Paul Stephen Benjamin. Summer Breeze. 2018. Courtesy of Efraín López and the artist.

Photo by Inna Stravinsky.

A descent into darkness both literally and allegorically accompanied Atlanta-based artist Paul Stephen Benjamin’s recent solo exhibition, Black Summer, at Efraín López gallery in New York City1. The nascent gallery’s small and windowless subterranean space appropriately housed the products of Benjamin’s material and cultural research on the manifold meanings of blackness as a color and state of being, which together form the broad, elusive crux of his conceptual practice. Working across media including photography, painting, video, and sculpture, Benjamin’s corpus bridges integral moments of Black history and art history with an operative aesthetics of blackness—the ways in which blackness circulates as an available material, such as commercial black paints, blacklight, or, for instance, the ‘Atlanta Black’ mortar in the corner of his work space that Benjamin gestured towards during a remote studio visit.

For Benjamin, blackness is at once a formalist abstraction and a tangible reality, as his many variations on the color black cut across its abundant manifestations in order to complicate the delineation of traditional categories of experience. Benjamin’s multimedia, installation-based practice often circles around a central question that the artist reiterated throughout our studio visit: “if the color black had a sound, what would it be?” This synaesthetic impulse—this desire to blur the lines between the sonic and the visual, thinking of blackness as operating simultaneously across different cognitive domains—gives rise to Benjamin’s undefinable, and, on principle, undefined oeuvre. His output serves as a perceptual reminder of Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s assertion — put forth in the duo’s collaborative study and influential theorization of the Black radical tradition in The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study — that “[t]he black thing cuts across the regulative, governant force of (the) understanding.”2 Ungovernable, blackness constantly evades capture and, as in the work of Paul Stephen Benjamin, it is a flexible, historico-political improvisation that refuses to be pinned down.

Michelle M. Wright, author of The Physics of Black Art, has argued and evinced that “Blackness is both a historical construct and a phenomenological experience.”3 Walking into Benjamin’s recent exhibition, the multilayered historicity of the two monumental works on view in total darkness was palpable. The space was illuminated only by the two works, one being a blacklight sculpture and the other a pyramidal video installation of stacked CRT monitors whose color-spectrum had been severely limited. Its orderly aggregation of boxy monitors radiated faint blue-grays about the interior of the gallery as the space rang with the looped croonings of Jill Scott.

“Black bodies swinging in the summer breeze …”

Pause. Cut. Start Again.

The lurching tune repeated the same lyric from Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit over and over again—never progressing, getting tired, or moving on. This musical theme was emitted by the modular video sculpture, Summer Breeze. The work consists of a series of tube televisions of various sizes and resolutions. The largest of the work’s central monitors features a looped clip of a young Black girl going unendingly back and forth on a swing set while the smaller framing monitors shine with either an eerie violet luminescence or display performance footage of Strange Fruit as it was famously performed by Billie Holiday in 1959, as well as Jill Scott’s 2015 performance of the same tune. Summer Breeze overlays the evocative artistry of Holiday—as her lyrics mourn and commemorate the history of lynchings and violence against Black bodies writ large—in such a way that the haunted innocence of Black childhood is brought to the fore not didactally but affectively.

...Benjamin’s artistic practice denotes an investment in the boundary between visibility and invisibility, both from a perceptual and a historical perspective. Erasures and absences are conflated, recycled, and variously announced in his work.

Summer Breeze creates a spectral atmosphere of poetic asynchrony. “To swing” taken as a verb with multiple historical connotations and ramifications is what holds the video work’s distinct footage together, but their distinction does not matter. Evincing the power of reiteration and the cyclicality of history, Summer Breeze’s ghostly repetitions—as the child’s swing goes forever back and forth to the tune of Holiday’s plaintive phrase—attests to Benjamin’s commitment to laying bare the persistence and accumulation of the meaning of Blackness across space and time. In a mode adjacent to that of appropriation art and audio-visual collage, Benjamin’s video works often function by recontextualizing iconic soundbites and televised scenes and recombining them into cacophonies of sound and light, as representations of significant moments in Black history come into direct contact and collaboration with each other. Throughout his work, the past, ever-overlaid upon the present, forms a historical discontinuum of incongruous loops and uncanny spirals from which we can never escape.

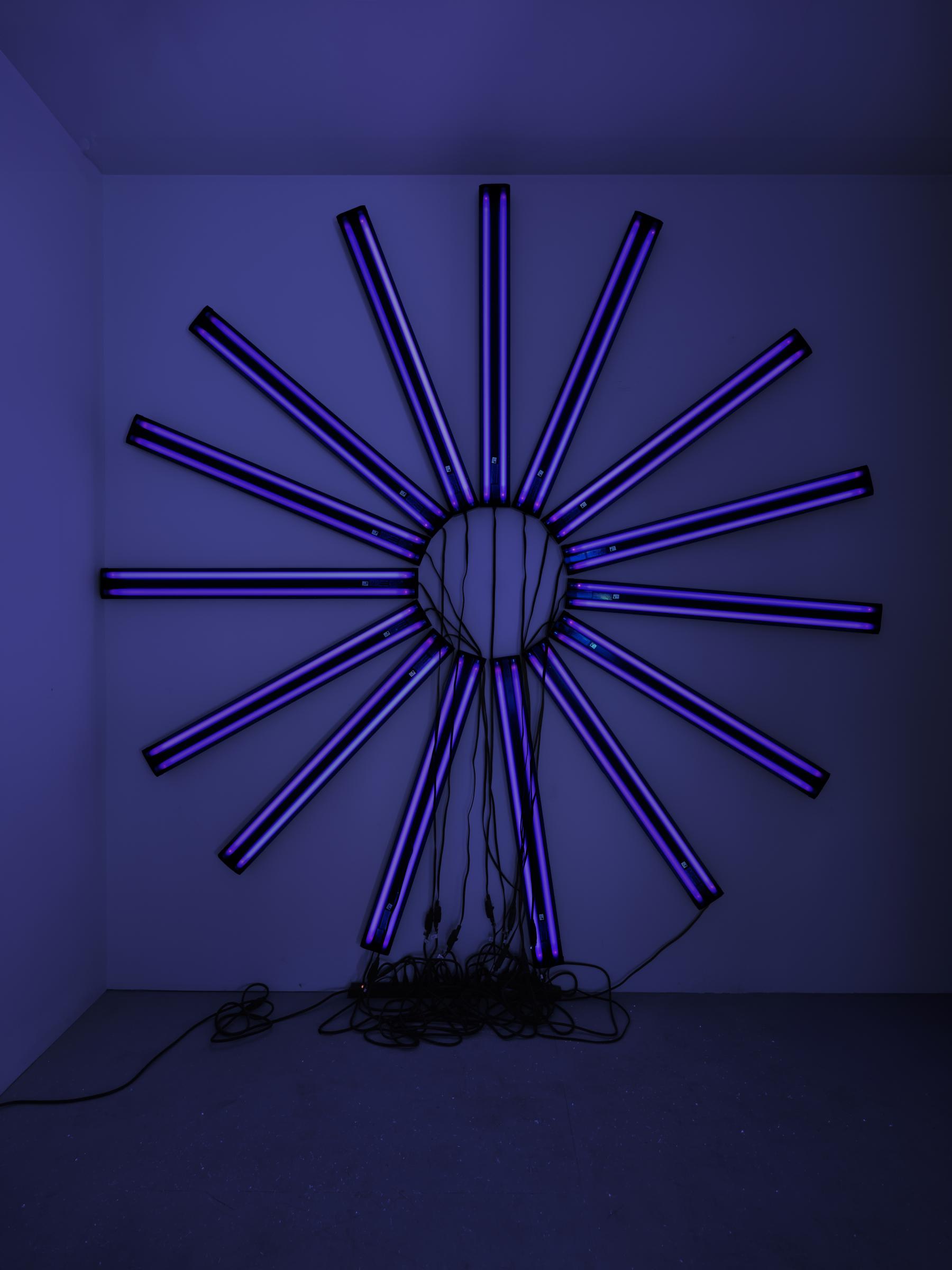

Paul Stephen Benjamin. Black Suns (Ode to Tom Lloyd). 2023. Courtesy of Efraín López and the artist. Photo by Inna Stravinsky.

A notion of inescapability runs through Benjamin’s practice more broadly, as his blacklight installations also lay bare the details and secrets of the viewer, refracting off of their bodily surface and illuminating that which cannot be seen in the light of day. These pieces utilize UV-A light, which emits a fluorescent glow in reactive colors only in the absence of visible light. These works attest to the artist’s multifaceted analysis of the ways in which, as writer and performer Malik Gaines has previously stated, “The power of the surface is inescapable, as is its efficiency as a depository of complex histories.”4 Benjamin’s blacklight installations—of which Black Suns (Ode to Tom Lloyd) was on display at Efraín López—defy preconceived assumptions of blackness and visibility. As I looked around the gallery at my bag, my skin, and my clothes, they shone with a speckled surface luminescence both exposing and alien. Previously invisible stains were suddenly alive—my teeth and the whites of my eyes a disconcerting shade of violet—bearing traces of my recent past that remain invisible to the naked eye.

Black Suns (Ode to Tom Lloyd) followed the laws of scale proposed by Summer Breeze, as both works operated to dwarf the visitor within the space while still being reactive to the intimacy of the gallery’s small underground location. Composed of 48 fluorescent blacklight tubes in the shape of sun beams, Black Suns pays homage to Tom Lloyd, a pioneering Black artist and early adapter of light as a medium during the 1960s. Lloyd’s works, as Benjamin described over the phone, were shown early on in the history of light at the Studio Museum in Harlem, alongside the likes of Dan Flavin, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg. They utilized the tenets of minimalist lighting structures—fluorescent tubes, sensors, and motion cues— that have been, first and foremost, associated with Flavin’s larger-than-life oeuvre. Too often forgotten and wiped from the history of light, Black Suns marks Lloyd’s conspicuous absence from the record as a part of Benjamin’s commitment to “resurrecting his corpus.”5

As with every good discontinuum, blackness, for Benjamin, is that which lives in the gap between past and present; the space between here and there; and the chasm posited between the seen and the unseen.

Taken altogether, Benjamin’s artistic practice denotes an investment in the boundary between visibility and invisibility, both from a perceptual and a historical perspective. Erasures and absences are conflated, recycled, and variously announced in his work. As works of conceptual art, they refract against the idea of what art historian Krista Thompson has described as the function of “shine” in work produced by artists of the African diaspora, by directly subverting the paradigm hypervisibility that Thompson details: rather, Benjamin’s work strategically reverses Thompson’s famous claim. She argues variously throughout her body of scholarship that many artists of the African diaspora use techniques of suffusion and the proliferation of light to blind and bind the viewer to the visual plane. Using case studies such as painter Kehinde Wiley, visual culture propagated by the emergence of music videos, and the popularization of Jamaican dance halls, Thompson sees shine as cultural and artistic technique that “pinpoint[s] the limits of the visible world.”6

But Benjamin takes the horizon of Thompson’s argument to its logical end. Seeking concepts that “pinpoint the limits of the visible world,” one either ends up with the sublime limits of saturation, as in Thompson’s analyses, or with the barely visible, the ghostly, the absent, and the black-lit in the work of Paul Stephen Benjamin. This horizon of experience—the mixed sensation of being seen and yet misrecognized, thereby shaping and redefining the limits of perceptible or acknowledged form—is moreover what Moten and Harney see as binding together the concept of blackness itself. Ever enigmatic,

Blackness operates as the modality of life’s constant escape and takes the form, the held and errant pattern, of flight […] how the soundwaves from this black hole carry flavorful pictures to touch; how the only way to get with them is to sense them […] Knowledge of freedom is (in) the invention of escape, stealing away in the confines, in the form, in the break.7

Another work, not presented at Benjamin’s exhibition at Efraín López but discussed during our studio visit, draws out and further complicates the synaesthetic impulse present within Moten and Harney’s famously fluid description of blackness—this encounter in which imagery escapes the visual to engage with the haptic, an encounter in which “the only way to get with them is to sense them.”

Paul Stephen Benjamin. Ceiling. 2017. Courtesy of Marianne Boesky and the artist.

Taking up a rake within his studio during our video call, Benjamin showed me how Ceiling, a performative installation work of his from 2019, becomes sonically activated by bodily labor. Ceiling consists of a rectangular plot of broken tempered glass arranged in the center of a gallery floor. Often installed alongside the artist’s blacklight sculptures, the glass gives off a signature violet glow—its original transparency turned to pure color, its invisibility alight within the space. Ceiling’s sound is activated by the entry of a person onto the scene, sometimes the artist himself.

Ceiling offers a very different sort of response to Benjamin’s central line of inquiry: “If the color black had a sound what would it be?” The sound of Ceiling is again cyclical and durational, as it is with Summer Breeze, but here it is encapsulated by a sound that reroutes the audience’s sonic expectations by entirely different methods. The sound of raking and walking upon the broken glass are unconventional and yet familiar: its repetitions are even and natural, though inorganic. The sound emitted by the broken glass, under the careful foot of Ceiling’s slow laborer, is a meditative crunch and slightly shattering crackle repeated ad absurdum. The work exposes the slightest movements of its performer. It is a work, like Black Suns, aware of its revealing nature and its material precarity.

Thus, one among Benjamin’s many definitions of sonic blackness is evidenced by each piece of glass crushed underfoot. As the glass falls to pieces over the duration of the performance, Benjamin attests that it is blackness itself that lives in the break. It is, across his practice, at once constant and fleeting, cyclical and new. It is the unnameable thing that crosses lines, forecloses boundaries, reroutes itself and starts again elsewhere. In a way, the dramatic cuts that are constitutive of Benjamin’s looped audio-visual installations speak for themselves. Traversing the fundamentally historical space between now and then, blackness is that which cuts across the gap. As with every good discontinuum, blackness, for Benjamin, is that which lives in the gap between past and present; the space between here and there; and the chasm posited between the seen and the unseen.