Katharine McKittrick. Photo by Ray Zilli.

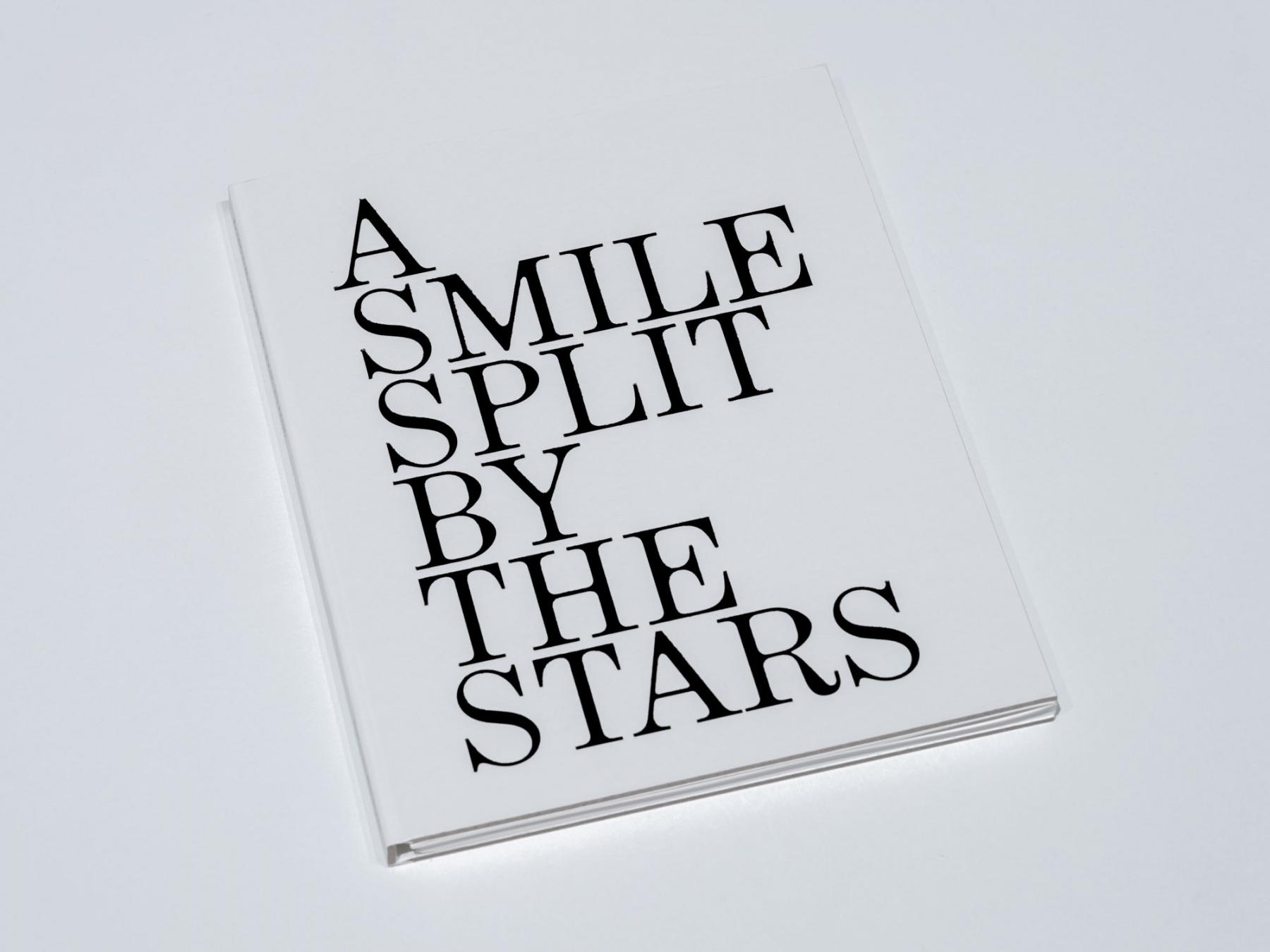

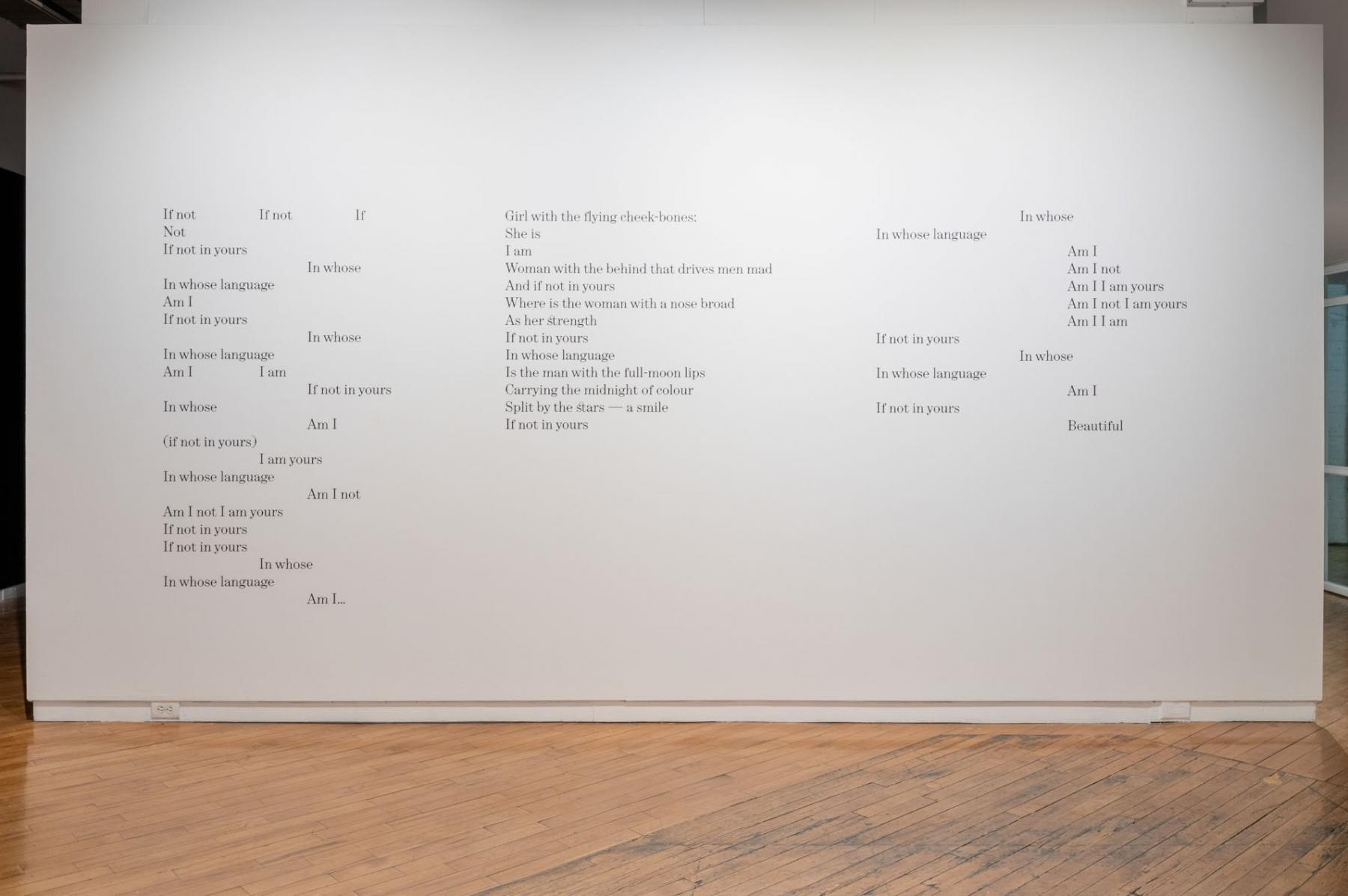

A Smile Split by the Stars: An Experiment by Katherine McKittrick is an exhibition that brings m. nourbeSe philip's poem "Meditation on the Declension of Beauty with the Girl with the Flying Cheek-bones" into two gallery spaces. Co-produced by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Gallery 44 Centre for Contemporary Photography, Revolutionary Demand for Happiness, and Modern Fuel Artist-Run Centre, the exhibition began with a conversation with Katherine McKittrick—Professor of Gender Studies and Canada Research Chair in Black Studies at Queen's University—during a rideshare in Kingston on our way back to campus where Katherine shared with me her love for the poem.

Katherine is the author of Dear Science and Other Stories and the foundational Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle, as well as editor and contributor to Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis. Beyond her scholarly work, Katherine loves bookmaking and often collaborates with artist and designer Cristian Ordóñez, most recently creating the limited-edition boxset Trick Not Telos (2023) and the hand-made Twenty Dreams (2024). Ordóñez also spearheaded the exhibition design for A Smile Split by the Stars.

At the heart of this project is Katherine's approach to practice and scholarship. As she writes in Dear Science, "Seeking liberation is rebellious," emphasizing that the goal is not to find liberation, but to seek it out. This process of seeking, what Katherine calls "method-making," generates the gathering of ideas and creates space where we can feel possibility together. The exhibition was curated by Katherine, myself, Sameen Mahboubi, and Ordóñez, and included the participation of poets, writers, and artists: Juliane Okot Bitek, Trish Salah, Cora Gilroy-Ware, Chloé Savoie-Bernard, Yaniya Lee, Aaliyah Strachan, Muna Dahir, and Roya DelSol. Through nourbeSe's poetry and Katherine's esteemed pedagogical practice, a space opened up for us to come together in ways that felt organic and meaningful, as though we had been working together for years.

This project came to me through Katherine, and in retrospect I feel that it came at the right time, bringing into view new questions and visions for what solidarity can build across histories and legacies of refusal and resistance: How do we feel liberation at a time like this? How can we speak of it when we are made spectators of unimaginable and unutterable violences? To seek liberation, as Katherine reminds us, is to condition spaces of generosity and commitment. This intention has affinities with the Palestinian concept sumud, which roughly translates to steadfastness and enduring defiance against any form of oppression, centering collectivity and community through shared solidarity. In some ways, this collaboration activated a kind of solidarity-relation, for Katherine and nourbeSe's writing and practice inspire processes from which we can feel the possibility of liberation at a time when it is seemingly unreachable.

This conversation took place in September 2025, in the weeks leading up to the installation and opening of the second iteration of A Smile Split by the Stars at Modern Fuel Artist-Run Centre.

Poetry teaches me how to read carefully, to pay attention to words and form, and to take that knowledge into the world. And so there's a lesson that the poet is also giving us that moves beyond the poem itself, which is: how do we read the world?

You've done so much in terms of inventing forms of practice for how to express your research and curiosities. For me, most importantly, what I've been learning from you is how liberation is entangled in these practices, in these methodologies, in these projects. My first question comes from something that really struck me. I think it was in Dear Science and Other Stories where you described your relationship with Sylvia Wynter—where you could “feel possibility,” and that connects you to feeling liberation. As I was reading it, I felt that liberation can always be in the space with us, that we can feel it alongside us and around us through these encounters that feel very important when thinking about building relationships and communities.

I thought maybe we could start by thinking about your line "seeking liberation is rebellious," but also in the context of your current curatorial experiment, A Smile Split by the Stars, and how you would connect these thoughts together: liberation, feeling, possibility, and the thinking behind this exhibition, this expansive collaborative project.

Thank you for all of this. I'm thinking about the moments I spent with Sylvia Wynter. When I was working on Being Human as Praxis, I would visit her in Oakland. She would have everything laid out on the table. I had three or four visits—that doesn't include telephone calls and emails—these meetings were onsite at her place. And I remember, and I say this in Dear Science, feeling like I'd been swimming for hours, noticing that there was a physiological response to having a conversation with someone who believes with all of her heart in a project of liberation that is based on her own analytical frame.

There’s something about watching someone work who is that committed—they actually change the vibe in the room and invite you into it. There's a generosity there that I cannot even explain, in addition to there being lots of food and intentional breaks. We'd be talking, talking, and then it's time for a break. That feeling—I wanted to try to carry it with me, and I still think about it almost every day. I think about it when I write, when I'm building projects, when I'm teaching. All of these different contexts where I'm not necessarily mimicking or emulating it, I'm doing it. A lot of her work is about doing the work. Part of doing the work is living like that. You embody it.

It's always been important to share these moments of liberation, whether through writing them down or through different kinds of art making, art practice, or essay writing. For me, interdisciplinarity is a big part of how we get there. You should be able to access these modes of liberation through any kind of creative venue. And for me, theory is creative. That's one of the other things I learned from Sylvia. She is writing creative texts and theory, both are interconnected. There's almost a seamlessness between expressing what liberation is and doing it, living it. For me, that is a revolutionary act. And I know in the conversation when you initiated this—I'm looking at our notes—you talked about how important language is to liberation, how important writing is to liberation, and how it's embedded in the work of pushing against genocide and war.

If we go back to that idea that we feel the work we do, that we're that committed, that we both embody it physiologically and express it—to take that away is a brutality. It's a level of violence that's hard to explain, but it makes sense. We see this with Indigenous communities in Canada, or with literacy work on plantations during slavery and being punished if you taught or learned reading and writing. How powerful is it to be able to, in the simplest way but also the most complex way—as bell hooks says—to talk back, right?

That's beautiful. It reminds me of Gaza and the West Bank having the highest literacy rate in the world and that being perceived as a threat from a colonial standpoint. The Political theorist, Dr. Karma Nabulsi, coined the term scholasticide to describe the deliberate killings of students and teachers, and the complete destruction of educational infrastructures and resources in Palestine.

A Smile Split by the Stars began with “Meditations on the Declension of Beauty by the Girl with the Flying Cheek-bones,” a poem by nourbeSe philip that you love. What has poetry done for you? How did you come to it in the first place? And then, thinking about this connection between language and form as we explored it in A Smile—how does poetry bring us to think through form as a kind of instigator for new language, new expression?

Yeah, exactly. Exactly. I came to poetry like most teenage girls, through Sylvia Plath. That's right. And I still have a book of her poetry on my bedside table, Ariel. I really adore her work. From there, I read some Ted Hughes, and then the world opened up with June Jordan and Lucille Clifton. I don't know what it was about Plath that I loved, but I've been thinking a lot about poetry as a form that allows us to…it’s hard to put into words. It’s a feeling and an invitation to not try to master something and own it in a colonial kind of way. I feel that way about music too. I think that in some poetry—I'm thinking about the poetic novel Coming through Slaughter by Ondaatje, but also poetry, like Zong!—there is narrative. There is a story, and it functions in a particular kind of way. But there are also these moments of rest. It's about feeling the world differently.

I don't want to fetishize it either. I don't want to be like: “and therefore we're free.” But something about poetry offers—I don't know what it is—this language of possibility, maybe.

Absolutely. I think about the poet Fargo Nissim Tbakhi and his piece “Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide,” and the novelist Isabella Hammad—particularly her reading on language—and some of the other work that I'm compelled by like Minor Detail by Adania Shibli. It feels like language is failing us because of the many genocides we are being made spectators of—another form of colonial violence. But when we experience the work of these writers, or the artists we love, or these poems we attach ourselves to—they challenge that limitation. They push against it. I often think that the work of the poet or artist is to connect us back to the possibilities of language as it is broken into or constructed in other forms…it's hard for me to articulate, because even when we're working within the same structure and grammar, there's still a release and an opening that happens within the strictures of language. That's what poets do—they create that sense of possibility.

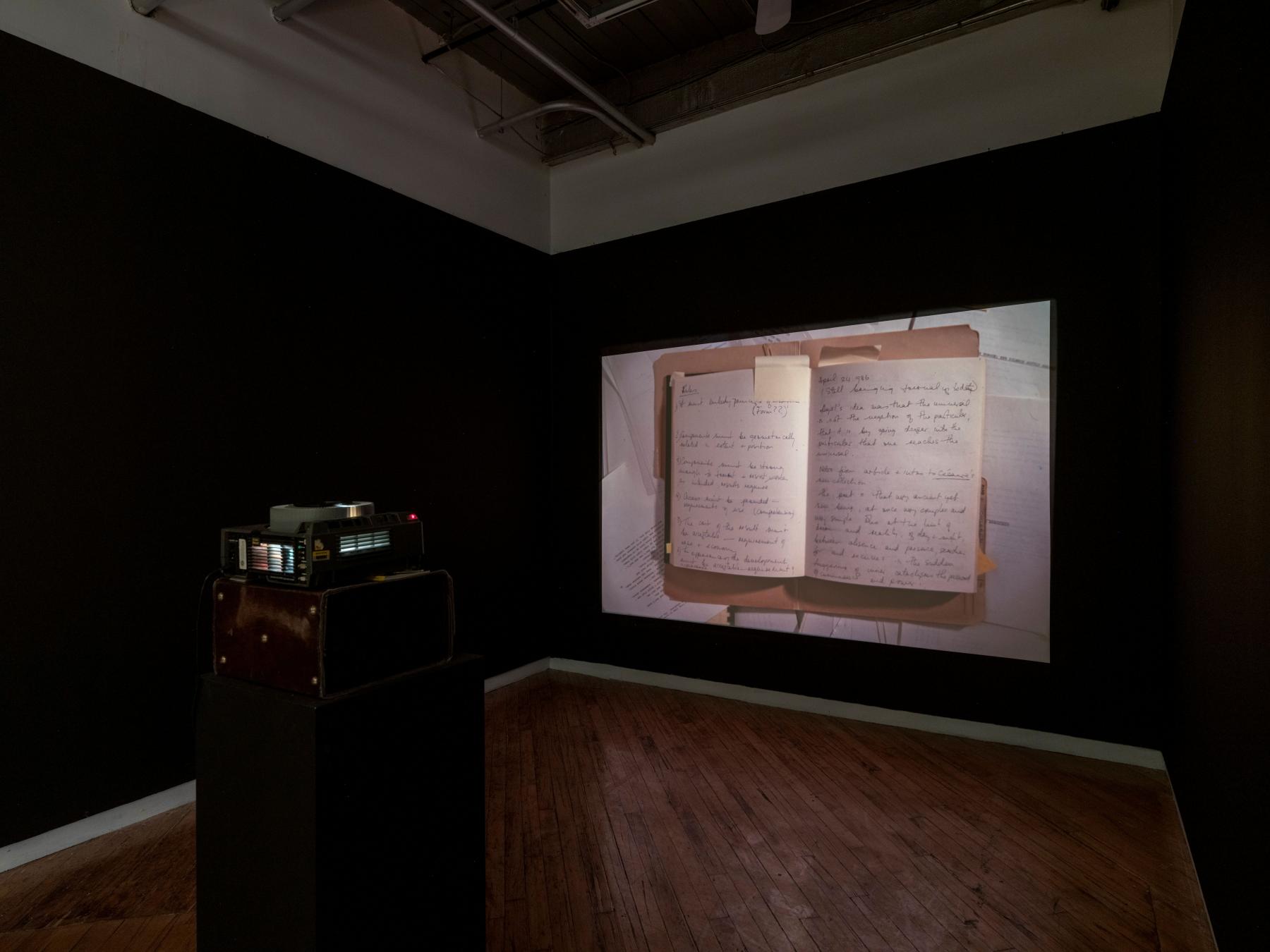

I think my attachment to “Meditations on the Declension of Beauty…” is this: I sat with that poem for twenty something years, and I have every version right here on my desk. It's not on my bedside. I couldn't get it out of my head because my mind wanted to feel like I could resolve something and either save the girl or figure her out. It took me reading nourbeSe alongside Sylvia Wynter to be able to come to terms with not just the contradiction of “Meditations on the Declension of Beauty…,” the contradictions of beauty in the world, and the word beautiful, but also to come to terms with my relationship with this poem. It's going to be long and forever, and I'm going to have to live with this. I’m going to have to live with this painful contradiction over and over and over again. I think that speaks to what you were saying about how to use this language that's breaking us, or how poets use this language that's breaking us, and produce something that's new; that is a completely different world. With A Smile, I felt like that, and I love how organically that project came together. Because it really was you and I in a rideshare, and a conversation with Naomi Okabe, this longer relationship I have with Cristian Ordóñez, Muna Dahir’s work with nourbeSe’s archive, and of course, nourbeSe and others. If I have to live with this poem in this way where it's sort of physiologically moving me, and it's sitting on my desk all the time, how do I bring in others to have a conversation about what this might look like? And that is the only way to do it for me. I'm not an expert on bookmaking, for example, or design or curation or nourbeSe’s archives. How do we make this a collaboration of friendships and possibility where we can honour this poem; and we all understand it in really, really different ways; and that's not a call for diversity?

Maybe a call for solidarity? You talk about collaboration: the way that you bring in other voices, and the way that you also bring in other elements into this exhibition. For example, there's such a crossover between an audio piece, the book, the poem itself, the posters, then the slideshow and the photographs of the archive. Collaboration builds on creating a model for what an exhibition can look like outside of any traditional or conventional way of doing things. I have said that it is important to get away from this binary idea that there's an artist and a curator. And now I feel with this exhibition we worked on together, all of those forms of authorial conventions have collapsed.

And as you’ve said before, “the poem is the artist.” I am very hip on citation practices, and when I was writing Dear Science, I thought a lot about this, and Sylvia Winter taught me this. Also, scholars like Lisa Lowe and Paul Gilroy. Everybody is part of the story, everybody. Like when I had Trish Salah, Juliane OKot Bitek, Cora Gilroy-Ware, and Chloé Savoie-Bernard read the poem into their iPhones, it was wild how different they were, and how the girl changed with every inflexion and every pause. They have to be acknowledged for their beautiful reading of this poem, and then to hear nourbeSe read it.

Yeah. Wow.

Well, how do you put that on a wall?

Exactly. Yeah. That's really the question, because it's really more about the space, more about creating a space for these voices to come into being together.

And do that horizontally as much as you can. So yeah, I like the idea of thinking about collaboration. I don't use the word solidarity much, and I don't know why, but I want to think about collaboration as solidarity as friendship. I adore Avery Gordon's work on radical friendship because she tells us it's clearly hard work—writing emails back and forth and doing it well–but also having these conversations where you might hate each other for a moment, because collaboration also isn't easy.

I think that this circles back to the relationship and conversations I had with Sylvia where I did feel like I was swimming forever. And I'm a terrible swimmer. I know how to swim, but I don't know how to swim well! Sitting at that table with her was hard—taking in, but also not fully understanding, her read of Frantz Fanon and others who have informed her work. Her generosity welcomed me in. How do we hold onto that in our friendships?

Yes. For me, friendships are like a navigational force, what’s to be is unknown. We're building together something we wish for that doesn't exist yet.

One of the pressures for me, with A Smile, was to show that language is pliable. Many academic interpretations of the poem imply that “Blackness is stable,” “Black femininity is a problem.” The analysis then moves to: how do we prove that the Black girl is the problem or how do we help her? And there's no capaciousness in terms of how the poet, in this case, nourbeSe, is using and reworking language and form to tell us that that's not what's happening to this girl, that there's something else happening. I can't fall into that trap of reading this poem as just a negative interpretation of Black femininity. Poetry teaches me how to read carefully, to pay attention to words and form, and to take that knowledge into the world. And so there's a lesson that the poet is also giving us that moves beyond the poem itself, which is: how do we read the world?

Yeah. I think that's key, we're not normalising the interpretations that are already actually concretized within a violent structure. And so, how do we read the poem by exposing that? And not just exposing it, but going beyond that, as you said, to find “a better way of reading before reading the world.”

I think there are layers. I think exposing it is one, and then we move. We do not necessarily move on, but we are inspired to do something. I think we also have to face that violence, right? We have to see it, it must move us into a different way of being. So how does poetry function in relation to harm?

That's why the work of images for me is so important. In the context of Palestine—in terms of the images that are coming out of Palestine, especially now—these images of endless unnameable violence. How do images function as a language system? And how do Palestinians, who are the ones on the ground documenting and recording the genocide—recording-in-real-time in order to show the world the reality on the ground—use images to counter genocidal logic?

Yeah, yeah. Yeah.

.jpg)

Installation view, A Smile Split by the Stars: An Experiment by Katherine McKittrick, 2025.

Photos courtesy of Darren Rigo, Gallery 44, Centre for Contemporary Photography.

Installation view, A Smile Split by the Stars: An Experiment by Katherine McKittrick, 2025.

Photos courtesy of Darren Rigo, Gallery 44, Centre for Contemporary Photography.

Installation view, A Smile Split by the Stars: An Experiment by Katherine McKittrick, 2025.

Photos courtesy of Darren Rigo, Gallery 44, Centre for Contemporary Photography.

Installation view, A Smile Split by the Stars: An Experiment by Katherine McKittrick, 2025.

Photos courtesy of Darren Rigo, Gallery 44, Centre for Contemporary Photography.

I can't believe I haven't asked you this yet. Why did you pick this particular reading by Sylvia Winter to be part of the Reading Session program for A Smile?

Oh, “We must sit down together and talk about a little culture?”

Yeah.

I picked it because I think it’s a perfectly written essay on literary criticism. I was afraid of positioning the girl in the poem as a victim who needed to be saved. I was afraid of being weighed down by dominant beauty standards! I reread “We must sit down...” and Sylvia had the tools to help me. They were just thrown in front of me. I rely on Sylvia as my analytical lens across a lot of my work because she approaches reading so uniquely. She enters every conversation with what she describes as that “third option”: not oppression or resistance, but something else. She is asking how do we figure this out beyond the normalized options doled out by monohumanism? With these kinds of tools, we do not fall into conceptual or analytical traps that assume the girl, in advance, is a degraded victim. The other thing I really adore about that piece—I think it’s written in 1967—is that it’s very smart around the great George Lamming and The Pleasures of Exile and his brilliance there. It's a model I think we don't see anymore. I don't want to be nostalgic, but why aren't we reading shit like this anymore? And writing essays that so carefully read and write out the stakes of culture in post-plantation contexts?

When we first read it together back in April, I couldn’t stop thinking about how timely it was that we were reading it. And that’s why now we're doing two sessions on Reading Palestine through and with Wynter. All I could think about was Palestine while I was reading it. There is a throughline that's like: no, if you're dealing with culture in any form, that has to be connected to what's going on in the reality we’re living through. I think it stands to the trauma of our times.

Yeah. I think one of the reasons—I remember in the session, and I actually wrote it down on a post-it note, something that you said, which I won't be able to find—is that question, how do we read Palestine through Wynter? I think that's what our sessions on Palestine are about. It’s simplistic to read Wynter and suggest she doesn’t attend to Palestine and complain about it, rather than taking up her intellectual call, and the intellectual tools she’s giving us to work through this harm. Right now, this world is fascistic. It's fucking awful. So if we're going to just sit around and say, Wynter doesn't talk about Palestine, I am not interested in that conversation.

Yeah, wow.

I wanted to end with this: How do you see this exhibition, or the process of putting it together—especially now that we've done one in Toronto, we did one in Kingston, there might be one in Montreal, and it might also become a book at some point, a different book than the one in the exhibition—what is inspiring you to keep going with it?

One of the things I learned when we talked about the space in Kingston is that we have to revise it, that it can't be the same as it was at Gallery 44. Early on at Modern Fuel, I was mourning the loss of the Gallery 44 space. But things shifted quickly when we—you, me, Maddi (Andrews, Executive Director of Modern Fuel) and Cristian—began to work with the new space. We needed to remake the path through the story we are telling. We had to reinterpret what the work sounds and looks like. In this way it is living, and I love that it's living. The most important thing to me that I've learned about Black geographies and theorising a Black sense of space is that geography is an activity rather than a stable location. If it's an activity, then as our curations and conversations about this poem fade they also renew. The other part of the story for me is the collaboration. I don't think I've ever worked with better people in my life. Putting this project together was so easy for me because I became “we.” I had a crew of cools. I'm so lucky. I've said this before: I'm so lucky with my friendships, and I'm so lucky that I've built new friendships with this project. I feel happy that I can be in conversation with people. And we're all, we all have our weird personalities and everything, but wow. You remember when Cristian showed us what the first exhibition design might look like? And we were all like, okay, that's great—fin! It was so beautiful. It was really beautiful. Beautiful. Yeah. Commitment is beautiful. So, I think the collaboration has been—also just, yeah. I just feel so lucky. I'm so lucky.