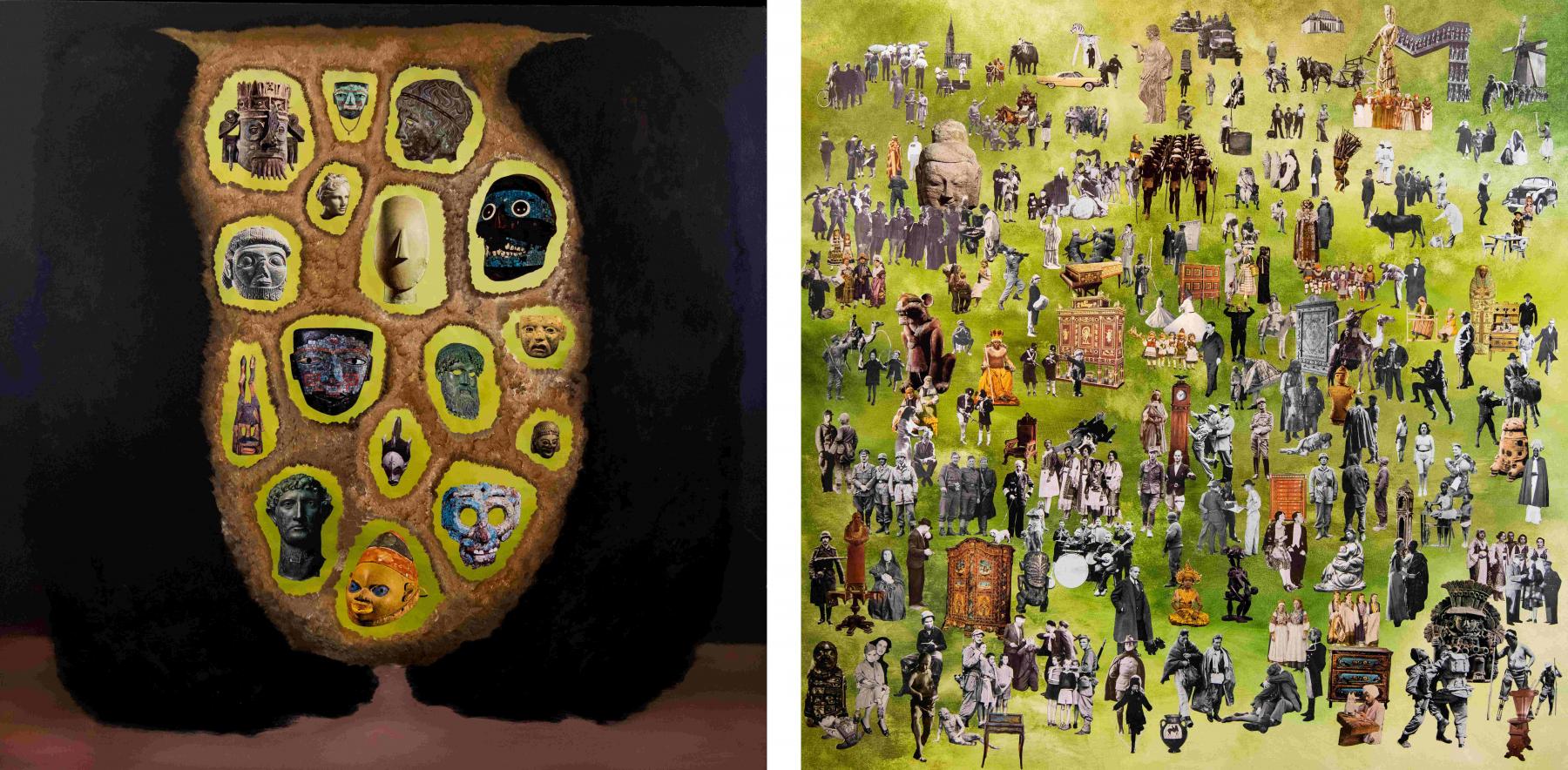

Joseph Tisiga, Mythic dysmorphic (bladder head), 2022, Expanding foam, wood, leather, shoe lace, marker, epoxy clay, synthetic wig, construction adhesive, 60.96 x 38.10 x 25.40 cm. (24 x 15 x 10 in.). Courtesy the artist and Bradley Ertaskiran

When I arrive at Joseph Tisiga’s home in Anjou, a neighbourhood in Montreal’s far East End, he is outside smoking a cigarette and scrolling through his phone. “The world news is hitting a higher octave these days,” he says in greeting, his dark brown eyes widening as he takes another drag. There’s a weariness in his voice that hints at a deeper exhaustion. Perhaps its the weight of a mind continually processing the world in complex ways. Or simply the strain of parenting a young toddler.

Conversations with the Kaska Dena artist tend to mirror the tone of his work: ruminative, at times brutally honest, always grappling with society’s fractures, its truths and its untruths. Though he enjoys long stretches of solitude in which he can let his mind wander (he used to take dishwashing jobs in Winnipeg and Vancouver simply so he could think through entire shifts), he is also a big talker. “I always joke that you almost need a seatbelt for your brain when you’re chatting with Joseph, because you’re on a ride and it’s going fast,” observes Mario Villeneuve, a longtime friend of Tisiga’s, over the phone from Whitehorse. “He has such a broad interest in everything. We’ve had many nights of rambling conversations, puddle-jumping from one thing to the other,” he adds.

Yet even when tackling heavy subjects, the artist approaches them with his quirky sense of humour, which is an integral part of his work. It is both funny and deadly serious—an anguished comedy. “I think that’s my secret skill,” Tisiga confides, laughing, during one of our conversations. “I’m like a stand-up comedian who doesn’t stand up.” Humour is a key motivator for him, not only as a source of inspiration but also a way of making storytelling relatable. “Trying to take the whole premise or context of a story and show it in one image is really hard. You have to couch it in all this other stuff,” he tells me.

Our first meeting takes place shortly after the spring equinox on a frigid but sunny afternoon back in 2024. The glistening snow is like layers of icing. The apartment blocks on Tisiga’s street all look the same: unassuming 1960s duplexes with angled garages, typical of residential developments at the time. We head inside to his basement studio and settle into two camping chairs. Marie-Pier, Tisiga’s partner, and their toddler, Nora Lou, are moving about on the floor above. We are soon joined by Phil, his scruffy little mutt, who tumbles down the stairs before settling at the artist’s feet.

Split between the basement and the adjacent garage, where Tisiga has set up a home gym, the studio has a retro vibe. Faux wood panelling lines the walls. The floor is carpeted with pieces of green artificial turf—the same kind that appears in the artist’s aphorisms series, with text rendered in plaster cigarette butts; and in his large-scale installation An Exercise in Resilience, acquired by the National Gallery of Canada in 2017. The tables are cluttered with cut drawings for new collages and some blank canvases lean against the walls. As I try to roll a cart out of the way, Tisiga reaches over to help. “It’s full of old rabbit skin glue,” he laughs, apologizing for the stink. He’s been using it as a binding agent in recent works. “It smells like rotting corpse,” he jokes.

Untitled, 2020, Installation of 25 individual works, plaster, watercolour and synthetic turf over wood panels 61 x 61 cm (each). Courtesy the artist and Bradley Ertaskiran

Tisiga, who turned forty last November, is known for his watercolours, oil paintings, collages, sculptures, and installations, though his earlier work also included performance and photography. A wide range of repurposed materials, both natural and synthetic, take their place in his art: wood, floor-waxer pads, animal fur and claws, porcupine caribou hide, construction supplies, tent fabric, architectural plans, and more. According to the artist’s mother, Sally Tisiga, this inclination for recycled materials stems in part from his modest upbringing. In a phone conversation, she reflects on raising two sons as a single parent on limited means. One of the best things to happen to her sons, she suggests, was growing up with little and having to rely instead on imagination and play. “I think that’s the most important thing to say in terms of how Joseph was or how he would later be able to make something out of nothing,” she shares.

Born in Edmonton in 1984, Tisiga spent his childhood moving between that city; Chilliwack, British Columbia, where his mother found work in the military; and Whitehorse, Yukon—the place of origin of his maternal family and his home base before moving to Montreal. His parents met in the military but separated when he was just two years old, so he and his brother alternated homes each year until he was thirteen. He was a curious child and full of character, his mother says. “Friends of mine thought he’d become a lawyer because he couldn’t stop talking.” She laughs as she recalls signing him up for a two-week art camp at age ten. “He protested and said: ‘You can’t do that. You’re not the boss of me! You can’t make me do art.’ And he came out with this incredible stuff from this art camp.”

In his teenage years, Tisiga entertained the idea of becoming a writer. He spent hours reading and writing stories and plays. His mother recalls how he would return from the library carrying bagfuls of books and often tucked pocket-sized books into his jeans. “I was reading a lot of political stuff like Noam Chomsky, Naomi Klein, and old plays like George Bernard Shaw,” he says. He also favoured dystopian classics such as 1984 and Brave New World.

With the new millennium, Tisiga found himself grappling with an early existential crisis and a growing awareness of class and racial injustices. There was a moment, he says, when everything about life suddenly seemed staged. At sixteen and living in Winnipeg, he was struck by the massive trees lining his street, by their “perfect” alignment, only later realizing they had been planted that way. “The city wasn’t built around the tree, the tree was built around the city. The tree is an object in a play and I’m a character, just like everyone else. We’re all puppets. But nobody is telling me what to do. I can do anything,” he says. “Anybody can do anything.”

Joseph Tisiga, Dream Catcher, 2020

Tent material and pastel 457 x 488 cm (180 x 192 in). Courtesy the artist and Bradley Ertaskiran.

Around that time, Tisiga dropped out of high school and moved into an apartment with a friend who shared his passion for skateboarding. “School was not my priority. I was a really bad student. I was failing all the time. But then,” he adds, “there’s this other part where I was super-engaged, but didn’t realize it.” His roommate at the time was studying art at the University of Manitoba and Tisiga would occasionally help him with small projects. He began to pick up on what his roommate was doing. “I think he planted a seed that I could make stuff too, you know?”

Broke as dirt one Christmas, Tisiga took his artist friend’s suggestion to make a painting as a gift for his mom. He made a portrait of her on a piece of cardboard, depicting her with the body of a cat, and his brother as a bird perched on her back. He then affixed it to an old window frame and sent it off. “It was hilarious in hindsight,” he chuckles. Although it was just a simple gift, he approached the task seriously and it instilled in him the idea that he might actually enjoy painting.

Tisiga’s first art show was a DIY outdoor exhibit that he organized in his early twenties while living in Crest, France. He had gone there to visit some family friends for a month, but ended up staying over a year. “Sometimes I’d travel and hitchhike,” Tisiga recalls. “But in my downtime, I was just there. That’s where I started painting.” The show featured “semi-abstract, semi-pop” paintings, loosely referencing what he thought was First Nations iconography. All the works were made with found house paint on thrifted bed sheets. He smiles at the memory. “People came and they were stoked. Some bought my work and it helped me live there a little bit longer.”

In Crest, he found a community of creatives—performance artists, sculptors, filmmakers, poets. But, inasmuch as he participated in their artistic demonstrations, he nonetheless felt like an outsider. “They had such awesome energy, but I couldn’t connect. It wasn’t my politics or my home.” It made him want to go back to Whitehorse and get involved in his own community. Upon his return, he founded a gardening society called Consider It Growing and later worked full-time at a community support NGO assisting people with disabilities. After that, he started managing the youth shelter at the Skookum Jim Friendship Centre, a non-profit organization dedicated to supporting the spiritual, emotional, mental and physical well-being of First Nations peoples.

Artist and curator Villeneuve and his partner, writer Heather Leduc, met Tisiga in Whitehorse nearly twenty years ago. He was still a “little Yukon kid” in his early tweens, starting out as an artist. Villeneuve had a studio tucked away in a back alley off Main Street, which he and Leduc turned into a small artist-run gallery called Studio 204. “One day, we see this young guy we knew from the coffee shop cupping his hands against the big window,” Villeneuve recalls. Tisiga walked in, introduced himself, and showed them his doodles of monster-like characters. “When we sat down with his drawings, we thought, wow, this is wild. This guy had quite an imagination. It’s very different work.” They decided to help him put together a portfolio and give him a platform. “He did a few shows in our studio. We had one with drawings just pinned to the wall and another where he made a giant teepee out of found objects that was way too big for the space,” Villeneuve laughs. “Most people in his life have a very warm spot for him in their heart.”

Attending one of those modest Studio 204 exhibitions was curator Mary Bradshaw, the Director of Visual Arts at the Yukon Arts Centre. Bradshaw later invited Tisiga to exhibit in the centre’s alcove gallery, after a last-minute cancellation. “I thought this was insane, though, because three or four months beforehand I was doodling with pens at work,” he reflects. “But I was like, okay, I’ll do it! And I took it really seriously and got some fancy paper.” Titled Indigenous Incisions, the exhibition featured a series of watercolours and collages with Curious George cut-outs and reproductions of works by Picasso. “It was an incredible show and people were so blown away,” Leduc recalls in a phone call. Everything sold out on the opening night, a sign of Tisiga’s strong support in the community.

Apart from a foundation year at NSCAD in 2011–12, Tisiga is self-taught. “Somehow, the universe cobbled together visibility for me,” he reflects. I first encountered his work at the Parisian Laundry in Montreal in 2017, the same year he received the REVEAL Indigenous Art Award. I remember being fascinated by the banal yet surreal scenes in his watercolours and trying to unravel the sense of emptiness and detachment in the figures he depicted. They seemed both human and ghostly, present and absent, familiar yet utterly foreign.

I meet Megan Bradley, co-director of the commercial gallery Bradley Ertaskiran and Tisiga’s gallerist, over coffee one afternoon. I ask her about the complexity in his work, the broad range of references, and how she introduces his practice to people unfamiliar with it. “Inevitably, people—myself included—want to be able to summarize an artist or practice so concisely that it often becomes reductive,” she reflects. “The hard thing is to make sure that people get to a point where the work can be about a lot of things together.” Bradley observes, for example, that even though Tisiga is largely self-taught, “he’s very aware of art history, he’s referencing and engaging with that a lot, sometimes critiquing it, but mostly very interested in it.”

Tisiga and I meet again a couple of months after our first studio visit, this time on a hot, humid late-spring day. We sit in the back of Grumpy’s, a downtown Montreal bar, over a couple of IPAs. The space is loud and dark, but cooler than the heat outside. As I try to pick up the conversation where we left off, I’m drawn back to his early sociopolitical awareness and the question of who or what might have shaped it.

Although Tisiga credits the punk and hardcore scenes that attracted him as a young skateboarder, he emphasizes the influence of his home environment, particularly his mother and her commitment to social justice activism. He remembers her taking him and his brother to Mondragon, a political bookstore and vegan café in Winnipeg, as well as other community events where survivors of residential schools and the Sixties Scoop shared their stories. “She was really into providing us with this early, firsthand exposure,” he says. Sally Tisiga agrees, telling me over the phone that she often made a point of discussing “adult issues” at the dinner table, even when her sons, being teenagers, weren’t so interested. “I’d just keep talking,” she says. “I didn’t know what they’d hear, what they’d remember, or if it was important to them. And then we worked on a documentary as a family, and that expanded things for him.”

A member of the Kaska Dena Nation, Sally Tisiga is herself a survivor of the Sixties Scoop. She was removed from her family at age four and placed in foster care. Born in Lower Post, in northern British Columbia, near the Yukon border, on the homelands of the Kaska Dena, she lived with five different families across four provinces and one territory. Her story is documented in the film One of Many (2004), which follows her and her sons as they travel to Yukon in search of fragments from her past. In the film, Sally reflects on the shame, loss of identity, and cultural disconnection that continue to haunt her—themes also central to her son’s work. After some time in the military, she worked in social services in Whitehorse and Vancouver, and later in Winnipeg, where she led a program to help Sixties Scoop survivors reconnect with their families.

It wasn’t until the late 1990s and 2000s that Tisiga began to learn about his mother’s experiences and the impacts of Canadian policies like the residential school system and the Sixties Scoop. He confesses that as a teenager, he even questioned whether she was making up these stories, as the topic was so rarely discussed or included in school curricula. When he realized that his family’s history had been deliberately excluded from the textbooks, it confirmed his feeling that school was just a form of conditioning.

At the bar, our conversation shifts to his latest solo exhibition at Bradley Ertaskiran, It Was God the Whole Time, in early 2024. He made ten large paintings for the show, which he conceived as a single narrative: they wrap around the gallery’s bunker space and unfold like still images along a reel of film. When an idea comes to him, he explains, he usually visualizes it like a movie. These recent works contrast somewhat with his earlier watercolours and paintings, which he describes as “figurative scenarios” or “micro-performances” that condense multiple narratives into a single frame. “These new pieces have much less information individually,” Bradley explains. “His watercolours are so rich, with layers of activity on every surface, and these works are like blow-ups of just one small part. It’s really representative of the way Joseph thinks.”

Joseph Tisiga, It was God the whole time, 2024. Bradley Ertaskiran, Montreal, QC, CA.

Joseph Tisiga, It was God the whole time, 2024. Bradley Ertaskiran, Montreal, QC, CA

.

Joseph Tisiga, It was God the whole time, 2024. Bradley Ertaskiran, Montreal, QC, CA.

Under the dim lights of Grumpy’s, I flip through a stack of images of Tisiga’s paintings that I printed and brought with me. This new body of work continues his long-time examination of the ongoing effects of colonization on Indigenous lives: lack of access to traditional lands, knowledge, and practices; food scarcity; conflicts related to resource extraction; and persistent stereotypes surrounding Indigenous identities.

As in much of his work, Tisiga interweaves Western cultural symbols and allegories with traditional Kaska Dena stories, such as the legend of Dzǭhdié (also referred to as “the bladder head boy”) and the Giant Worm, which he’s interpreted a few times. Rather than treating these as traditional retellings of Kaska Dena legends, he uses them as a lens to interpret the present.

“With the Giant Worm story, I thought, oh, this is really like mining. He’s [the worm] subterranean, digging out the ground underneath and then attacking the people up on top, killing them or maiming them,” he describes. For Tisiga, it’s about creating space for these stories, “especially for Kaska and Dene people,” he specifies. “It’s about representation, an extrapolation of these historic ideas. Maybe someone sees the story as I’ve represented it, recognizes it, and then interprets it in their own way. It leaves a trail to respond to.”

Tisiga’s mother recalls one anthology of Kaska stories that left a mark on him. There was also a family friend, a traditional Kaska storyteller, who would repeatedly tell her boys the same story, the one about a girl who goes berry picking and meets the bear people. “When he started really getting into the stories on his own, when he was about 19 or 20, and started exploring their meaning, I think something different happened.” She adds: “Let’s see if I can try and find the words to describe it. This is connected to something that I sometimes don't even think he’s aware of and it’s something really old. It’s like this voice. When I look at his work, I see the old voices from our family, our unknown family. He seems to be a receiver of questions, of ideas, of things. But at his core, the soul of him, from my perspective, is that old voice coming through.”

In one of the recent paintings, a shadow in the streets (2024), a figure in a headdress is riding a horse down a street bathed in deep browns and purples. The “noble savage” on horseback is a ubiquitous image in the North American perception of First Nations or Native American people. “I imagined it ripping down the street in a moment preceding this kind of violence or conflict. Or maybe it’s just a moment of freedom.” Behind the figure, in the painting’s background, we see apartment buildings reminiscent of those on Tisiga’s street.

Another work, Scarcity in the modern world should appear absurd (2024), shows a pond filled with sockeye salmon, with someone’s legs submerged in it and a red stick of dynamite about to detonate. “The dude’s got his legs in the pond and he’s gonna blow it up, blow his own legs off,” Tisiga laughs as he shares this. “That’s classic Mad magazine humour.” Beneath the slapstick humour, though, is a reference to salmon depletion in the Yukon due to overfishing. In the past decade, dwindling populations have led to fishing restrictions and food scarcity, not to mention the weakening of traditional practices associated with it.

Joseph Tisiga, Paralysis is an Abject Experience, 2020. Watercolour on paper 70 x 70 cm (27.5 x 27.5 in.). Courtesy the artist and Bradley Ertaskiran

He finishes his beer before I do and heads off to grab another. “I like tying it on a little bit. It’s good for thinking,” he chuckles. “You spend so much time in your own head, sometimes it’s good to get a little drunk and be like, what do I think about all this other stuff I never think about?”

I ask Tisiga what’s next for him. He tells me he’s considering giving school another shot, maybe pursuing an MFA. These past two years, he’s spent a lot of his time caring for his daughter, marveling at her growth. “Seeing what babies do when they grow, it’s fascinating,” he says. “It’s this constant progression, like evolution unfolding before your eyes.” He wants to dedicate more space in his practice to other forms of making, such as sculpture, ceramics, and crochet, which he first learned while hitchhiking with a friend around Canada at 18. “I love repetitive tasks that don’t require much thinking. I can just do the same thing over and over, almost like a mantra. Sometimes, I’ll build an entire project around that repetitive act.” The painted bricks, small houses, stick figures, and the plaster cigarette butts fall into this category.

Though he sometimes steps away from making new work for long stretches, Tisiga’s mind is always at work. Once an idea takes hold, it inevitably evolves into a future project. “A big motivator for me is knowing that if anyone’s going to speak for me, I want it to be me. And art is the vehicle, you know?” Wherever that voice is from—whether it’s his own or that of his ancestors—he’s committed to letting it come through.