Natasha Stagg. Photo by Jody Rogac.

“When the sky was dark, I went down to my room to heat up a clothes hanger and press it against the back of my thigh until it went cold.” I read most of Natasha Stagg’s coming-of-age novel Grand Rapids (September 30, 2025) in the Flemish countryside on the 29th of June, with the sun burning my SPF-free skin, Marlboro Golds clouding my lungs, occasionally sipping “vodka, basil, cucumber & ice” gimlets. Stained by sweat or the gimlet’s thaw, some pages wound up saggy and soft.

It occurred to me that, like the protagonist’s, my teenage years were long gone—my memories possibly thwarted, or tainted by my own interpretations—their patina forever scraped, they’ve become a cozy place of no return.

“I watched skateboarders do tricks in front on railings. Their legs had no knees in their big Gumby pants. There was no outline of a bone to break. The sound of the wheels going over sidewalk seams was a ball scuttling over a roulette wheel but endless.” It’s 2001 and Tess, Stagg’s protagonist, describes the scenery in front of a hospital. She’s fifteen and works at Berrylawn Assisted Living, the fictional nursing home in Grand Rapids, Michigan. She has moved in with her aunt, uncle, and their kids, after her mom Sheila dies of cancer. She hates it here. Tess is three things: intoxicated, angsty, and sexually awake.

I recall when Stagg’s deadpan voice clawed its way under my skin for the very first time. It was a short story about a garbage man she dated in New York, published in her 2019 collection Sleeveless. Tragic, glamorizing, yet brittle, the author confronts highs and lows, and the fatal ineptness of social hangouts some of us may find familiar. Or at least, I did.

On a sweltering day in July, I noticed that there were just a few pages left for me to finish Grand Rapids, and felt a familiar tug in my stomach that confirmed what I’ve already felt many times before: I didn’t want the novel to end.

Natasha Stagg is a New York-based author and editor notorious for Artless: Stories 2019–2023 (Semiotext(e), 2023), Sleeveless: Fashion, Image, Media, New York 2011–2019 (Semiotext(e), 2019) and Surveys: A Novel (Semiotext(e), 2016). Grand Rapids is her second novel, which will be published on September 30th by Semiotext(e). She grew up in Tucson, Arizona, and attended the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. She is the former editor of V Magazine and VMan, and her work has been featured in books by Amalia Ulman and Vanessa Place. Her essays, stories, and interviews have appeared in The Paris Review, Granta, Frieze, Spike, Highsnobiety, and AnOther magazine, among others.

Stagg, who is equally known for leaving Instagram as for her hot takes on fashion, online fame, and cultural and social media trends, told me during our August afternoon Zoom that her cultural interests have shifted, and so has her writing. Grand Rapids is its beacon. Stagg and I spoke about returning to writing a novel, about quieting things down and being aloof, working in a nursing home, movies like Gummo and Kids, eighties music, and being out of the loop. “Do I ever have hot gossip?” She asked.

Chatting with the author via screen, Natasha pondered the idea of slightly misrepresenting oneself on a first date as a guiding principle for the book. She shared her current perspective on the Substack-fueled era and commented on the potential bursting of the AI bubble and its implications for writers. Stagg’s iridescent yet austere voice in Grand Rapids does not orbit around the new cool; it no longer needs to. Outgrowing zeitgeisty commentary and returning to fiction, the author holds the grip on what’s at stake for her right now. It’s about telling a story, Tess’s coming-of-age story.

You can order Grand Rapids and subscribe to the author’s Substack, Selling Out, to support her writing.

I was thinking about how the memories of adolescence turn into these fables that you tell in the future. They don’t have to be real because eventually they’re not. What’s more important in the present is the mode of telling.

Let me ask you my first question. Grand Rapids (2025), a coming-of-age novel which will be officially out on September 30th, is the second novel under your belt after your debut Surveys (2016), about a twenty-three-year-old who becomes influencer-famous. But you’re equally notorious for writing Sleeveless, and most recently Artless, each composed of stories, fragmentary essays and press releases. What made you return to literary fiction format? What did you have to say with Grand Rapids that you couldn’t tell with essays? How was it for you writing it?

I started writing Grand Rapids right after publishing Surveys. Then I stopped working on it for a long time. When I was writing the content for Sleeveless and Artless, the time felt different. I couldn’t work on fiction back then, when the things that were going on in my world felt surreal. I mean, I think a lot of people have said this about that period. It was a huge shift in ways people around me were thinking, treating each other and acting. It was difficult to focus on fiction. I felt more drawn to writing about whatever was going on in my world. That makes it sound larger than it was. Sleeveless and Artless are pretty small in focus, about stuff that was happening to me and my friends. But I guess that’s what I mean. I felt drawn to documenting that. And now I’m no longer, I guess.

You’re no longer interested in that?

Not as much. Maybe that’s because so many people are doing it. Maybe younger people are better at it. I’m not as young as I was and it feels like it’s a young person’s thing to do. I’m not sure. Or maybe I’m just tired of doing it myself, and I’m interested in reading what other people are saying and thinking instead.

Perhaps it means you’ve evolved; your writing did. I recall that after reading Artless, you mentioned you were working on a second novel and I had no clue what it would be. Then I got in touch with you and your publicist and requested a galley copy. Reading Grand Rapids was very surprising and precious in the sense that I felt as though I had something I didn’t expect to have in my hands. I thought of Surveys and whether Grand Rapids was, in some way, a follow-up, or a sequel to it. I’m not sure, maybe that’s only my impression here.

It does feel like going back, especially because Grand Rapids is set in a place where I once lived, and it occurs during the time that I lived there. So it feels literally like going back in time for me, but also going back to writing a novel feels like this return to what I was taught in school. The form is fun for me again.

I love that you’re saying this. I love your “return.” My next question perhaps relates to this. Fiction or not, as I was reading Grand Rapids I got the feeling that it may trace some of your background. To me, the novel feels like the most personal work you’ve published as an author (except for the story in Sleeveless about you dating a garbage man!—that shit was hilarious and deep, Natasha!) [Natasha and I laugh]. I do wonder to what extent Grand Rapids was rendering your own experiences and memories as autofiction? How did you work with personal matter? Was writing the novel something like a process or a path to reconcile with something else?

Grand Rapids is definitely rooted in my own experiences. I think one nice thing about starting something a long time ago and then returning to it is that you have a distance in a few different ways. Obviously, I have distance from my own past experiences. I don’t write in a diary that much, so I don’t have many sources for my own history. And memories of things change a lot, especially if they’re talked over with friends. All these events start to change in value—not just for writers but for everyone. That idea was of interest to me when I was writing the novel. The idea that things from your past become more and less important to your current self, only because you then experience things that you would have never known you were going to experience—that almost became the story itself. Most of the actual story that didn’t happen, but there are parts that document the memory of a feeling that I had. I made it quieter than I could have. I could have gone really high drama, and maybe what I’ve learned from that experience of quieting things down is that now that I’m an adult, that dramatic stuff doesn’t seem so…

Realistic?

At the time, everything was devastating. Like all the breakups, and all the crushes, and friend fallouts, and whatever else. It was just devastating. And now, I’m thinking: was it really? And this is the experience of aging.

Maybe things in the past don’t seem so devastating because we have to deal with far more devastating things in the present.

Maybe.

As a reader, I was bedazzled by the depth of details and descriptions of Assisted Living, the nursing home in Grand Rapids, where Tess works. On the surface, Tess appears careless, but there’s a thread she develops with some patients, like that precious moment Tess grabs Genie’s hand: “Still, I shook Genie’s hand loose and held it. As I knelt to the ground, tears streamed down her face, quietly and without warning. I felt the backs of my eyes getting hot. Genie and I were holding hands in a fluorescently lit hallway, eyes in our laps, minds getting closer to the same pace. We each said nothing for what seemed like a long time.” What kind of research did you do in order to write the novel? Did you have to spend time in Grand Rapids, Newaygo, and Lansing to write the novel?

I have been to all these places because I grew up partially in Grand Rapids. As a kid, I moved there when my parents got divorced. So it’s not exactly the same timeline as the story, but I did live there during that time. I did work in a nursing home and it was my first job.

Grand Rapids spoke to me with its relentless wit and deadpan humor—quintessential to your writing. Aloof and experimenting with self-medicating, Tess’s observations become a blend of bleak and wry events. Her rendering is deeply affected by hanging out with her best friends Candy and Lauren, sleeping with addicts and working at the nursing home. There, one of its residents says, “If you take her, take me, too, and just roll me into oncoming traffic,” or another one about one of the patients, “Her husband was dead, but she talked about Mr. Ducote as if he was not. She was white-haired and delicate, and the RNs said that she was anorexic because she wanted attention.” Such deadpan humor and wryness seem interwoven into the heart of the novel. Is this something you consider to be your DNA as a writer? What is it? How do you think about it?

The aloofness? It is a part of me. Actually, remembering my first job kind of cracked something open. When I was young, I was around a lot of people who were dying, people who said that they wanted to die. The reaction from the staff was blasé because it had to be. That was where I learned how to work, one of the first places where I had a purpose. It must have made an impression.

After her mother dies, Tess, who’s 15, moves in with her aunt Norma and uncle John and their kids into her new bedroom “in a finished basement that stored Christmas decorations and snowboarding gear.” Clearly, Tess hates her new family. I mean, who wouldn’t? But there’s this particular space, in a very few sentences, where Tess approaches the reader directly—she’s aware of our presence—asking in one part: “Do you have any scars?” It’s like she wants us to know that connection she’s holding: “I can see you tidying up my background, my youth, in a phase, and no matter what it may be—working class, suburban, white trash, middle America—it doesn’t work.” She talks to us like we’re her pals. I love this nuance. Can you tell me about this?

I was thinking about how the memories of adolescence turn into these fables that you tell in the future. They don’t have to be real because eventually they’re not. What’s more important in the present is the mode of telling. The present-day narrator is maybe telling way too much about herself because she’s nervous. Maybe she’s on a first date. Maybe the person she’s on a date with asked her, “Oh, Grand Rapids, why did you live there? And for how long?” and then she recites this entire novel. Grand Rapids is not a small city, but it feels obscure to anybody living outside of America, and even most people from the Midwest tell me they’ve never been. Some people might not think it’s even a place. But if you know it, it’s one of those cities you can say so much about, and still won’t get it right. It’s not defined by its industry anymore, so maybe it’s postindustrial, but that doesn’t sound right because it’s not Detroit or Milwaukee: cities with giant failed industries. It goes back to the idea of being on a date, saying “this is me” and gauging a person’s reaction, knowing you’re not representing yourself quite right. That was a guiding principle of the book. Had you heard of Grand Rapids?

Well, at first I had no clue, but I Googled it and found it’s a city in Michigan.

There are other Grand Rapids.

To me, it sounded at first like the name of a huge waterfall.

Yes, exactly. To me, metaphors are always tongue-in-cheek. The idea that a coming-of-age story could be like a huge waterfall is just funny. I started out hating the title and then ended up liking it because it’s ridiculous to say that a young girl’s summer is the equivalent of grand rapids.

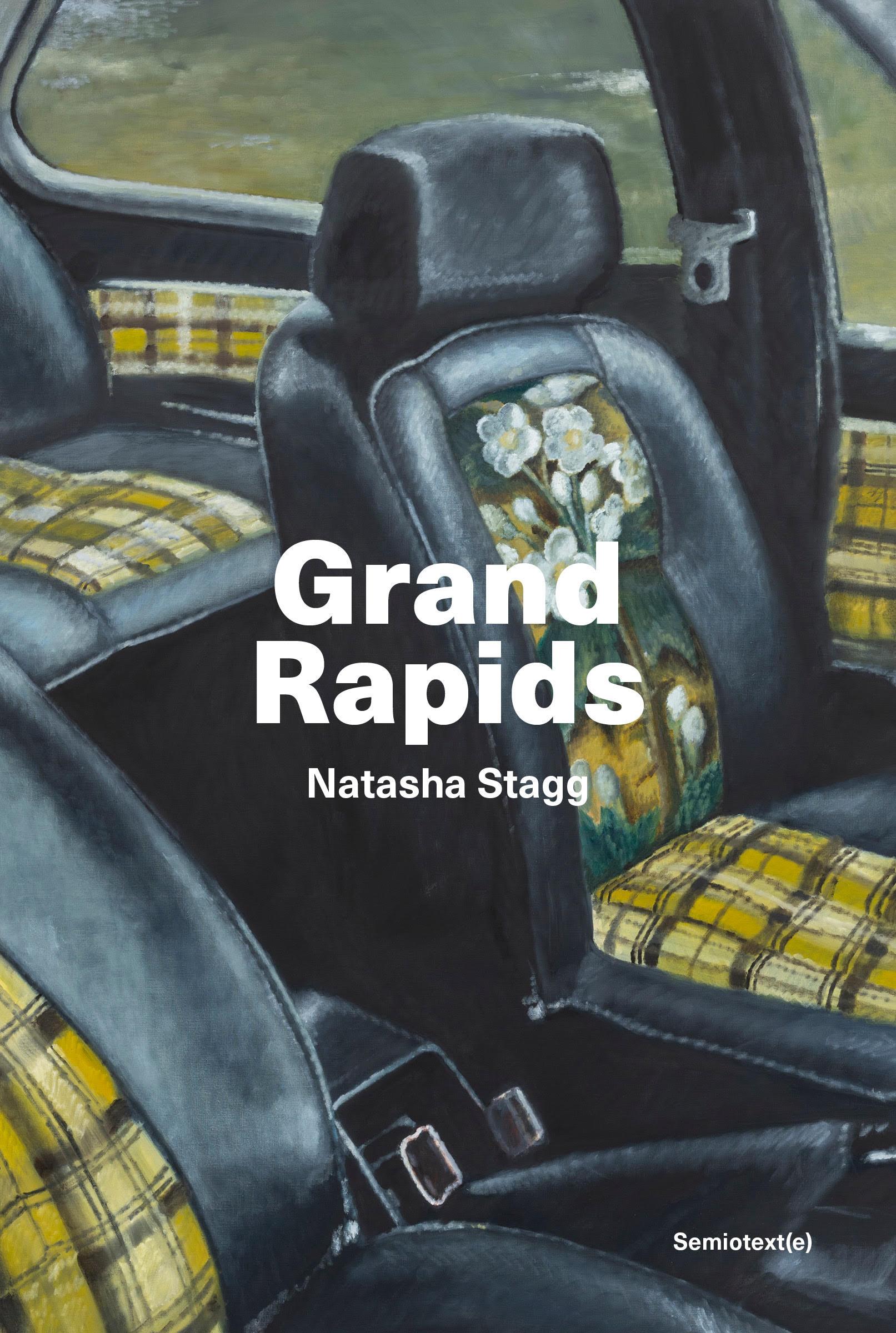

Yes, it’s also a very cryptic title, and to me, it also works marketing-wise. The novel’s cover—a painting by Issy Wood [Car interior / For once, 2019] is a great match with the title.

When I saw that painting, I thought: that’s what being in a car at that time looks like, when we think about it now. The way it’s painted is like a memory, not a photo.

There’s this dusty blanket-type feeling when you look at the car seats in the painting, which also made me think of the scene when Tess describes the drive into the dirt road, smoking, sweating, wearing the same clothes… My next question starts with the quote. Oh, perhaps, I have way too many quotes. [Natasha and I laugh].

That’s good. I need to jog my memory. [Natasha laughs]

“Once, after Candy and I got high on Robitussin and came home still tripping a little, I wrote in my diary that I was finally happy, which was sad. It was as if all the miserable things that were happening to me were so bad, they were forming a protective barrier around me, I wrote.” Tess reveals about her and friend Candy (who she is also somehow in love with). Tess says about her growing in Ypsilanti: “I was a full-on stoner back then, I’d say, unhappy with a lack of substances in my new school,” and “I had thought that the way to be cool was to show the least effort possible, but Candy, the coolest person I’d ever met, did everything, and looked down on anyone who didn’t.” I find this equally powerful and quaint because it hints toward the state of certain ennui—teens experimenting with stuff, avoiding sadness, advocating their own ways of knowing the world. When things that we’re told are wrong turn out not to be. Does this crystallize a kind of flipside for Tess?

When I’m writing these characters, I’m of course thinking about what types of conversations we had as kids that inform us as adults. How are we different from the generations below us? I don’t want to be a cultural critic again, but this idea of what makes our generation the way it is feels important to the novel. The way people characterize millennials and how we were raised; and how the older people around us at the time were looking at us and the media they told us to consume; the drugs that we were doing.

Natasha Stagg: Grand Rapids, 2025, cover, Semiotext(e).

I loved the part when Tess is introduced to PJ Harvey for the first time and says—“I’d expected PJ Harvey to be a man,” but then once she listens to it with Candy and her sister Cassie, it echoes inside of her. It’s also the moment Tess observes Candy’s dance, her body. She notices something carnal and intangible in a quaint observation. I think this is one of the most heart-aching sentences in the novel: “As I looked at Candy’s body, a ball in the middle of a carpeted floor, silent and faceless, the thought crossed my mind that she would one day die.” How did you think about writing Tess’ character? How did you imagine and construct her? She’s highly aware of life’s fragility—it’s all around her when her mom gets sick. She realizes something about herself then: “I was encouraged to stay away until she was ready. Ready to die, I after understood. When I die, I thought, I do not want anyone around to see it.” And I had to think, regardless of its fiction: Oh god, do I want that?

That might be one of the most teenage things there is: you can’t fathom dying because you’re so alive, and you rely on authority figures, wishing to be independent. As an adult, the goal shifts to finding people whom you can rely on. An adult might hope that when they die, somebody is there, making sure they don’t fall apart, alone. As a teenager, I probably hoped I’d die in a gutter somewhere, just slipping away.

Another image that was hovering around me intensely while I lived a couple of my days with Tess in Grand Rapids was the novel’s grunge aesthetics. I could smell the dirt road, cigarettes, and beer sweat. Although the story appears in the post-2001 World Trade Center attacks, it also made me think of Harmony Korine’s Gummo. There’s this emo grief, teen girl self-harm, trashy summer vibes to it—riding shopping carts, a very Americana summer, wasted youth—also Ethel Cain vibes to it. How do you relate to this? Were you consciously building the scenery up, or was it more memory-related?

My memories do end up getting informed by the movies and music I was consuming at the time, and later. Part of what forms adolescent memories is the distillations of that moment, made by professionals. It happens accidentally. Your own memories start to co-mingle with the media versions. In New York, I’ve heard people say, “You’ve seen the movie Kids? That was my life.” It’s a movie, so it was no one’s childhood, but watching it gave one the sense of being seen because it wasn’t a documentary, it was way more sensational. Memories end up mixing with the movie scenes. Which is no less true. Maybe it captured something real, and in its surreal way became more real than the material it depicted. I watched Gummo around this time of my life and felt it captured the wildness I felt then. That scene when they’re on a bridge over a highway resonated with so many teenagers because it’s an image of desolation, waiting for something to happen.

If Grand Rapids had a soundtrack, what would it be? PJ Harvey? Or someone, something else?

Good question. Yes, it could be all the songs that were popular at the time for us teens. I didn’t listen to much music that was new then. It was all eighties. The Cure, the Smiths, stuff like that.

In 2020, you quit both Instagram and smoking. After that, you started Selling Out, your Substack newsletter. How’s your post-Instagram life, and what do you think Substack offers that other platforms lack or don’t?

I already sort of hate what Substack has become. I wanted it to be where I linked to essays I’d published, so my friends would know, but it’s so different now. It’s where writers make money if they want to leave their corporate media job. I’m trying to keep up, but I don’t know if that’s good for me and my writing necessarily. I paywall everything. I do sadly love money and don’t have a lot of it, and there’s only so many copywriting jobs left in the world, especially with AI, so I’d like for my newsletter to make money if possible. But the highest paying newsletters are either the most productive in terms of getting people to click on shopping links, or very in-depth, near-daily essays, and I’m somewhere way off, not in between those, but some other place where I write little diaristic things, which will never make me rich.

How do you navigate writing about things, events, and people around you, which could be seen as a source of content? Didion wrote: “writers are always selling somebody out” (the title of your Substack). Have you thought of people—friends, boyfriends, girlfriends—as content? And if so, where does a writer draw the balance, the line?

I think about it nonstop. I could list everybody I’ve dated and how they reacted to me either writing about them or not. Because if you don’t write about them, they still get mad. It’s difficult enough to sit down and write, you don’t need another voice in your head.

Do you feel like you need to grow a thick skin when it comes to feedback? Like reading or not reading reviews?

I do read reviews. I think most people read reviews. I was talking with a friend yesterday about how he responds to negative reviews on social media. That feels so against my nature, to write a response, but then I wonder if I could be pushed to that point.

What’s the hottest gossip you’ve heard most recently?

Oh my god, I think I’m out of the loop. I love it as a question, though. I don’t know. Do I ever have hot gossip?