Photo by Cristina Marx. Sourced via.

My first introduction to Angel Bat Dawid came from a simple Google search: “Black woman clarinetist” when I was trying to find repertoire from underrepresented composers to program on my undergraduate senior clarinet recital a few years ago. Oftentimes, classical music recitals consist of mostly White, cisgendered men from Europe with the occasional woman's composition featured; therefore, I was well accustomed to unsuccessful Google searches of the apparent mythical Black woman clarinetist. One lucky search led me to the music of Dawid, or the genre she names “great Black music”. Before Dawid’s ascension to performer status, her life was informed by the religious nature of her parent’s missionary work as practiced in Kenya and America. A deeper dive into Dawid’s biography and interviews led me to understand that her story as a musician seemed to originate from her early bicontinental lifestyle and familial histories just as much as it developed from playing scales in band class.

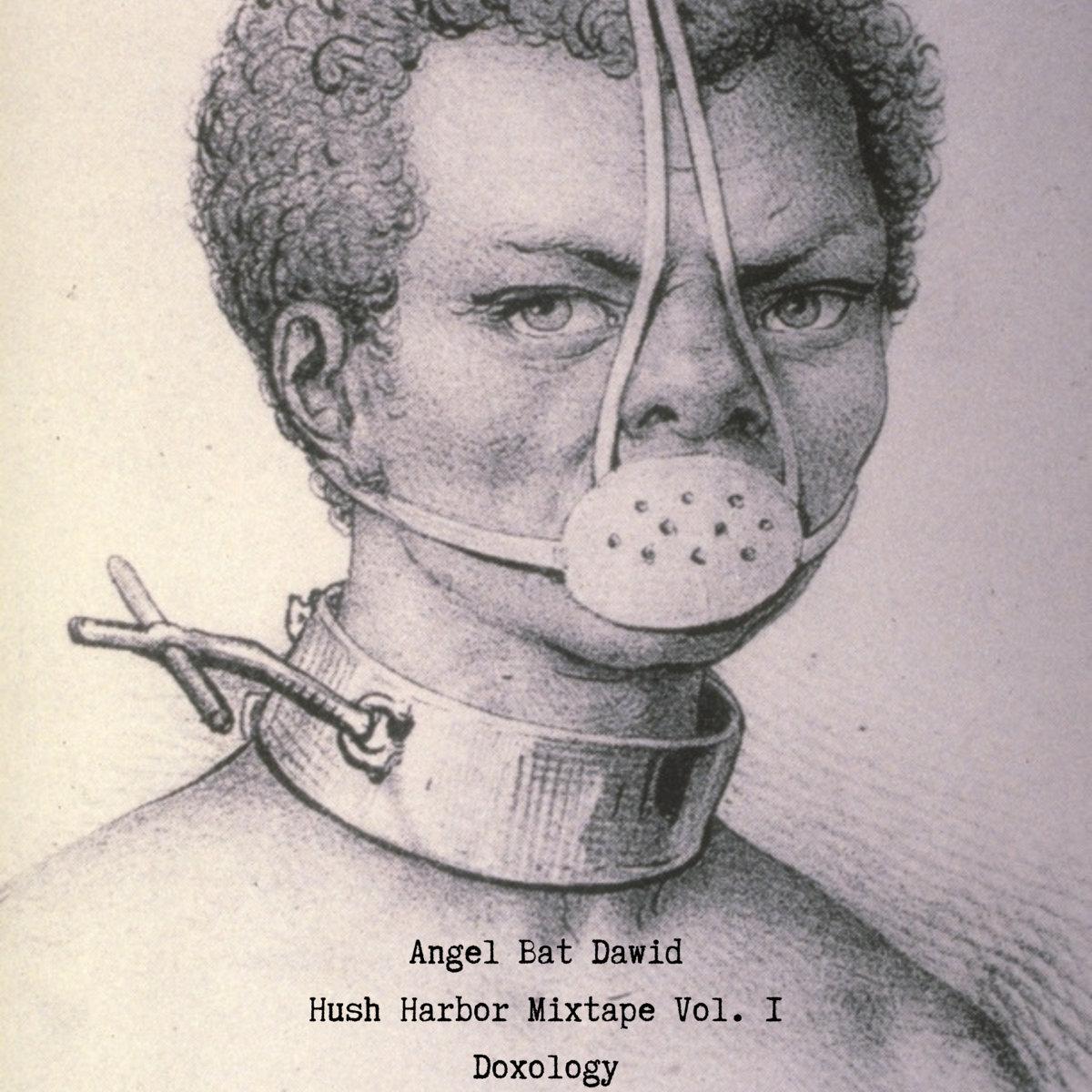

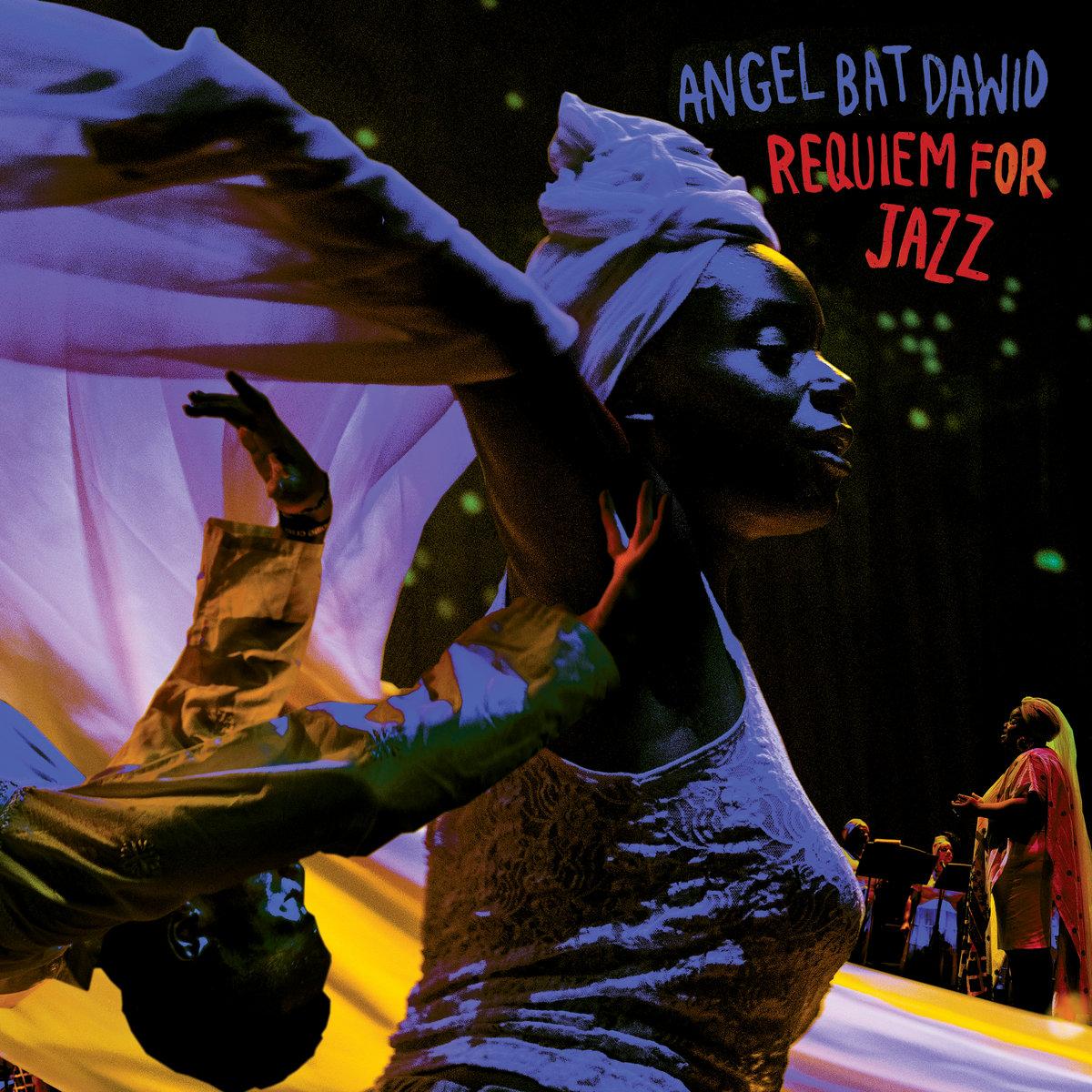

The trilogy of her albums The Oracle (2019), Angel Bat Dawid / Tha Brothahood, LIVE (2020) and Hush Harbor Mixtape No. 1: Doxology (2021) solidify the talent of her impressive aptitude for writing entrancing compositions. The multi-dimensional, multi-instrumentalist Dawid injects elements of ancestral storytelling, improvisation, chanting, and spirituality into her music performance and compositions. Sitting at the intersection of Blackness, music, spirituality, and community, I recognize that Dawid is not an anomaly in her work, rather she is a figure we ought to give flowers to now while her work is being done to reclaim Black music. In conversation, I wanted to explore the ways in which music may have been weaponized against Dawid as well as how she plans to reclaim that power for music that is inherently Black.

Dawid’s deep passion to give back educational tools to Black creative pupils weighs heavy throughout our conversation because of the mutual experiences both Dawid and I share generationally within the anti-Black, patriarchal music industry structures. Dawid does not shy away from verbally reminding others of her intentions to nurture and help foster musical excellence out of the generations that follow behind her. I could not help but think that our conversation is a written record of community building within the field of music that rarely gets taught to young Black musicians in academic settings. Dawid also sets her sights on demolishing White institutional obstacles standing in the way of anti-Black liberation and her choice of weapon is as she says, “Black sonic technologies”. Some may know one example of these technologies as the blues, but Dawid’s work develops upon the historical Black music ground-work put into motion by artists such as Alice Coltrane, Sun Ra, and her Chicago music community. Arming herself with instruments, community, and Black cultural-music teachings, Dawid offers an alternative means of navigating your own destiny within the confines of oppressive White-supremacist music spaces.

They want to put ‘jazz’ on their festivals but have no Black artists. This is why the jam session is so important. It's abolition work as well because the White led jam sessions, they try to tell you their rules but they can’t tell me how to play my music.

You’ve been called ‘wild woman’ (“Great show, wild woman.”) at a show, experienced backlash about your jam session styles, and I’m sure other racial microaggressions as a Black performer. Can you describe the climate of your performances with audiences composed of people who display this kind of anti-Blackness?

It is infuriating and I hate it. Performing in front of White audiences right now is not safe or sustainable for Black musicians. I have experienced racism, misogyny, and assault with the police while performing in Europe. They want to put 'jazz' on their festivals but have no Black artists. This is why the jam session is so important. It's abolition work as well because the White-led jam sessions, they try to tell you their rules but they can’t tell me how to play my music. If you are playing something in relation to music called jazz, then the Black people in the room have authority and I am not here to convince them of that.

The Oracle 2019 album cover. Family photo. Listen here. Sourced via.

As a Black individual with a classical music background, what is the relationship between your physiological presentation (Black hair, garments, the Black body) versus the sonic qualities of your instruments and their vocal timbre tendencies? I know from my classical background that clarinetists and anyone involved in symphonic ensembles are supposed to have a certain sound (implied) and it’s certainly not derivative of any Black aesthetics. I am wondering how you inhabit that space.

We [Black women] are some of the most passionate, dedicated, and practiced. People don’t know what we put in to look like ourselves and sound like ourselves.

You speak about being a performer of “Great Black Music”. I remember being told in all my school education in some way or another that there is no such thing. I remember being denied that identity and ownership.

That’s so racist isn’t it? Black culture is lucrative. America’s music is Black music, it makes billions of dollars and then you look at who makes it. That’s why we are upset because things have never added up. I’m telling this to every Black artist I know just so you know where you fit in. I don’t navigate that tension anymore.

I don’t participate in the White supremacy mythology that we live in because I don’t believe in their superiority. Their myths are everywhere. My myths are what I want to see, which is a Black portal, Black sonic technologies to create that world.

There came a point when I decided to not participate in their structures anymore. I am going to do me whether you like it or not. I accept everything that comes out of my horn because it is about acceptance. I learned much of this from Chicago in the free jazz scene but, I was allowed to be free because of my disciplined background in classical studies.

When you first picked out the clarinet as your instrument, what did you set out to accomplish as a young musician?

I’ve always loved music ever since I was a child. When I used to listen to a symphony or the music to the movie Amadeus, I realized that I could hear all the parts. I thought everybody could do that! You didn’t hear that?! So that’s always how I listened to music. Children are composing in their heads. After ‘formal training’ (piano lessons first and then clarinet), I began to question my original ‘thing’ with music. The people at school made me feel like hearing all the parts was wrong so I was then put into a box but here’s the thing, I’m one of those people who likes to excel at whatever it is I’m doing. I was really good, excelling in their box but there is also this secret bondage that you have making you feel like you’re never good enough because it’s competitive. By the time I was a junior in college, I was starting to think as if music wasn’t for me so I just started working. That’s when I met one of my father’s friends, a great guitarist and my mentor. The elder at these jam sessions my dad used to take me to [in Chicago] gave me my first music notation software. I became obsessed, I was watching Puff Daddy’s MTV show Making the Band and I was so interested in the music industry. I started studying hip-hop as composition to find out what are the elements of a hip-hop beat. I’m using Western notation notating Nas’s words until I realized that I’m a composer. I really love the art of composition and that’s what it’s always been for me.

Angel Bat Dawid & Tha Brothahood 2020 album cover. Cover art by Raimund Wong. Listen here. Sourced via.

How did you transition into a communal musical practice? I know that your family history is relative to Black church music, but I would like to know more about the transitional work it took to move away from your classical background.

It was a very lonely journey for the first 25 years because I didn’t have a tribe or anyone to relate to. The 'free music' community that popped up in Chicago—I love that word free. That word means liberation for Black people and they [free music musicians] call it liberation music. I’ve always loved Sun Ra and being ‘weird’ so I was always othered. That space opened up to various sonic communities in Chicago where David Boykin had a free jazz jam session called Sonic Healing Ministries. At these sessions, I was in an environment that was nurturing towards me being myself even though we were all intimidated to go onstage for a solo. Some of the musicians that I met there began jamming with me at my home, and together we cultivated this environment inspired by the work of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. Some of the musicians I met in those days who I continue to perform with today, we still do not forsake the jam sessions. I don’t always want to rehearse; for me, jamming is sustainable work.

One of the things I value perhaps most about you is that you dream of communal music practices becoming the normal mode of producing music. I read in a Pitchfork interview where you stated,

“One of my dreams is to perform in front of 10,000 people, not for my own shit, but because I really want to hear what 10,000 voices sounds like singing together. To get back to how our ancient ancestors used music as part of our community. It’s actually a very Black thing: we had work songs, we had cooking songs. Music was just a part of life. It wasn’t a whole, ‘let me get on a label, let me make a record’…”

How do we create more of these experiences in a capitalist society, when musicians need to make a living? Is this a dream that can only be achieved with economic-political-social liberation?

I would like to propose this equation: Black business minus White business equals success for Black people. I am separating from them intentionally and that’s hurting some of their feelings. This is rejection, not hate. I’m trying to build something separate from them and intentionally doing it for Black people even if it means doing this kind of business in my head. You may find yourself in a position where you are maneuvering and negotiating the space that you’re in as a Black artist while you are in White institutions. Any time I am in their infrastructure, that is not an ‘I’ve made it’ moment, I am just in their infrastructure. The idea is to always be destructive towards their initiative because we need more spaces where White people are not involved. All of their art museums and universities will be destroyed. I say that with love in my heart. Education is sustainable for Black artists. I don’t mean you have to become a professor; I am starting with my hashtag #AngelBatDawidSchoolofMusic.

What curriculum of pedagogy, practice, and/or philosophy do you envision your future music school to have for itself?

I want my students to learn how to be themselves. I learned to be just me, nobody can make music sound the way I do. What I am learning as I am researching and developing a music pedagogy for young Black creatives, is that it starts with supporting a sense of individuality. In my classes with my students I try to realize early on the gifts that my students have. Everything opened up for one of my eleven-year old students once I gave him the space to compose his own music based on the pentatonic scales. Now I’m just here to guide him to be more of himself, an amazing composer. He never thinks music is hard because I never taught him that it is. I think about myself because it was really my own desire which helped further my interest in music, not so much the music lessons. I’m always researching, studying, and practicing and learning on my own so for the children, it is about keeping that initial spark. That is a level of care that is never given to Black children. What usually happens with training Black children is a lot of violent discipline.

When you’re introducing young pupils to a variety of Black music composers of varying socio-political ethics like Young Thug or Ramsey Lewis, what kind of work are you establishing or building upon for the following generations?

One time when I had a band performance with some students an announcer introduced me as an avant-garde jazz musician who played music that might be different then what the kids knew. I had to correct her by saying that I play great Black music as I asked the kids if they knew what that was. I explained it as, “If you are Black, you are great. Whatever music that comes out of you is great Black music”. One of the little girls asked me what avante-garde jazz is and that’s when I told her that there is no such thing as that. The class I was teaching to incarcerated youth made me study the music that they like, trap music. Although a lot of that music talks about a hard lifestyle like being in gangs, misogynistic and can be hard to listen to for those reasons, I had to engage with it because it’s Black music. There is still a power in their art and the media frames these young rappers only as gang members. I showed my students examples of Polish and Japanese trap artists to remind the incarcerated young men that everyone wants to emulate them!

Considering how a sizable portion of your life is dedicated to education and giving back to Black youth, and that both of your parents are educators (among others in your family), I wanted to know about what was passed down to you artistically and otherwise.

Being born and raised in Georgia, my source of research came from Black churches which has led me to go back and research my sound. There would be chills and not a dry eye when you were in those settings around the Spirituals so I knew it was more special than I could understand at the time.

This brings me to your work, Hush Harbor, experiences which you create to emote and give-back what was passed onward to you through music. From my understanding, Hush Harbor theory/practice is a spiritual Black American music service once held by our ancestors. These services extract histories and stories through ancestral Black musical and creative expression once performed by the enslaved. Considering the variety of experiences you have had performing abroad, how does locational history influence the Hush Harbor performance space specifically when collaborating with various artists from different locations?

Black artists have protested our condition already, but just as we are destroying oppressive systems, we have to consider what to build up. In the state of isolation and oppression, a new sound/sonic moment came out in a very site-specific space. Their [enslaved ancestors] sonic services triggered my hypothesis to look at the oppressive conditions of our people now so that Hush Harbor sessions can happen presently. Every one of my shows and albums is a Hush Harbor as I utilize all this great Black music like the blues, jazz, and hip-hop to get new compositions and sounds out of myself. This is a continual research project that cannot be quantified or qualified by a white person.

Hush Harbor Mixtape Vol. I Doxology 2021 album cover. Popular folk image of Brazilian Saint Escrava Anastacia. Listen here. Sourced via.

Keeping true to your mission on top of existing within a Black woman’s body is tiring work I’m sure. What sacrifices (if any) do you think come with the nature of your specific anti-racist music composition, performance, and education?

I sacrifice being understood and having people jump to conclusions about me. It gets hard being steadfast with my resolve because I prefer to be at peace, but all this White supremacy makes me uncomfortable. I’m always talking about consent because I have to when people have tried to touch my equipment inappropriately or disrespected me. I had to ask a sound guy, “Would you touch Yo-Yo Ma’s cello like that?”. It is exhausting to keep putting things on blast because nobody listens to Black women when we feel uncomfortable. I say this and I think about Nina Simone and Aretha Franklin because they were really going through some shit, I can’t imagine what was happening to them.

Speaking of greats, Miles Davis once said, “...Sometimes it takes a long time to sound like yourself.” What is something you do everyday to get closer to yourself and/or your sound?

I rest because especially after the pandemic, I learned to slow down. This is a struggle for Black women and of mine because I like to work, but I realized that by intentionally saving time to rest, I am constantly able to draw from creative material to compose with. My real office is usually in my room by myself, studying, researching, and praying over everything. I must have some interaction with music and have a morning and evening routine everyday. I believe that sometimes we shouldn’t do something if we’re not in the right state of being because we need to put our needs first—listening to our voices in our bodies. To be the kind of person who I am, I have to practice affirmations everyday to affirm what I mean to myself. I be using mythology like Sun Ra who calls himself the ‘Myth Scientist’.

Requiem for Jazz 2023 album cover. Artwork by Damon Locks. Listen here. Sourced via.

How do you sort out your mythology amidst the realities of everyday life?

You take a story and then you mythosize it. I don’t participate in the White supremacy mythology that we live in because I don’t believe in their superiority. Their myths are everywhere. My myths are what I want to see, which is a Black portal, Black sonic technologies to create that world. I believe you have to have a spiritual practice which is why I’m so influenced by our Ancestors, I always bring them up because they are tapping on my shoulder at all times. I’m sitting here orchestrating in my head what 2023 is going to look like, 2035, 2200..I’ve already said in my head I want to live a long time. This work is not something that needs to happen tomorrow. I’ll wait for the supremacists to move on while I am helping my community build.