A journal for storytelling, arguments, and discovery through tangential conversations.

Thursday, September 4, 2025

|

Ada Kalu

Rarely is the camera used to protect. More often it serves to capture, expose, and surveil. Deborah-Joyce Holman’s Close-Up stands in defiance of this, offering an alternative to this use of the lens. Unburdened by distraction, the film is a quiet loop of carefully framed shots following actress Tia Bannon around an apartment. We focus solely on her face, shadowing the mundanity of her actions—filling a kettle, eating fruit, lying down—entranced by her preoccupation. There is no grand narrative, no sound beyond her movements, and yet, we are left wanting more. What is she doing? What happens next? The slow pacing and tight framing bear the weight of expectation. Surely, such close contact must satisfy our curiosity and bend to the whims of our desires. But even her absence—a two-minute window—is controlled. Waiting like expectant guests, we are left looking around. Presented with an opportunity to learn more about Bannon, her disappearance triggers the camera to shield once again, viewing her space through paced and lingering shots. These are the set terms for access. This deliberate refusal to accommodate or offer clarity is central to Holman’s practice. Close-Up refuses to placate, instead offering a tension and a kind of aliveness rooted in intimacy and resistance.

Friday, April 4, 2025

|

Ada Kalu

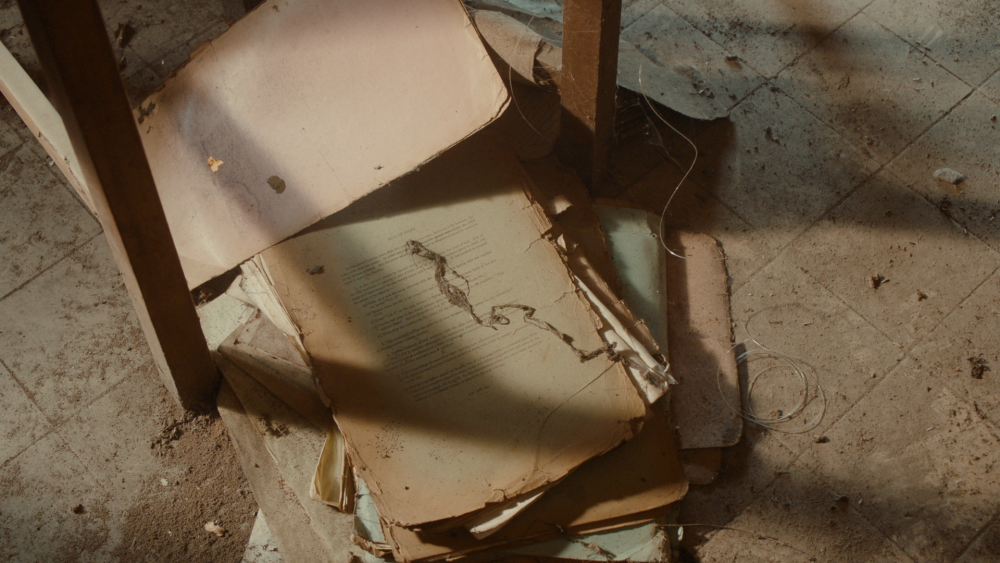

Photographs are a small act of sentimental preservation. Photo albums, scrapbooks, and videos are sites of revisitation and display, and as such contribute to the legacy of the museum as a cultural archive. As an institution, the museum has always been a conservative stronghold—a constant from its privatized roots to its marked transition to a public locale. A portrait of preservation, its artefacts are protected by extensive security measures and object handling rules that safeguard these relics of history. But the rules of safeguarding have changed, and the evolution of archiving means connecting with history in an advanced technological era. So what does this mean for our relationship with the past?

In 2023, Press Gazette recorded a loss of 8,000 journalism jobs across the UK and North America, spotlighting the growing graveyard of media careers. Between 2016 and 2022, a string of articles started appearing on news platforms across Nigeria, questioning the shrinking presence of newspaper vendors in the country. Surmised more recently in a Reuters Institute study, the answer lies in the high cost, low reward rationale of traditional print media. Publications are incentivized to digitally circulate their content due to a growing online audience. The bundling of news publications through subscription-based services means getting more money for your buck.