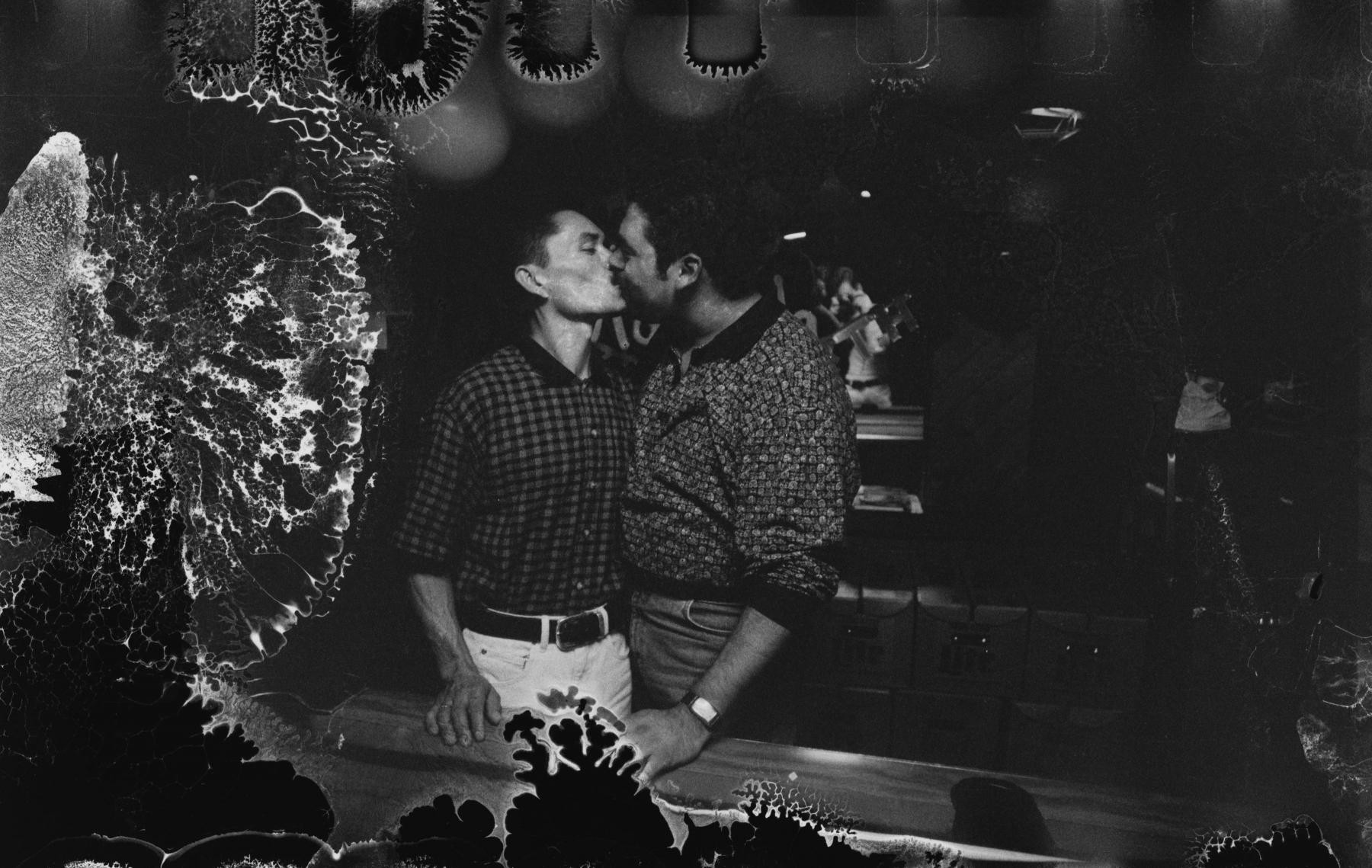

Reynaldo Rivera, Zeneido, Adalberto, Boyle Heights, 2025.

Con miradas siempre nos damos todo el amor

Hablamos sin hablar

Todo es silencio en nuestro andar

Amigos simplemente amigos y nada más

—Ana Gabriel, Simplemente Amigos

In her 1988 song, Simplemente Amigos, Ana Gabriel belts out a confession disguised as restraint. It’s about a love that must exist in the shadows, spoken through a secret code of gestures and glances. The ballad moves between longing and endurance, mapping the tension between desire and secrecy. Similarly, Reynaldo Rivera’s photographs translate the impossibility of public love into forms of tenderness—where desire becomes both memory and a way to exist otherwise.

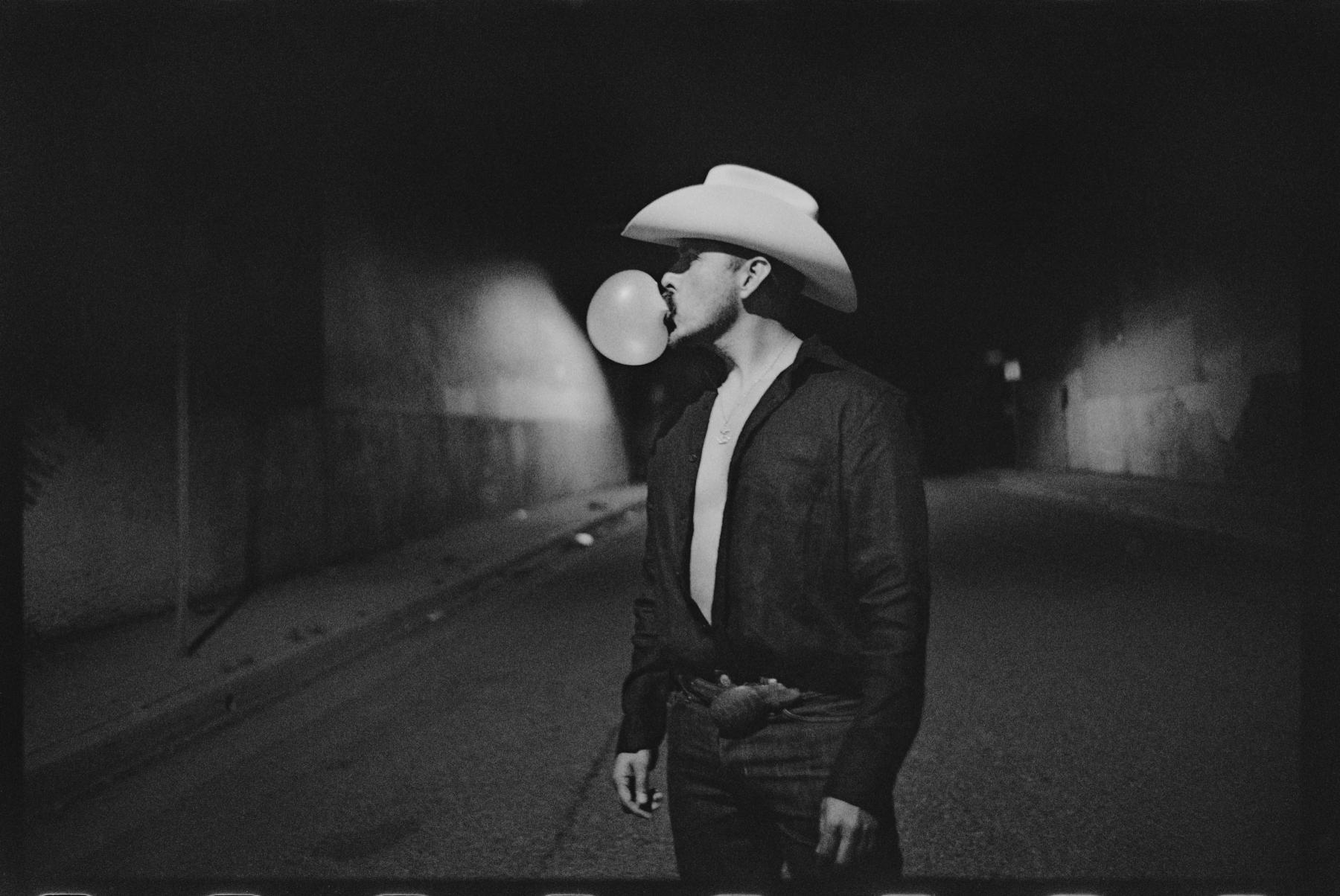

His Los Angeles is not the one full of celebrities, beaches, or Hollywood films that usually comes to mind. Rivera’s images depict a Los Angeles rarely shown. His photographs blur the line between the personal and the political, becoming indispensable records of a world both luminous and precarious. His portraits of performers, friends, and lovers capture a community that built itself through art, nightlife, and kinship at the edges of visibility.

Rivera’s new book, Propiedad Privada, published by Semiotext(e), extends that intimacy and resistance. Combining his photographs with new writing by Abdellah Taïa, Chris Kraus, Constance Debré, and others, the book reveals a body of work that is at once diaristic and political, tender and defiant. It is a testament to a life lived through looking, one that insists on visibility without surrendering complexity.

I spoke with Rivera from his home in Los Angeles. Our conversation moved between memory and philosophy, between laughter and loss, returning always to the question that anchors his work: how to love, and to be seen, in a world that has so often refused both.

It was about giving people what they wanted: to see them as how they wanted to be seen. If someone believed they were a star, then that’s exactly how I photographed them. And, to me, they were stars.

I wanted to start by asking about the new book, Propiedad Privada. The title feels loaded. When I read it—Propiedad Privada, Private Property—I think of ownership, intimacy, maybe even boundaries. How did you land on that phrase?

It's a song by Lucha Reyes, the Peruvian singer (not to be confused with the Mexican singer of the same name). It’s not about real property, it's about the stuff that’s in you: the things that are you, the things you’ll take with you. I feel that we queer folk—maybe not so much young people—but I know a lot of us old farts had to create this inner life that we were rarely able to expose because of fear for our safety. But it was our own, you know? The one thing we owned. It was the one place that we could be ourselves. So the work is about that, about that which is ours—that love between two people—you can’t buy shit like that. You know what I mean? This is not monetary. As a young person, I had a very big fantasy life—and throughout my life, this inner me has been something that I own. That’s mine. That I’ll take with me to my next life.

That’s something I was thinking about in your photographs. When I look at the photographs in Propiedad Privada there is an insistence on beauty no matter where the photos are taken, or whether they’re of people that might not always be recognized, or moments that might usually be kept private. What does beauty mean to you in your practice?

Girl, at the time I wasn’t thinking about it in those terms. I documented my life and the people around it: the people that I cared about, the people that I wanted to preserve and relive. Because that’s really what it was about. It was really a time machine. But by the 90s a lot of these people just were dying off so quickly. Sometimes I wasn’t even able to give them the prints because they were gone.

There’s something about them—it doesn’t matter where they are, what time of day or night—there’s a timelessness to them perhaps because of how you make everyone look so beautiful.

It’s how I view them. If I’m going to take a photo of you it's because I like you. I feel that this comes out in the work. It’s like that with any medium, but especially photography. Look at Diane Arbus for example, her work is just like her. She made everyone look freaky, because she saw the world through that lens. Everything was frightening to her, she chose to photograph those fears, and you can see it in her photos. I photographed the same kind of people but I made them look amazing because that's how I saw them.

Everything you’re looking at in my photographs had something to do with me. And so, you could almost say I’m in the photo. I think the reason why my work might be a little different is because I wasn't making a documentary, I was a part of what was going on. Also photography was expensive, especially when I started. A roll of film used to cost you as much as a burrito. I wish I could’ve taken more photos, but it was prohibitive. Back then we, and I mean, not just Latino folk but poor folk—were usually documented by other people. Where this is something where they’re being documented by themselves, where we’re documenting ourselves.

As far as the photographs in Propiedad Privada, it's very different from the first book [Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City]. The first one was really a gift to Los Angeles, because I always felt that it was criticized for all the wrong reasons. Or, I should say, it was criticized without ever taking us into account: Latino folk here. Whenever people are critical of LA, it is always about the west side. Whenever people talk about Los Angeles, and everyone trying to make it and being fake, superficial, etc—that was never my experience. Most people here didn’t fantasize about being fucking Hollywood starlets. I mean, maybe, of course, one or two here or there, but we didn’t lose sleep over it. These neighborhoods, by the time the book came out, were no longer Latino neighborhoods. I originally thought of the first book in response to what I saw was disappearing out of LA. I’m like, “I need to leave a testament that we were once here.” It was like a living testament that we once lived in Los Angeles—that it was once not just our city, but a city that we thrived in, that all this stuff happened in, all this shit that went right under popular culture’s nose.

It’s funny you bring up the geography of Los Angeles because another thing I really like about this book is a kind of mapping of communities through portraiture. Do you see your photographs as building a geography and history of queer love in LA or queer Latino love in LA?

We have always been put in these fucking categories, and I hoped that with that book that could change. Because we’re all those things, you know? We’ve been involved in so many moments in culture. For example, when you think of punk rock in the US you never think of Latinos. Alicia Armendariz started one of the first punk bands in Los Angeles and in 1976 was opening for the Sex Pistols. But because we weren't good at documenting what we did or put it out there things like this went unnoticed. There is power in photographs, and whoever is in power gets to say what gets included and excluded from history.

This second book, Propiedad Privada, as much as it is about love, it's also about the end of love. I had all these photos of people and all their multiple partners, all their exes. It's funny how people go through life and every time they’re with someone they think “this is going to be forever.” It's also about the way we love and—I know this will sound whacky—but also how we see and love ourselves. I grew up being fetishized by all the men around me, after a while it didn’t even register anymore. This idea that just for being Latino—even as pale as I am—the fact that I’m Mexican put me in this category. I always wondered how much of this we internalize and begin to view the world through that gaze and not our own. What does desire look like to us? This book is about that. Taking our love and putting it out there. In most of the photos of me in the book, I was in love, and I think that’s evident in the photos.

I’m looking at this photo right now, in the book. I wanted to ask you about these photos specifically. It’s Bianco in Silverlake in ‘94, and then on the next page it’s the photo of Amy, you, and Bianco, and you’re photographing it through the mirror. Those are the photos I was thinking about when I was asking about beauty. You know a lot about photography, so you know, portraiture is controversial in its own way. But in these photos there’s this generosity to the people in them.

It’s all love, I mean, this book is really about love.

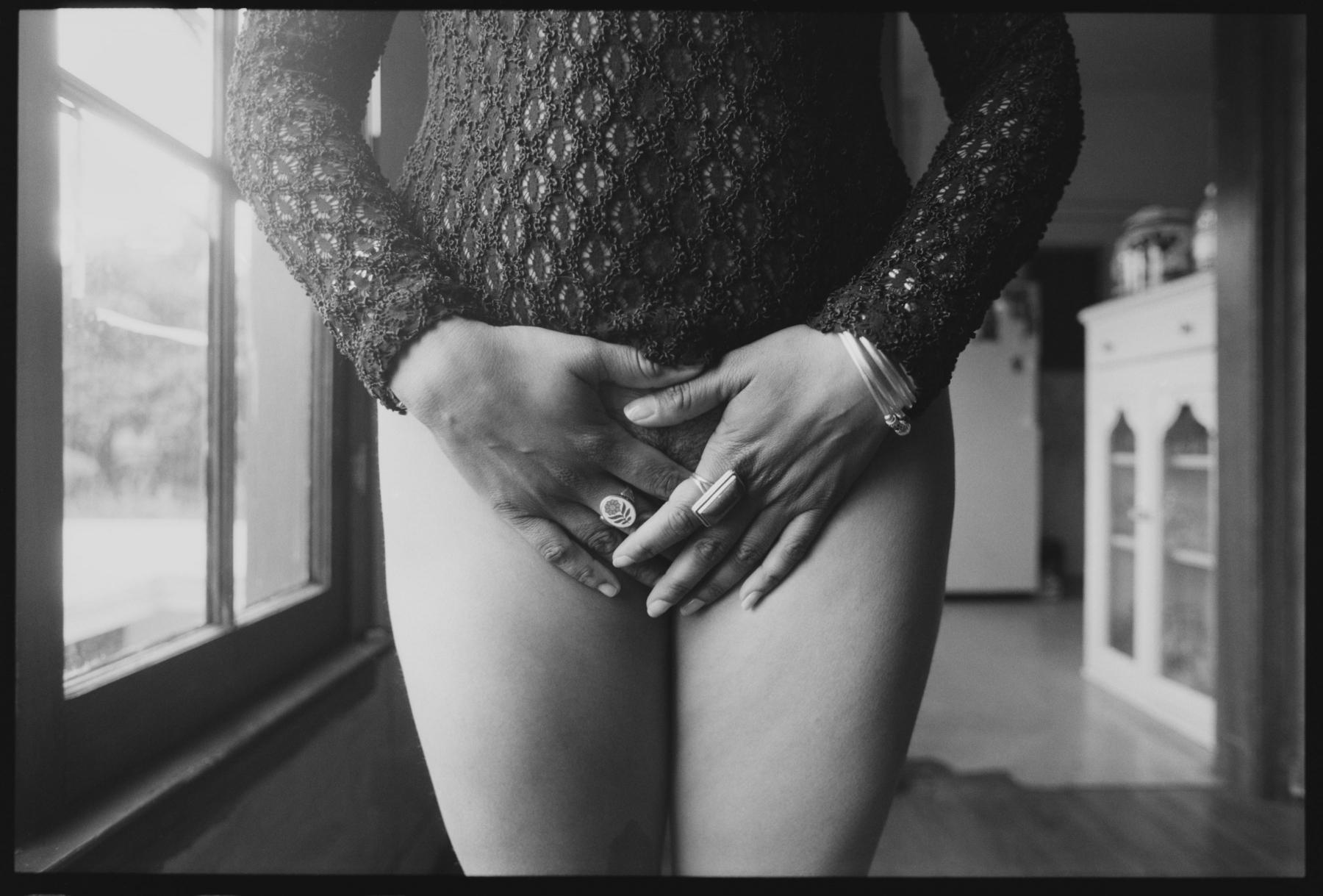

Reynaldo Rivera: Carla, Echo Park, 1997.

Reynaldo Rivera: Bianco, Reynaldo, Echo Park, ca. 1992.

Reynaldo Rivera: Patrons, Little Joy, 1996

Reynaldo Rivera: Pamela, Echo Park, ca. 1998

Reynaldo Rivera: Richard, downtown Los Angeles, 2023

Your photographs never feel exploitative. Maybe it’s because they were made for you, or come from within your world. How do you approach making work that feels that intimate?

It's not something you can approach. You have to really be in it, the moment, present. I never thought of those photographs as just portraits. When I was shooting in the clubs, the drag shows—all of that early work—it wasn’t about documenting “cross-dressers” or looking at anyone through some outsider lens. It was about giving people what they wanted: to see them as how they wanted to be seen. If someone believed they were a star, then that’s exactly how I photographed them. And, to me, they were stars. They were as grand as Marlene Dietrich or Faye Dunaway. Honestly, I’ve always thought the knock-offs were better anyway. Those performers were the leading stars in my movie, because everything was my movie. I tried to photograph them through their own eyes, to show them as they imagined themselves to be, not as I saw them. In those moments on stage, they fully believed in their own transformation. Back then, in the late eighties and early nineties, those backstage spaces were private and off-limits to most people. Many of the girls’ families didn’t even know about that part of their lives, and within the queer community they were still treated as outsiders. I only gained access because of a performer named Mrs. Alex, who invited me into the dressing room and told everyone to chill out because I was taking her picture. That’s where so many of my favorite photographs were made. Most of those women are gone now. They didn’t live to see the century turn, and that’s something that still breaks my heart.

It’s like you’re reading my mind because a thought I had about the photographs is that as beautiful as they are, there is also a darkness in them.

Mija, you’re Latina. You know death isn’t darkness. It’s part of life. It’s sad to me now, but at the time it barely registered, because when you’re young, life keeps moving; it doesn’t stop for anyone. Looking back, I get all dramática and tragic about it, because it’s heartbreaking that they never got to see what came after. I mean, what’s happening now with trans visibility—it’s still fucked up, but at least there’s a moment, a light, a kind of recognition. They never had that. They deserved to be celebrated, to have their moment in the spotlight, to feel, even for a second, like a whole bag of chips.

I also wanted to ask about your own role in the photographs. Because you not only take them, but you’re in many of them in very intimate situations.

I’m in it to win it. Well, mija, to be your true self, without shame, without apology, to own who you are and what you desire, whatever that looks like—can we dare to look at ourselves that way? To see through our own vision and strip away all the exterior shit we’ve learned along the way—all those ideas of who others think we are? That’s the hard part, especially for young people now. They’re bombarded by the media from every direction, constantly being told who they are, what they should want, what they should look like. It’s exhausting. It’s time to turn some of that noise off and figure out who we are—collectively, yes, but also individually. What does desire look like to you? Because it’s gotten blurry with all that fetishism, all that projection of what others think we’ve been. Does that make sense?

Because you’re very much involved in the photos as a participant, how do you negotiate that tension of being in them, but also being the one who is documenting those moments?

Bitch, I was having sex in those photos—I wasn’t negotiating anything, I just thought, oh my god, this looks cool.

You can see the one of Bianco fucking me—I’m in the mirror, and I just grabbed my camera as he was sticking it in and took the photo, boom. I think sex is one of those places where you become truly vulnerable. That’s one of the beautiful things about having sex with someone you’ve been with for a while—all those walls start to fall away. You get to a point where you can just be with each other without worrying you might fart or have bad breath or whatever else comes up at the beginning. Some of the images in the book are from that time—some from the early days, some later. There’s one image of Bianco’s back, taken in a mirror’s reflection—him lying there, his back exposed. I still remember what I felt when I took that photo. It was thrilling, but also full of anxiety and fear. One of my exes had just died of AIDS, and that shadow was always there. You can’t talk about art, photography, or anything queer from the ’80s or ’90s without reckoning with that reality.

How do you feel about the word archive?

Well, first, I never thought about any of this in those scholarly terms. Girl, I dropped out in the sixth grade—you think I was out here thinking about archives? No. Not at all. Now I do. I didn't have the language for it back then but I did know there was something there that made it art. So “archive”? No. But I did start to see the need for documenting by the 90s because so many people around me were disappearing—dying of AIDS and drug addiction. I began to see what I was doing as documenting something that was vanishing right in front of me. So in that sense, yes, I did start to think about saving it for the future. Because I thought this stuff was cool, important, and that younger generations should know we existed, that we did this. That was there. But eventually I had to step away—for my own sanity.

Your photographs feel protective but also deeply open—you really let us into everything. What do you think about the risk in that? There’s so much vulnerability in the work, and you’re putting so much of yourself out there.

I know. But, believe me, I’m afraid.

Why are you afraid?

My fear isn’t about showing myself—it’s about how the work will be perceived. I worry that people won’t really see it, that they’ll just reduce it to porn. I mean, I hope that whoever picks up this book is already in a different headspace, that they understand what it is. But still, that’s my fear—that someone will look at it and think, “Oh, this is just pornographic.” Because it’s not that. That was never the intention. Yes, the images are explicit—there’s a lot of cock and balls, sure—but it’s not about that. As strange as it sounds, even the act of turning the camera on myself was difficult. I can’t even look at some of those photos—they’re me, and still, it’s hard. But at the same time, I feel this need to break that shame, to break that fear, and just say, fuck it. I’ve lived my whole life that way, so why not end it that way too?

My fear at this moment is that it's exposing the community. We’re putting so much of our culture out there with Drag Race, Queer Eye, etc. Can it actually be making us vulnerable? How we’ve communicated and shared with each other is no longer just for us, it's mainstream now and that could be dangerous.

You really get a sense that there is a lot at stake in this work because you’re putting so much of yourself and your friends out there.

I’m not putting everything out there. The real, personal work feels like an exorcism for me. It’s a way to release the inner anxieties and fears I grew up with—being queer, loving men. I still remember the amazement I felt after being with a man, lying there and realizing how impossible that moment once seemed. I grew up in a small town in Mexico where being queer was worse than spitting on Jesus. As a kid, I never imagined I’d one day be holding a man, kissing him, feeling that closeness. Those moments felt miraculous to me. That’s the part that isn’t literally in the photographs, but somehow it is. Making these images was a way to purge those fears I was raised with. My mother—she’s still terrified that people will think she’s a lesbian. That fear runs deep. I think, in some way, all this work has been about breaking that chain.

It’s funny you ask about this, because I’ve never really let myself think about it—if I did, I’d probably stop the presses. The truth is, most of what’s in the book isn’t what most people would choose to show of themselves. None of it was put out because I thought we looked great or glamorous or any of that. In most cases, I just thought the photo itself was good—visually interesting. I really tried to remove myself from it, because otherwise, I don’t think I could have looked at it at all.

The essays in the book are very personal and provocative too. How did you decide on the writers?

A glad you mentioned this, because this book is as much about the writing as it is about the photographs. The people I invited to contribute are writers whose work often deals with love—its presence, its absence, the ways it connects or fails to connect us. I wanted to hear from them because I’ve always wanted to understand what makes people tick when it comes to love. What the fuck is love, anyway? It means something different to everyone. I wanted these writers to help me think through that. When I was a kid growing up in Mexico, in this little small town, I remember my first crush—we were in first grade, making out behind a book in class. I thought I was in love. I can barely remember his face now, but I remember that feeling of being happy. Of course, life had other plans. Things happened that made love feel more complicated, darker. Over time, all those experiences piled up and shaped what love means to me now. I think we all end up creating our own definition of it, piece by piece, from everything we live through.

The writing matches the photographs so well. It’s so in your face and direct. Just like the photographs. They’re not overpowering, it’s more like they flood you with emotion.

I love Devan Diaz’s piece. Constance’s piece is amazing. I included Abdellah Taïa because I had read his book Arab Melancholia and there is a scene in his book that I lived, and it was very emotional for me.

What is the scene?

He gets dragged—he gets assaulted by all these young men, in Morocco, in Casa Blanca, I think? And they drag him into this room, and they’re beating him, and they’re going to rape him. It has an unexpected turn at the end, but I won’t tell you. I don’t want to give away the ending.

Is there anything else you have coming up?

I’m having a show in Mexicali, mija. It will be at the art museum of La Universidad Autonoma de Baja California (UABC). It’s also called Propiedad Privada. I was born in Mexicali; it's in the middle of nowhere but I am very excited. The curator got a massive grant, so we can put together the show I wanted to put on.