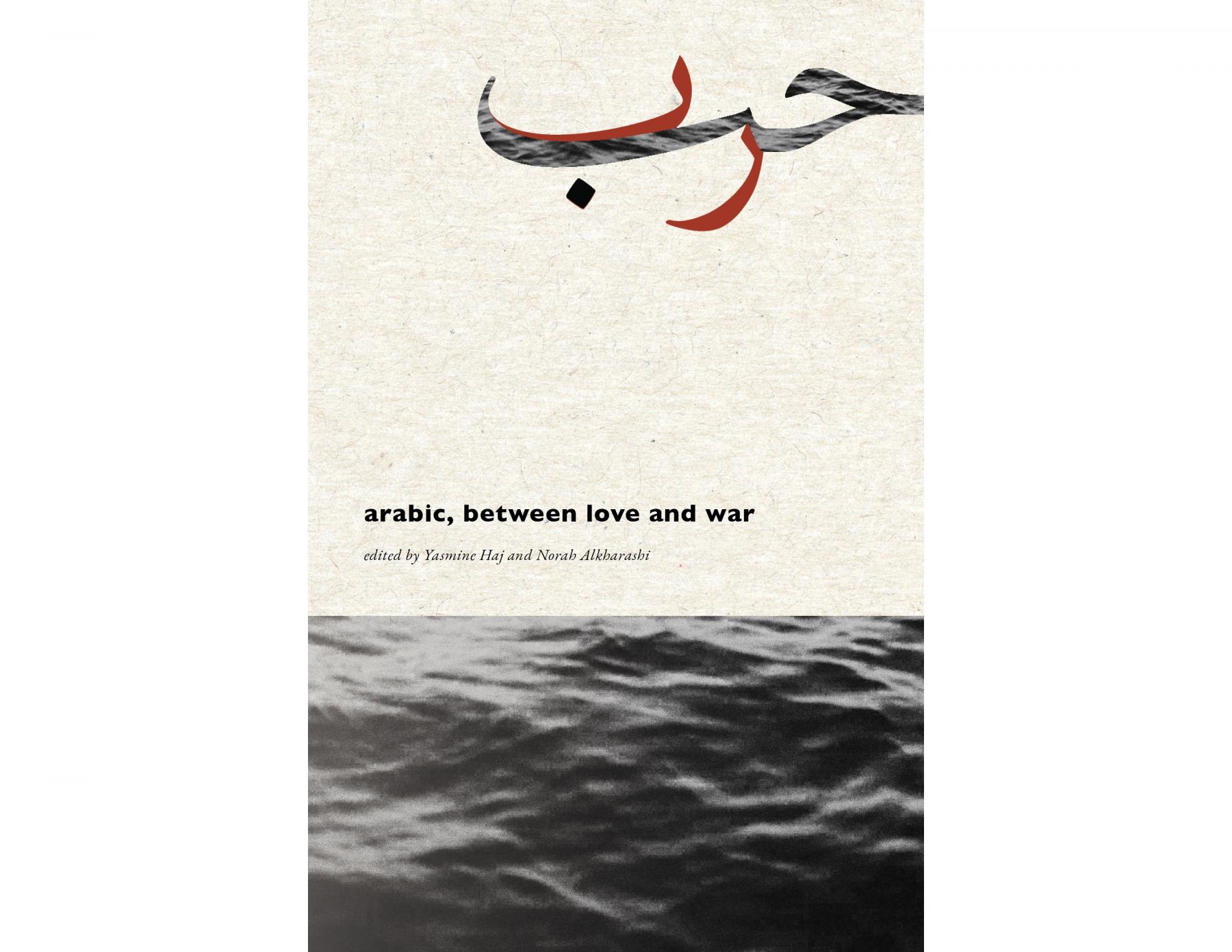

Arabic, between Love & War, Book Cover.

Arabic, between Love and War is a book of Arabic poems side by side with their English translations that resists the pitfall of "humanization." It is part of trace press' process-based publication series, where each publication arises from a number of creative workshops. This collection in particular arose from workshops held between 2022 and 2023, facilitated by the editors Norah Alkharrashi and Yasmine Haj.

Literary translation and "humanization"

The publication series explores the challenges of writing and literary translation. Literary translation raises a number of troubling ethical questions in general, but such questions are especially salient when dealing with a language/people and geopolitical context laden with existing presumptions and politically-charged narratives.

In "Between Impossibility and Necessity," an opening section of the text, editor Norah Alkharrashi writes that the art of literary translation is both impossible and necessary. Alkharrashi writes of the difficulties of translation, especially of poetic translation, "which, being among the most refined and expressive of literary forms, is expected to have myriad and complex nuances." Scholars of comparative literature, who engage with literary texts across cultural, geographical, and linguistic contexts, have long grappled with the limitations of literary translation. Such awareness has been enriched by the recent growth of critical translation studies, itself shaped by decolonial, antiracist, and feminist thought.

When we're translating works into English from a language like Arabic, with its unique history and present-day geopolitical context, clear power dynamics are apparent. In Perfect Victims and the Politics of Appeal, Palestinian poet Mohammed el-Kurd writes that if we want to address the empire, we are often required to be fluent in its language. But el-Kurd points out that this expectation is vastly asymmetrical: "We are often admonished by critics who are illiterate, or purport to be illiterate, in our language."

Translation cannot occur in a vacuum. It begs the question from the outset: who are we translating for? Suneela Mubayi, translator and independent scholar, wrote in an essay titled "The Temple Whore of Language," that translators who operate in a broader literary market are subject to considerations about the relevance of their project to the contemporary global North reader.

In such a context, translation often risks slipping into a project of "humanization" because of the insidious temptation to explain to an audience that might be (or pretends to be) "illiterate." El-Kurd writes about how humanization "diverts critical scrutiny away from the colonizer and onto the colonized."1 Writing from a Palestinian perspective, El-Kurd points out that such a framework lacks serious power and material analysis and accepts the Israeli framework of racial and socioeconomic domination as "applicable if need be." The limitations of this humanization project are manifestly clear: just look at the repression of free speech on college campuses across the Western hemisphere, the threatened deportation of pro-Palestine activists in the US, and the characterization of pro-Palestinian marches in Canada as "hate marches." Indeed, the problem doesn't seem to be how Palestinians exist, but the fact that they do.

The consequence? According to el-Kurd, the majority of Palestinians "fail to survive dancing on land mines." In other words, they fail to humanize themselves and "the world abandons them."

At the beginning of this collection, editor Yasmine Haj is emphatic that this text is not meant to humanize or to persuade. In the opening "To Speak to Each Other," she suggests that engaging in translation in community can open up a world of knowledge and expand language between individuals, a way to deepen vulnerability with one another, as opposed to the way we might "perform" for an indifferent audience.

"Speaking to each other": the poems in the collection

The poems in this collection embody the spirit of this sentiment. They engage with the clichéd notions of "love" and "war"—concepts which, stated so explicitly in the text, make one immediately wary of the way Arab writing might be flattened or pigeonholed—but do so in ways that are expansive and playful.

Arabic, Between Love and War is divided into three sections: "love," "intervals," and "war." The categories themselves are unstable: the poems in the "love" and "intervals" sections are haunted in no small measure by images of war and oppression. The "intervals" section of the text engaged with the limits of language, not just compelling for someone like myself reading a text in translation to think about, but also a fundamental hurdle for writers and/or translators of those very poems seeking to put into words the unspeakable. In "College of Midwifery," a poem about a midwife named Najat (Arabic for "refuge" or "survival"), Mayada Ibrahim translates the words of Sudanese poet Najlaa Oman Eltom. The poem states:

On the path to progress, there are electronic checkpoints

if a metaphor walks through, it bursts into flames

for this reason

one cannot walk in a maze made of one word.

The "electronic checkpoints" point to the impossibility of language, which "bursts into flames" in the face of this political reality. Language also risks constraining the imagination: "progress" is "one word," an all-encompassing, collapsing word that fails to capture a rich maze of reality, merely indicating "electronic checkpoints" along a linear path.

I am wondering what it might do for us, as readers of translated works and for publishers of such works, to think about this extra step of familiarity as an ethical obligation. Poetry cannot dismantle the imperialist forces that contribute to the oppression of racialized and colonized peoples globally. The editors of this collection are under no misapprehension that decolonization can occur by way of metaphor.

My favourite poem in this section was "Galeo/li." It is a playful and at times absurd poem, originally written by Lebanese poet Samar Diab and translated by Nofel, playing with inversions ("if it rotated…"), and imagining different realities. This inversion in particular stood out to me:

If it rotated, my dear,

the dead would have fallen from their shrines like raindrops

and we would've ambled beneath them talking about love and

desire. The young a gentle drizzle, the rest a heavy rainfall.

We would've awaited them every season for crops not to rot…

Here, the dead become replenishing, keeping the crops from rotting. But how much of an inversion is this really when the dead have always nourished the resistance of the living? Juxtaposing this so-called "inversion" with the others underlines that maintaining hope when faced with the death of loved ones should not be taken for granted—the poet conceptualizes it here as a radical act of imagination.

But not all the poems in the collection are hopeful. In the "intervals" section in particular, many of the poems howl with loneliness. In "A Lonely Man Walks on the Bridge," another poem by Diab, also translated by Nofel, the narrator of the poem recalls walking alone on a bridge "without lust, without memory." But this lack of connection fails to protect him from a deep, echoing heartbreak: "Why does my heart sting this much," he asks, "I, who want nothing?"

A beautiful counter to this is a poem from the "war" section. "Their Blood," originally by Palestinian poet Ibrahim Nasrallah, and translated by Eman Abukhadra, illustrates just how expansive one's connection to one's homeland and loved ones can become, even after one dies. In this poem, the blood of martyrs is everything from "their mosques… their churches, / windows to their homes…", to "their land's birds and its winds." The poem points to the interconnectedness not just of man to man, but man to his environment: the martyrs "left no trees to reproach them" but are "friends of the sea, friends of the river, the eyes of olive trees, the anemone flower, the greenness of trees, and the childhood of rivers." They are "a Mecca for poets / and a reserve for the poor, / a road at dawn, / a laugh within the rocks…" The poem moves from the very tangible and physical plane to something always a little out of reach, like "a laugh within the rocks." Through the use of these various metaphors, the poem offers an utterly shattering depiction of grief. It also beautifully illustrates the Palestinian cultural value of ṣumūd, which generally translates to "steadfastness" and reflects rootedness in the face of oppression. It can have both a more so-called "passive" connotation, reflecting the preservation of life and one's homeland (not a passive endeavour at all, although it seems to often be framed as such), and a more active, dynamic component that encompasses active resistance against oppression.2 This poem illustrates how one's deep connection to one's land is alive and felt among the living, both human and non-human, long after the martyrs are gone.

"Speaking" to whom? an outsider's perspective

Reading the collection cannot be separated from the creative workshops that led to the translated works, as well as the community readings in which the translators shared the collection over and over again with others over Zoom, transcending borders and timezones, and serving as a momentary reprieve to the endless gaslighting and distortion of the Middle East by Western politicians and in popular media.

Something new and effervescent is generated through this process. As a non-Arabic speaker, I cannot access Arabic poetry without English translation. But also, as a non-Arabic speaker, I remain generally oblivious to the shades of meaning Arabic words/lines can hold. As a reader, I remain an outsider to the rich literary discussions and back-and-forth editorial decision-making that occurred before this text was finalized, printed and delivered to me. While I have always considered myself in solidarity with Arab peoples (and thus, would ordinarily consider myself part of the "community" that Haj spoke of in her introduction), reading this text in English did not completely remedy those feelings of being an "outsider," nor did attending the community readings. In fact, at times, I felt quite "illiterate."

I don't doubt that's how the translators themselves felt—many of them members of the diaspora, translating the words of writers who came from contexts they would never know in the same way, and even if they did, might struggle to put into words regardless. They, too, likely felt the tension and discomfort of being an "outsider," while at the same time understanding the necessity of their participation.

To me, the genesis of the text and the way in which trace press encouraged its reading signals a fundamental departure from the Western obsession with "fidelity" in translation, where the goal has always been for a translated work to be as faithful to its original as possible, to this more rich and unsettled model of "familiarity."3 Reading the text in English and attending the community readings granted me greater familiarity with the worlds of the translators and introduced a beating heart to their own works of creation, something I might have overlooked had I read this text solely in a solitary manner.

I am wondering what it might do for us, as readers of translated works and for publishers of such works, to think about this extra step of familiarity as an ethical obligation. Poetry cannot dismantle the imperialist forces that contribute to the oppression of racialized and colonized peoples globally. The editors of this collection are under no misapprehension that decolonization can occur by way of metaphor.4 Nonetheless, what the model of familiarity does is encourage us to deepen our relationships with each other.

Returning to the work of Mohammed el-Kurd, he asks what the solidarity cry of "We are all Palestinians" truly means. For him, it means "all of us–Palestinian or otherwise–must embody the Palestinian condition, the condition of resistance and refusal, in the lives we lead and the company we keep." For him, this means taking on greater sacrifices for the cause, which encompasses acts ranging from quitting a job to self-immolation, as well as the "thousands of things in between."

The extra step of familiarization through attending a community reading and hearing firsthand from the translators of a work is not a "sacrifice" in the way that el-Kurd is talking about. It doesn't "crush the doer" in the way quitting a job might. But it certainly asks something of us that we might not otherwise give. What I think el-Kurd captures beautifully is that personal sacrifice might not always disrupt the status quo, but our key concern should not be their status quo–it should be ours.

Might embracing familiarity, as trace press' reading experiences invite us to do, help us resist and refuse the passivity that the "humanization" trap lulls us into? How might an openness to such reading experiences push us towards richer and more engaged solidarity in other aspects of our lives? Poetry, and especially poetry in translation, encourages us to become at home in uncertainty, to lean into multiplicities. The poems in Arabic, between Love and War playfully engage the impossibility of language in all sorts of contexts. Might trace press' reading experiences further help us cultivate creative sensibilities that are daring and unafraid of contradiction, the kinds of sensibilities that open us up to one another in new and provocative ways?