Étant donnés exterior door, Marcel Duchamp, 1966, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo courtesy of Nicholas Heskes

I first encountered John Baldessari’s unrealized proposal for Information in Elena Filipovic’s book The Apparently Marginal Activities of Marcel Duchamp while researching Étant donnés. Known for his transformation from painter to proto-conceptual artist, before eventually appearing to abandon artmaking all together, Duchamp spent the last twenty years of his life secretly crafting Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau / 2° le gaz d'éclairage (1946-1966), a life-size diorama, inside an apartment accessible through the bathroom of his Greenwich Village studio. The work consists of two peepholes in an old wooden door ––one for each eye––which reveal a woman lying naked in a thicket of branches, legs splayed, holding a flickering lantern in her left hand. A waterfall sparkles as it cascades over mountains in the distance. Her head is hidden from view, and the single forced perspective of the peephole prevents the voyeur from looking at anything else.

Baldessari’s proposal makes its appearance in the chapter on Étant donnés in Filipovic’s book, with a full-page reproduction of the brief type-written document that encompasses the entirety of the artwork as it currently stands:

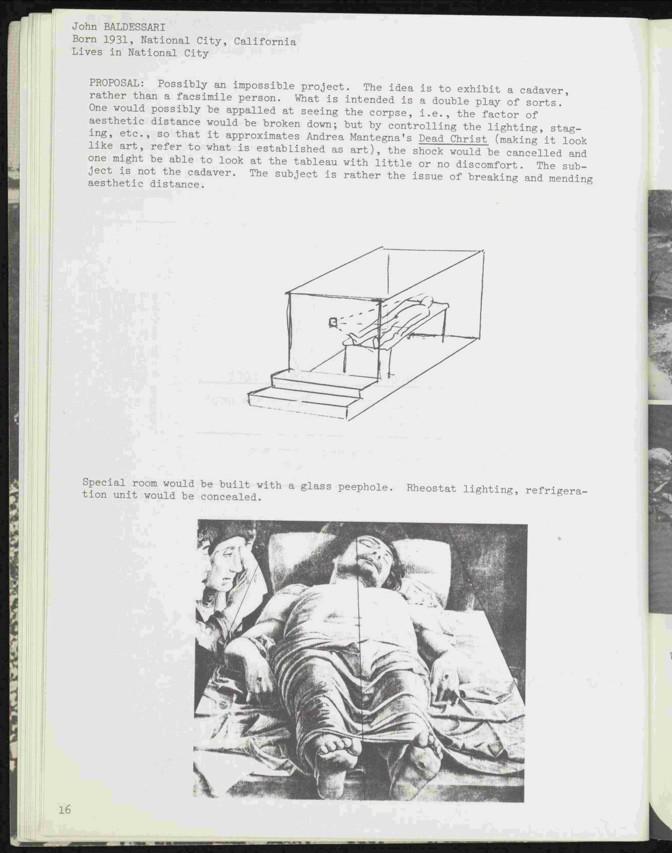

Possibly an impossible project. The idea is to exhibit a cadaver, rather than a facsimile person. What is intended is a double play of sorts. One would possibly be appalled at seeing the corpse, i.e., the factor of aesthetic distance would be broken down; but by controlling the lighting, staging, etc., so that it approximates Andrea Mantegna's Dead Christ (making it look like art, refer to what is established as art), the shock would be cancelled, and one might be able to look at the tableau with little or no discomfort. The subject is not the cadaver. The subject is rather the issue of breaking and mending aesthetic distance.1

Below the description, Baldessari includes a simple hand-drawn illustration of the “tableau” in a three-quarter view. A further note states that the box will be lit by rheostat lighting and equipped with a glass peephole and a concealed refrigeration unit. The document ends with a photographic reproduction of Mantegna’s painting with three perspective lines drawn across its surface, which correspond to three sight lines in the drawing that radiate out from the peephole over the body.

John Baldessari’s unrealized proposal for Information,1970

Unlike its most relevant sister works, Étant donnés and Paul Thek’s The Tomb (1967) (which now remains only in fragments), Baldessari’s proposal does away with the pretense of representation. While he insists that the subject is not the cadaver, the fact remains that this is why the proposal stands out. It is only through the cadaver that the “breaking and mending” of aesthetic distance could happen as described. Where Étant donnés has an obvious connection to the proposal through Duchamp’s use of the peephole and controlled perspective, Paul Thek’s life-like wax casting of his own body, maimed, comes quite close to the substance of Baldessari’s piece, and the material it aims to surpass. Thek’s wax sculptures, not just the “dead hippie” but also his Technological Reliquaries or “Meat Pieces,” in particular Warrior’s Leg (1966-1967), imitate flesh so realistically that one has to look very closely to see that they are fake. Once their artifice is noticed, the grotesque gives way to kitsch. What I find fascinating about Baldessari’s proposal is the maniacal compulsion to produce horror at the expense of art and the conditions that make it possible, for the sake of achieving the mythical self-transcendence that art often strives for. Where Thek succeeds by allowing a facsimile to stand between the viewer and the real thing, Baldessari fails by trying to unravel the distanced comfort of the art viewing spectator completely.

2.

In 1970, Kynaston McShine, then associate curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, arranged an international open call for proposals from artists producing work that broke from traditional forms of art making. This exhibition, titled “Information” was conceived as a broad survey of conceptual art that addressed the fraught political climate of the 1960s. In his essay from the exhibition catalog, McShine describes how young artists were now able to influence each other and society on a larger scale than previously imagined, thanks to new information technologies like television, film, satellite technology, and the “jet” (as McShine puts it).2 Hundreds of proposals were accepted for the exhibition and the survey marked a break-out moment for many artists, notable among them Hans Haacke, John Giorno, and Adrian Piper. John Baldessari submitted his proposal to be produced and exhibited in the gallery alongside these other artists’ work, but due to the nature of his material, the proposal was relegated to the exhibition catalog, a document conceived by McShine as a way to accommodate art that had no other clear mode of museum display. The proposal remained in purgatory here for decades.

It wasn’t until 2011, when curators Hans Ulrich Obrist and Klaus Biesenbach attempted to create John Baldessari’s unrealized proposal for 11 Rooms at The Manchester Gallery in London that it gained any real public interest. The exhibition, which featured a wide variety of performances, from banal to profane, was spread across eleven rooms and featured art that used the human body as a “material.” In keeping with this approach––of course Baldessari’s piece fit right in––the proposal was to be the exhibition’s grand finale after visitors passed through the first ten rooms. Unrealized Proposal for Cadaver Piece 1970/2011 failed like Baldessari’s proposal before it, though not for lack of trying. There were ultimately too many legal barriers preventing the success of the project, even after a great deal of effort on the part of several relatively anonymous administrators employed by the two curators. As Theron Schmidt argues in ‘Troublesome Professionals: On the Speculative Reality of Theatrical Labour,’ the frantic labor that went into acquiring a body in advance of the deadline for the opening became itself a performance piece. This curatorial hubris left the emails documenting the effort as the only material artwork they could exhibit in the gallery. Biesenbach laments in an email from May 10th, 2011, that “I am seriously worried that the point of John Baldessari’s piece is the courageous displacement of something that has no other place in society, neither profane nor art spheres anymore. If there is any way we could still achieve this, that would make the exhibition truly unique and groundbreaking.”

Donated medical cadavers, the only legal route towards acquiring a fresh corpse, are heavily regulated, requiring that the cadaver be used for scientific purposes and not art. The use of the cadaver has “no other place in society.” Or, as Baldessari insists: the subject is not the cadaver but “the issue of breaking and mending aesthetic distance.” The cadaver becomes central to the artwork the more persistently it fails to come into existence. Unlike other information art, which is ephemeral by design, Baldessari’s proposal stands out for its inability to escape ephemerality. Its status as information art is a forced condition. While the term “information art” encompasses a wide range of artworks and approaches to conceptual art, the particular understanding of information art I am referring to here was common across the Information exhibition. This was work that made use of new technologies of the time that allowed for rapid transmission of information, specifically through paper documents, telecommunication, film, or photography. In other words, the medium is always the message.

3.

When Andrea Mantegna painted his Dead Christ (1480), many artists were learning the fundamentals of human anatomy by examining and dissecting cadavers. Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti are of course the most well-known artists/anatomists to represent the human form after the careful dissection of cadavers. But there are many other instances of this type of artistic observation handed down to us by Giorgio Vasari in Lives of the Artists. Vasari notes that the first example of an artist using cadavers for personal study is the Florentine sculptor and printmaker Antonio Pollaiuolo, who skinned human bodies himself in order to study their musculature and passed this knowledge on to his students. Pollaiuolo’s print Battle of the Naked Men (c. 1470-1490) demonstrates the detailed knowledge of anatomy he acquired through these studies. The revival of cadaveric dissection during the Renaissance among barber surgeon’s and medical practitioners was driven primarily by these and other artists striving for realism in painting and sculpture. Their efforts eventually ossified with the publication of Andreas Vesalius’s anatomical magnum opus De Humani Corporis Fabrica in 1543, which combined significant artistic genius with precise scientific codification––thus establishing a foundation for what would later become modern medical science. But the road to Vesalius is strewn with examples of artists taking their thirst for realism too far. In 'Horror of Mimesis' art historian David Young Kim charts this theme, positioning excessive zeal for mimesis within the genre of horror as an aesthetic category. Kim highlights Vasari’s use of the Italian term orrore (horror, disgust) to describe forced encounters with the real, when fantasia (fantasy) and invenzione (invention) escape the bounds of artifice.

The more real one wanted to make an artwork, the more monstrous the process of realizing it became. Since refrigeration was not yet possible, cadavers for dissection had to be fresh. Often the bodies acquired by artists and universities for public or private dissection belonged to executed criminals, sometimes pulled green from the gallows. The veritable craze over this new practice led to grave robbing, and allegedly even murder, to meet its ends.3 Anatomy students became sick from prolonged exposure to skinned corpses, Vasari recounts a student of Guilio Clovio, Bartolomeo Torri, who kept limbs and body parts under his bed, Goltzius scavenged for corpses during a time of famine, and it was not unusual for artists to torture their models in order to capture the most authentic expressions, or like da Vinci, resort to other grim means for capturing an image.4 Michelangelo even is rumored to have killed one of his models by actually nailing him to a crucifix and stabbing him with a spear, in effect creating Christ in order to paint him.5

If one goes to such pains to represent the most life-like dead Christ, then why not skip the formality of painting the body all together? But then this is orrore isn’t it. In a tongue-in-cheek gesture, Baldessari mocks the notion of creating such a horrifyingly convincing imitation of life. The direct interaction with the legal apparatus that manages medical cadavers by Obrist and Biesenbach’s administrative team proves to some extent how far medical science and art have diverged since the Renaissance. Had they chosen to, they could have bypassed these systems illegally the way Michelangelo did before them. But Baldessari’s piece, had it been realized, would have subverted the expected relationship between artwork and model. This upending of painting's norms regarding anatomical models makes visible the dark side of the Renaissance ideal of naturalistic realism. The failure of the artwork to materialize reveals the nature of the limits imposed on art by social, political, and legal systems that always remain latent (even during the Renaissance no one would have accepted a cadaver as art). One faces here the old division between art itself and what we imagine is lying outside of it.

Andrea Mantegna Dead Christ and Three Mourners (c.1480), public domain, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Italy. Caption

4.

Baldessari’s rejected proposal shares with Étant donnés not only the feature of the peephole but also the ensnarement of a single human body made vulnerable by the peephole’s perspectival apparatus. In Étant donnés, the “carnal” vision is initiated by the sense that one is doing something inappropriate by looking at the vulva at the center of vision, and one is made aware of looking by not being able to see those in the room looking at them peering through the door.6 Baldessari’s piece would have produced a similar effect, but much more disturbing. Essential to this difference is not the cadaver against Duchamp’s clever facsimile, but the reference to Mantegna’s painting which exemplifies the connection between Christ’s body as a horrifying apparition and the technique of perspective drawing that grants the cadaver its importance.

Andrea Mantegna’s “Cristo in Scurto” or Foreshortened Christ, or Dead Christ and Three Mourners, but more often simply called the Dead Christ, portrays the dead body of Christ lying on the Stone of Unction after his crucifixion, where he will be anointed by mourners before being laid to rest inside the tomb. Among the many notable aspects of this painting, first is Mantegna’s use of multiple perspectival techniques to create a bizarrely foreshortened body that appears to break through the imaginary space between the viewer and the interior world of the frame. This is accomplished by Mantegna’s perspectival use of “orthogonals” or the lines parallel to the picture plane. Additionally, the photographic studies conducted by Robert Smith in 1973 show that the strange foreshortening of Christ’s body is only accurate as seen from 25 meters away. Cropped so to speak by the frame, with his feet extending past the stone almost touching the bottom of the frame, the body appears startlingly material.

Though the painting’s most challenging aspect is Christ’s foreshortened body, this is not its only idiosyncrasy. Mantegna’s uniquely morbid and somewhat pornographic rendering of the savior’s corpse is also unique. The body looks completely drained of blood and his wounds meticulously rendered with flesh-like accuracy. In addition, one cannot ignore the “crotch shot”, Christ’s genitals shaped by cloth lying dead center in the frame. Finally, predating Caravaggio’s Deposition (1604), Mantegna places the pierced undersides of Christ’s feet prominently in the foreground, a posture commonly reserved for ignoble casualties of war and misadventure.7 The combined effect of these pictorial elements situates Christ as an earthly victim of violence, abandoned by divine benevolence, before he is then redeemed through resurrection, making him more than a mere criminal executed by the state.8 His head is turned away from the mourners on his left to the empty darkness on his right, foreshadowing the flight of his soul.

In Baldessari’s piece, the image of Christ as an apparition would become actual, thus transforming him into a mere object. The artificiality of Christ is mocked by the idea that this apparition is just a trick, an assemblage pieced together from stolen cadavers. It draws attention to Christ's status in art history as at once an idea pulled through many layers of translation and as a body only discernable through traces of itself. Christ appears in the unrealized proposal as a description of a real corpse made up to look like an imitation of an interpretation of a description of a real corpse. At every turn on the journey of Christ’s image he must remain virtual as a trace of his persistently absent body. The indices of his touch imprint themselves on relics––the Stone of Unction saturated with blood, his face burned into the Shroud of Turin. While the true provenance of these relics is dubious, their value nevertheless lies in their mediated connection to Christ’s incarnate body. All of these layers of virtuality betray what is in the end a circle of phantoms that surround the threat of making actual what normally remains conceptual within the bounds of representation.