As with most cultural corners, politics has found its way into nightlife. In a world that presses its dominance upon those who’s self-hood runs contrary to the norm, a life of compromise and constriction becomes the known reality. Since the onset of the AIDS pandemic in the 1980s, the night time became a release, shield, and celebration of self without bounds. As much as nightlife culture in the eighties provided an escape, it also became a forum for education on safer sex practices and forming a community. This was especially true for marginalized queer and identity-agnostic individuals. Dances parties and off-grid gathering centers became spaces for advocacy and combatting stigma around HIV/AIDS. These spaces continue to have an intergenerational significance and influence as sites for fostering one’s subjectivity and freedom. Despite horrifying events like the mass shooting at Orlando’s Pulse Nightclub, only two years ago, the pain did not defeat but only galvanized and band together queer communities all over. More than ever, the dancefloor became a site of defiance to party with a purpose and a transformed sense of community.

With all this considered, artist/educator Harold Offeh is making a case for these spaces in an oncoming participatory performance in association with Nuit Blanche Toronto. Offeh deliberates the temporality of these spaces in the face of displacement of underground and club culture through gentrification. He considers how the night-time economy like the cost of transportation or cost of entry fee ultimately impacts the prevalence of these liberatory spaces. Often pulling from archives and fragments for popular culture, he comes to this project with inquires; exploring the possibilities of multi-diverging narratives in the digital context and how the body can an ever-evolving site of knowledge and an archive of its own. Our conversation with Offeh not only discusses this, but we also talk about his amassed rich history of art-making including his recent Reading the Realness.

the idea of the night, covertness, and being able to form a community, or exist in a different space to the regimes that are imposed on to the daytime--I think it’s inherently subversive. It is significant that there are these manifestations in a queer culture that can only exist in the night away from the clarity and authority the daytime brings.

How did you get involved with this project for Nuit Blanche Toronto?

One of the curators they invited was Karen Alexander who I knew, and she approached me about it. We had discussions about a work that will be responding to the city and thinking about a work that runs over twelve hours. It will engage with public space, architecture, and the city. What I’ve been trying to do is find a particular approach to the project that is relevant to what I already do. Quite often in my work, I’m thinking about histories and archives and fragments of popular culture and I’ve been trying to connect that in the context of Toronto.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the night-time economy and the night-time culture and how within the context of London there’s been a displacement of underground and club culture through gentrification. And a couple of years ago when we had a new major, he appointed a nighttime Tsar to kind of develop a strategy for the night-time economy-

Did you say a Tsar?

Yeah, it’s a weird term, I think its American. As in the Tsar of Russia or something. The Emperor of Russia; the Tsar. They use that term to appoint their strategic advisers that have responsibilities for a specific role. Like the mayor will appoint a crime Tsar who will try and reduce crime. So, this nighttime Tsar who is really interesting and is someone I know, she’s called Amy Lame. She is a club hostess for this queer club and LGBTQ activist. She’s someone who has run a club for like 18 years in London and she has this oversight, strategic role in thinking about transport and its impact on night time entertainment. Anyways, I was thinking about some of these questions in the context of Toronto. Also thinking about what makes up the night-time economy and night-time culture within the urban context. The project has been developed around that; queer economy, queer labour, and how that seems to be shifting histories but as it relates to current discussions in Toronto. And the project I’m developing is trying to capture that a little bit.

You mentioned you work with archives and histories; given that you are currently preparing for the project in the fall and that you are currently working outside of the site, where have you been digging for information?

Initially, the research has come out of proposing a series of questions and accessing particular networks; I’ve been put in touch with various figures in the Toronto scene like the amazing artist called Tobaron Waxman who has been incredibly helpful as a kind of linchpin figure who has directed me and set up various conversations. I’ve also harnessed social media, and one of the surprising things for me is how amazingly generous people have been. Each person I’ve spoken to gave me the names of another five different people, and when you speak to them they have another five and I’m still processing all of that. It’s a wealth of material and it’s helped me think about my position as an outsider coming into this. I think what that affords is I’m not coming with any allegiances, I’m not coming in with a particular agenda and I think coming from a place of not knowing is enabling at this point. I’ve been trying to develop a structure that somehow might reflect these people who have been generous with their stories.

How do you think about the archive in comparison to social media, which is something that is generated by a stream of individuals as opposed to the archive which is one defined entity?

I’m really interested in how one defines what the archive is and its institutional framework which can often be problematic. I also think about how archives operate in relation to fixing narratives and histories in terms of what deserves to be conserved and what then becomes a part of a body of knowledge and becomes orthodoxy. I’m interested in how that can be challenged in a digital context where there are multi-narratives and histories that are spread out there. The idea to capture that seems almost impossible. It’s more about a flux and interflow.

One of the things I’ve been thinking about is what a live, living archive would look like in terms of the archive as a body, as an experience, or encountering it as a situation. For example, I think about the book Fahrenheit 451, where in the future, all books are burned but there’s a resistance where there are people who live on the margins of society and memorize books. So, if you want to experience culture or literature, you have to find an individual to recite it to you. And so it’s that idea of the body becoming an archive. Inherently, that is perhaps unstable because that person might not remember everything, but there’s an opportunity to have a conversation with that person, and to question and think about how the work is brought back for a retelling. For me, that becomes an alternative archive. It’s something I’ve been trying to think through with this project for Toronto.

So you’ve talked a bit about nightlife as central to this project. But why the night time? What is its relationship to the queer experience?

Well, it has to do with histories of oppression, prejudice, shame. The idea of the night, covertness, and being able to form a community, or exist in a different space to the regimes that are imposed on to the daytime--I think it’s inherently subversive. It is significant that there are these manifestations in a queer culture that can only exist in the night away from the clarity and authority the daytime brings. For me, that became resonant in thinking about this period between 7pm to 7am.

You are clearly thinking about a lot of things for this project, but what kind of form of the work will take?

At the moment, the title is ‘Down at the Twilight Zone’, and I think it’s going to be something that’s going to look like a party. I’ve been thinking about an event that’s structured by dividing the twelve hours into chapters. I’ve broken down the time period into four thematic chapters that would broadly look at different areas of queer culture. I’m interested in the idea of what a live queer archive would look like in terms of dance, touch, and movement.

For me, it’s important to really think about the fact that queer histories don’t just belong to queer communities. I think they have to fit into the broader narratives of the life of a city.

So in many ways, you are taking a culture/history that is “underground” and making it a participatory sharing activity.

Yes, and there are inherent issues with that. One of the ways we’ve been trying to think around that is the spaces that it might be staged in, and it’s not completely resolved. For me, the venue should be somewhere where you experience queer culture, which is often an offbeat and abandoned space that is then reclaimed and holds that kind of history. The setting of the work has to articulate that. I’m also aware that lots of people who I’ve spoken to across queer communities don’t engage in these events because it's mainstream and they see that as being a turn-off. That’s already something I’m thinking about.

What do you think about the idea of mainstreaming queer experiences? Is that something you think queer individuals aspire to?

I think there’s a full spectrum. Some people believe it is important that it is an alternative separate culture that isn’t subject to heteronormative paradigms if you want to call them that. There’s also the thing about not using the term ‘queer community,’ but to have it be pluralised ‘queer communities’. In that, there are various spectrums. One of the things I’m aware of that I also think is important but go back and forth on, is the need for essentialising culture in order to find, I have an issue with the term but let’s say ‘safe spaces.’

I think when the terms of reference, for example with this festival which is a municipal festival sponsored by the city and its parameters, are inclusiveness. So, the idea is that because it’s using city funding, it’s aiming to bring culture to the broadest possible audience and that includes queer communities. And I think if one then begins to promote an argument where one excludes oneself from that, then the logic of that becomes problematic. It’s also like you are disentitling yourself because you are saying ‘I don’t want to be visible or constituted within a broad spectrum of the city and a broad definition of a city.’ For me, it’s important to really think about the fact that queer histories don’t just belong to queer communities. I think they have to fit into the broader narratives of the life of a city. If I live in a city, my ethnicity or sexual orientation does not put boundaries on the culture that I engage with. I might live in a Polish neighborhood and the fact that I live there means I’m intersecting with those histories. In some ways, I can have some ownership over those histories through proximity. It will seem problematic to say ‘oh no, I’m black, and that’s Polish so can’t engage with that.’ I think it’s important to recognize the multiplicity of narratives that go into making this kind of homogeneous thing that is a city. I think there’s a danger in essentialising a culture. When that happens, you remove that narrative and we are left with patriarchal hegemonic narratives. For me, a political project will be to queer spaces in terms of adding those layers of narratives. But it's contested and I’m happy to have those conversations.

As a queer British individual, what do you think you can personally bring forth into a Canadian context?

What’s obviously shared is the experience of colonialism, the structures, and narratives that brings with it. Toronto has an immigrant culture in terms of these waves and layers of immigrant experiences, which is something that I am very live to and is my experience. My family is from Ghana, I was born there and came to the UK as a small kid. I grew up in London and in a very diverse area of North London. I carried with me that pull of experiences of people inhabiting multiple cultures in the same space. In the UK, partly because of Brexit, there’s a conversation about defining Britishness in opposition to a connection to Europe. There’s a conversation about Britain’s place in the world.

Selfie Choreography: Performing with the Camera

A Workshop presented for LOST SENSES at Guest Projects, London 2017

Let’s switch here. I was looking at your body of work and thinking about how much work you’ve done, and it’s an incredible amount. You really have a compelling wealth of work and I didn’t really know where to begin. But let’s go back to where this impetus for critically observing yourself within an art historical context and within the contemporary art setting you operate in came from?

I think operating within contemporary art came later. But I was lucky, I went to a really good high school. I benefited from good teachers and a really good environment. I was encouraged to explore ideas of identity and representation within the realms of making work at a very young age. I remember writing a paper when I was in high school which I still have about the lack of black artists in the Tate collection, and this was in the early 90s. I remember my teacher really encouraging me to write to artists and galleries. And I remember writing to all these artists and they wrote back to me, including some major artists like Lubaina Himid who just won the Turner Prize. I still have her letter from 20 years ago. In this letter, we have an exchange about the Tate’s acquisition policy and lack of representation in curatorial departments. I was around the age of 17 and that’s made me very conscious of the value of education. It’s one of the reasons why teaching and learning environments are a big part of my practice because I think a good educational experience affords so much. And so, as a formative experience, I have always used art to explore questions. For most people making art is drawing a fruit, not necessarily intellectualized in any particular way. But I also quite naively fell into things.

But I also feel like you as a person have to be responsive to the environment that you are situated in.

I think it’s a degree of curiosity. I’ve always been questioning and wanting to find out about stuff.

Your body is central to your work and there are a lot of exploitative costs associated with presenting the body, especially through images where audiences might feel entitled to your body.

In some ways, I just fell into it out of expediency and convenience. It was really a desire to make or enact things. I was quite a theatrical kid and had an imaginative interior world. I would kind of act out scenes on my own. I like that thing of performing and presentation of yourself. It was later on that it became a critical methodology. It was really then I actually started to think “what does it mean that it is me.” When does it become a very specific decision that I’m placed within the work?

There’s an embodied experience of me being posited into a situation and the knowledge that is then acquired that’s still important. There’s this whole thing of othering or consuming of black bodies, but I think when I’m in those situations I feel more in control particularly when it’s white liberal audiences because I think I’m aware of the potential for creating awkwardness. It a kind of a power dynamic. I really thrive on live performances where there’s an unpredictability and randomness of things and you never really know how it will turn out. That creates this uncertain shared experience and that for me is very important.

In a lot of your work, you prioritize identity and the inherent politics it comes with. Often times when there’s a figure or any signs of the figure in the work, especially for POC folks, the work is often reduced to being about their identity. How do you think through this?

That’s a great question. I find that people often talk about it or don’t talk about it. And in a way, both seem weird. I’m really interested in subjectivity and identity, but the work also plays through other things. It is always an issue and it’s something that I come back to all the time. I think I’ve just gotten better at calling it out. It puts you in a situation of almost disenfranchising yourself. It’s like they are trying to fix the work. And for me, it’s become important to just call that out. Using platforms that allow you to state the discourse of your work either through artist and curatorial statements and being mindful of how institutions frame your work. I think it’s harder for artists of colour whose notions of identity are not of interest to them., they have to call that out [even more]. One of my favourite Black British artists Sonya Boyce talks about how we have talked about the work and what that is doing, and not the identity of the artist. Unfortunately, the burden is still on people of colour to call that out.

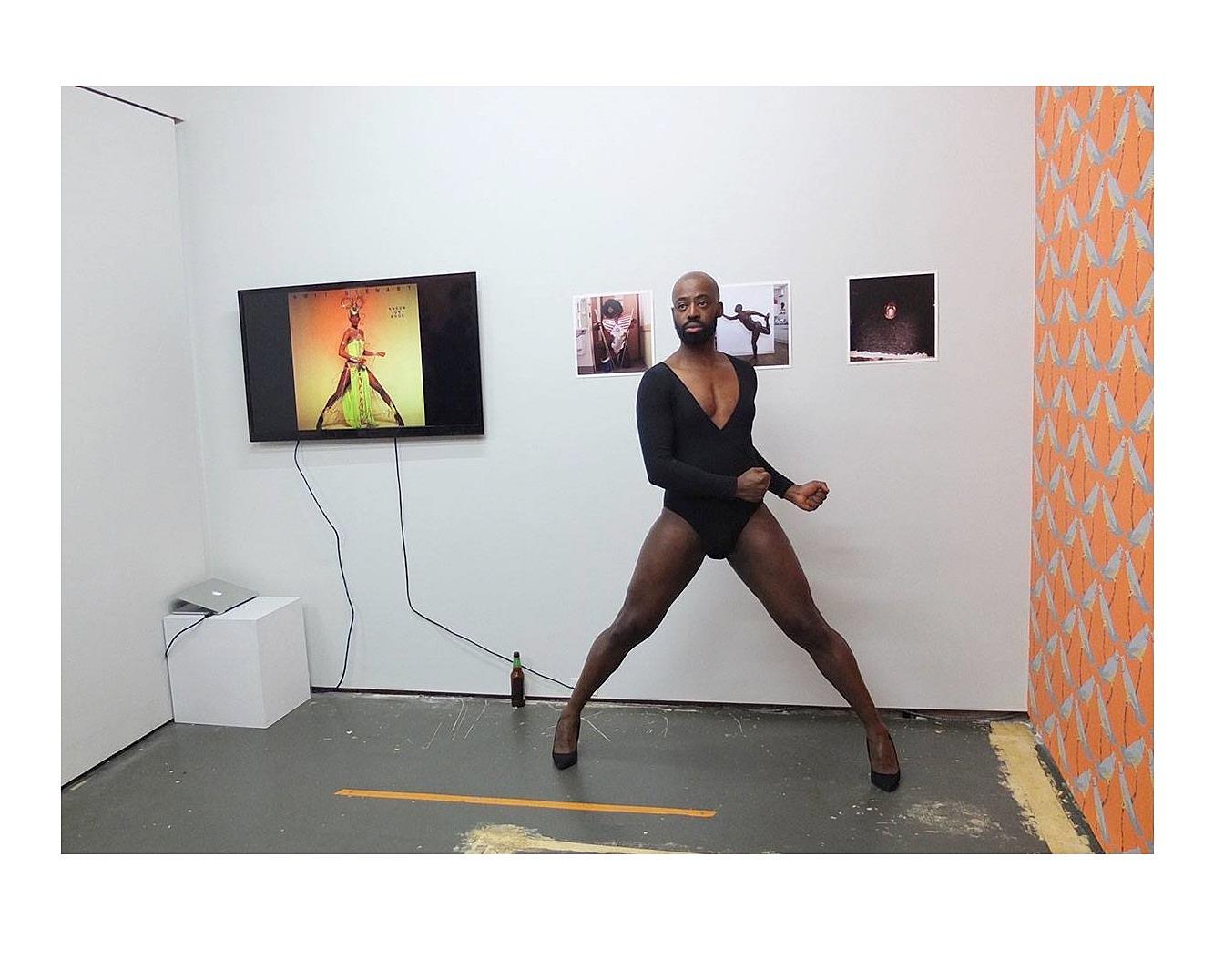

Another thing that reoccurs in your work is the use of drag, which seems to be a generative space for you

For me, there’s a real dissonance in using drag. It’s become a forum for thinking about gender identity. I think about what I do as a full drag or half drag or quarter drag. What I’m really interested in is as a cultural practice, so drag is always about the mimicry or the taking on or the assumption or the inhabiting of the cultural construct of gender. You’re never a real woman. You are embodying cultural constructs of what a woman is. Drag makes visible the problems of inhabiting misogynistic and patriarchal tropes. In particular [with] male to female drag, it’s important for me to think about what I’m afforded to do as a man being able to inhabit this trope of femininity in a way that people who identify as women are not able to. It’s become a critical device to think through the performance of identity. In encountering audiences it’s often disarming because I think they have an idea of how it’s received and how they might fix it because it exists in the context of entertainment. For me, it allows me to undermine some of those things and slightly subvert some of those expectations.

Reading the Realness, 2017

I’ll just end off by asking one last question about your most recent work, (I think it’s your most recent?) Reading the Realness.

Oh yes, it uses a source dialogue for the daytime talk show The Real, are you a fan of that show?

Laughs

I’ve seen bits of the show online and I do like the way they carry themselves and the conversations they have on that show. I also like the title of this piece and what you did with the interview they had with Rachel

I’ve just been obsessed with these female panel talk shows. I’ve been watching The View ever since Whoopi joined. And I’ve been watching the other ones like The Talk. There’s a lame one in the UK called Loose Women. I like the structure of these panels in terms of feminine discourse and the weird ways they juxtapose topics from politics to celebrity gossip to like, the death penalty. I had been reading a lot of writing in response to Rachel Dolezal’s outing. I’m always interested in how subjectivity is framed or constructed through the media. I was thinking about her being transracial which is something the media put on her. That conversation between her and the women seemed to distill so much. And the fact that it’s called The Real, I’ve been thinking about queer lexicons and this notion of “the real” and how that feeds into a wider vernacular. For me, it’s part of a wider project. There are these weird subject positions that are going on in that clip. That whole show is about women of colour, authenticity, pure, and truthful opinions. And you have Rachel, who tries to occupy the space but the way she frames it is through discourse. If you look at the way her conversation goes, it’s like a paper. She uses her qualifications; she’s like “you know, I went to Howard University,’ her position in the NAACP and those things become a conflict when Tamar Braxton says: “you can never live the experience that I’ve lived”. They talked about Rachel on The View as well, and Whoopi offered a different view on that. In Whoopi’s view, because she’s been presenting as a black woman, that is it. I think Whoopi’s argument is that she’s had to take the rough with the smooth which is different than Tamar Braxton’s view.

For me, it’s really thinking about social media and digital media as being a leveling archive. I was just thinking about how one can add some academic skills to the social media archive. So transcribing this clip into text and thinking about it divorced [it] from the voices of the original women as this free-floating text, and thinking about how the act of reading allows one to embody these subject positions in a way Racheal is trying to do but in a kind of refusal. In the structure of reading, I’m asking all participants to occupy each of the six subject positions in turn. Ideally, there are six participants and everyone reads it six times. Each time, they take on a different role. And so, there’s a collective reading where you go from reading yourself to listening to it five times. I’m interested in what’s afforded by that collective reading. I think that’s a way of entering an archive. If you think about an exercise with documents, it’s to do close reading and analyses. It is a repetitious act of re-reading and picking at the nuances. The first reading is a bit awkward, so I make it a point that they are reading the text for the first time. On subsequent readings, they play with language, emphasis, and cadences. By the end, you really get the sense of drama and layers that come out. For me that work is important at the moment, to think about the construction of identity within the context of the internet, the social media age. Rachel and her proposition is deeply problematic, but there’s something endearingly naïve about her. She’s trying to project this sincerity and it’s a difficult thing for people to receive. I wonder if blackness is big enough to embrace that as it is socially or politically fixed.