.jpg)

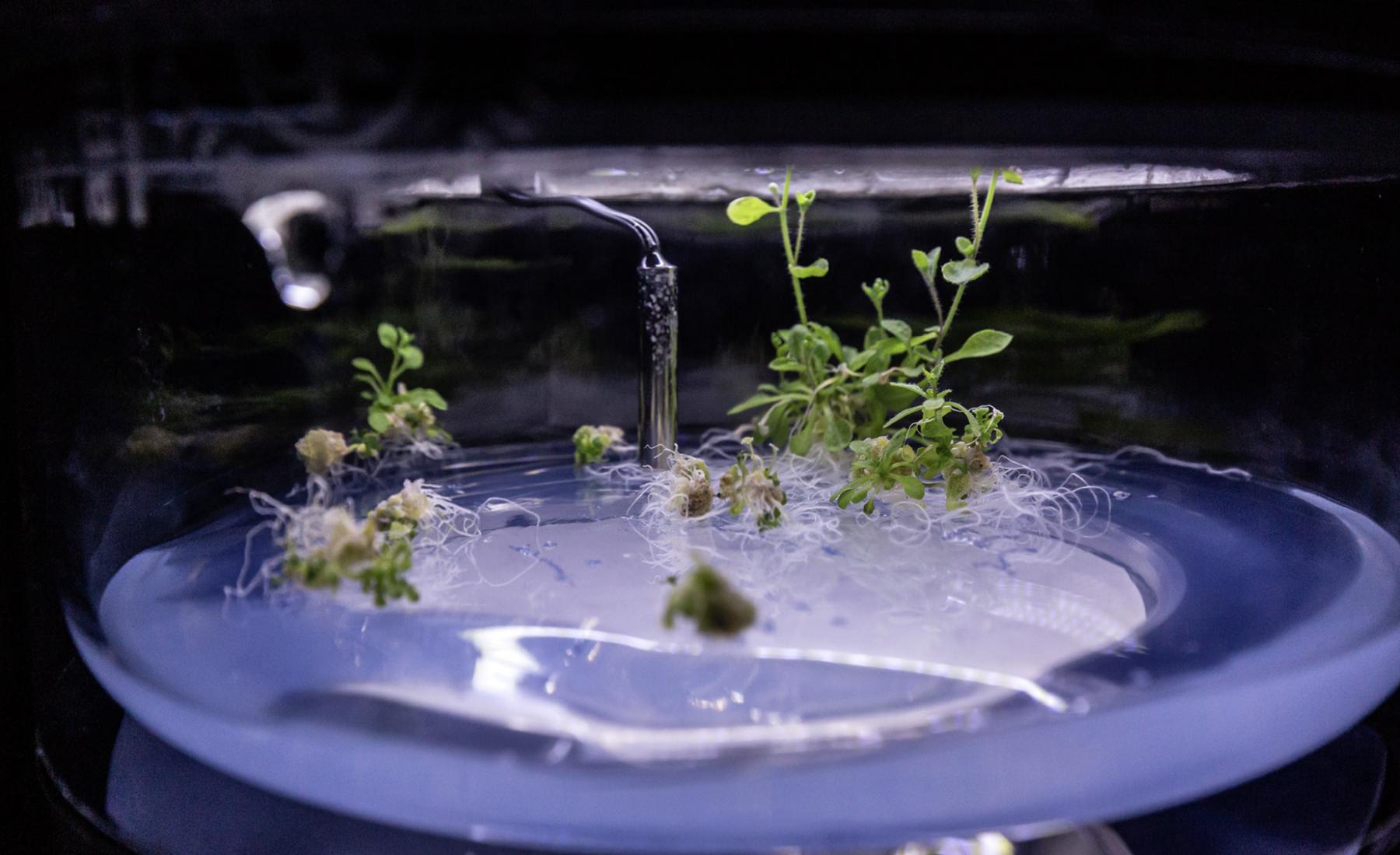

Carmen Argote, For Florence (2020). Cochineal on paper, duck leavings, urine and lake water. Documentation by Craig Kirk. Sourced via.

Urine is to be flushed and forgotten, concealed through elaborate infrastructures that buttress modernist fantasies of the human body as a sealed-off and self-contained vessel untainted by waste. And yet in the disavowal of the messy by-products of embodiment, these very systems attest to the transgressive threat of bodily fluids, which expose the ultimate limitations of control.

Urination—like defecation, perspiration, regurgitation, ejaculation, and lactation among other subtle and less subtle mechanisms of release—constitutes a mundane performance of corporeal porosity. Breaching the illusory boundary of the skin, urine evokes the necessarily dynamic constituency of ecologically enmeshed bodies. The slippery ontological status and the unruly materiality of urine render the substance particularly ripe for artistic inquiry.

The act of urination has been depicted in art for centuries, from Jerôme Duquesnoy’s oft cited landmark, Manneken Pis (1619), to Utagawa Kunisada’s erotic illustrations in Hyakki yaagyô (1825). Each rendering is a window into ever-evolving concepts of the body as a social actor, a biological entity, a spiritual vessel. In the Euro-Western annals of Modernism, artists like Paul Gauguin, Paul Klee, and later Pablo Picasso portrayed female subjects mid-stream, advancing entrenched binary associations with the particular leakiness of women—and women of color in particular—as subjects closer to the passive realm of nature.

The 1960s marked a shift from the visual representation to the direct material incorporation of urine among other fluids amid the rise of “Body Art.” Canonically speaking, postwar art involving excrement was dominated by male artists, with Jackson Pollock—looming as a mythologized predecessor—rumored to have urinated on several canvases as a hypermasculine gesture of defiance, combining splashes of piss and paint. Urine was channeled toward various aims, though often through provocative interventions charged with virility: the Viennese Actionists repeatedly leveraged streams of urine and semen alike in confrontational performances, while Tom Marioni chugged beer before peeing from a ladder into a metal bucket before a crowd in Piss Piece (1970) and Ed Ruscha employed urine as a (theoretically) neutralized mode of mark-making in Urine (Human) (1969), to name just a few examples.

By reckoning with relentless attempts to seal-off the individual body in order to shore up existing hierarchies, these artists question how such streams might be recirculated toward care as an urgent ecological praxis.

The cultural resonances of bodily fluids shifted in the 1990s amid the HIV/AIDS crisis. In an era of lethal government neglect in the United States, rampant homophobia fueled fears of contagion. During the so-called “Culture Wars”—an apt name for the militarized surge in the policing of bodily boundaries—the controversy and censorship of Robert Mapplethorpe’s Jim and Tom, Sausalito (1978) and, most famously, Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ (1987) reflect intensified patriarchal anxieties over the inability to control bodies that did not conform to heteronormative ideals. The conservative backlash against these photographs, which depict urination and urine respectively, in turn underscores the latent transgressive potential of leakage as a material-discursive threat to hegemonic order.

This essay considers the resurgence of urine as an artistic medium in the past decade, specifically through feminist and queer explorations of embodiment as an inherently ecologically oriented phenomenon. Following a 1993 group exhibition at the Whitney Museum, entitled Abject Art: Repulsion and Desire in American Art, abjection has been the dominant psychoanalytical framework applied to art involving biomatter. In her foundational text, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, Julia Kristeva defined abjection as the disgust or horror evoked by substances like urine that undermine tenuous distinctions between subject and object, self and other, purity and impurity, life and death. On one hand, this Kristevian concept is relevant to the following contemporary case studies that challenge the ontological stability of the individual human body as a sealed-off entity, while resisting the sanitizing tendencies of art. And yet this Eurocentric framework fails to account for the nuance of these recent interventions, which depart from the quintessential shock-factor of abject art. As Lindsay Kelley aptly articulates, “the abject threatens and contaminates, and so cannot account for a productive communicative entanglement of body and waste.” Artists such as Candice Lin and Mary Maggic shift beyond registers of repulsion to channel the generative potentials of urine as a tether that makes interdependencies of organisms within the ecosystem tangible. As a substance simultaneously intimate and planetary, urine prompts reckoning with the messy materiality of corporeal existence, denying patriarchal fantasies of disembodiment.

Candice Lin channeled urine toward a collective praxis of interspecies care in Memory (Study #2) (2016), which called on gallery employees to periodically mist their own urine over a bundle of lion’s mane mushrooms. Abandoning the preciousness of the vitrine, the fungi was situated in a plastic bag nested in a webbed ceramic vessel reminiscent of coral, a Chinese symbol of prosperity that simultaneously evokes colonial legacies of over-extraction. Through the mobilization of gallery employees as caretakers, Lin recalls the etymological roots of “curate” as “to care for,” complicating the erasure of the labor that maintains the art world. As such, Memory evokes feminist precedents such as Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s Transfer: The Maintenance of the Art Object (1973), which underscored the janitorial routines that preserve the sterility of the sanctified white cube. Lin pushes further, though, by challenging the implicit rules of such spaces through incorporation of urine as “matter out of place,”1 an unruly substance that insists on a politics of impurity.

Memory materializes interspecies co-constituency: human urine acts as sustenance for the lion’s mane, which in turn might serve as sustenance for humans (among other organisms) within endless cycles of microbial exchange. This tangible sense of reciprocity unsettles the taxonomic hierarchy of species underpinning human exceptionalism. The prospect of consumption instead reminds us of our interdependencies, lest we forget that “human” digestion is the collective labor of trillions of microbes that have persisted for millennia. Lin complicates anthropocentric notions of agency through the use of lion’s mane in particular: an edible mushroom prized for cognitive enhancement in traditional Chinese medicine. As the artist suggests, “when we ingest plants or think about their liveliness and ability to change us, we remember that we are not self-enclosed individuals in a case but are enmeshed and porous, effected and effecting.” As such, this ephemeral installation posits “memory” as an expansive phenomenon far exceeding any individual human, while denying linear concepts of temporal progress.

By invoking the interplay between growth and decay across species, Lin challenges modernist constructs of waste as “an unwanted surplus that needs to be contained by a variety of technologies and practices of ordering, management, separation, secretion or social categorisation.”2 Resisting such logics of control, Memory queers anthropocentric notions of use by mobilizing excremental fluids toward fungal growth—toward interspecies care. Artists Sophie Friedman-Pappas and TJ Shin likewise emphasize the contingency of “waste” by recalling longstanding applications of urine across cultures for centuries. Friedman-Pappas invokes tanning methods incorporating urine as a preservative to stabilize animal hides. In Salted Hide Pile (2021), the chemical alliance between human effluent and animal detritus foregrounds the cyclicality of all matter, denying linear capitalist logics of disposability. Shin meanwhile recalls dyeing techniques by utilizing urine as a mordant to enact crystalline forms on Petri dish-like ceramic plates in Astrological Botany (Artemisian & Quinine) (2023). Such legacies of urine in the production of indigo textiles—along with other colonial commodities like gunpowder and porcelain—evokes the material entanglement of bodies and bodily matter within imperial networks.

Through urine as an agent of transformation, these artists recall legacies of alchemy as an embodied proto-scientific practice historically marginalized by Enlightenment imperatives of rationality and rigid disciplinarity. Lin, for example, engages in an epistemological inquiry through herbalism not as an archaic mode but rather a persistent form of collective knowledge that counters the modernist trope of the (white, male) artist as a sovereign arbiter. As Lin notes, “you set up the scenario and make space for what you can’t explain, and at its best, the work goes beyond you.” This sentiment is echoed by Carmen Argote, who similarly embraces the sheer agency of her mundane materials in Urine Map in Book Form (2025), a floor-based installation leveraging the boundary-defying propensity of fluids to undermine cartography as an enterprise of colonial civilization. The artist relinquished control by urinating on a 30-foot piece of paper, allowing her fluids to react with tannic acid dye, iron powder, and crayon. In For Florence (2020), meanwhile, the mixture of Argote’s urine with water from a local human-constructed reservoir lends a sense of ecological situatedness, while playing upon the hubris of infrastructural efforts to impose order on fluidity. In turn, Argote mobilizes the individual human as a fluctuating body of water interconnected amongst other bodies of water, human and nonhuman alike, to recall Jasbir K. Puar's understanding that “multiple forms of matter can be bodies—bodies of water, cities, institutions, and so on.” Distinctions between “bodily fluids” and mere “fluids” become arbitrary, given the impossibility—the absurdity—of owning such substances, which resist logics of private property.

Brook Hsu, who similarly envisions her materials as collaborators, recalls the alchemist fable of turning base matter into gold by employing her urine to accelerate the oxidation of bronze. The artist recorded her diet while collecting her own pee to observe how particular foods altered the resulting patina in works like Earstick (2014-2019). Morag Keil likewise leveraged her urine as an oxidant in her Piss Paintings (all 2014), which collapse metabolic and artistic processes. The artist specifically invokes Andy Warhol, who famously called on his Factory assistants to urinate onto copper-primed canvases for his Oxidation series (1977-78), also known as his “Piss Paintings.” On one hand, Keil reinvigorates Warhol’s satirical send-up of Pollockian Ab-Ex machismo. Simultaneously, by urinating on copper sheets herself, she critiques phallocentrism. Her squatted streams result in alluring metallic pools rather than more spectacular—splashy, if you will—arrays. Etienne Chambaud likewise recalls Warhol, though while combining urine from coyotes, rabbits, elk and other animals. Nameless (2019) invokes the tactics of territorial marking and pheromonal signaling that evade human understanding through streams that deny straight-forward metonymic logics of indexicality.

Brook Hsu, Earstick, 2014-2019. Bronze, the artist's urine, acrylic plexiglass. 16 x 12 x 6 in. Sourced via.

Sophie Friedman Pappas, Salted Hide Pile, 2021, urine-tanned sheep hide, salt, watercolor, and wood. Installation view, The Devil You Know at Simone Subal Gallery, New York, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Simone Subal Gallery.

The projects thus far reflect renewed commitments to materiality, coinciding with the rise of New Materialisms, Object-Oriented Ontology, and posthumanist discourse more broadly. Alongside these artists reengaging alchemical techniques to foreground the cyclicality of matter, a parallel contingent has mobilized urine specifically in the context of biotechnology. With formal scientific training, artists Špela Petrič and Margherita Pevere focus on the hormonal contents of urine to explore intimacies across species, while navigating both the generative possibilities and the constraints of technoscience.

In Phytoteratology (2016), Petrič collaborated with scientists to cultivate a human–plant hybrid. The artist introduced hormones extracted from her urine to thale cress embryos then developed in an incubator, according to the logic that endocrine exposure would alter their morphology. Drawing on Karen Barad, Petrič emphasizes the communicative role of hormones as “harbingers of affective agential intra-action,” chemical signals that reflect the shared evolutionary origins of plants, animals, and humans alike. Simplistic notions of abjection prove rather irrelevant in this approach to urine. Here, it is a fluid repository of hormones that materializes interspecies connections beneath registers of human consciousness.

This open-ended project calls into question heteronormative constructs of human reproduction by reenvisioning parenthood beyond genetic inheritance as a patrimonial enterprise. By envisioning herself as a “biochemical co-mother”3 to the hybridized plants, Petrič posits a form of kinship beyond speciest rubrics, perhaps eliciting comparison with Lin. At once, though, the rhetoric of “co-parenting” prompts considering the power structures underlying this experiment, which risks reinscribing an anthropocentric gaze of control. Whether Petrič disrupts or perpetuates the tendency to treat plants as passive resources, however, this project raises the urgent epistemological question of whether the tools of biotechnology can be deployed without inadvertently affirming its technocratic logics. The interdisciplinarity of Phytoteratology is crucial here, insofar as Petrič leverages art’s refusal of empirical finality to push against the rigidity of modern science, leaving us to consider how established clinical protocols might be reoriented to privilege care.

In Wombs (2018-21), Pevere questions how her routine intake of a progestin-based contraceptive links her to other nonhuman organisms. The artist employs hormonal extracts from her urine to cultivate bacterial growth within hanging glass globules, underscoring the microbial interplay between humans and single-celled organisms. More broadly, Pevere prompts considering the complicated legacies of urine as a biochemical conduit between species, as exemplified by the case study of Premarin, a hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) derived from the urine of pregnant mares. For trans women, postmenopausal women, and others relying on hormone treatment, these conjugated equine estrogens provide a crucial form of care, while encapsulating the potential for queer interspecies interplay. At the same time, though, this vital drug depends on the reproductive exploitation of horses. Premarin thus reflects a world in which the furtive possibilities of interspecies intimacies coexist with hierarchies of subjugation. Personal pharmaceutical use is simultaneously entangled in broader ecological flows, as these same hormones inevitably enter rivers, soils, and food chains, commingling with environmental xenoestrogens, the ubiquitous synthetic compounds resulting from industrial and agricultural pollution. The unruly circulation of hormones far beyond human control renders toxicity constitutive rather than incidental to life.

Reveling precisely in this queer register of toxicity, Mary Maggic mobilizes urine as a hormonal vector in participatory projects like Molecular Queering Agency (2017), which culminates in “a urine-worship ritual that invites others to be colonized.” Housewives Making Drugs (2021) further explores urine as “evidence of our disobedient bodies,” given how organic and synthetic hormones intermingle in such streams. In this video, two trans women model DIY protocols for extracting estrogen from human urine utilizing only everyday materials. This project critiques systemic barriers to HRT under transphobic and exclusionary medical systems, evincing the potential to reorient the flows of biomatter away from capitalist instrumentalization. By reclaiming hormones as a site of queer experimentation and collective survival, Maggic rejects the bioessentialist logics that cast hormones as naturalized markers of sex.

If Petrič and Pevere reckon with the complexities of the mainstream biotech industry from within, Maggic more radically resists the epistemic grounds of techno-utopianism through speculative biohacking as a grassroots approach recalling the furtive spirit of alchemy. Locating hormone extraction in the intimate atmosphere of a colorful, cluttered kitchen—a domestic site long associated with feminized labor—this project satirizes clinical professionalism through the playful, informal tone of the performers. Through accompanying hands-on public workshops, Maggic commits to the collective cultivation of knowledge outside of hierarchical institutions, which Claire Pentecost terms “public amateurism.”4 Maggic models an ethics of biochemical kinship rooted in reciprocity and vulnerability as a shared—albeit never equal—reality of embodiment amid layered precarities. Care is neither abstracted nor sanitized here, but rather grounded in collective experimentation stripped of disciplinary rigidity.

These distinct projects explore the relational reaches of urine as a source of fungal sustenance, an alchemical collaborator, a biochemical conduit for kinship, a queer hormonal vector, and beyond. Whether recalling longstanding proto-scientific techniques or mobilizing cutting-edge clinical procedures, these artists channel urine as a politicized substance for navigating the politics of knowledge production. Taken together, these artists evince the material-discursive versatility of urine as an artistic medium that prompts thinking across scales of time, space, and matter—an exercise with the potential to complicate entrenched hierarchies, while revealing unexpected intimacies. By reckoning with relentless attempts to seal-off the individual body in order to shore up existing hierarchies, these artists question how such streams might be recirculated toward care as an urgent ecological praxis.