Elizabeth Peyton, Twilight, 2009, oil on panel, 8.5 x 11 inches

We grew up with our tongues pressed so hard against our cheeks, it’s no wonder we all needed braces. That’s a title for one of my own paintings: a couple kissing against a violently green background. I used the kiss between Drew Barrymore and her costar in the 90s film Never Been Kissed as a reference but it really could be any B-movie kiss, and that’s the point.

A writer whom I admire, and frankly have a bit of a crush on, lent me a monograph about the painter Elizabeth Peyton. A review by Roberta Smith contextualized Peyton’s cringingly sincere, fan girlish portraits of the recently deceased Kurt Cobain, invoking Realism, Karen Killimnick, and the Pre-Raphaelites. She diagnosed the portraits as part of a 90s trend toward “emotionalism,” an excellent description that never really stuck. I’ve been thinking about this review a lot. And I haven’t returned the monograph.

1—Most basically, Emotionalism is a genre of art: paintings, photography, film, and literature, etc….

2—Emotionalism is sticky, tinted pinkish red. It attracts wasps.

3—Emotionalist works all share a mood; a frank sentimentality.

Elizabeth Peyton started showing in New York in the 90s, when figurative painting was having a renaissance. Among her peers were John Currin, Lisa Yuskavage, Sean Landers, and Richard Phillips, but there seemed to be one major difference: where Currin, Yuskavage, Landers, and Phillips’ paintings were interpreted as ironic jokes (for the most part correctly), Peyton’s small jewel-like portraits of celebrities (the crushable kind) and historical figures (the French kind) struck audiences as sincere.

It was around this time that postmodernism is considered to have ended; old forms, like figurative painting, were being reanimated to serve new content and cynicism wasn’t feeling as smart as it used to. In 1993 David Foster Wallace implored fiction writers—via essay—to abandon their ironic disinterestedness and embrace sincerity. His call to disarm may have worked. New Sincerity, a movement in art, literature, film, and music with roots in the 1970s, gained new followers and practitioners. Whether this is because of Wallace or just an inevitable cultural trend is hard to say.

Despite all this, irony and cynicism continue to be cultural mainstays. Wallace attributed irony’s ubiquity to television. Lauren Michele Jackson, in a 2025 editorial for The New Yorker, followed up on Wallace’s proposition, suggesting that the social internet, the next big thing after TV, propelled irony even further: “[A] posture of unseriousness pervades institutional and individual channels alike.”

Emotionalism is neither sincere, nor cynical. Or maybe more accurately, it’s both. Emotionalism is naive with a wink, its idealism is pragmatic, critique’s pill is ensconced in a jawbreaker’s sugar.

Emotionalism is embarrassing. It can embarrass its audience (oh god, I can’t believe I like this) or its author (oh god, I can’t believe I made this). Emotionalism definitionally reveals something private.

4—Emotionalism is concerned with simulacrum; there’s a reiterative quality, a trying-to-get-the-feeling-rightness. It shares this with Romanticism alongside themes of beauty, nature, the individual, and romantic love.

I was in New York earlier this year where I saw the Caspar David Friedrich show at the Met. Dark rooms were thronged with whispering visitors who wove politely around each other, all trying to get a good look at Friedrich’s beautiful and impossibly cinematic tableaus of Gothic ruins backlit by sunsets, and individuals posed heroically in windswept landscapes. Friedrich’s work, once dismissed for its distasteful admirers—first Adolf Hitler (for obvious reasons) and then Walt Disney (too schmaltzy)—has had a resurgence as part of a larger cultural trend towards Romanticism.

The Romantic genre covers a lot of conceptual ground: life and death, collectivism and individualism, beauty and ugliness. It is this oscillation between polarities that makes Romanticism the ideal genre for our contemporary moment—one of simultaneous “irony and sincerity, hope and despair, empathy and apathy” write Timotheus Velmeulen and Robin van den Akker in their paper, “Notes on Metamodernism.”

Emotionalism, though, is much smaller in scope than Romanticism. It’s more like Realism in this regard, wanting to capture life in all its granularities.

5—If Caspar David Friedrich was painting about losing his virginity I think he’d be an Emotionalist painter.

6—A non-exhaustive list of Emotionalist works and practitioners:

Elizabeth Peyton.

Claire Millbrath.

Lois Dodd.

Fairfield Porter.

Boris Torres.

Stand by Me, by the late great Rob Reiner.

Cindy Hill’s bronze diaries.

Nadya Isabella.

The portrait of Hari Nef by TM Davy

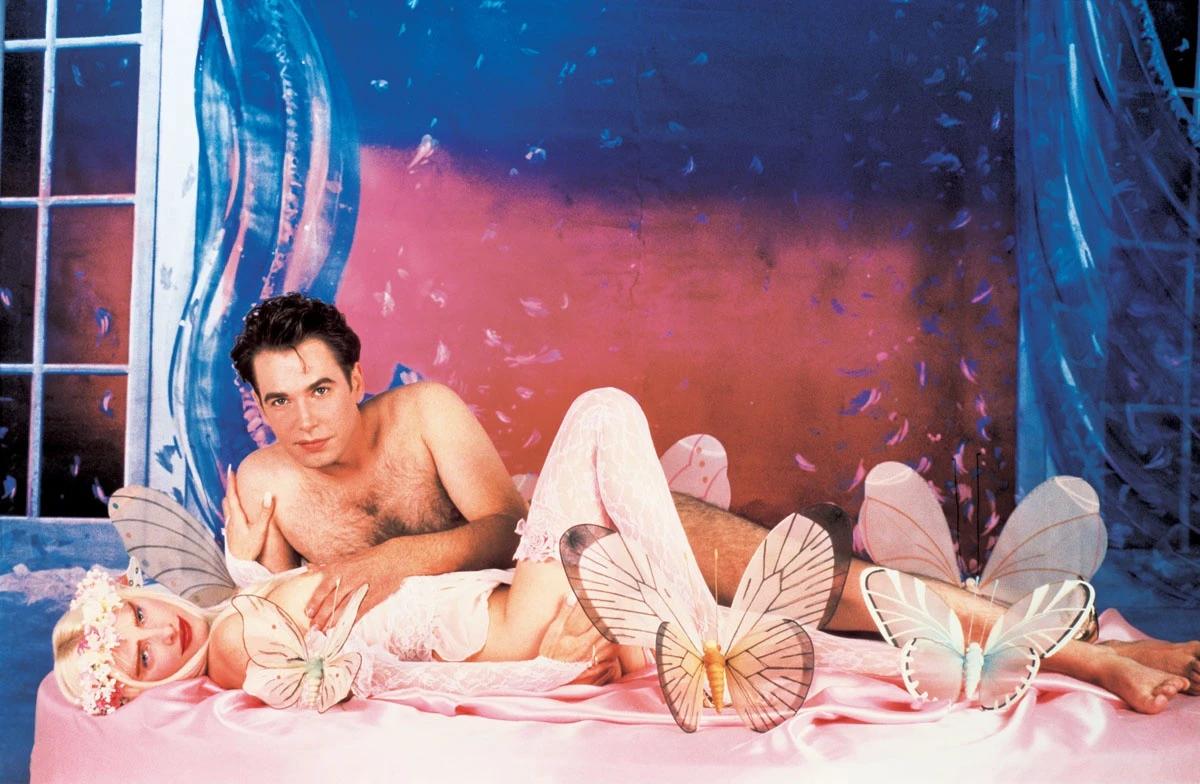

Jeff Koons’ Made in Heaven, where he’s having sex with his soon to be wife, Ilona Staller.

Wolfgang Tillman’s more diaristic photos.

Karen Killimnick.

Frank Ocean’s music, especially his song “Siegfried”.

Dike Blair.

Joy Williams’ short stories.

Claire Milbrath, Dog in Pansies, 2024, Acrylic on canvas, 22 x 28 inches

Jeff Koons, Hand on Breast, 1990, oil ink silkscreen on canvas, 97 x 143

7—Emotionalism’s origins are older than the 1990s. Postmodernism’s cool had to have a foil. Artists like Lois Dodd and Fairfield Porter, unconcerned with Pop art and Minimalism, painted bucolic landscapes and rural domestic scenes while their peers made tongue-in-cheek celebrity portraits and inaccessible navel-gazing obelisks.

8—A friend of mine once said, with a big grin on his face, “making art is humiliating” (at the time, he was making work about gay abjection using the metaphor of pissing his pants). Obviously I agreed with him but I don’t think this is true for all artists. I don’t think the Abex guys felt humiliated by their work.

Amy Sillman writes “...what could be less punk than staying up late in a studio trying hard to make a ‘better’ oil painting? That’s so earnest, so caring…” In grad school I told a room full of my peers and advisors that I wasn’t trying to make good paintings. I meant academically good—I wanted, and still want, to paint with an awkward and amateurish approach to my subject matter, to imbue the picture with vulnerability.

Emotionalism is embarrassing. It can embarrass its audience (oh god, I can’t believe I like this) or its author (oh god, I can’t believe I made this). Emotionalism definitionally reveals something private.

Critically though, Emotionalism is not about shame. Shame is too biblical. Emotionalism courts the blushing cheeks, downcast eyes, and nervous laughter of embarrassment. Embarrassment is quotidian and lower case “h” human.

9—Emotionalism isn’t about sex. Except sometimes it totally is.

10—Emotionalism and Camp overlap a lot. While rereading Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” I realized that Camp foretells the prevailing contemporary attitude that Velmeulen and van den Akker would diagnose half a century later. Sontag talks about a “sweet cynicism” and a play with naiveté in her descriptions of Camp. Importantly though, Camp is a sensibility, a taste you develop, something which exists in its purest form when it’s accidental.

Emotionalist works of art can be mischaracterized as tacky or nostalgic and get lumped in with Camp. Emotionalism, though, is not a miscellaneous kitten calendar, or the portraits of A-listers by the late Palm Beach resident and neo-romantic painter Ralph Wolfe Cowan; those things are Camp, which is a term that can be (and often is) applied retrospectively. Emotionalism is a genre that artists work within.

Mona Hatoum, Van Gogh’s Back, 1995, chromogenic colour print, 19 1/2 x 15 inches.

11—Emotionalism is feminine–not to say that it can only be practiced by women, but more that it is wistful, silly, pastel, and frivolous. It loves love and sunlit interiors and days at the beach with a picnic. These things aren’t inherently feminine, it’s more that the quotidian and sentimental have become associated with the feminine. I think it’s because of this that many of the artists I include in this genre are women and queer people.

When American critic Joseph R. Wolin wrote an essay on Ann Craven for Border Crossings magazine he described her work as brightly hued, kitschy, anodyne, suitable for postcards, clichéd, but never the most obvious: feminine.

12—Romanticism’s great flaw is its ability to be co-opted. I think again of Caspar David Friedrich and his work’s appeal to a Fascist Germany. Friedrich’s paintings of a solitary figure overlooking a landscape were easy to parlay into emblems for German nationalism. (Ralph Wolfe Cowan painted Donald Trump’s portrait in 1989.) Emotionalism on the other hand is too ordinary, too girly, too gay, and too stupid to appeal to the political right.

13—William J. Simmons writes in “Queer Formalism: The Return,” “…for in queerness or queer formalism we might understand and find liberation in the facts that everything has been done before and there is no such thing as greatness, which is not to say that nobody and nothing can be truly special, but rather that all moments, all experiences, all of our daily intimacies and disappointments coalesce like paint or photographic chemicals into the image of a life, and that is good enough.”

Though Simmons was writing to define his own category, Queer Formalism, these sentences also gesture to the heart of Emotionalism: the sanctity of the quotidian and a sincere admiration of cliché. Simmons gives us permission to do it all anyway, despite the cliché, because nothing is original and therefore everything is valid. There are no heroic figures in Emotionalism.

14—Mona Hatoum’s photograph, Van Gogh’s Back (1995), is a perfect example of an Emotionalist work. It’s critical and funny and sincere all at once: the photograph’s tight crop shows only a man’s back, slick with water and soap. His dark back hair is combed into swirling circles. Hatoum’s wonderfully corny title turns the man’s back into the starry night. It reminds me that the private world shared by two people can feel as expansive and complicated as the Milky Way, that god exists in all of us, and that the personal and the political are always intermingled.

15—Emotionalism thinks, well there’s a reason it’s cliché.