David Garneau. Courtesy of the artist.

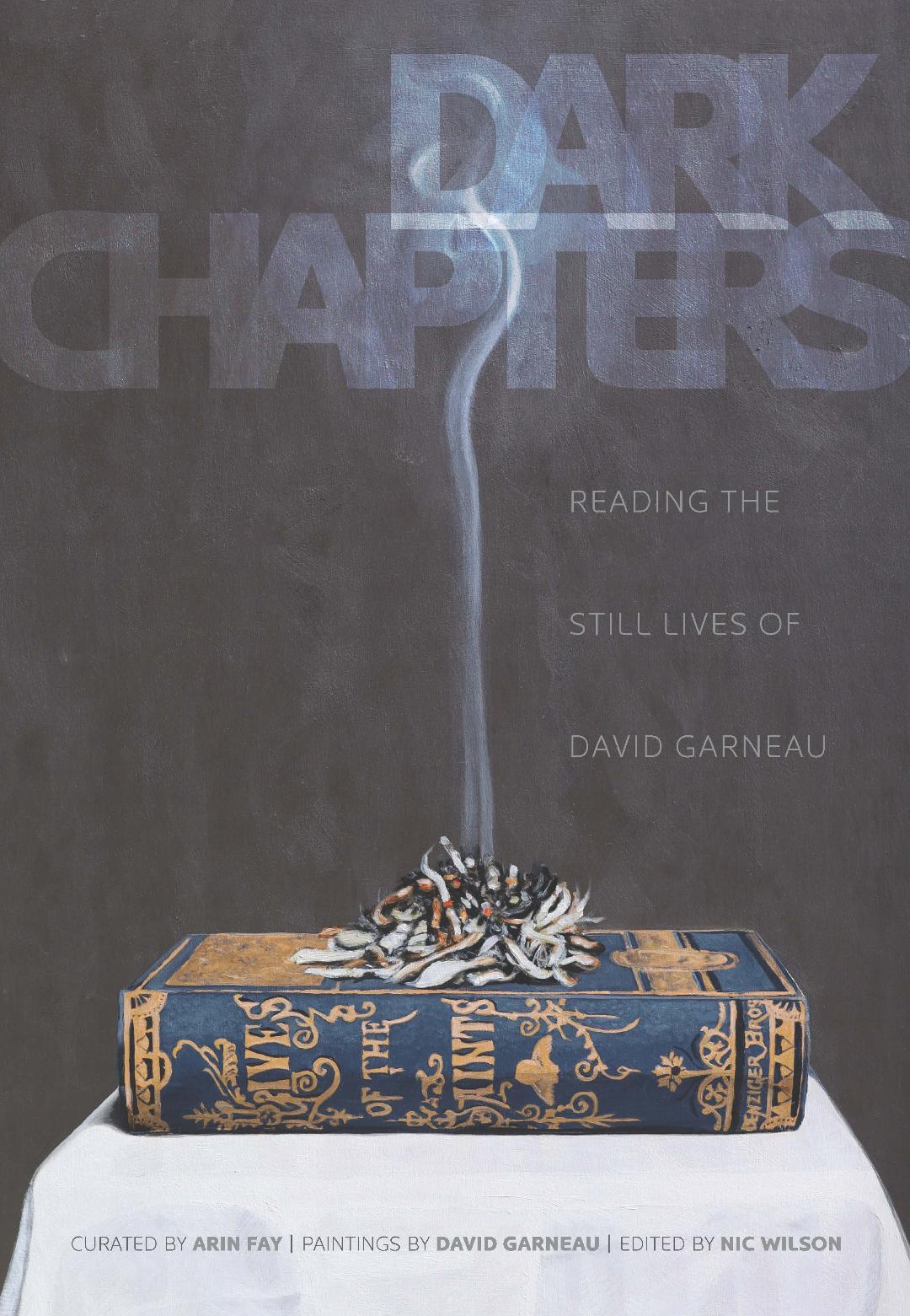

David Garneau first came to my attention when someone shared his 2013 painting Not to Confuse Politeness with Agreement on Twitter. The painting depicts Stoney Nakoda Chief Ubi-thka Lyodage (1874 – 1970) facing and shaking hands with an unknown young RCMP officer. Above the officer’s head is a square. Above the chief is a circle. I thought it brilliantly represented the challenge of (re)conciliation. So when I was invited to review his book Dark Chapters: Reading The Still Lives of David Garneau, I leapt at the opportunity.

Garneau is a painter, writer, curator, and professor who currently creates metaphorical still life paintings that express Indigenous issues through common and uncommon objects. He was awarded the Gabriel Dumont Silver medal for outstanding service to Métis people (2025); the Governor General’s Award for Outstanding Achievement in Visual and Media Arts (2023); and was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. As a Métis artist and public intellectual, Garneau has been leading the charge in complex conversations around the nuances of Métis identity and the politics of Indigeneity, Indigenization, and non-colonial aesthetics.

Our email exchanges took place both while he was at his office/studio at the University of Regina, Saskatchewan, and while he was a mentor at the Kapishkum: Métis Gathering Visual Arts Residency at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. During our conversations, Garneau recounted the complexity of his position as a white-passing Indigenous artist/scholar working with universities and art galleries as they struggle to become non-colonial institutions. He also discussed the challenge of balancing the desire to be an individual artist with the responsibility of being a Métis man and an advocate for Métis heritage and culture.

Dark Chapters encapsulates what Justice Murray Sinclair described as “one of the darkest, most troubling chapters in our nation’s history”—the Indian Residential School system. Garneau attended TRC gatherings in Montreal, Vancouver, and Edmonton, among others, and was deeply moved in positive, negative, and still unresolved ways. For Garneau, TRC, the spectacle, was focused on individual truths and trauma rather than collective experience; premised on the metaphor that this intergenerational genocide in slow motion was merely a chapter that could be contained and closed. These experiences inspired his Dark Chapter still life paintings.

My work is a series of problem solving and vision broadcasting with its own internal and mysterious agendas. I live as if it is consequential work, as if there are forces within and without that guide my hand and mind. It may be a fiction; I live there too.

About six years ago you began painting still lives for your series, Dark Chapters. Currently, there are over 300 paintings in this series. What was the inspiration for these paintings? And, why are you continuing to add to the collection?

Still life painting has been an enduring, but until recently, intermittent part of my practice. I turn to it when stressed. For example, my partner, Sylvia Ziemann (also an artist), and I had our first child, B, 29 years ago. Our small apartment necessitated making modest work. I painted scenes of paint tubes facing off against baby soothers, books in wood vices, and shelves lined with books and disposable diapers. The paintings expressed the tension I was feeling between wanting to be a good father and my desire to also make art and write. A few years later, following a death in the family, I painted skulls.

It wasn’t until 2016 that I was motivated to make a deeper commitment to still life painting. That summer, along with Rebecca Belmore and Adrian Stimson, I was a lead artist at the o k'inādās Indigenous Summer Intensive Program at UBC in Kelowna, BC. I assembled books, twine, rocks, sticks, and other natural objects to produce thirty-five metaphorical compositions that echoed my inner and outer struggles. Themes included the complexities of being a white-passing Indigenous artist/scholar; of working with universities and art galleries while they struggle to decolonize; of wanting to make personal artistic expressions while also feeling a responsibility to make Métis art.

European art academies ranked still life painting at the bottom of their aesthetic hierarchy, after history painting, portraiture, genre painting, and landscape. Most still life artists settle into this niche and confine themselves to the reproduction of homey things as they are. However, some, such as the Dutch vanitas painters, exceeded expectations and infused the mundane with rich metaphors. Others, notably Picasso (Cubism), Johns, and Warhol (Pop), turned to still life to hone their formal and conceptual experiments before engaging “higher” genres. My still life turn was based on a desire to make small works that express big ideas. Large paintings took too long, and I was brimming with images and experiments. I wanted to attract viewers with familiar objects rendered in an approachable and pleasing manner and then lead them to consider unsettling content.

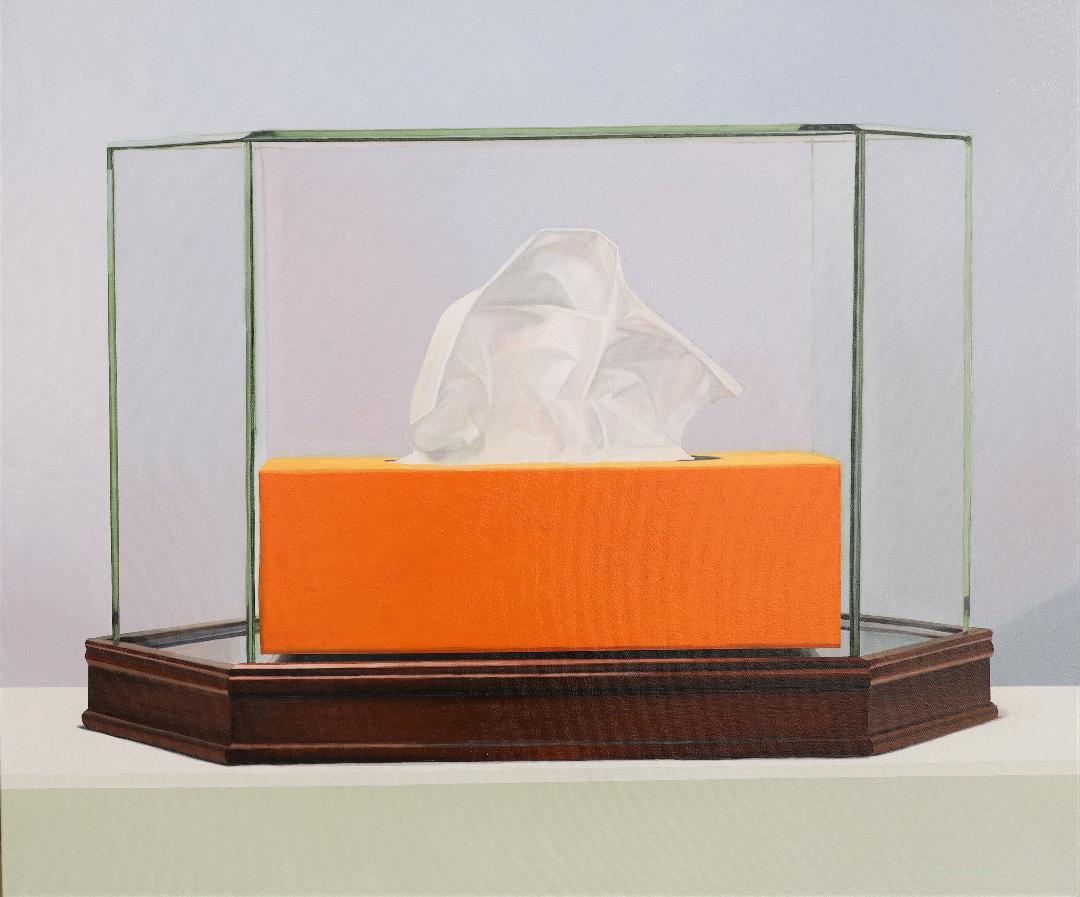

During the 2010s, I was writing about Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation efforts, about Indigenous belongings in colonial heritage museums, and about contemporary Indigenous identities. I wondered if I could express these complex experiences, debates, and ideas through visual metaphors. In Healing Alone, a split stone is held together with duct tape. Ally Tear Reliquary (TRC Archive. 2014, 1.01a) shows a box of tissues archived in a museum vitrine. It refers to the tissues issued to attendees at the large TRC events, but also to the public displays of Indigenous pain. Indigenous Academics shows five Indigenous authored books arranged on the edge of a shelf. Unsupported, they are about to spill.

I figured the project might run out of steam after a year. Six months in, Covid hit. I retreated to my small home studio, where I remain, happily. The work persists because it is a fairly novel approach. There is plenty to harvest from this neglected berry patch. It also endures, in part, because I have committed to post a new painting every week on Facebook. This keeps me disciplined but it also reaches folks who might not read my academic writing or enter a gallery. The online feedback is motivating. The reception lets me know when I am making sense, and not.

Your book, Dark Chapters, launched on March 25, 2025. The beautiful book invited seventeen poets, fiction writers, curators, and critics to engage with your paintings. Your “still lives” appear alongside poetry, fiction, critical analysis, and autotheory written by such distinguished contributors as Fred Wah, Paul Seesequasis, Jesse Wente, Lillian Allen, Billy-Ray Belcourt, Larissa Lai, Rita Bouvier, and Susan Musgrave. Why did you assemble such an impressive lineup of folks to write about your paintings when you are a very accomplished writer and could have written about them yourself?

My practice oscillates between art making and critical writing. I love the interplay of text and image—which is why titles are essential to my paintings. I have an MA in American literature. The last proper literature paper I wrote concerned hypotyposis, which is the description of images created in the mind when you read. I was interested in a reverse ekphrasis. Instead of writers rendering visual art into text, I wondered how visual artists might write about the images that came to mind when reading literature from within a visual art imaginary. Now, I am interested in how still life paintings, abetted by their titles, can produce meanings, associations, and feelings that are not only personal but also inter-subjective. While I strive to make legible visual metaphors—that is, paintings that make collecting sense—I also want to co-generate meanings that exceed my intentions.

I could have written a book that explained each of my paintings. However, authorial accounts often stifle alternate readings and the production of new knowledge. I invited creative writers, curators, an anthropologist, visual artists, poets—deep thinkers and feelers I know and admire to choose a work or two and respond in text as they saw fit. I was excited to see what others would make of pictures, what images (hypotyposis), ideas, and experiences they would co-produce, and how this might fuel further images, texts, and conversations.

In the past month, I have attended book and exhibition launches in Montreal, Toronto, and Nelson, BC. In each case, several of the writers read their texts next to the paintings. The Regina launch featured twelve of the authors. In every case, I felt the urge to run to my studio. The writer’s generous insights co-produced mental images that demanded to be painted. I also marvelled at the rich themes that run through their texts: on allyship, interpretation, empathy, identity, and image/text tensions.

You and I have discussed how your understanding of these paintings differs from the written responses included in Dark Chapters. So, how have these new interpretations caused you to take a second look at your work and the meaning it conveys? Do you have one or two specific examples you would like to share?

“Confession” shows two stones with a book between them. I hoped the title would remind viewers of the Catholic rite of confession, and lead to associations documented by the TRC. Replacing people with objects can free the imagination. Fellow Métis, Rita Bouvier by-passed the sinister Catholic reading and instead saw the book as a brick wall dividing the younger stone/child from the stone/Elder. Her generosity made my eyes water. Rather than see an oppressive and potentially abusive situation, she saw a youth and Elder separated by the wall of colonial schooling and institutions. Her poem imagines the stones scaling the wall, sitting on the top, enjoying fellowship and a more comprehensive view. I love this! She enters the painting as an artist, engages the hypotypotic imaginary and rearranges the composition to suit her desire. It makes me want to make a co-responding painting.

I come to ideas for these paintings in several ways; mostly in dreams and meditative walks. I write them down until I am ready to develop them. Three times a year, I take three or four days in the studio where I simply handle objects, put them in play with each other, compose them as pictures and not-yet-verbal concepts. Once a combination appears striking and metaphorically suggestive, I photograph it. There can be a considerable lag time between conception and completion—sometimes a year or more. However, the news will often stimulate me to complete a painting—from conception to titling—in less than a week.

I have inklings while composing, but meanings are unsettled until the finished painting is christened. Titling is a distinct operation, a philosophic and poetic one. I approach titles with caution and care, as they both open and restrict an image’s reception. Christening finishes the authorial stage of the work. “Grandfather Contemplating Western Ocularcentrism” shows a round rock reflected in a mirror. The title invites the viewer/reader to contemplate Indigenous extensions of animacy beyond the quick, and Western restrictions. You might wonder about the line between recognition and projection. You might also think, as Anthropologist David Howes does, about the contemporary privileging of sight over other senses. In his essay, Howes unpacks these ideas and links the painting to ideas in anthropology and Indigenous scholarship that I was unaware of. I appreciate that he shows that paintings can not only illustrate theory but also generate and perform novel ideals and associations. He both ‘gets’ what I am doing, and also extends the meanings beyond my intention.

Ally Tear Reliquary (TRC Archive 2014, 1.01a), 2023, 76.5 x 92cm, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

The Troubling Ability to Paint During Genocide, 2025, acrylic on canvas, 48” x 36”. Collection of the artist.

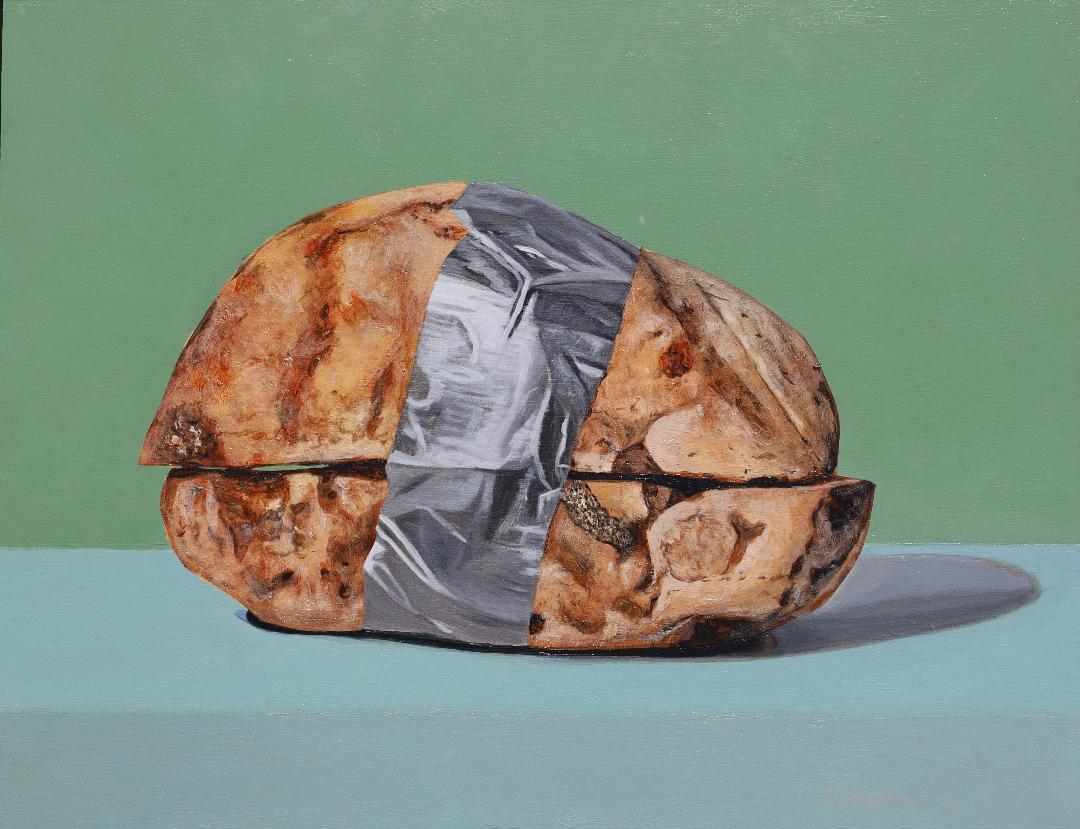

Healing Alone, 2021, 36 x 46cm, acrylic on panel. Collection of the MacKenzie Art Gallery. Courtesy of the artist.

Book cover for Dark Chapters. Cover art: Syncretism II, 2023. 61 x 45.5cm, acrylic on panel. Courtesy of the artist.

Your still lives are the antithesis of traditional European still lives—particularly, the Dutch painters of the 1600s whose use of dark colours and inclusion of exotic flowers, fruits, and fabrics represented new wealth acquired through colonization. Your still lives, on the other hand, are bright, filled with light and colour. The images you paint represent knowledge, spirituality, culture and what has been lost to colonization.

You create impactful minimalistic images by combining everyday objects like books, bones, teacups and mirrors with a Métis sash, a stone hammer and a braid of sweet grass always positioned in a precarious manner which is reflective of the complexities of contemporary Indigenous experiences.

How did you come to embrace being a Métis artist? And, how are your paintings distinctly Métis?

For many years I worked in an appropriative mode, riffing on Western art history and popular culture, especially comics. Between 2006 and 2019, I tried to devise a contemporary mode of Métis visual art that built on Métis material culture. My ‘beaded’ paintings combined landscape painting, portraits, maps, and other scenes with an overlaid screen of painted beads/dots. These works were meant to engage Métis folks and to be a display of Métis visual survivance and innovation. I concluded this work with the Tawatina Bridge, a huge public art project for the City of Edmonton (my hometown) consisting of hundreds of paintings affixed to the roof of a pedestrian bridge.

Exhausted by that big job, and feeling I had nothing more to say in the beaded style, I turned to still life. The realism of the Dark Chapters paintings is not customarily Indigenous, but the content is. They show obvious signifiers of Indigeneity—braided sweet grass, feathers, stone hammers. And of Métis-ness: sashes, flags, and bannock. But they also include odder items and strange combinations—such as nooses and Hudson Bay blankets, teacups and fish heads, handcuffs and bricks—that have special associations for Plains Indigenous people. The depth of your feelings and meanings with these paintings depend on your experience and familiarity with Indigenous history, ways of knowing, being, and doing. My greatest pleasure comes when folks become familiar with my visual vocabulary and allusions. They then read across works, find recurring objects but in new environments and relations that change their meanings. In addition to being a book, Dark Chapters is a travelling exhibition. Its first stop is Nelson, BC. At the opening, I held a talking circle with sixteen local Métis. I was amazed and gladdened that they were able to read and extend this content. The paintings triggered rich associations and group conversations.

In these paintings, books represent written knowledge, book learning, educational institutions, and colonialism more broadly. However, they are not purely colonial. Much of the work concerns the tension Indigenous academics feel concerning settling Indigenous knowledge in books and classrooms rather than learning with the land. Many Elders want the knowledge they steward preserved in books because they fear it might be lost with their deaths. However, they also fear that books might replace them and displace authentic forms of Indigenous learning. They lament that they must archive this knowledge when it would be better if traditional modes of transmission were maintained.

Rocks in these paintings are often grandfathers and represent land-based teachings. Though sometimes they figure Indigenous people, especially students and professors, rough rocks often suggest rural or less colonized Indigenous folks. Smoother stones may suggest urban Indigenous people and folks less rough around the edges. Apples are associated with education and medicine. They also refer to the pejorative leveled on Indigenous folks thought to be assimilated: red on the outside and white on the inside.

I’d like to focus now on the specific Métis sash that often appears in your still lives including, Maternal Influence, where you use a very colourful sash outlined in black.

Métis adopted and adapted the sash from their French fathers. It was useful as a belt but also as a signifier of Métis presence and difference. Dark Times is a classic Assomption sash with the red border replaced with black to represent the land loss, dispersal, oppression, and silencing that followed the 1870 Red River Resistance and lasted until recently. Most viewers will see a Métis sash but not know this meaning. I like that much of my content is a slow burn. Many Métis will know what it signifies. But I want to deepen their understanding. In Woven and Free, a folded sash is sandwiched on a shelf between four books. The whole is further bound by twine. This suggests Métis bondage by colonial institutions but also our complicity with these spaces and ways. However, I see in the sash an expression of Arthur Koestler’s notion of the holon, that everything struggles between being “its self” and being part of a greater whole. Sashes are tightly woven, but their ends are loose, unbound. Métis were called by the Cree Otipemisiwak: those who rule themselves. Métis are ruled, have an order, but it is self-generated. We are a collective who value individual freedom. I hope by this painting to add new meanings to sash teachings.

In the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reports, Justice Murray Sinclair describes the residential school system as “one of the darkest, most troubling chapters in our nation’s history.”

Why did you choose this dark historical chapter to be the theme of your exhibition as well as the title of your book?

Beginning in late 2011, I was involved with several academic researcher teams working on issues arising from the TRC. Before getting to what we described as creative conciliation artmaking, curatorial, writing, gathering, and other projects, we attended many TRC gatherings, including the spectacles in Montreal, Vancouver, and Edmonton. They were heart-wrenching. Even before going to those events, I wrote “Imaginary Spaces of Conciliation and Reconciliation: Art, Curation and Healing” (2012) outlining the incongruity of trying to have reconciliation before establishing conciliation.

I was deeply moved by the gatherings in positive, negative, and still unresolved ways. Much of my writing from that time concerned the language of the TRC. The preference for “telling one’s truth,” for focusing on individual rather than collective experience, of a desire to render these experiences and events as a “chapter” that can be contained and turned. Most of the images attached to the TRC appeared more illustrative than provocative. I wanted to extend my written considerations to painting. I hoped to produce something beyond visual triggers to familiar meanings. Most of my paintings are unsettled, even contradictory. They embody my mixed thoughts and feelings about most things.

The titles chosen for your works, including Métis in the Academy and Smudge Before Reading, ask viewers to consider the mixed influences and loyalties faced by Indigenous students and scholars. Still other paintings explore colonialism, vertical and lateral violence, Christian influence on traditional knowledge, and museum treatment of Indigenous belongings as in Art and Violence I.

These are issues that mainstream Canadian governments, institutions and citizens are reticent to have meaningful, actionable dialogues about. Justice Murray Sinclair knew education was key to reconciliation, stating, “Education got us into this mess and education will get us out of it.”

How could Dark Chapters be the catalyst that initiates and spreads the necessary conversations that ultimately will educate Canadians about residential schools and the intergenerational aftermath?

As a teaching professor, I want to join in Justice Murray Sinclair’s centering of education. As I am of multiple minds about most things, his claim is followed in my mind by Audrey Lorde’s "The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house." My agreement with Sinclair would need to extend education beyond schooling. As part of the book tour, Dark Chapters has included public conversations with some of the authors and me. But they have and will include other Indigenous folks, colleagues and artists, local to the community in which the book is launched, but who did not contribute to the volume. In addition, each exhibition includes talking circles with Indigenous folks. The first one was in Nelson BC where I met with sixteen local Métis. Rather than me explaining each work, I introduced the project and then asked this multi-generational group to choose pieces they would like to discuss. If this dialogue is education, then Sinclair and I are in agreement.

I did not imagine that the Truth and Reconciliation project would lead to genuine change, become an industry, last beyond a few years, or that efforts of (re)conciliation would permeate so many aspects of institutional and daily life. It has been encouraging, overwhelming, and complex. It is the complex aspect that I want to linger on. While I have played small roles in institutional and policy change, I hope my paintings are less productive, smoldering. I want them to be in permanent collections in museums and art galleries, to be published, to be on the covers of books to illustrate papers, book chapters, etc. To be taken up and employed as required. Because of their unsettled nature, I think they will continue to activate beyond my intentions and the intentions of those who adopted them. I hope they parallel Indigenous identities and persons, always changing, never settled. While they can be made to serve settler folks, most are messages sent in code to Indigenous folks. They are intended to help them picture their possibilities beyond the rote and the scripted.

Why are you continuing to create new pieces for this series that are finding space in smaller Canadian galleries like Regina’s Assiniboa Gallery, Montreal’s Art Mûr and Toronto’s Gallery Gevik?

I am a restless artist and thinker. I jump from project to project and style to style. Sticking to one project for six years is a refreshing change. While I feel the urge to take up figure painting, or return to the beaded style, I keep coming up with new still life ideas. I also keep challenging myself with technical problems. The paintings keep increasing in size. While most are around 24” x 18”, about half are swelling from 4’ x 3’ to 5’ x 4’. Posting a new painting every week on Facebook is taxing. While I can complete a small one in 20-30 hours, large ones such as The Museum and its Discontents (after Holbein and Luna) took all of last fall.

A big part of my mission is to have these works live beyond my studio and private homes. Many are collected by public institutions. Shifting the private and public visual imaginary regarding Indigenous peoples requires that the work be in a variety of venues. Public galleries, commercial galleries, online, in publications.

We’ve talked about the fact that the writers included in Dark Chapters have given you new interpretations of your paintings. In fact, you are contemplating creating a new series of still lives based on those interpretations. Would you consider exhibiting the pieces side-by-side in a future exhibition?

At the Regina book launch, I mentioned making a painting responding to Rita’s word image and perhaps to every entry in the book. I’ll respond to Rita this fall. I can also see visual puns extending Fred Wah’s spine wordplay and Howes’ play on ‘still’ and ‘living.’ Cecily Nicholson’s contemplations of glacial erratics have stimulated many images that need painting. Paul Seesequasis’ evocation of the trapper, scholar, Marxist, labour and Métis organizer Jim Brady—and my relative—is a call to celebrate him in more paintings. Peter Morin has already had me take greater care with the air between things in my compositions. I thought I was through with my critique of the academy. Tarene Thomas’ poem has let me know that I have just scratched the itch. Jeff Derksen, Larissa Lai, and Arin Fay have, in their state of the discourse contemplations of allyship, made me return to the studio to think more deeply on this. So, yes, this book, and our subsequent public conversations, have set my imagination on fire.

You live on Treaty 4 lands which include Regina and that city was originally known as oskana kâ-asastêki in Cree which translates into “pile of bones” referencing the bones of plains bison that were found around Wascana Creek. The name was changed to Regina in 1882 to honour Queen Victoria when a British settlement was being established. You recently started painting oskana, piles of bones, and discovered a connection to Palestinians. Can you describe these similarities and why you continue painting piles of bones?

Bison were central to Plains cultures. Their genocide paralleled the people. I haven’t been able to revive and celebrate the living animal quite yet. I am still contemplating the disaster. Living in Pile of Bones rather than, say, Buffalo Achers, will do that to you. Oskana is said to refer to the bison bones that were collected and shipped east to be made into fertilizer, charcoal, and buffalo bone china. Others say that during smallpox epidemics Plains folks piled the bones of the infected in piles along Wascana Creek. A few years ago, I was gifted a box of bison bones. At first, I wanted to simply make piles of bones to echo the name of my adopted home. At the same time, I was making and painting piles of rubble. I think they were about my aging body and a recent injury and surgery. They began to evolve while I watched the invasions of Ukraine and Gaza. These “shrapnel” paintings soon converged with the bison piles to include bones, bricks from an old school, rebar, and bits of cloth. The most recent one, The Troubling Ability to Paint During Genocide, has been seen by some to draw a parallel between the Gaza and Plains genocides. I ruminate, following Goya, on how horrors produce both monsters and art. This work perhaps best reflects my perpetually conflicted interior state. How does one dare pleasure while terrors and injustice exists? What good is art making in the face of existential threat?

Can you leave readers with something to look forward to, some glimmer of hope in our own dark times of authoritarian governments run by oligarchs who are driving the climate crisis and want to stamp out the last vestiges of solidarity, knowledge, free speech, peace and frivolous expenditures like the arts?

What is the uplift? I live in the republic of art and in the province of as if. I live as if my art and life mean something. I am thrilled when my work makes meanings and impacts, inspires, I do what I can to foster this reception. I don’t make art for art’s sake, but its making is not dependent on proscriptive outcomes or authorial desire alone. My work is a series of problem solving and vision broadcasting with its own internal and mysterious agendas. I live as if it is consequential work, as if there are forces within and without that guide my hand and mind. It may be a fiction; I live there too.