Hundreds of phones, tablets, and video projections flash in dissonance. Water cascades over touchscreens, tapping, swiping, and scrolling through websites and apps. This endless flow of information animates the hypnotic whiplash of Yehwan Song’s multimedia installations. A Korean-born, New York-based web artist with a background in UX/UI design, Song stages dystopian fantasies of the digital world that subvert the notion of “user-friendly.” Saturating screens with fragmented images of her own body, Song leans into glitch aesthetics (or glitches), seeking out the loopholes and flaws that most interfaces work to conceal. Through immersive installation and interactive performances, Song hacks the design logic of machines, tinkering with her websites, videos, and sculptures to expose the hidden infrastructures of digital systems.

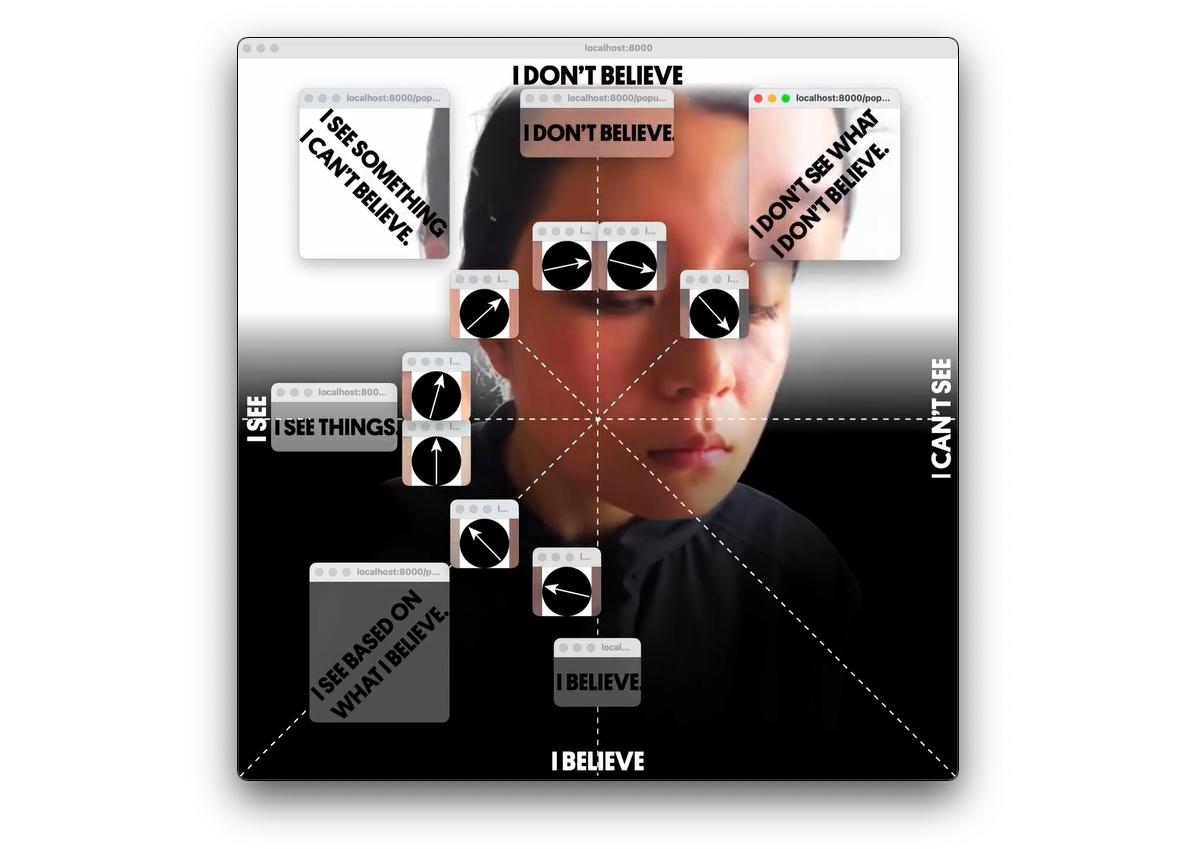

While Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto (1985) imagines a fluid entanglement of human and machine, and Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism (2020) considers error and disruption as acts of resistance, Song mobilizes these ideas in the everyday mechanics of the internet. As Dawn Chan observes in her writing on Asian Futurism, “When real Asian Americans—by which I mean people and not stereotypes—appear in media, we do so in the future, but not the present; in alternate realities, but not this one.” Song’s work, by contrast, insists on the immediacy and instantaneous feedback of the present internet. In opposition to techno-Orientalist tropes that situate the Asian female body as a speculative projection into distant futures, Song positions her own body as tethered to the present, caught in the banalities and absurdities of network culture. Her work interrupts and confronts the sensory overload caused by data infiltration and bombardment. In a digital world that promises freedom, Song contemplates how design interfaces shape perception and agency.

Glitching connects to the imperfection of the internet, which feels humane to me. When I encounter a glitch in technology, it’s like finding a friend, a human presence within all this digital sophistication.

You have previously said that your work adopts an “anti-user-friendly aesthetic.” Could you tell me more about what this means and share some examples?

I’ve always been fascinated by user behaviour, even more than the online space itself. There’s the internet, the websites as a platform, and the users interacting through screens and devices—the UX and UI. What interests me most is how people’s behaviour and thinking shift because of these interfaces.

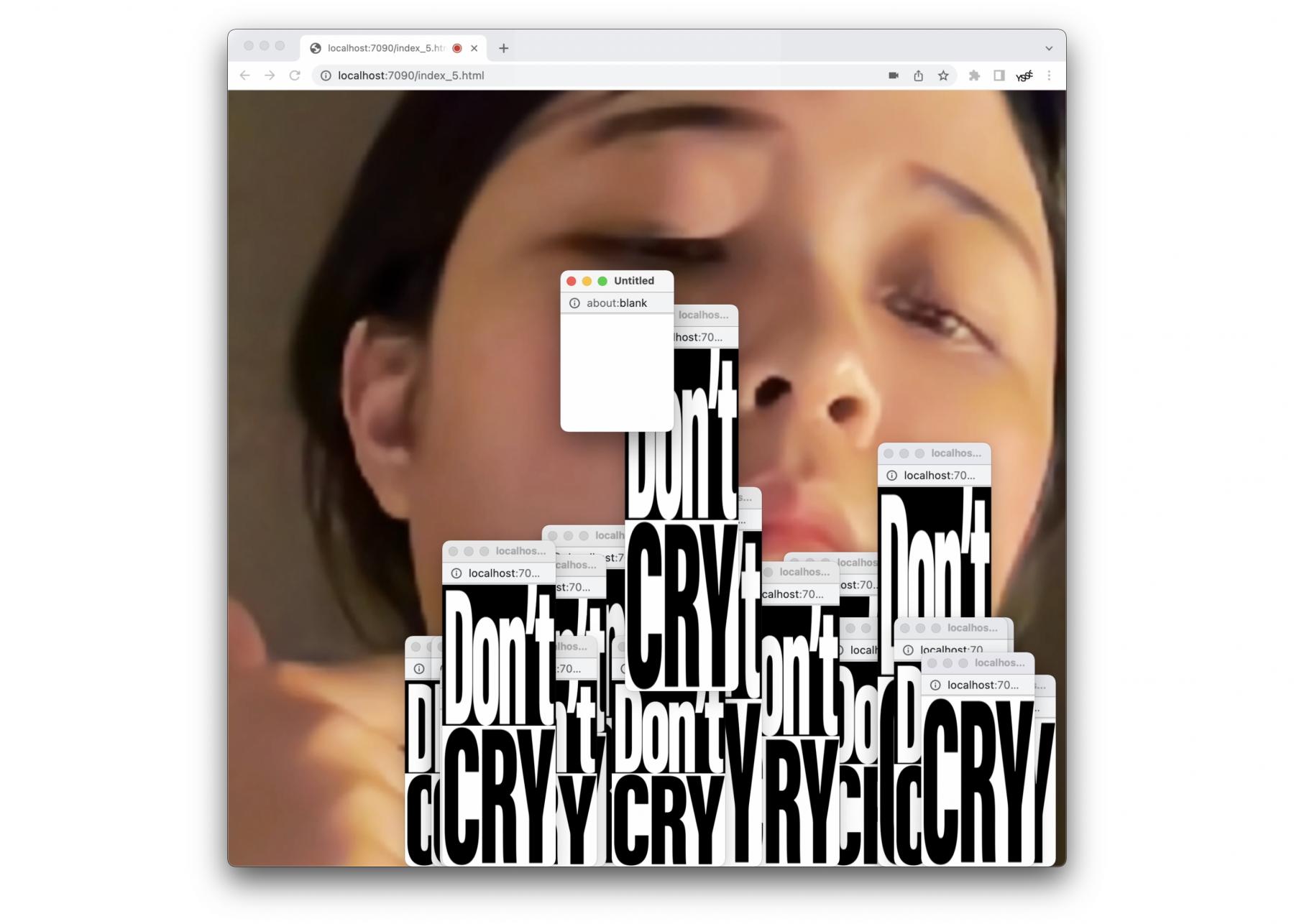

My “anti-user-friendly” projects ask users to think about the internet outside the “user-friendly” boundary. In today’s world, we’re conditioned to follow narrow design strategies that train users to repeat the same gestures: scrolling and swiping, consuming content we don’t necessarily seek. Content refreshes automatically, and users rely on habitual, repeating actions without really thinking about what we’re seeing. I found this deeply problematic when I worked as a UX/UI designer before becoming an artist. My experience made me want to break these patterns and ask: what are we missing in this fast-developing technological environment? How can we become more honest and human in this era?

Being an artist allows me to reflect on my own habits and constraints. One of my ongoing projects involves a fountain that sprays water onto touchscreens. Since water conducts electricity, the devices register the droplets as human touch, revealing how naïve technology is—equating conductivity with humanity. I find it funny because we’re usually told to protect devices from water, but here, the devices are intentionally immersed. I’ve ruined a lot of devices while working on this project, but it’s part of the point.

Touchscreens are also fragile in other ways. Certain hand positions prevent proper registration, while dirt or smudges can block detection. These small fractures in user experience fascinate me. They’re uncomfortable but ever-present, and people accept them instead of questioning their design. This passive acceptance exposes how much control technology exerts over us.

Speaking of water, in your recent solo exhibition at Pioneer Works, Are We Still (Surfing)? (2025), you’ve used metaphors like “surf,” “port,” and “stream” to explore internet mythologies. What draws you to these metaphors, and how do they inform your approach?

I find these metaphors fascinating because the internet is hard to define—it has no fixed shape or tangible form. Water’s unpredictability mirrors technology’s uncontrollable nature. Water is powerful but also dangerous, and I use it to explore both the utopian and hazardous aspects of the internet.

Tracing the origins of these metaphors, early researchers and writers likened the internet to water in order to suggest its possibilities as a fluid, massive, and flexible space. This language continues today in terms like “streaming,” “cloud storage,” or “data flowing.” It reflects a sense of hope embedded in early internet culture that, like interconnected water bodies, we could connect people globally in ways previously impossible. This optimism is part of why water resonates so strongly with me.

Your installation The Barnacles (2025), presented at Frieze New York also uses water imagery to explore the internet's ecosystem. Could you tell us more about this piece?

Barnacles are marine organisms that live in clusters and cling to surfaces and large structures, passively receiving water and waves instead of “free-surfing” the ocean. I am interested in them as a metaphor for internet users. People often think they’re browsing freely online, but in reality, algorithms embedded within social media platforms keep them contained in small, self-reinforcing bubbles. The barnacles symbolize this kind of passive engagement.

On these platforms, users are automatically fed curated information, forced to “ingest” content that comes to them rather than exploring on their own. The UX/UI may look polished and seamless on the surface, but underneath, the systems are messy and unpredictable. That imperfection is what I’d like to examine—the invisible forces that users are subconsciously affected by.

Some of your works incorporate glitching as a technique. What does glitch mean to you aesthetically and conceptually?

Glitching connects to the imperfection of the internet, which feels humane to me. When I encounter a glitch in technology, it’s like finding a friend, a human presence within all this digital sophistication. I love discovering glitches, revealing them, and incorporating them into my work. Instead of fixing glitches, I play with them, let them emerge, and sometimes even create new ones, extending them into an endless cycle of glitching. Glitches don’t just exist in my work; they reflect the way I think, the way I interact with technology, and the way I’m always learning from it.

Your work engages with the representation of Asian women in digital media. How do you use your own body to challenge dominant male and Western narratives within the history and visual culture of the internet?

I use my face and body to present a real Asian presence, not a stylized or animated version, but a human face actively interacting with digital environments. It’s about asserting visibility and presence as an Asian person within online spaces.

I’ve always felt dissatisfied with how women’s images are treated on the internet. AI-generated images often reflect distorted, male-centred perspectives. While working in software development, I witnessed firsthand how male-dominated the field is: women’s contributions in tech history are frequently erased or overlooked, while men are celebrated for the same achievements. Women are often positioned as users, yet the history of computing and the internet shows that women played significant roles in shaping and building these systems. Through my work, I aim to highlight their labour and reclaim the Asian female body as a contributor to the structure of the internet, rather than merely an object within it.

Your practice first began with net performances and later expanded into video installation and immersive environments. How did this shift in medium influence the way you think about technology, space, and audience interaction?

In my early work, I focused on performances where I used my body to interact with devices and websites in exaggerated or repetitive ways, presenting myself as a user. Over time, this expanded into immersive environments combining video installation and performance, allowing me to explore user behaviour in a more cinematic and interactive way.

The body is central to my work. At Pioneer Works, for example, I use my hands, face, and presence to reveal the repetitive behaviours users unconsciously perform, exposing how digital environments train, restrict, and sometimes possess us. My body becomes a tool to make these subtle constraints visible. Hybridity emerges not just in the blending of form and media, but in how technology and the human condition continually reshape one another.

During my performance at Late at Tate Britain: Digital Intimacies (2025), I interacted with a large audience through the camera—rotating my face, scrolling text—but was physically alone in my room, staring at a tiny Zoom window. I met people virtually yet felt completely isolated. In-person installations, on the other hand, allow me to engage directly with the materiality of devices, projections, and space, even when glitches or unexpected problems occur. Working across media allows me to explore these dynamics in distinct ways. The tension between connection and solitude is something I keep exploring in my work.

Net art performances have deep roots in early internet culture. How do you situate your practice within this history, and which references have inspired you?

Many of the pioneering net artists from the 1990s continue to inspire me. Technologies have changed a lot since then, but their focus on revealing the human dimension of digital culture resonates deeply with me. For example, Olia Lialina’s frame-by-frame animations, which parasitized multiple websites, created dynamic and interactive works that embraced unpredictability. I also look to artists like Aram Bartholl and Constant Dullaart, whose practices examine the structures and aesthetics of digital culture, to shape my own thinking about my work.

For your installations, you incorporated a range of materials including cardboard, phones, and iPads. Could you walk me through your planning and construction process?

My construction process is never linear. I think of my installations as a kind of theatre, where the structure supports the story I want to tell. I usually start with a rough idea of the structure, then consider the videos I want to include. Often the videos prompt adjustments, so I rebuild or modify the structure as I go. For instance, the circular-shaped installation at Pioneer Works was inspired by a whirlpool, and the structure evolves organically from that initial idea. The screens and devices add another layer, creating a dialogue between the physical and digital components of the installation.

I work with fragile materials like cardboard, which alone aren’t strong enough to support a large installation. To make it stable, I weave multiple units together, layering grids on top of one another until the overall structure becomes rigid. The process is similar to coding, mirroring the layers and intersections within network infrastructure.

Where do you source the screens and phones? Does sustainability or recycling factor into your practice?

Many of the devices I use are second-hand. I’m particularly interested in leftover technologies, things discarded even when they’re still functional. The tech industry encourages constant upgrading, and I started collecting cast-off devices to question this cycle. For instance, when the iPhone 15 came out, many people discarded their iPhone 14. Sometimes they are resold, but often they’re simply abandoned. The massive digital waste highlights global inequities, where discarded devices from the US often end up in developing countries.

It seems to me that it’s not only about functionality, but also about keeping up with trends—the constant pressure to always own the latest model.

Exactly. This pressure is both frustrating and fascinating. Consumer anxiety around upgrading is very real. Stores make trade-ins easy, but few people think about what actually happens to their old devices. Some components are resold, but many are too small or considered worthless to recycle. Burning them releases toxic chemicals, but proper disposal in developing countries is often impossible. As a result, e-waste becomes stranded, leaving behind a toxic legacy of tech production. In my work, I try to show alternative ways of engaging with devices, demonstrating that the “latest model” isn’t always necessary.

Your installations often respond to the specific spaces they are in. How do you think site specificity shapes the audience’s experience?

The units I use are always the same, but I assemble them differently depending on the space. Sometimes the structures become larger or more complex to suit the environment. Again, I think of it like coding: the components remain the same, but their arrangement shifts depending on the “server,” which is the location.

I am curious how audiences have responded to your work.

People often misunderstand how the work is constructed. They assume there’s an LED screen embedded in cardboard, when in fact the images are projected. There’s an expectation that new media art will always use the latest, sleekest screens, so encountering a projection on paper unsettles those assumptions. It “glitches” what people think they know about technology.

Speaking of our relationship with technology, do you think digital media brings people closer together or further apart?

I think online connections can create a kind of human relationship, but it’s never the same as real, in-person interaction. During COVID, we all tried hard to maintain connections online but it can never fully replace physical presence. Maybe future generations will feel more comfortable meeting people digitally, but for those of us who experienced in-person relationships first, online interactions feel very different.

It’s fascinating to see how dating apps, for instance, have exploded. Sometimes you don’t even see someone’s real face—they are hidden behind virtual masks, avatars, and curated personas, which can make genuine connection harder. At the same time, anonymity allows people to reveal aspects of themselves they wouldn’t show offline. In real life, your face and presence come with expectations and responsibilities, but online, you can perform in totally different ways. This dynamic between revelation and concealment is what I find compelling.

What are you working on right now and planning next?

I am researching how the role of the user has changed over time online. In the early internet, the user was always the end client. Software, UX, and UI were built to make it easy for people to use devices. But now, in this AI era, the user has shifted from client to data source.

To be visible on the internet, the user no longer has to actively conduct labour in the old sense, like posting every day. Platforms like Instagram are intentionally structured so that users generate content simply by interacting with the platform, and that information, such as time spent on each story and user preferences, becomes the company’s data. It’s fascinating and a little scary how much the AI era has changed the dynamic: the user now does labour for the system instead of the system serving the user. Sometimes that data is sold to governments or other entities, and privacy becomes a huge concern.

Even small things, like receiving random emails or figuring out where your information has been shared, reveal how data extraction happens daily. Some people have found clever ways of testing it, for instance, slightly altering their name or email to track how their info gets used. Even without these tests, I notice in my own life how my data is used. For example, I might be looking up a show casually, and suddenly my phone is suggesting it all the time. It’s almost as if the internet is constantly watching and steering our behaviour. This recalls my Barnacle work, where users remain stationary as forces beyond their control determine the information they receive. We’re always online, and our actions are harvested as labour for algorithms: posting, subscribing, following, just to maintain visibility. It’s almost as if users become servants of the internet.