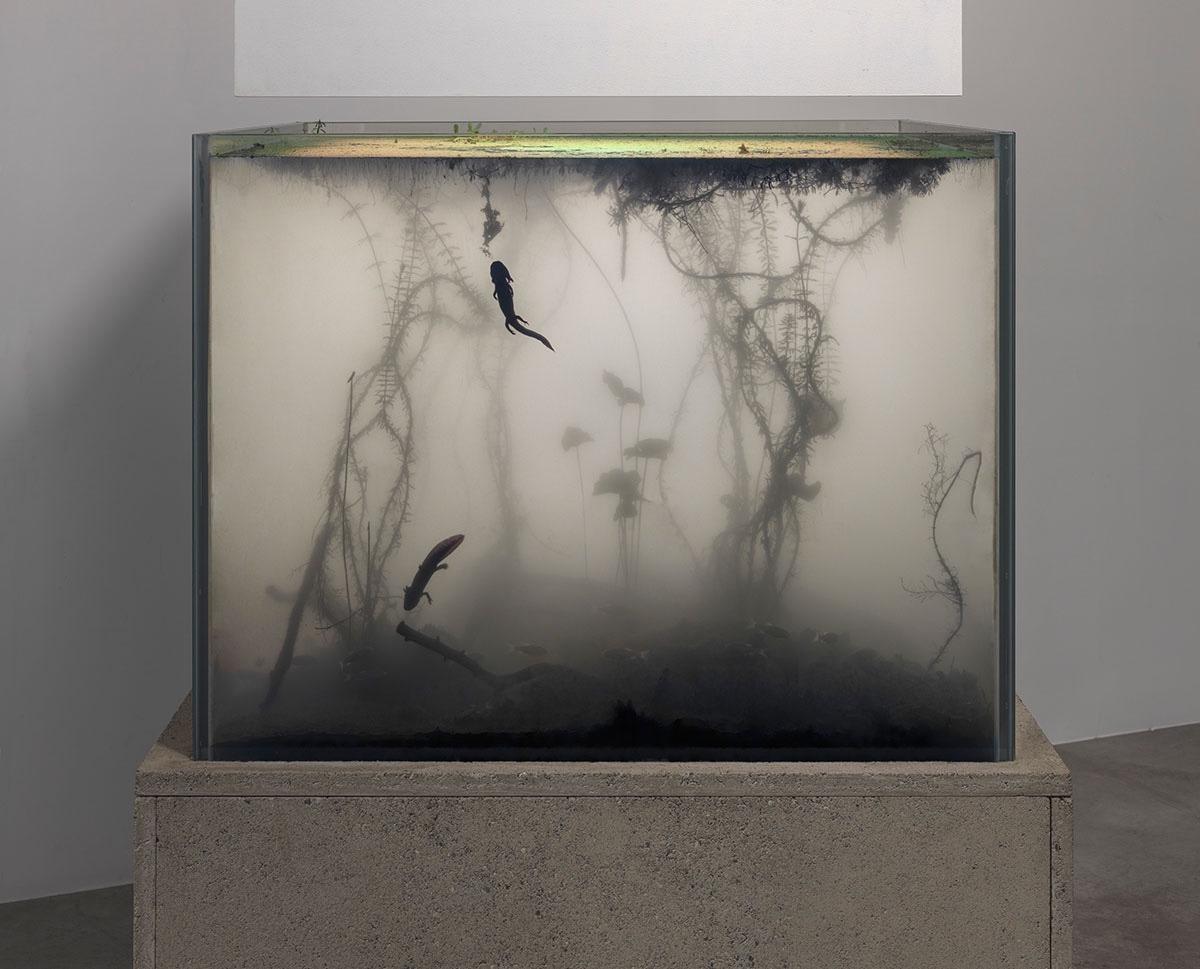

Pierre Huyghe, Nymphéas Transplant (14 -18), 2014. Live pond ecosystem, light box, switchable glass, concrete.

95 x 131 x 116 cm (aquarium). Sourced via.

At the back of the Manulife Centre, a luxury shopping mall along the “Mink Mile” in downtown Toronto, in an unassuming corridor of the movie theatre, is a piece of décor that is totally unremarkable for any corporate lobby, yet surprising when given a moment of pause: a saltwater fish tank, featuring a live coral reef. The fact that this and other publicly displayed aquaria have not yet been replaced with flat screens playing a 10-hour YouTube video on loop, “Best 4K Aquarium for Relaxation and Calm Sleep Music UHD,” stands out among today’s ornamental impulses, especially because of the murky challenge of keeping an aquarium’s micro-cosmos in delicate equilibrium (I say so, sadly, from experience). Aquarium fish remain ubiquitous in day-to-day life and are found in settings ranging from restaurant interiors, to tourist attractions, and medical waiting rooms. By sheer numbers, they are among the world’s most popular pets and comprise a multibillion-dollar industry, per a study of the global pet fish trade.

Aquarium fish are also popular subjects for contemporary artists, who represent them as objects of intrigue, romantic whimsy, and—occasionally—provocation. Some of the most vulgar, mass-market, and news-making contemporary art from the new millennium has involved fish. In 2000, shock artist Marco Evaristti made headlines when he set up an exhibit space with ten live blenders each filled with water and a goldfish. The museum’s director was later charged, but not convicted, of animal cruelty (a witness from the blender manufacturer testified the fish would have liquified instantly and therefore felt no pain). A similar backlash occurred more recently at the Jeonnam Museum of Art, where Yu Buk’s Fish sculpture involved goldfish placed in slowly emptying IV bags, supposedly representing “the collective trauma of COVID-19.” Of course, ask a stranger on the street to name a single piece of contemporary art, and they may very well tell you about a gaudy multimillion-dollar preserved shark. Why have aquaria endured as a popular form of art throughout history and across cultures? How do they confound usual divisions between professional and decorative art, or any easy definitions of kitsch, commodity, or artifice?

Aquaria inform without meaning to. They are romantic without commenting on industrial society and its malaise. They encourage contemplation about the natural world while not disguising their artifice. They are unremarkable, mass (and sometimes brutally) produced consumer products, but also infinitely unique.

The current moment is ripe for an interrogation of the art world’s relationship with other forms of life. Lately, parts of the internet have been chattering about the tiredness of current contemporary art, in response to well-circulated pieces by prominent critics, such as Dean Kissick’s “The Painted Protest” in Harper’s December 2024 issue, or Louis Bury’s overview of the phenomenon in “Is Art Criticism Getting More Conservative, or Just More Burnt Out?”. Plays on “more-than-human relations” in particular have become vessels for frustrations about the often-shoddy academic jargonification of art. For instance, Jaakko Pallasvuo’s satirical Instagram account, @avocado_ibuprofen, often skewers the proverbial “Nordic Institutional Moss Artist,” framing their work as a “stress response” to the complexity of the internet age, climate catastrophe, and the loss of once meaningful and supposedly more authentic connections and communities. Setting aside the perhaps reactionary impulses driving these discussions, these critiques do spotlight that environmental art and writing nowadays often makes overwrought and aspirational claims about how humanity’s relationship to “nature” should or could be. Fundamentally, it’s a mode that often offers its audience a bemused “what-if?” Although I am deeply unqualified to speak to the extent of this problem from an art historical perspective, I was not-so-long-ago neck deep in PhD-level research involving post-humanistic theories. More importantly, I now keep fish as a hobby. I therefore feel well positioned to make a different kind of case: the aquarium, as an art object, is a beacon for rejuvenating creative outputs in our time.

Amateur Fish

Fish tanks are among the oldest and most enduring forms of household décor. Thanks to the writings of Cicero, we know the wealthiest ancient Romans were pejoratively known as Piscinarii, or “fish-pond owners.” These aristocrats kept their prized lampreys and eels in open-air saltwater pools at their seaside villas as ostentatious displays of frivolity (these fish were likely unsold, rarely eaten, and maintained at great cost). The ponds were filled with boulders, seaweed, and sometimes extended from the mouths of grottos, all to foster a sense of naturalism. One nobleman, whose estate was located unfortunately far from the shore, spared no expense in having a channel cut through a mountain slope so his pond could be constantly replenished with fresh seawater—demonstrating a certain uncompromising commitment to creative practice. But the fish kept in these piscinae were more than just a costly display; Romans felt great emotional attachments with their fish. An emperor’s mother was rumoured to have adorned her favourite eel in jewelry, and one especially fish-forward senator apparently wept over the death of his beloved red mullet. Although these stories were likely plebeian roasts of the elite, they speak to the surprising obsessions fish tanks might inspire, along with the artifice of their naturalistic designs and inhabitants.1

In Imperial China, unlike Rome, keeping fish was not considered a status marker, although it was likely the leisure class that first brought them indoors during the Song dynasty (960–1279 AD), albeit in large ceramic vessels. Before then, the goldfish’s wild predecessors had been domesticated and bred for specific colourations as art objects for centuries in agricultural, and later, ornamental ponds. With the move indoors, people became more concerned with their fish’s well-being. The world’s earliest-known book on goldfish care was written around 1596, soon after the animals were brought into people’s homes. According to Yi-Fu Tuan, the founder of humanistic geography, these goldfish were domesticated on a different trajectory from dogs and other pets, because they were meant to be looked at, not lived with; “The fish in its aquarium, set upon a stool, is in its own world—one that does not impinge on ordinary human living space … The goldfish is also like an art object because new varieties can be produced so quickly through skilful human intervention.”2 Impatient with selective breeding, some fanciers even took matters into their own hands by drawing words, flowers, and other patterns directly onto the bodies of individual fish with paint or acid. Tuan argues that disdain for such “fakery” is misplaced because, whether through breeding or direct manipulation, domesticated fish are nonetheless creatures of artifice reflecting human tastes.

The aquarium as we know it today developed in Victorian England and America, a result of the newfound ability to mass-produce glass along with increasing trade and influence between East Asia, Europe, and North America. The first public aquaria opened in London and New York around the middle of the 19th century, and by the 1870s almost every major American city had its own. At the same time, fish became standard household pets in the West. The sudden trendiness of fishkeeping extended from the popularity of cabinets of curiosity and a society-wide push to systematically categorize new colonial possessions. Historical research suggests that it was also tied to a perceived loss of connection to the natural world in a rapidly industrializing society. A consumer industry emerged to service these new hobbyists, selling classic and kitschy ornaments like miniature castles and sunken ships. But professional aquarists and connoisseurs of the time derided such adornments as tacky, preferring pebbles and more seemingly authentic elements.3 From these origins, the aquarium has established itself, according to artist Antonia Bañados, as a seductive format “ambiguously placed between the scientific and the ornamental.” Beyond cultural considerations, this seductiveness is, no doubt, tied to an innate biophilia, or attraction of life to other life, as well as a preference for Heraclitean—or always changing but repetitive—motion. For example, a study examining biophilic design dryly claims that “pointing gestures trebled” after a store in a Viennese mall installed an aquarium in its window.

Some fishkeepers still concern themselves with the bounds of naturalism. On aquarium YouTube, an interview with the legendary owner of Ocean Aquarium in San Francisco, whose deep sand bed method has come to be associated with the city among hobbyists, has been viewed over 2.5 million times. In it, he demonstrates his low-tech setups to the audience, which rely on the filtration capabilities of plants and substrate. Meanwhile, TikTok user @cowturtle pushes past any easy definition of authenticity and artifice vis-à-vis “nature” with his own play on fish tanks as household art, in the form of a decidedly spooky and grotto-like pit of eels he keeps underneath his garage in Kentucky. Social media is full of all sorts of other fish-related detritus, replicated and circulated ad nauseam: photographs from a 2012 incident where a shark tank exploded in a Shanghai shopping centre make rounds across a network of vibe-based, vaguely techno-dystopian mood board accounts, and a fluorescent-lit wall of jellyfish at Toronto’s aquarium was designed as an interactive, purpose-built “instagrammable moment.”

In art critic Clement Greenberg’s canonical 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Greenberg sets up a binary between the two titular concepts, framing the former as any attempt to “imitate God by creating something valid solely on its own terms, in the way nature itself is valid,” and the latter as sensationalized, formulaic work that “can be turned out mechanically” and “demands nothing of its customers except their money—not even their time.” What my glancing overview of the history of aquaria shows is that their creators often aspire to imitate God through immersive naturalism, despite their status as a consumer product (I certainly thought I was playing God, or at least Fish Tycoon, when I started). Throughout history people have found ways to make the inhabitants of their tanks one-of-a-kind regardless of disparagement of purportedly tacky and artificial interventions, whether through selective breeding, ornaments, or more drastic techniques.

Professional Fish

Contemporary artists have used all manner of live animals in their works. Art historian and curator Luca Bochicchio traces a general move in the genre away from “ethical anthropomorphism” (what I see as a kind of charitable liberal attitude towards animals that highlights their human-like characteristics, thereby arguing for their progressive enfranchisement as rights-holding persons) towards “theriomorphism” (the ascription of animal characteristics to humans which decentres human frameworks for understanding the world). For example, Joseph Beuys, in his 1974 performance I Like America and America Likes Me, spent five days living with a coyote in a gallery space. Just over twenty years later, in 1997, Oleg Kulik, drawing inspiration from Beuys’ piece, instead spent two weeks living in and acting out the conditions of a caged dog in a piece titled I Bite America and America Bites Me.

This shift in attitude is also seen in works involving aquatic life. Environmental artist Natalie Jeremijenko designed seaweed bars that taste equally delicious to humans and fish, while clearing the water they are tossed in of toxic PCBs. In a recent example local to me, Lap-See Lam’s exhibition Floating Sea Palace, at The Powerplant in Toronto, used a blend of Cantonese shadow puppetry and recorded live-action performance to tell the story of a mythic human–fish hybrid voyaging aboard a ghostly, floating Chinese restaurant. Although the video installation was meant to allude to the kitsch spectacle of restaurant aquaria and their associations, and undoubtedly fits in the arc of theriomorphism, its overperformed acting and lack of live fish distracted from its appeal. Next time, I would recommend including a real aquarium, rather than the idea of one. Whereas, artists Mariele Neudecker and Pierre Huyghe manufacture scaled-down versions of the sublime in their respective works through alluring, otherworldly aquascapes. Of course, artists not working with aquaria as their medium also build beautiful, enthralling, self-contained worlds unto their own. One inspiring and clever use of live animals is from here to ear by composer and installation artist Céleste Boursier-Mougenot. from here to ear involves an aviary rather than an aquarium, inviting visitors to stroll through a lofty room filled with piles of sand, shrubby grasses, a set of instruments including cymbals, live electric guitars, basses, and amps—in addition to 70 live zebra finches. The birds flutter about their daily lives and produce a unique and ever-changing musical composition as they nest in the strings of the instruments. As a visitor, the experience achieves what aquarium-based art could only dream of—total theriomorphic immersion on the animal’s terms, without translation nor separation.

Inspirational Fish

A discussion of live fish in and as art could easily devolve into ethical questions about our relationships with other species. There is plenty to unpack, for instance, in the decision by multiple Italian cities to ban round fishbowls, because it gives fish “a distorted view of reality.” I tend to get mad when people tell me my fish don’t have feelings (although I don’t think embarrassment about their creative outputs is one of them), but I also know that a debate about subjects versus objects isn’t necessarily the most interesting or important way to think about fish in tanks as a form of household décor. Personally, I’m not a vegetarian—like those who accept the body of Christ, or cultures that eat their dead, I aspire to treat consuming and living with fish as a ritual sacrament. A few years ago, I learned that Japanese fishermen afflicted with mercury poisoning in the aftermath of a disastrous chemical spill into Minamata Bay framed fish as “co-sufferers.” Or as Jeremijenko might put it, “they’re not inhabiting a different world.” But unlike us, the fish we bring into our homes get to spend the next few, tumultuous years enveloped in tranquil, timeless beauty, as prisoners in their own palaces.

Aquaria inform without meaning to. They are romantic without commenting on industrial society and its malaise. They encourage contemplation about the natural world while not disguising their artifice. They are unremarkable, mass (and sometimes brutally) produced consumer products, but also infinitely unique. They are pretty in a literal sense—not cerebrally so. And their longevity through historical periods undermines critics’ prescriptions for something never-before seen. When thinking about how to move past stagnation, cultural producers might pay a visit to their local fish store.