Shahana Rajani, Four Acts of Recovery (2025), film still. Courtesy of the artist.

I recently met Shahana Rajani through various friends who had been trying to connect us after her relocation to Toronto from Karachi, Pakistan. Rajani is an artist whose practice stems from collaboration, pedagogy, and activism, and centres issues of climate justice within the local context of Karachi. Her collective Karachi LaJamia recently won the 2025 “Asia Arts Game Changer Award.” Rajani and her collaborator Zahra Malkani originally started their collective in response to censorship in the arts in Karachi, after a few violent attacks against artists and cultural workers who were speaking up for Indigenous rights. The duo felt that the community was generally complying with this call to silence, and out of frustration decided to create an alternate pedagogical experiment to share the history of activism in the Karachi art community.

What began as a series of workshops became a long-sustained collaboration rooted in land, placement, and belonging, and the collective work has also bled into Rajani’s solo practice. Her recent film and installation work, Four Acts of Recovery (2025) looks at the River Delta and fisherfolk communities who have moved with the river for generations. Recent exhibitions of this work have been at the National Museum of Qatar, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp Belgium, and MOT Museum of Art in Tokyo. Upcoming solo exhibitions will be held at Parasite in Hong Kong, at Nottingham Contemporary in the UK.

We spoke about the translation of the terms Indigenous, settler, and refugee in Urdu and in a Pakistani context—a country that was formed from the division of maps after partition in 1947, when millions of people were uprooted from their homelands and in the same breath, displaced those who were there before. I often think about how the nuance of diasporic identities can become flattened when one moves to Turtle island, as we are trying to unpack the dominant culture’s power over the Indigenous people here. But Rajani speaks about how the decolonial struggle in North America is also an inspiration for those in South Asia and around the world. I asked Rajani about how she navigates these relationships in Karachi, a city mostly made of refugees from various conflicts over the last seventy years. As we discussed her practice, Rajani raised a particularly poignant question that she asks herself: “What are the ethics of inhabitation?” She explained how ties to the land are not necessarily associated with a specific place—as some of the communities she works with have always been nomadic—but that sometimes the relation comes back to graves, or where your ancestors have been buried.

The older I get, and the longer I witness violence around me, the more important beauty—and making space for witnessing beauty—feels.

Could you tell me a little bit about how you became an artist?

I had a circuitous route into art-making. The first few years of my professional life, I was bouncing between visual arts, art history, and curatorial studies. Then, once I moved back to Karachi after completing grad school at University of British Columbia in Critical and Curatorial Studies, I became part of this artist collective called the Tentative Collective. It was founded by artist Yaminay Chaudhry, and she had just finished this brilliant project called Mera Karachi Mobile Cinema that was experimenting with collaborative and community-based filmmaking. In 2015, we programmed a series of screenings and interventions in public spaces using a rickshaw-powered projector. The experience of situating ourselves in the city and witnessing art as a living, breathing thing that unfolds across urban space and does not belong to the gallery; and the experience of working with and learning from communities, spending time with audiences who are not traditionally considered art audiences—these early experiences radically changed my understanding and imagination of what an art practice could be.

That leads me to the next question. When did land, state, and climate justice start to become central themes in your work?

They’ve been in my work from the beginning. One way to tell the story of how I arrived at these concerns, is that around the time that I shifted back to Karachi in 2013, Karachi was under a lot of media spotlight. Central to the post 9-11 “war on terror,” Karachi was being featured in both international and national media as the world's most dangerous city. It was around this time that me and my collaborator Zahra Malkani were alerted to a series of “terror” maps of Karachi being produced and circulated in newspapers. These maps were constantly reducing the city to no-go zones, red zones, and bomb sites. We became interested in thinking about the intentions, workings, and consequences of these maps. It was clear that they were not objectively mapping a city but creating a narrative of the city. Certain neighborhoods, often either Indigenous or refugee neighborhoods and settlements were being labeled terror zones. These maps were preparing for and legitimizing the enforcement of military operations that occurred later and that were allegedly working to secure and create safer spaces in the city. The maps were a key part of this formula. Zahra and I started exploring the nexus of militarization, real-estate development, and representational regimes through our first collaborative project called Exhausted Geographies.

It was that initial interest and realization that opened the path to so many more things. I began exploring the violence of visuality, and its mechanisms of erasure, which have historically accompanied urban development. I spent a year in newspaper archives, researching the histories of displacement and dispossession central to the “making” of Karachi in the 1950s and 60s. I then came to learn about ongoing dispossessions of Indigenous lands and started working with the activist organization Sindh Indigenous Rights Alliance.

From very early on, I was made aware by Indigenous activists like Hafeez Baloch and Faiz Mohammad Gabol that the struggle is not just at the level of land—struggle is also over image, visuality and visual representation. It’s very similar to rhetoric here, where Indigenous lands were considered terra nullius, barren wasteland, or empty deserts.

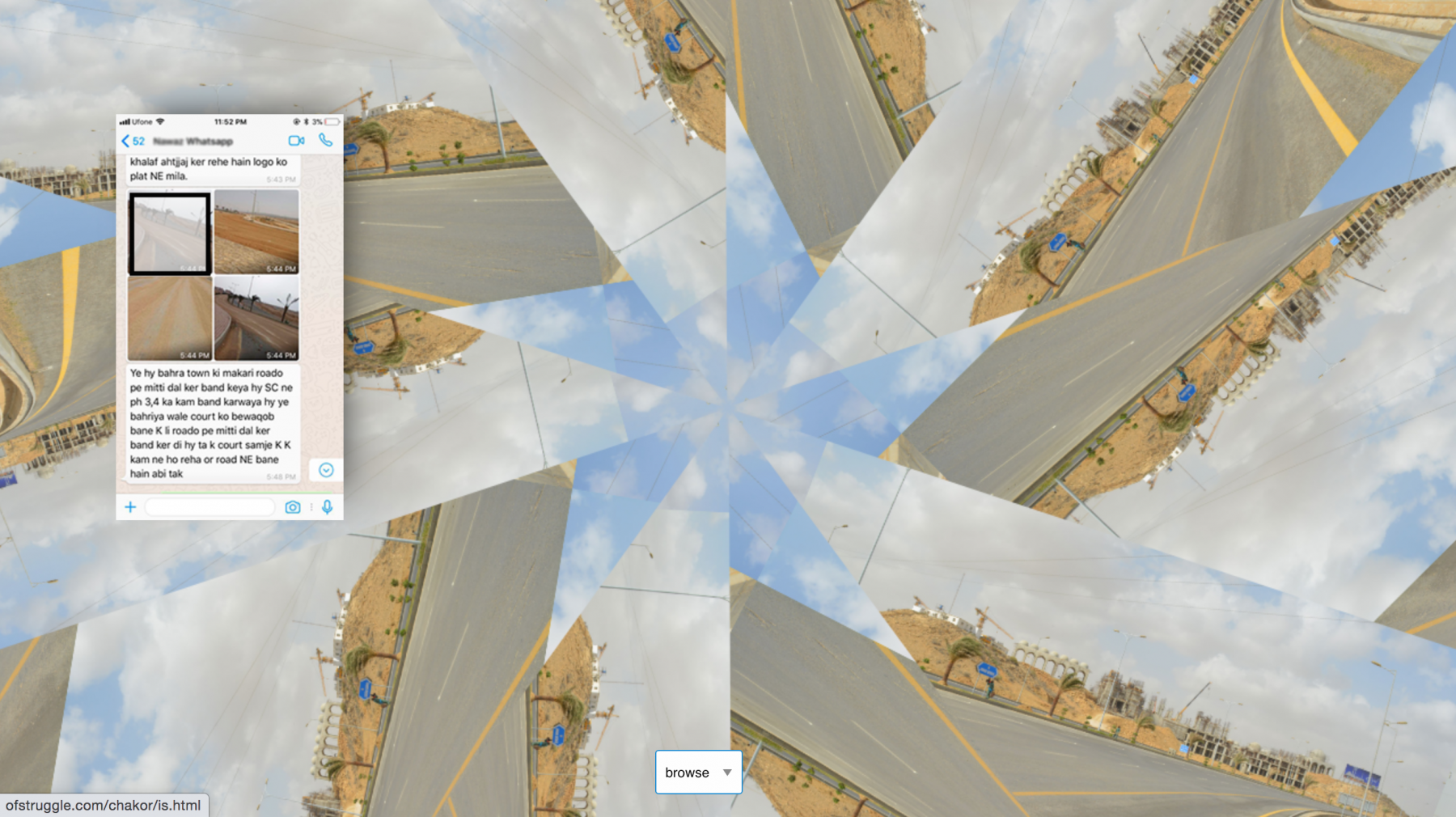

Me and Zahra’s early video work Jinnah Avenue (2017) and our net-art project ofstruggle.com (2018) sought to document and witness these processes as they were unfolding in the neighbourhood of Gadap: where a mega real-estate project was unleashing immense violence. As visual artists, we were reflecting on how to reckon with this visual legacy and with the task of seeing. We were also trying to learn, explore, and experiment with counter-visualities and alternate modes and methods of representing landscapes.

I was also thinking about this visual representation of Karachi in the media post 9-11, but from a completely outside perspective. I haven't heard about the way it was being perceived on the inside—it’s representation both at the local and the international level.

As a diasporic kid, the only visual representation I saw of Karachi at that time was segments like The Vice Guide to Karachi where they literally interviewed a hitman. It’s interesting to think about how the community was reflecting on that representation.

On the one hand, we had all these images of certain neighborhoods as terrorist hotspots and danger zones that needed to be secured. On the other hand, we also had people like Perween Rahman, who were using the maps for radically different purposes. She was an urban planner, activist, and director of the Orangi Pilot Project Research and Training Institute. She was leading a project to map informal settlements, through community-based mappings, to help them get property titles and land rights. Her map was the opposite of the terror map: it was refuting and challenging the idea that the city’s peripheries are empty or insecure. But, she was ultimately killed over this map in 2011 by the land mafia.

It's almost like double colonization, right? I don't know if there was any of that mapping done during British colonial rule. Then, post-partition of India and Pakistan, the Pakistani government started redrawing all the territorial maps. New people started coming in after the partition in 1947, and then again after the multiple wars in Afghanistan and other regions—there is constantly an influx of refugees.

Totally. When the British took over Karachi, Indigenous Sindhi and Baloch communities were forced to go from nomadic, mobile ways of living to being told: “No. Now this is where you live.” Maps were crafted that snatched pastoral lands, and that enforced the boundaries of private property. When the Pakistani state was formed in 1947, Sindhi and Baloch communities had to deal with new maps, new borders, new dispossessions. These communities are familiar with and well versed in the violence of the map.

What drives my own practice and research is not necessarily the goal of making art, but centering pedagogy [...] The artwork often emerges as a byproduct. It is the relationships that are at the center of it, and this desire to learn and share the learning.

One of the biggest questions I have is, how do you reconcile your own place as a settler in Karachi (as so many people are, because of partition) in the community work that you’re doing? Does any of your own journey play into that or show up in the work?

It's a complex question in the sense that the way in which we use the term “settler” in Canada—that word doesn't translate as neatly into Karachi's context. One of the reasons being that the partition of India and formation of Pakistan was predicated on the largest mass exodus of refugees amidst immense violence. But of course, this story of violence and forced migration also rendered invisible the displacements of Indigenous communities that followed.

Partition wasn’t just the cutting up of land, it also resulted in the partitioning of cities from their own histories as the government set out to build a new nation. Karachi for example, was a predominantly Hindu and Sikh city: a city built by Sindhi Hindus in the eighteenth century. Most of whom, after partition, were forced to leave their city.

My grandparents came to Karachi, from a small village in Kathiawar, India. Growing up, I could feel my grandmother's longing for another land that she and I no longer had access to. My own research and practice ultimately comes down to this question of: what are my responsibilities to the city that I have grown up in? What are the ethics of inhabitation?

I have been navigating these questions through my collaborative, pedagogical project Karachi LaJamia with Zahra Malkani. Over the years, we have closely collaborated with Indigenous community and activist organizations fighting to protect land against development, militarization, and resource extraction, and facilitated a series of public courses in the city. We wanted to create a space for learning and community-building outside the increasingly surveilled universities where we were teaching. Across an increasingly bordered and fragmented city, this was our attempt to build solidarity with ongoing struggles in the city, and to resist the ongoing and interconnected enclosures of land, knowledge, and memory.

Something that Zahra and I have also been thinking about is the use of the English term “Indigenous” in the context of Karachi. One of the organizations that I work with is called Karachi Indigenous Rights Alliance. They explained that in 2013, when they founded their initiative, they strategically used the word Indigenous and kept the name in English, even though most of the founding members weren't even familiar with that language. But one of the members pointed out that they needed to use this term so that their struggle translates in an international context.

The term used in the local languages—in Urdu and in Sindhi—is Maqami. Elders explain that maqam can be understood as a site, but also graves. To be Maqami is to belong to the dead, to be connected to the graves, and it is through those graves that you have a connection and history with the land.

But in a place like the Indus Delta, where the sea is submerging homelands, these ways of relating and belonging are also changing. My new film Four Acts of Recovery (2025) traces the practice of painting murals through which displaced fisherfolk communities maintain connection with their disappearing homelands and sacred shrines. It is through painting of graves and shrines, and not the physical graves themselves, that these relationships and connections to land are being maintained and sustained.

That's so fascinating, because we think so much about the land, but this term translates to graves, and where your ancestors are buried. And, in this case, what if that location becomes flooded? Then the memory of where the ancestors are buried becomes the sacred site.

And how new modes and methods of connection are arising as communities are forced to leave their lands. It’s also interesting to think about this in terms of how Indigeneity is conceptualized and understood by Karachi’s Maqami communities. It is an understanding and relationship to land that is not bound or confined to one place, but one that embraces mobility and movement. Mobility has been so inherently a part of life for generations. For pastoral living, you're going where the water takes you: you're shifting to different islands depending on the tides and seasons, the flow of the river, and catch of fish. People were not necessarily rooted in a single fixed place, but shared a rootedness across a vast and cosmopolitan network. As Baloch scholar and poet, Ghulam Rasool Kalmati has explained, in belonging to the grave, to the land, and to the dead, you're not belonging to a bordered specific area, but to vast borderless regions of mobility, trade, pilgrimage, and exchange that have existed long before the modern age.1 I find that beautiful to think about.

Urdu is the national language, and Sindhi is the regional language. What is the Urdu or Sindhi term for refugee or settler? Is there a word for those terms?

For partition migrants it’s muhajir. The vast majority of working-class muhajirs continue to live incredibly precarious lives post-partition. The concept of the “long partition” as discussed by Vazira Zamindar gets us to reckon with the fact that partition is not a one-time event that just happened in 1947, but for many families and marginalized communities the displacement is endless and infinite. And then there are the muhajirs who came with more privilege, who found class and social mobility in new Pakistan. And maybe to that group the settler terminology could be more relevant.

That's what I'm thinking about. I was curious if there is a separate word, because there is the muhajir, but there are also the people who have become landowners and who have formed governments. There is a dominant class of people who at one point were refugees but came with some wealth, or at least were able to purchase property and find wealth and establishment. The same idea translates to the people on Turtle Island. Everybody was an immigrant at some point, unless you're Indigenous, but there are people who have been here for generations and were able to find wealth and resources. There is a difference between their reality and the reality for recent refugees and migrant labourers.

When you're working with these Maqami communities, Indigenous communities, how do you find your collaborators and work with them ethically? Or in a way that feels constructive for everyone involved?

All of my work is very much community-based, collaborative, and emerges from long standing relationships with activists and community organizations.

Four Acts of Recovery emerged from over five years of working with activists and community organizers in fisherfolk settlements of Karachi such as Nawaz Dablo and Fatima Majeed. Through Karachi LaJamia, I had already been working with the Pakistan Fisher Folk Forum. Its members and activists have been fighting for the last four decades to protect the Indus River and Delta, have led incredible anti-dam resistance movements, and have fought off and managed to protect islands near Karachi from being turned into world-class tourist resorts. I turn to these friends and mentors for guidance.

The only reason I felt comfortable making a film was because there was a level of trust, friendship, understanding, and collaboration that we had developed with each other. I also knew that I wanted the making of the film to come from conversations with the painters and with the Dablo family who are featured in the film. We came up with a lot of the ideas together—about how the filming should be done, or what the scenes were that needed to be staged. But coming back to your question, I would say that for me the question about how to ethically make work in a time where field work and research can be incredibly extractive, is one that I have spent a long time grappling with. And it’s a question that perhaps we must continue to grapple with.

What drives my own practice and research is not necessarily the goal of making art, but centering pedagogy: to create collective learning environments that center the struggles of communities being erased from the city, to connect with and learn from this incredibly rich and vibrant world of activism against displacement and in defense of Karachi’s ecologies. The artwork often emerges as a byproduct. It is the relationships that are at the center of it, and this desire to learn and share the learning.

You've seen people like Perween Rahman, who you were describing before, literally put their lives at risk for this research. Have you felt any threats or fears about the way you're going about your work? Or do you feel in some way that having the artistic output makes the work less threatening?

That's a good frame. I haven't thought about it like that. But in some ways, yes, having this niche output does make it safer.

Less political, somehow.

Or at least less accessible, or more shrouded or veiled. Those who want to can access it, but to the shadow state and its agencies the veiled languages of political cultural production are harder to follow and understand.

But safety is never guaranteed. One of the reasons that we started Karachi LaJamia as this pedagogical art project was the murder and assassination of Sabeen Mahmud, who ran T2F, The Second Floor, which was a cultural space in Karachi. In April 2015, she hosted a talk where Baloch activists spoke about enforced disappearances. She was killed on the way home from that event. It was a message to all cultural workers: stay away from political issues. The fear, silence, and acquiescence in the weeks that followed made us realize how much the military-state is invested in maintaining art and culture as depoliticized and disconnected from political struggles in the city. Who and where is our community? How can we continue to fight for our freedoms against state repression? How can we collectively re-politicize art education and practice? It was these questions that led to us founding Karachi LaJamia that summer.

We wanted to do a summer course in public spaces of the city and have students learn histories of art and politics that aren't taught in higher education systems. That was the first course we taught and we thought it would just be a one-off thing, but we enjoyed it so much and it felt so meaningful, that then it became a series of workshops that we kept doing.

I also read your texts Wild Thoughts: Land and Knowledge Enclosures in Karachi and The Militarised University and the Everywhere War (2018) which gave me a bit of insight into this. I loved the text about the university in particular, because even here, I feel like the university used to be the site for political and difficult discourse, but more and more people shy away from that or don’t want to politicize the classroom. With Karachi LaJamia, did the collective start as pedagogy and move towards making artwork from there?

It was about learning together. We saw how securitized and disconnected schooling had become from the communities, land, and ecologies of the city. Karachi LaJamia started as our way of moving outside the walls of institutions, to situate art practice and pedagogy in the larger urban context and its concomitant struggles. Each course we organized was site-specific, always in collaboration and conversation with ongoing movements and struggles to defend the city’s ecologies. It was much later that the research led us to making artwork. I think that came about because we felt invested in bringing the knowledge we were learning through our collaborations back into art, institutions, and exhibition spaces, and working towards transforming them.

Shahana Rajani, Zahra Malkani and Abeera Kamran, ofstruggle, 2018.

A public course organized by Karachi LaJamia, 2022.

Shahana Rajani, Four Acts of Recovery, 2025, film still.

How does the collective work then flow into your individual practice?

Karachi LaJamia is something that we've been doing for over a decade now and it’s informed every part of who I am. Without the joy and friendship of collaboration, I don't know if I would be an artist at all. In my individual practice, I'm working with moving image these days. But Zahra and I always see so much of a reflection of each other in our individual practices. We love to challenge and break apart these modern ideas of individuality, authorship, and ownership. When one deeply collaborates with another, even ideas and ways of thinking become intertwined. It's a beautiful process to make in the company of another.

My collaborations and friendships with activists such as Hafeez Baloch and Fatima Majeed also deeply inform my own practice. They have taught me that knowledge is always meant to be produced and shared in and with community, and I seek to extend the same spirit of care and generosity in my work. It has also allowed me to learn the lineages and ethics of representational work—to center this idea that you make, draw, film, and represent to connect and be in relation to the land and each other.

You recently won 2025 Asia Arts Game Changer Awards India for Karachi LaJamia. I understand that due to the political tension between India and Pakistan, you could not accept the award in India and went to Sri Lanka in order to do so. How have you been able to cross those borders, or political divides in your artwork?

In the first five or six years of Karachi LaJamia the practice was hyperlocal, situated in Karachi for people of Karachi. As we built this larger research archive and developed our own art practice, it meant that the works could then travel across borders even when we could not. It opened up different possibilities and audiences for our work. We've had the privilege to show at Khoj Studios in Delhi, and then at Colomboscope in Colombo, and in both those situations we have been so struck by how strongly the work resonates across South Asia. The borders just mean that it's not possible to travel to India. Yet, our work has been shown, and people reach out to us after going to an exhibition and are sharing the ways in which it connects to urban struggles in Delhi or Mumbai or elsewhere. The same in Colombo—just how much the questions and processes of militarization and development have been so similar to what we are experiencing in Karachi. These encounters and exchanges have been really meaningful, helping us realize the shared nature of our struggles and all the possibilities that that opens up.

How do you find the conversations about sovereignty and rights to land compare between Canada and Pakistan?

There are a lot of connections, but also a lot of differences. For instance, when I came to grad school at UBC over a decade ago, I still remember the first time I heard the land acknowledgement and being moved by it—and just thinking on a daily, micro level, what are the ways to center and acknowledge Indigenous claims? I saw a lot of that work being done within academia and in Canada. Those things, in some ways, felt aspirational. Maybe even unconsciously, it informed so much of the work that I went on to do in Karachi. But one thing that I'm forever learning is that there is so much to learn across difference, and that the struggles on Turtle Island have informed so much of Indigenous struggle around and the world in South Asia and in Pakistan specifically.

Oh, that's powerful. I'm often thinking about my relationship to place. It’s very refreshing to hear about all of the complexity, because sometimes in Canada we forget about that. We're thinking about the struggles of people here, but we're not thinking about it much in other regions. Even considering how the vocabulary is helping form or articulate struggles abroad helps the conversation feel more global.

I feel like it’s your world opening in a different way—and it feels good. I haven’t had much opportunity to show work here yet, but one of the few things I have done is a workshop at Mercer Union as part of their session series. It was the first public facing thing that I was doing in Toronto, and I was presenting on the sacred geographies of the Indus Delta, thinking about the politics and ethics of representing and filming these spaces and what it means to unveil these spaces for a global audience. I was worried whether people would connect with research so rooted in Pakistan. Then, when the workshop happened, it was such a beautiful experience to see all sorts of different people turning up, and the ease with which people were able to resonate with some of the issues. It reminded me of all the ways in which work is always translating and crossing over and just surprising you in so many ways. I feel like those are the things that I'm learning and noticing the more I'm living here: the openness, the generative curiosities and exchanges that are possible in this city.

It's true, people want to learn, and there is a lot of crossover between struggle and research. Your new project, Four Acts of Recovery is showing internationally at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo and in Antwerp at the Museum of Contemporary Art. There is a film, installation components, and some paintings by some of your collaborators.

One question that came up is related to maybe, the digestibility of politics in art: Where does beauty become necessary in processing some of the violence and erasure in your work?

Oh my god! I'm so glad that we didn't forget this question because it made me smile when I read it. The older I get, and the longer I witness violence around me, the more important beauty—and making space for witnessing beauty—feels. This is something that the fisherfolk community and painters of the Indus Delta have also cultivated in me.

I remember first coming across these murals in fisherfolk settlements, where people are not only displaced from their lands, but their lands no longer exist, submerged under sea. There's an immense brutality to that experience and loss, and as you're walking through their neighborhoods, you're seeing these beautiful mural paintings everywhere. Some paintings are of water shrines, some of boats at sea. Some are paintings of fish and aquatic life. The murals felt like they were making space for, or, reminding its inhabitants of the worlds of abundance and beauty that continue to exist amidst annihilation and catastrophe. This is something that really struck me about this community’s painting practice, and I felt like I wanted to make this film to center that practice and possibility. There are beautiful, soft, tender practices of painting that are keeping endangered worlds alive and present.

A few years ago—maybe also around the time that I was thinking of moving countries—I was feeling weighed down by all the darkness. Witnessing so much violence unfold but also seeing friends and communities being targeted and arrested and killed and disappeared, I was feeling really cynical and hopeless, especially about the task of making art. But spending time in fisherfolk settlements of Karachi, the painters and patrons of these murals showed me the centrality and power of visual expression. For communities at the frontlines of climate catastrophe, art-making is at the heart of life and survival.

These are not new practices, but part of older Islamic traditions where to contemplate beauty is to contemplate God, and to contemplate God's creation. Mystic seekers spent their whole lives cultivating their senses and spirits to beckon, witness, and connect with the divine through the boundaries of form. So, these are not just secular landscape paintings but provide spiritual orientations. To paint the sea becomes a sacred practice of zikr/remembrance.

That's so lovely. I love that idea, that to contemplate beauty is to contemplate God. We need to find moments of respite among the chaos.

There's this part of the research for the film where I went to meet a community healer, Fatima bibi. She draws and makes talismans for healing. She's also a Quran teacher and educator. I wanted to connect these mural landscape paintings to this sacred art of drawing talismans—where to draw something means to protect it. I was thinking about how these paintings were being activated as talismans.

I asked Fatima bibi, “Where does this knowledge come from?” She was like, “Oh, it's been in my family for seven generations.” I asked her where her ancestors might have gotten this knowledge from. She told me this amazing story, that I cannot get out of my head, and has made me think of art-making in such a different light. She said that this knowledge descends from Adam, the first prophet. When God threw Adam and Hava (Eve) from heaven onto earth, he separated them and placed them on different corners of the earth. Adam was upset and dejected because he had lost God, and he also lost Hava.

Fatima bibi kept making jokes as she told me the story. She said Adam just sat and cried by the river every single day. Then one day, finally, God took pity on him and he sent Angel Jibrail to go help Adam. Jibrail appeared on the sand dune where Adam was sitting, and said: “I'm here with a gift from God and a remedy for your situation.” The gift was of Ilm ul-Raml, which in Arabic would translate to “knowledge of the sand.” But she explained it as the knowledge of the dot and the line.

Jibrail put four fingers on the sand dune, making four dots, and then he told Adam to do the same. So, Adam made four dots with his fingers, and then Angel Jibrail drew four dashes between the dots, and told Adam: “All you need to do to find the answers that you seek is to meditate on these forms. The nukta holds within it answers to all the mysteries in the universe.” He said: “Remember that the drawing of the dot and the line is a mystical practice, and it's going to lead you back to your beloved.” Adam spent a long time looking at the dots and dashes that appeared in nature around him. It's by meditating on these forms that he apprehends and understands the cosmos, and comes to understand the ninety-nine names of Allah, and finds and reunites with Bibi Hava.

If you then think about it. This divine gift of drawing given to Adam is literally a way for him to navigate loss and separation. What if we were to imagine the history and lineage of visual representation through this encounter? Drawing, then, becomes a way of helping us navigate a world in which we are always experiencing loss and separation; grief and violence; allowing us access to lost, hidden, worlds; enabling us to return.

I don't think I can ask any more questions now. That is so moving. No notes.