Lauren and family visiting Nose Hill Park, 2019. Photo by Evan Peacock.

Lauren Crazybull and I met in the fall of 2019 on Treaty 7 territory while they were in the midst of gathering research as the province of Alberta’s first Artist in Residence. A year later, the research culminated in an exhibition, TSIMA KOHTOTSITAPIIHPA Where are you from? presented at Latitude 53 and subsequently at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery (SAAG). While working with Lauren on the SAAG iteration, I was struck by the depth of personal and historical experiences contained within Lauren’s exhibition. This multimedia project of audio, photographs, a book, and paintings culminated in an immensely thoughtful intersection of personal, cultural, geographic and linguistic Indigenous issues. Through discussions with Lauren, I felt that there was still so much about the travels, stories, and historical context of the exhibition that went unsaid.

Through conversation, we strove to bring out the details of Lauren’s experience travelling across Alberta, hearing the stories of the people, places, and histories that made TSIMA KOHTOTSITAPIIHPA possible. This project diverges from Lauren’s more widely known practice as a portrait painter. Lauren uses large-scale portraits to interrogate how Indigenous identities have been historically (mis)represented through visual culture. Throughout all of Lauren’s work there is the constant assertion of their own humanity and an avocation for the intellectual, spiritual, creative and political fortitude of Indigenous peoples.

Lauren and I began our conversation during an evolutionary period in their practice, moving from Alberta’s Artist in Residence to working and exhibiting in Edmonton/Amiskwacîwâskahikan and then to their first semester as a Masters of Fine Arts Candidate at Emily Carr University in fall 2021. Our discussion is framed by the people, places, and experiences from Lauren’s time as Artist in Residence. Lauren describes how physical and cultural displacement continues to impact Indigenous people in Treaty Six, Seven, and Eight territories and reflects on the pedagogy, variety, and precarity of Indigenous languages in those regions.

Based on Lauren’s lived experience, they outline how the spirit of the residential school project continues today through Canada’s foster care system. Finally, Lauren describes their love of skateboarding and how the recent move to Vancouver led to a reconsideration of the places and activities that they call home.

Every choice I make is a response or a way to get away from those images that keep Indigenous people in the past.

Adam Whitford: I was recently reminded of your earlier portraits from 2018 when two of them were acquired by the Alberta Foundation for the Arts. Four years doesn’t seem like a long time but your work seems to have changed a lot since then. How do you approach portraiture differently now compared to just a few years ago?

Lauren Crazybull: I think a lot has become clearer for me. I made decisions in terms of scale and color that weren't immediately evident to me in the beginning. As I kept painting, I realized that my practice was sort of a response to images that I grew up seeing of Indigenous people. Everything is always changing and evolving and so will my practice. I think the evolution of my portrait practice is more about learning about why I made certain decisions. It's also a practice of getting to know my community.

Your portraits are not just paintings of Indigenous people but they interrogate past stereotypes of Indigenous representation. Portraits from the past were often romanticised images of unnamed individuals, stuck in the past and clothed in inappropriate costume. Given your focus on contemporary portraiture, how have you set your work apart from previous histories of Indigenous portraits?

I think the constant framing of Indigenous art in relation to the past can relegate us to that time too. My work is different from artists like Nicolas de Grandmaison because I'm not a settler creating inaccurate romanticized images of Indigenous people. Every choice I make is a response or a way to get away from those images that keep Indigenous people in the past.

I’m interested in focusing on your time as Alberta’s Artist in Residence and the resulting project from that time, TSIMA KOHTOTSITAPIIHPA. Talking with you about the project over the course of its creation and presentation revealed that there was a deep entwining of political and personal history that was just not apparent looking at the work alone.

Thinking of your time as Alberta’s Artist in Residence, whether conscious or not, there is something decolonial and a bit rebellious about using the money and time awarded to you to reconnect with language, culture, and family that the same government had a hand in taking from you. Before you even began the project, what did you imagine doing with the resources and the platform afforded to you?

I think I was just really excited to have that time, the resources, and space to create something and think through it. It's such a privilege to be able to have time to create. I wanted to begin a project that I could continue to build on. Language learning, making familial connections, and pushing my work in a new direction is something that continues to be valuable to me. I'm grateful for the opportunity to connect with different communities and contribute a piece of art that shows an ongoing learning journey—one that has reclamation as its goal.

As you began your time as Alberta’s first Artist in Residence in 2019, you spent that year travelling across the province, doing personal research, and making work for the resulting exhibition. You were chosen for the residency during Alberta’s only New Democratic government but the provincial election during your residency brought the Conservative Party back. Did you feel that your position as Alberta’s Artist in Residence was politicized by either party?

Honestly, I wasn’t very interested in thinking about either party. The NDP started the program and when I applied, I really wanted to just focus on my project and stay as far away from the government aspect of it as I could. When the election was called, the Alberta Artist in Residence social media was basically frozen because a lot of government accounts had to be paused during the election.

I did my best to avoid any sort of interaction with the government beyond what was required for the role. I just didn’t want to leave a lot of room to become a symbol of either party. I think that served me well, making sure I was distanced from that and focusing on my project.

You mean remaining a little bit apolitical or flying under the radar?

Yeah, because it’s easy as an Indigenous artist for people to use you as a symbol or as someone they tokenize. I’m not interested in that because I don’t think that ultimately it’s in my best interest.

Over the course of the year-long residency, you made at least eleven different trips to different parts of Alberta. What were you looking to find on those trips?

I just wanted to start with an open mind. The first trip I did was to Nose Hill Park in Calgary because I know that it’s a significant place for Blackfoot people. I took my siblings there and we saw the medicine wheel. It was a foggy day and it felt symbolic for that stage of the residency. Literally searching through the fog was how it started in the beginning. I was going to a bunch of places, not knowing what would happen, but trusting that maybe it will lead me somewhere.

I also ended up going to the archives at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary and I found a picture of my great grandfather, who was in residential school. Then I thought that I wanted to go all over Alberta, anywhere that was culturally significant. If you look at the map, you can see that there are mostly names for places in Southern Alberta, and I think that’s because I have more of a connection with that side of my family—my Blackfoot side. I lived down in Lethbridge for four years so it was easier for me to know what spots in Treaty Seven are important.

The initial plan was to go to each place and learn the name, but it opened up to more than that. When you talk to someone, they’ll inevitably be like, “talk to this person and this person.” I had a lot of trust in that sort of thing. I just followed what info I was given at each place and went with what felt best. Originally it was supposed to be more of an objective map of these places, but it became a lot more personal.

Lauren Crazybull, Kainai, digital photograph, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

When you talk about the names, you’re going to each place to find the original place names in Blackfoot, Cree, or Dene. Who did you meet that helped you find these names?

My aunt, Sandra Manyfeathers, she is a fluent Blackfoot speaker so she definitely helped me a lot. I ran into Glenna Cardinal and seth cardinal dodginghorse at the Glenbow and they showed me how to use the archives. Faye HeavyShield was a huge part of this. She took us to the Kainai reserve and we met her friend who knew my great aunt Stella Crazybull. Stella was a nurse in Kainai and was a big part of the community back when she was alive. It felt like Faye was welcoming me home in a lot of ways, which felt really nice.

I didn’t grow up there and it’s really hard to find a connection when you grew up away from your community. Meeting Faye and going to Kainai will always be an important part of my life outside of the residency.

We say that she’s the grandma of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery (SAAG). She’s great at making people feel welcomed.

And everyone at SAAG, talking to you, Brandon, and Kristy that was really nice. It meant a lot for that work to come to Lethbridge because it was so heavy with Treaty Seven content.

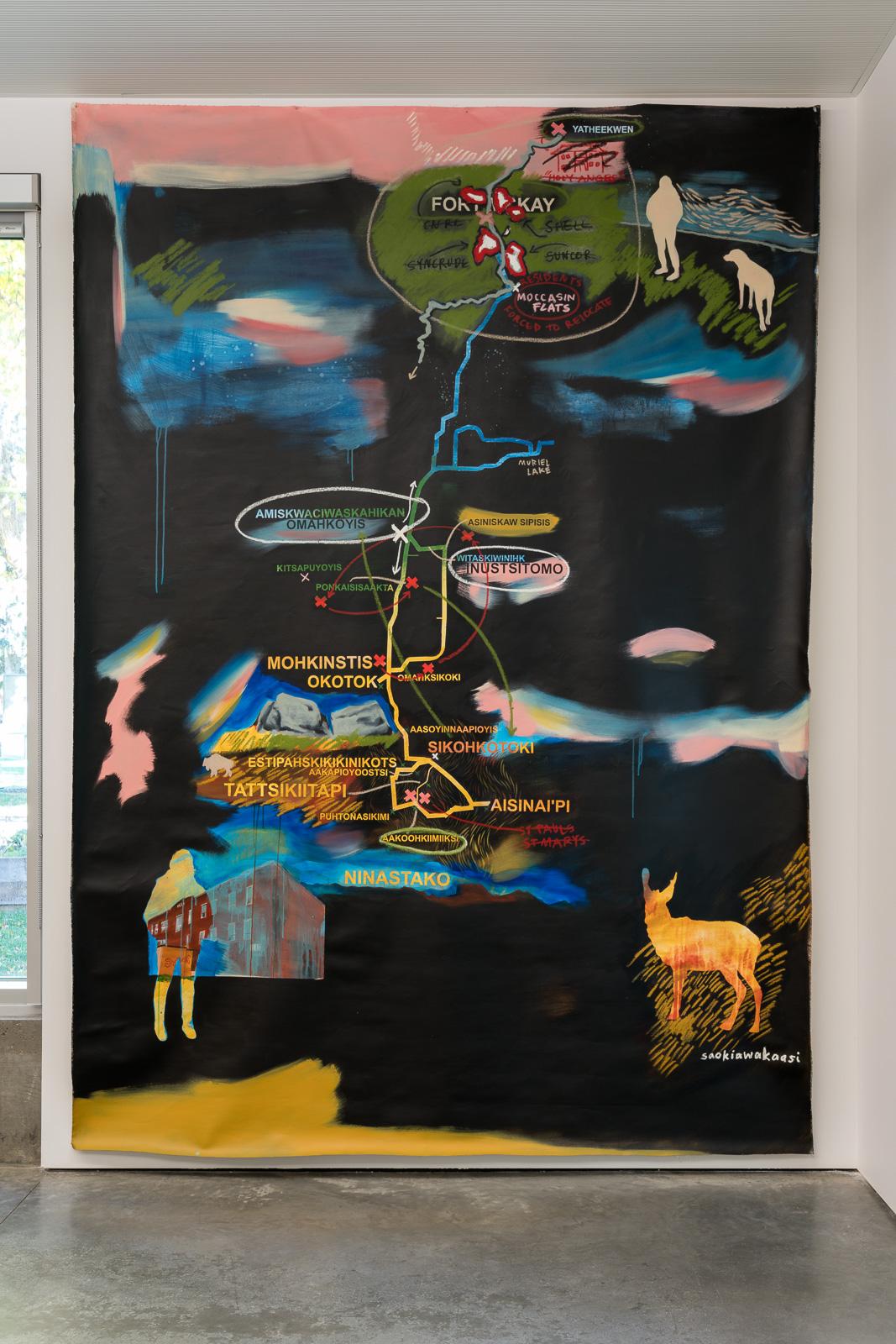

The major work to come out of your residency was a painted map of Alberta titled TSIMA KOHTOTSITAPIIHPA meaning “where are you from?” in Blackfoot. This was the centerpiece of the exhibitions at both Latitude 53 and the SAAG. With both exhibitions being titled after the painting, why was that phrase so important to the project as a whole?

The title is important because a lot of people are asked that question but it gets complicated for me because of the instruments of colonialism, like the child welfare system and residential schools. When people ask me “where are you from?” I don’t always know the answer. Growing up in foster care, I was raised all over rural Alberta: Camrose, Strathmore, Caroline, and Red Deer but I don’t consider those places to be my home. I haven’t returned to those places since living there.

My dad is from Fort McKay up north and my mom is from Kainai down south, so it was a question of “where am I from?” That was the driving question of the project.

You mentioned your time in the foster care system and in marking your personal history onto the map, there are two pink X’s in Southern Alberta that indicate the sites of St. Mary’s and St. Paul’s residential schools. These are painted in a similar way to the five red X’s marking the homes you lived in foster care. Given the over-representation of Indigenous children in the foster system—Indigenous children make up 7% of the youth population but account for 50% of the children in foster care—how is Canada’s foster system a continuation of the residential school system, or is it?

I definitely think it is. They are all tools of colonization that contribute to genocide in Canada. It’s just different forms of colonization. It’s the same sort of thing, kids being taken from their homes and placed where they don’t have access to their culture, losing important parts of who they are. I think that’s a very clear example of residential schools continuing in a different form.

As someone who went through the child welfare system, I’m really catching up. This project was a way to figure out my own connection to these places. People on both sides of my family went to residential schools, my mom went, but before that my grandma went, and my grandma on my dad’s side. You can see at the top of the map, another X and that’s Fort Chipewyan. That’s kind of why I have the pinkish X’s – it’s a faded version of the red that’s still fresh for me. It would have been different if I was in foster care in Lethbridge instead of rural Alberta, where my own family could have access to me. It’s hard to get out to Caroline, Alberta without a car.

Lauren Crazybull, TSIMA KOHTOTSITAPIIHPA, acrylic paint and oil paint stick on unstretched canvas, 2020. Photo by Blaine Campbell.

Lauren Crazybull, TSIMA KOHTOTSITAPIIHPA (detail), acrylic paint and oil paint stick on unstretched canvas, 2020. Photo by Blaine Campbell.

You’re still displaced a long ways away, being made inaccessible to your family’s history and knowledge, so that’s proof enough that the spirit of residential schools continues.

Within the painting, there are distinct clusters of places and names, in both Blackfoot and Cree and in Northern Alberta, some places are in one language or none at all, how did that come about?

Southern Alberta was a lot more accessible to me, there are just so many people willing to share knowledge of names and there are a lot of resources there. There’s even a few Blackfoot language apps where you can find the names of places, and there’s a lot of people who are fluent in Blackfoot like knowledge keepers and elders. That’s why there’s so much richness in the map there. But travelling up north to Fort McKay, it was different. Partly because it was my first visit as an adult there, I didn’t feel like I could just go there and start digging for answers. It didn’t feel right for that to be the only reason for the visit.

I think part of it is that in the northern areas, it’s a lot colder and with that, people have spent a lot of energy just trying to get through winters, so there was a lot less information available to identify those places. It’s not the same as Southern Alberta where there are preserved World Heritage sites like Writing-On-Stone and Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump.

In the northern part of the map you also have a location outside of Fort McKay called Moccasin Flats. You draw attention to it with text on the map saying that the residents were forced to relocate.

My grandma used to live in Moccasin Flats and as we were driving by, she told me that the Métis people who were living there were evicted and locked out of their homes to make way for more development of Fort McMurray. I included that because I think there is so much displacement that has happened in favour of more settlers being able to move into these spots. A big part of this map is showing that displacement happens. The displacement of the folks who lived in Moccasin Flats, the residential schools that I marked, or my own experience in foster care, being displaced from our homes is important to acknowledge. Displacement is another tool of colonization and everybody has a part in it.

When I think of a mental image of a map, what comes to mind is the map of Canada with grid lines, different coloured provinces, capital cities with stars, and major settlements that are clearly marked. It’s meant to feel timeless and objective. Instead, your map of Alberta marks the travels of one person, describes the passage of time, where you lived as an individual, and it feels assured about neglecting traditional landmarks. It also marks locations like residential schools that other maps would rather forget. How important was it for you to confront settler map conventions?

When I first had the idea of making a map, I knew it wouldn’t include any borders. I could have cut it out in the shape of Alberta but ultimately that doesn’t mean a whole lot when you think about the history of the land. Canada is just a small sliver of time in the history of the land we are on. I didn’t even want to have treaty borders; the land is just the land. Looking for original place names felt more true to the land and people’s relationship with it.

It’s interesting to me how people interact with the map. As people learn about original place names more, they’ll be able to say, “oh, this is Amiskwaciwâskahikan for Edmonton.” Reorienting people and having them see the land differently was important. I wanted people to be curious so if I had put the border there, it would have been easier for people to geographically place these spots.

People could start to teach themselves a little bit even if they have no familiarity with Blackfoot, Cree, or Dene. They could come away learning a word.

Totally.

The map is also a kind of psychogeographic document. Guy Debord describes this as the specific effects of the geographical environment on the emotions of individuals. One way of experiencing the psychogeography of a place was through the derivé, or exploring the streets to see how the city makes us feel. As you were travelling, did you find that the infrastructure of Alberta or the landscape had an emotional or psychological effect?

I think about how one of the places I wanted to visit was Ninaiistako (Chief Mountain) that is not as accessible because it’s in the States, but it’s also a Blackfoot landmark. From Waterton I could see the mountain, but the U.S./Canada border separated me from it. It feels like nonsense being able to see a place and not being able to access it as easily as it would have been before that border was there. It’s a weird feeling. You still have to follow these guidelines and rules about accessing these places, and that takes away from it.

I had booked a tour of Writing-On-Stone and when I got there, there was a big group of people, and there weren’t any other Indigenous people in the group so I didn’t go on the tour. I didn’t feel like being in that environment without any other Indigenous folks. The way that I accessed these places didn’t always feel that great. Even Okotoks, that’s a culturally significant place for Blackfoot people and when non-Indigenous people relate to it, they think it’s a big rock and they climb all over it. It’s a sacred spot and it’s been vandalized. The pictographs are not visible anymore because of the way other people are using that place.

That gets to what I’m thinking about. How you talked about access and how borders or government agencies like the park service are there as intermediaries. Like with Ninaiistako, you could see it right there, it’s in the same mountain range as the Alberta Rockies but it’s still just out of reach. And with Writing-On-Stone, correct me if I’m wrong but you can’t tour it alone, you have to tour it with a guide?

Mhmm, yeah so it’s a restricted area.

One of the things that made me start this project was when I was driving through Lethbridge with my aunt and we drove through an overpass and she told me the Blackfoot name of the place under the overpass. Now it’s a ditch with garbage and a fence…

Most people know you for your portrait paintings, particularly of Indigenous sitters. You describe these works as “correcting the untruthful representation of contemporary Indigenous people”. Would you say that TSIMA KOHTOTSITAPIIHPA is a corrective portrait of Alberta in the same way?

Yeah, I think so.

I think that this map is a lot more personal. I guess the portraits are personal too, but I think the map is one small step towards people relating differently to what people know as Alberta. It’s just one Indigenous person’s relationship with this place and hopefully people will relate to Alberta differently and understand that there’s more than just Edmonton and Calgary.

One of the things that made me start this project was when I was driving through Lethbridge with my aunt and we drove through an overpass, and she told me the Blackfoot name of the place under the overpass. Now it’s a ditch with garbage and a fence but that made me think, “oh wow, that was an important spot at one point, these people have no idea that that place has a name.” I didn’t know that it had a name either, so doing this map was like uncovering that for myself.

Last year, TSIMA KOHTOTSITAPIIHPA was acquired by the Edmonton Public Library for display in their downtown branch around the same time it was being exhibited in the library space at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery. What is unique about the work that lends it to the library context?

There are all the different aspects of the installation that are interactive, like the book I created that brings more context to the map. The book has photographs and names of the places on the map, so you can open the book and match it to the map and see photographs of the place. I wanted to include this book to place people back on the ground and not look at the land from this above sort of way.

I like the idea of it being in a library. Art outside of the context of galleries is exciting to me. Anyone can go to the Edmonton Public Library and interact with it. The library context is more inviting to sit down and spend time with the work. In a gallery, I think people feel more pressure to look and move on. It’s not the best place to be like “oh I’ll sit for a half-hour and dig into this.” I thought the Edmonton Public library would be a nice place for it.

We had talked about Ninaiistako, Chief Mountain, across the border in Montana and not too long ago you took up skateboarding and painted Ninaiistako on one of your boards. You also used two decks decorated with photos of Blackfoot grasslands in your Edmonton public art installation, Nitsiipowahsiin. How is skateboarding connected to land? Or how does it add to being an artist?

I’m not good at skateboarding. I started to try it more during the pandemic but I’ve been interested in it my whole life. I got my first skateboard when I was ten, and in grade eight I used to go to the skate park all the time with my friend. When I moved to Edmonton in 2016, I got a nice skateboard to cruise around on and it was nice that it was something I could come back to.

With Nitsiipowahsiin that had the two skateboards in the window, I talk about home and belonging. I was looking at alternative places for home, especially during the pandemic when a lot of people had to stay put. So I think for me, one form of home is picking up skateboarding again. I think it is also a way for people to relate to the spaces around them differently. Particularly in that project, putting the photos of Lethbridge onto the skateboard felt right, like these are all different forms of being connected to home.

Ninaiistako (Chief Mountain) was on the other board. My mom used to always draw Chief Mountain so when I was young she’d show me her drawings and they always stuck in my mind as a place that’s special to her. I could have just printed it on paper, but a skateboard feels special. I’m taking it with me so I’ll be skating somewhere and I still have that image with me. It feels nice in a particular way.

After living most of your life in Alberta, you moved to Vancouver to pursue an MFA at Emily Carr University. At the same time, you self-published your book a portrait of you bookending the last five years you spent painting the people of Treaty Six territory. Does it feel like you’re transitioning into a new phase in your practice?

I definitely feel like there is a new chapter happening. I know that my work will be a continuation of what I’ve been doing, but it feels like I’m ready to try some new things. Right now I’m experimenting and trying to dig in to what I am trying to accomplish with my practice and how I want to go forward. Even switching from acrylic to oil over the summer feels like a pivotal point. I think I’m definitely entering into something new and I’m really excited to see in the next few years where my work is going to go.

Me too. I’m excited to see what happens and I’m sure a lot of other people are as well.

I’m actually very scared but I think it’s going to be good.

I was just talking to somebody today who said that if you’re too comfortable, it’s not good for your practice. It’s good to be a little bit uncomfortable.

Totally.