional space, the body leans and literally changes direction in devotional scenes. To kneel, to turn in a certain direction, to face up or face down, or reach out. I love that.

I'm not thinking about religion but more gestures of comfort, honestly. But in every kind of gesture, for example, like that gesture of holding someone's hand for guiding them or welcoming them to a space. When someone is given a hand, even as old-fashioned as it is, I ask myself, why do we do that? Why does it feel better? How could I make it more gentle? In the handrail’s first form I was thinking about the psychological aspect of support. So that's why I wanted to take it out of its function of actual leaning and being the holder of your weight. Holding your weight, but instead holding your other weight. To make you think of that other kind of weight. That's why I was trying to use what we know. To use it as a hook. As an invitation to something else we know but don’t think of.

Can you describe the handrail sculpture, for readers who haven’t seen it?

The handrail is close to the wall. It's the first sculpture you see in the exhibition. And it has brush bristles embedded in it, directed towards the wall. You don't see the bristles at first – I didn't want them even to be imagined before. Only as you get close to it, you see the handrail and then the bristles. Almost no one that I have interacted with or have observed with it closes their fist around the handrail, because you don't grip tightly onto the handrail if you want to touch and be caressed by it. So there's a sense of release. A feeling of not leaning on it too strongly. Also, it's so long – it goes all the way around the gallery space, including going without interruption around the columns. Like taking a breath. A sigh. Exhaling. It goes all the way around the room, so it kind of invites you to walk towards the end of the room. It's not polished completely, the aluminum. So it takes fingerprints. People leave their residue on it. And that becomes a signifier of being able to touch it. Most people I’ve seen have touched it very gently. And I was hoping and was so happy that this happened – people continued walking. They continued touching it. They already know after a few feet how it will feel. But it seemed like they felt like this was a task, to stroke the whole handrail. Almost like blessing this whole room with their presence.

Taş yerinde ağırdır (The stone is havy in its place), 2023, site-responsive installation at CIRCA

Taş yerinde ağırdır (The stone is havy in its place), 2023, site-responsive installation at CIRCA

It's so nice to trace the periphery or perimeter like that of the room. Now I'm imagining entering other spaces and other rooms and doing that same thing. Touching the wall around the entire perimeter.

I was making this work when I went to Banff for a residency. I was working on some other pieces but in my free time I was just putting together these bristles. It was quite laborious. There were a lot of bristles to prepare. I shared it with some of my colleagues there. There was an artist, William Franco who is based in New Zealand. He said for Maori, when they go into a room before a ceremony, or it's the first time, if I'm not wrong – they go around the wall and touch the whole wall in the perimeter. I was surprised that some people use this to understand and feel a space, to bless a space with their presence or connect to a space even if it's just four walls. That was surprising to hear – not just surprising but I was delighted to hear that people are already doing this.

Still thinking about Taş yerinde ağırdır. (The stone is heavy in its place.), the other works that I haven’t heard you talk about as much that I’d love to hear more about, are the compressed graphite sheets at the back. I’m wondering about the process of making those, fabricating them but also the text that is on them. What is your process of arriving at the words that will be made public in the exhibition?

This work is one of the only times I’ve used text. With the Guestbook I shared text that informed the exhibition, in a visual way. But for this exhibition and its title, I was thinking of a proverb that in a really concise way explains the feeling of displacement, even with how complex it is, how wide it is: a stone that’s not in its spot, in its place. So I wanted to use this text, and I thought of it on the graphite because the material is opaque; it blocks not just light but energy and fire. It’s used in nuclear stations to contain heat, to insulate, and it’s used to retain energy in batteries. If you break open a battery you’ll find something similar. This very opaque material that is used to contain, and isolate, to create a better barrier. We don’t see it because it's always placed between, as insulation. We do see it in crayons even if they’re not made of real graphite. It’s something that we know. But I wanted to have the text on it because of its opacity. I wanted a text that’s not understandable. Sometimes people try to play detective in exhibitions. What’s the artist trying to do? What are they trying to tell me? And I wanted to have another layer of opacity that is not physical. Some things are not translatable. For me, this sentence, this proverb, describes so much about displacement. It makes the human a rock. Proverbs are not easy to translate, and I didn’t want to translate it. But it wasn’t a state secret! You could find it out if you wanted to. Not being legible. Not being a readily available meaning. That’s what I wanted to emphasize – to put the viewer in a position of not understanding. Because that’s also part of it, when it comes to support, when it comes to otherness.

There’s a necessary unknowable.

That comes through experience. When you see these [graphite] curtains, the text isn’t visible from far. Because it’s not a different colour, it’s just an embossing, and it catches light – as you move you’re thinking, oh is it a reflection? Am I not getting it? And you come close, position yourself, and you think of your position too. I was thinking a lot about positionality. Physically, the viewer will have to stand in a certain position depending on the light, the time of day, to be able to read, only to find out that they cannot. The rock on the engraving is already that text, visualized. It looks like an imprint, it feels the weight of it.

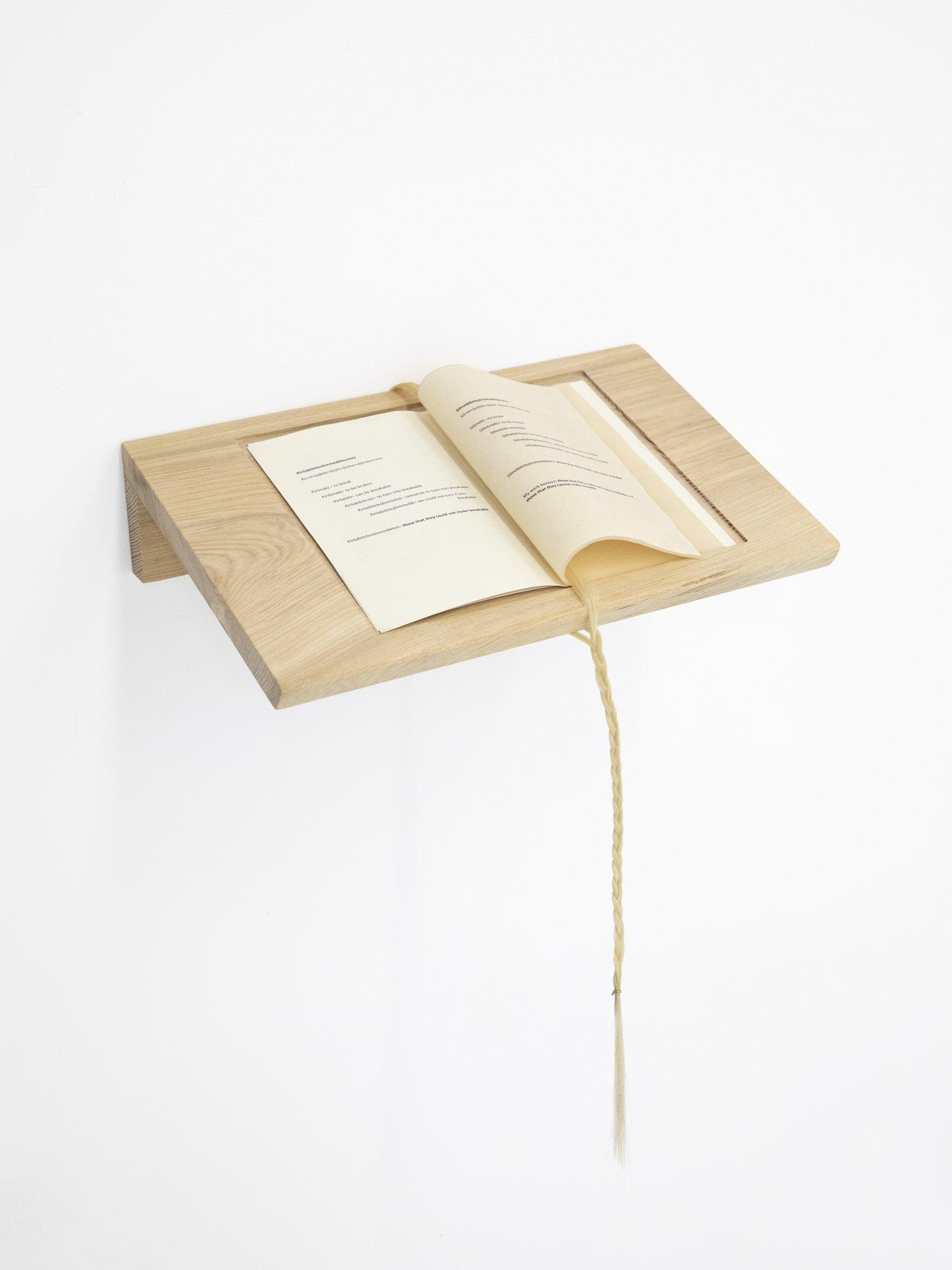

Guestbook (2021), Text, silicone, wood, natural fibers, 12” W x 17” L x 4” H. Photo Credits: Alberto Porro

There’s this thing that I’ve been trying to describe, that feels important in your work – I feel like it sort of functions the way that a joke functions. But, in a serious way as well. There’s the invitation, and then there’s a surprise of some kind, but inside of that surprise there is an unknown. The thing in a joke that you can never name. Why it’s funny, what exactly makes the joke work. Maybe that’s also this gestural thing, of the pull in. You pull in and then you reveal. But there’s a limit to what you reveal. Or it’s that you’re revealing to the person who is encountering the work a certain limit in the world or in them.

I don’t know if this hiding comes from the idea of a joke. I don’t think it does. But humour, jokes, necessitate thinking of something in a different way. That might be the commonality, but not the funniness. Sometimes you say, “there’s something funny about this,” and we definitely don’t mean something that is haha. We think that some bad thing might happen. Funny in the sense of not-ordinary. But I think the hiding is not to make it mysterious, I think it happens really naturally. Even when I look at my very old work there is always this effort of hiding, revealing. This habit of mystery.

In Turkish there’s a saying: for those who won’t hear, you might play all the drums you want; for those who’d like to hear, a mosquito is enough – anlayana sivrisinek saz, anlamayana davul zurna az. I sometimes see this kind of impulse in some of my students, in some art – not just art, even, just people voicing themselves – groups of people who have been misunderstood, ignored, unseen, they start to make… Kurdish people for example. I love Kurdish cinema. Sometimes I’m like, this movie is going to be great! And it starts great, but it overly explains. And I feel like it’s not because the director lacks creative vision. It cannot be a coincidence that my people over-explain themselves, because we’ve been waiting to be understood for a long time. And I think this happens naturally – I’m trying to understand this and I don’t know if I understand completely yet. But I completely refuse to do that. And I have always refused that. Growing up I was told to hide, maybe that’s why I refuse that. Because I’ve experienced – despite your maximum effort, well, you cannot hide. So if you’re able to see my Kurdishness despite my effort to speak your language in the most impeccable way, I think you can see when it’s necessary to see. So it’s kind of like selective seeing. And I’m aware of this, and this will not be an exaggeration to say, I’ve been aware of this since childhood. So for me, that’s why I don’t get convinced of over-explanation. That’s also why sometimes interviews are hard for me [laughs].

When something is not visible it doesn’t mean it’s not there. And through that effort of making it invisible, you make it even more curious. But that aspect of my work is not speaking about my Kurdishness. I don’t make work about this. I make the work I make. I just believe that this is maybe one way this experience visualizes in my work. I think a lot of things are for all humans, all of us. That’s why I’m so interested in feelings. Disappointment – disappointment as we can say it’s a feeling, and it was experienced and felt since we ever existed a million years ago. It was a disappointment – I don’t know – the first clay pot you made, it broke. It’s a disappointment. So I think it’s timeless. Not only are feelings for everyone, but they also break history. This is another reason why I’m more interested in feelings. And for me explaining feels like it interrupts this. And visibility is a form of explaining. Meaning that is readily available is a form of that as well. In this exhibition, it’s a text that leaves a little bit of the thing that’s not available to you, unless you really want it. It’s translated in the exhibition title, if you wanted to know, but it’s also not important. I like to put people in a position where they need to get there. Understand that not everything is available. There are layers. Proximity is not just for the eye, but also for meaning. I think a lot about proximity when I’m thinking about my installations.

The fantasy that what is required in order to be known is just to reveal more of yourself, or explain more of yourself, that’s actually the fantasy of whatever entity is dominating another, because that allows power to just keep functioning the way that it is already functioning. To say, you haven’t adequately explained yourself. Or you haven’t adequately proven your right to exist.

There isn’t much to explain anyway. It is an invitation to an experience, this exhibition. The hope of allowing you time, space, and tenderness. I never imagine that people come into my exhibition and understand me. It’s not about me. I make it, but it’s not self-expressive. I find it also quite… I don’t know if I ever make this kind of work, maybe I do sometimes, but I’m not trying to express myself. But don’t write this, it’s so obvious – nobody wants to do this. Or, people say they don’t want to do this, but they do. [Laughter]. It’s like, who cares. First of all, I don’t want anyone to come to my exhibition and understand me. Like they are my parents. I don’t even expect my parents to understand me at this age! So what, society understands me! If you ever ask me, I want society to respect me. That’s more of a desire that I have. But that’s not about my work. Going back to the work, for me it’s more a way to connect with the world and the humans in this world, through the sculptures. In the commonalities, and the things that I cannot control, too.

I was remembering last year when you gave me these graphite sheets you had wrapped them really carefully and you delivered them to my door and unwrapped them and we were just standing on the balcony, flipping them back and forth to read them – on one side it says: On it we gathered in pockets of time, on the other side, Pockets of land was what we were left with. So you see each of those sentences either forwards or backwards and it requires, or invites, that gesture of flipping. But I’m wondering what you’ve been thinking this year about land and time and their relationship. Is it something that you’re still thinking about?

When I made that piece I was thinking about land, obviously. And it was because I’d read and seen these big prints you had made that were about mining. When I think of mining, even if the land is not taken, even if these mining companies come out with “hey we’re just here for the gold, after we’re done we’re gone, you can use your land,” but what’s left of the land is just pockets of what it used to be. And when you asked us to bring something that would fit in a pocket, I’d already thought a lot about pockets when I was making that table – there were these bumps underneath and there were supposed to even be pockets in this work, I didn’t do it finally but I thought of the pocket being this small place and how it’s used metaphorically for things that are not related to garments. Time for example, pockets of time, we understand small amounts of time here and there, we right away understand that. A pocket is never on its own – it is attached to something else and is part of something else. And I thought of how I could talk about land that is being exhausted, and make it visible. It’s easy to visualize a pocket, and how small it can be, but also how it can become precious.

People who are custodians of these lands, wherever they are, in Canada, in Palestine, colonized lands, exploited lands, not only are they left with small land but small time. And I wanted to put resource and time together. You don’t have enough time, enough energy to gather, even. So you don’t form a strong union against the colonizers, or gain power. I mean if you’re robbed of your wealth, not just in the form of mining but also your time, what you’re allowed to do with it and everything. I thought of people that would be able to enjoy each other’s company, connect to their people or community, only in their break times that are given by someone else who is stronger or more powerful than them. Who has pockets of time? I don’t think wealthy people. Wealthy people don’t have pockets of time. No one tells them, “your smoke break is over”, “you’re going to the washroom too often”. That’s why I thought of that. One writer I admire, Toni Morrison, I like her because she finds adjectives that don’t relate to humans and puts them together with humans. And she takes human adjectives and puts them with objects. She’s doing with words what I’m trying to do. When she was talking about the everyday lives of slaves she used the words pocket of time in a sentence, it wasn’t a significant sentence in the story but for some reason the visualization of pockets and time really stayed with me. And when I thought about land it came together.

.jpg)

Sitting Through (2019), Silicone, ceramic, wood, salt, 30” W x 30” L x 33” H (76.2 W x 76.2 L x 83.82 H cm). Photo Credit: Alberto Porro

Sitting Through (2019), Silicone, ceramic, wood, salt, 30” W x 30” L x 33” H (76.2 W x 76.2 L x 83.82 H cm). Photo Credit: Alberto Porro

The exhaustion is of resource in every sense.

I try to show, not tell, and even if I use text that’s what I want to do, so I didn’t talk about mining, didn’t use the word colonization or anything, but I think the fact that you’re left with small chunks of land, you’re left with small chunks of time… I wanted to use graphite because it is a material that crumbles like earth – it’s basically made from charcoal, it comes from a material that relates to mining, it’s a mineral.

What materials are you working with currently or coming up?

I’m thinking I want to use some stones. And water. I’m thinking a lot about water. But I’m not sure if it’s going to be in the exhibition. Sometimes you think of water and you notice that you’re actually interested in the reflection, or fluidity, or something else. I’m not there yet. But I’m thinking a lot about relics. I think that’s the bridge to the recent exhibition at CIRCA. That touching, and coming close to the material, to come close to something abstract, such as your feelings.

Like disappointment.

Yeah, or any feeling! You know, like support. That is also an abstract thing. You feel supported because someone tells you some words. As much as it can be physical. So I’m thinking of using water. I’m very interested in little pools that you don’t go in but just look at. Decorative ones. They are very integral to mosques. And again, I’m not making work about this, about Islam or a religion, I just like to observe the visual language, which is really ingrained. Also the holy water at the entrance of churches – it keeps repeating, this water image. I’m thinking right now a lot about waiting. And anticipation. And how water symbolizes, by reflecting the sky, heaven on earth. It is almost like a portal to heaven. It’s hope, we drop coins into it. Maybe I’m thinking more about hope, I don’t know. Maybe water is just an apparatus for me to think about those things. I’m not sure if water will be in the exhibition, but I’m thinking a lot about how hope and fear are just like that back and forth. Wrong and right side of the fabric. Inseparable. You’re hoping something happens – you fear that it might not. You fear something is going to happen – it’s something that you don’t desire. When you fear something, you hope. I’m thinking a lot about this because that has been my feeling since I took down my exhibition. That was the most dominant feeling.

We were, I think, people who were able to see what’s already available and visible… and I hope the world won’t get worse. I’m thinking about waiting in terms of a historical debt. That is unpayable, but it’s a debt nonetheless. I’m thinking of tally sticks – how before money, or when money was not available, if there was shortage of metals, they put lines on sticks to mark the exchange. Even in the absence of the possibility of payment. You could offer both. And also containment. About water, and the containment of debt, and waiting for the future. I mean it’s very abstract right now but I’m gonna get there, it’s really at the beginning. Those are just the seeds, they haven’t germinated into being works yet.

I’m excited to see the work when it materializes. I have two closing questions which in a way I think maybe we already covered, but one of them we could skip which is – as you know I was thinking a lot about ghosts as I prepared for the interview.

Oh I like this question!

Oh yeah? [Laughs] What do you think about ghosts?

I want to be a ghost when I die. I don’t care – cremate, bury, whatever, I’m going be a ghost. I don’t know. Then I can make jokes.

You would be a really funny ghost.

I hope so. Something can be funny in that context, but when you don’t know what it is, it can be very scary. But ghosts – I really like this idea, Morrison uses this metaphor in her books. Especially in Beloved. And that debt that I’m talking about, that will haunt you, and being haunted. Things you cannot escape the burden of. The burden of trauma, of the past following you in that sense. I think ghost is a good metaphor. Also on another note, I don’t… it’s very difficult to describe this. You don’t even have to believe in God really, but we, Kurdish-Alevis, have a strong sense of superstition, and Morrison – another reason I love her – says: as I grow older I believe in superstitions and all these things more, I think our ancestors knew something. And I do kind of think we sense things. Just because we try to describe it in our own terms it seems irrational, but it’s not… yeah, I believe in ghosts.

Other than Morrison, are there writers you’re reading right now or that have been “haunting” you?

When I’m at this stage of a project that is just taking form, that is becoming, I like to read poetry and also I like to read Etel Adnan. It’s short, I can start from anywhere, and I open often, just when I get bored, this one, In the Heart of Another Country. I have an affinity towards it because it is almost like a glossary. It starts with words and it repeats them multiple times, she describes – peoples, education, business, peoples again here. When it comes to haunting I just finished Pedro Paramo by Juan Rulfo, and I found a great deal of inspiration from how his writing pulls you in and out of reality. While reading I kept asking is this character (who is doing the most mundane things), alive or a ghost? A new book that I was reading is Baby Book by Amy Ching-Yan Lam.

I love that book.

Yes, it’s really good. Another fragment book that I love is The Secret Heart of the Clock by Elias Canetti. I’m not actually reading Etel Adnan cover to cover, it’s just always there, but I’m reading Baby Book and the poems of Paul Celan.

Do you have any lingering thoughts, last thoughts that you haven’t said that are buzzing around?

I don’t think so – I didn’t take too many notes. No – when we talked about the studio I forgot to say one thing I think. You know how I said I’m not explaining myself. I would rather you don’t write this because it’s obvious. I like to start the work with a question. I ask myself a question, and usually I find myself after this laboursome whole year of making the work I still have the question. That’s something I think that is significant to how I make work. Because I think I almost find it successful that I still stay with this question and if the question is still open in the exhibition. I’m not inventing this question as I make the exhibition, rather I had this question, I make the work, I still have this question. Am I a failed artist who can’t answer her own questions? [laughs] Maybe, I don’t know. Because what do I know? And what do you know? Nobody knows nothing. Don’t say that, don’t put that.

That’s the perfect last line.