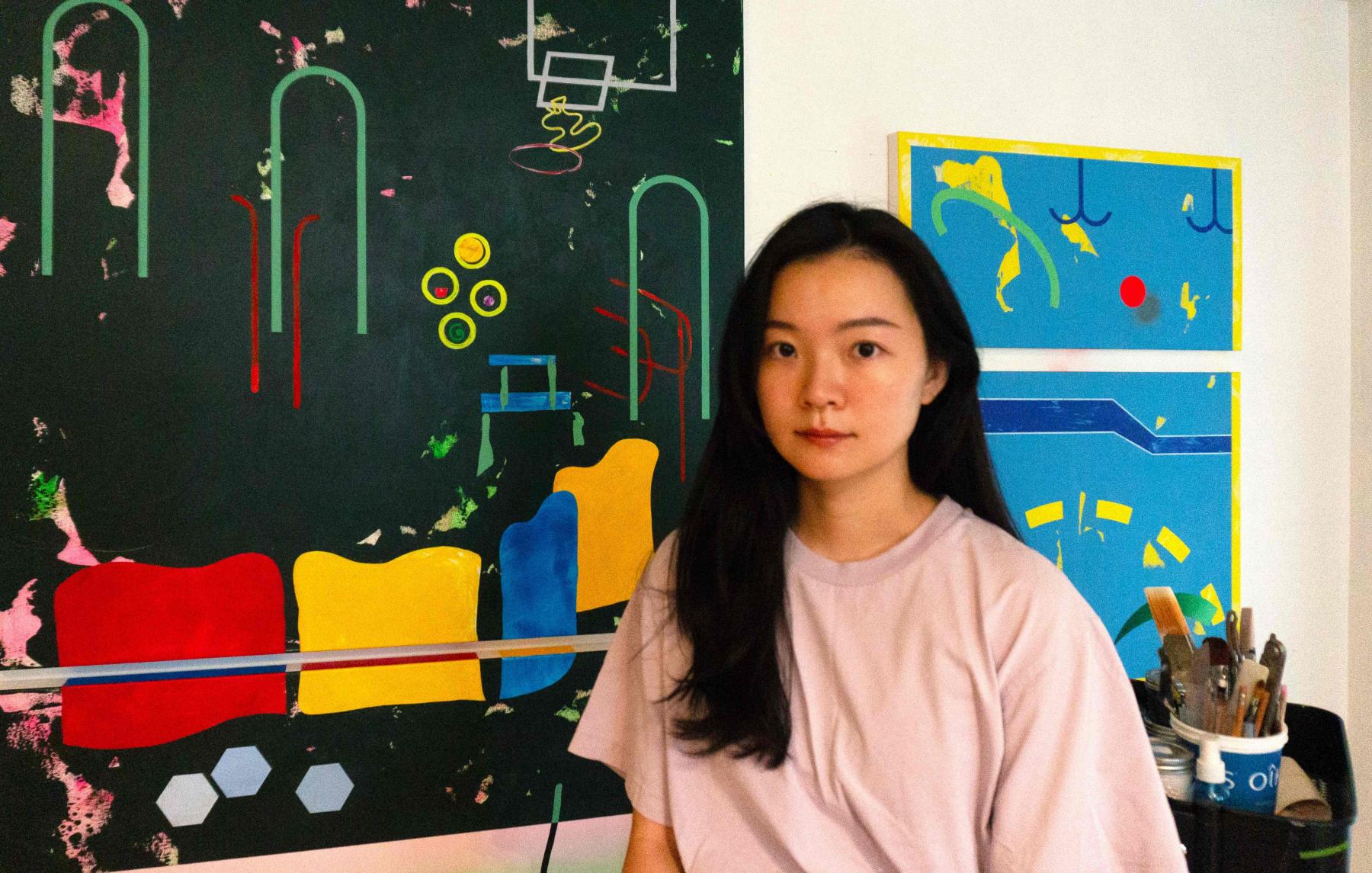

Photo courtesy of artist

As Brubey Hu and I are friends, collaborators, painters, and alumni of Zalucky Contemporary (a gallery in Toronto), I’m privy to the symbols, scenes, and impulses that permeated through her recent exhibition, Islands of Departure 离别之屿. Hosted by Zalucky in the spring of this year, Hu’s colourful diptychs sprawled characters and objects (both familiar and unfamiliar) across the canvas and onto the walls of the gallery. The space between each pair of paintings pulsed with a bright fluorescence; its glow reminiscent of how the winter snow outside looked before it began to melt.

The uncanny nature of the work led me to seek more sense of it through a myriad of written formats: Experimental text? An interview? A response? A formal review? With pointed obfuscation, Hu’s purposeful deconstruction of place, identity, and memory asks the onlooker to call upon their own index of memory. This desire for connection and collective reading rendered the evaluative form of a review, or writing toward a complete encapsulation of the show, irrelevant. My inclination isn’t about liking the show or not liking the show, but instead, the porousness of understanding the show itself. How could value judgements be placed if one’s own reading of the work is of cumulative importance too?

Both for our growing friendship and for the many times mutual friends have noted the synergy between our two practices, I am much more attuned to Hu’s processes and artistic motivations than the average gallery visitor. While me, as an artist-writer, engaging Hu in some wordplay about the show (and beyond!) might therefore seem like it makes the most sense, I won’t give it to you that easily. Instead, we’re seeking to write within the spirit of the work itself. In codes, words, tangents, images, Hu and I offer a text that’s a bit of everything—a meta exercise of sorts—where we can relish in the subjectivity of things we’d like to chat about, both linearly and nonlinearly. In the conversation that follows, we talk about domestic spaces, language, figurative distances, and spray-painted utility markings on city streets. Since none of the standard formats of art writing quite fit the bill, moving to our own rhythm felt like the right choice. This text seeks to weave in and out of these writing structures as it suits our dialogue:

In and out of language, script, glyph, symbols, words, meaning, and phrasing to both elucidate and decode. Let’s go!

When we as artists make work, we are also constructing a maze. We ourselves know the way, and how to get to the end, but it's not the same adventure for all viewers. Once the work is out of our hands, we have no control over how others perceive them.

Philip Leonard Ocampo: Ok, so I originally envisioned this text as encompassing different formats, including a review. Your exhibition, however, challenges the propensity of this conversation to serve the function of a review. The importance of how someone can be in tune, or alignment with what you're literally depicting on the canvas is intentionally variable. What are your thoughts on the legibility and readability of your works? What is the importance of misunderstandings, misinterpretations?

Brubey Hu: We are both BIPOC painters living in the West for years—your entire life being here, in your case. We've been discussing the notion of illegibility for a while.

I can definitely see the reason why you mentioned that people might leave the exhibition with some questions: that was also my intention. Most gestures I put on the wall were not legible at all as they were fragmented words and phrases scattered in the space. They were meant to be riddles, for the viewers to guess, to have their own answers, to piece together their own interpretations. Many of them are Chinese characters. An example would be blurring the lines between the punctuation marks and Kanji strokes. Or bracket marks, could represent something said inside the mind. They already have meanings behind them. Why should they be a secondary thing to Kanji characters, or the language itself?

I appreciate this kind of distance between viewers and myself, and they will come to the show and share what they see in the work. In Insomnia, I painted the view in my current bedroom. The title comes from my difficulty falling asleep back then and staring at the objects and artifacts in my room. At the opening of this show, someone approached me and told me that elements of the painting reminded them of the CN Tower. I thought this was an interesting interpretation, and because of the rectangular shapes that look like buildings and the green gestures that resemble plants, people read it as a cityscape or a nightscape. I'm not going to deny that my subconscious is perhaps playing with me. I finished this painting earlier this year, and I've been living in Toronto for three years. Maybe the cityscape that includes the CN tower as the landmark is ingrained in me now. I might have incorporated it into the painting without knowing.

Your paintings are like Rorschach tests. Anyone can look at a painting of yours and define the work for themselves.

This reminds me of an interview by a Chinese artist named Hu Xiaoyuan. She describes, “Even if I describe my work to you down to the last detail, you can never ever go through that path from the same entrance to achieve what I did”. When we as artists make work, we are also constructing a maze. We ourselves know the way, and how to get to the end, but it's not the same adventure for all viewers. Once the work is out of our hands, we have no control over how others perceive them.

I appreciate this aspect because this also applies to my daily life. Whenever I talk to people, I want to know their points of view and lived experiences, which enables space for each other to reach a consensus.

𝘐𝘯𝘴𝘰𝘮𝘯𝘪𝘢 (不眠), Acrylic, paper, and vinyls on canvases, 2024, Documentation by Em Moor

Consensus! I like to think of it as also finding shapes in clouds. All of these interpretations contribute to the continuity or the consensus of the mythology and the history of any one work makes it feel collectively understood.

There's got to be some commonality between the differences, which is again, going back to this idea of the divide. With my background also in visual communication, I use symbols or icons that are composed with seemingly effortless strokes and clean shapes, but they resemble something that’s way more complex in reality. I'm drawn to this method of simplification, or translation, and giving it meaning that allows different possibilities.

In the text for Islands of Departure 离别之屿 , your recent exhibition at Zalucky Contemporary, the description mentions how the reflection in between the diptychs actually shortened the gap. Tell me more about this.

We're all different people, even though we're labelled as Chinese, Filipino, or whatever, particularly in the context of Canada, we're immigrants from different places. I feel the need to include that gap in physical form, as a metaphor for the distinctions among us. I want to leave room for the viewers to enter with their own narratives, with their own cultural baggage. I enjoy the conversations with other people, who bring in viewpoints I never thought of. This process is a reciprocal encounter between different beings. The coloured reflections represent my yearning to connect with others. This gap shortening is also about bridging the cultural differences and active/adaptive gestures of connecting because the reflection is also relative to where it’s situated.

I’m curious about how these more amorphous understandings of distance might correlate to the very tangible format of the diptych in your work: If I were to separate the two canvases by the full length of the gallery wall, by virtue of the continuity that's happening across all of them, it would still feel like a diptych to me. Do you have any thoughts on the distance of a diptych, or what the threshold is in terms of being close and being apart?

It depends on the content of the painting. I was thinking two-dimensionally as I did my sketches digitally. But in terms of playing with the distance of it, I tried this method on one painting. If they can be displayed in the gallery setting, it would be ideal to have them across from each other on two facing walls, or maybe at a corner, they don't have to be just on one wall. The continuity from one panel to another is facilitated by the colour palette, symbols, shapes, and motifs that they share in general.

...deconstruction of spaces and objects speaks to my mentality and reality of migrating from one place to another, that I am disoriented, in chaos, that I am leaving many things behind, that I am in constant encounter with new people and new things, and I gradually earn more memories.

It’s worldbuilding! The proximity that the works have to each other is purposeful, as you've mentioned. It's immersive in the way that this fluorescent paint allows the sides to glow, and a viewer can really fixate on that column.

From Xiamen to Vancouver, from Baltimore to Toronto: the various stops in the lifetime of becoming within a transcultural context come together in the arena that is your painted surfaces. Do fragments of these various places appear as any legible gestures or marks in the works that you're making?

When I visited my hometown Xiamen this summer, I visited the home where my grandparents passed away. It’s the last space that I stayed in before emigrating to Canada. I felt really strange when I entered the empty apartment that was ready to be sold, rather than a home filled up with personal belongings that resembled the memories of my life there. It's not just the architectural space itself that gives us emotion, but also the objects that were once there.

Physically being in that space again would trigger the memory of living there. Since the elements in one space don't necessarily work together nicely in one painting, I usually end up piecing things together: one element from this place and one element from another place to compose one painting. This deconstruction of spaces and objects also speaks to my mentality and reality of migrating from one place to another, that I am disoriented, in chaos, that I am leaving many things behind, that I am in constant encounter with new people and new things, and I gradually earn more memories. Painting, to me, is a way of giving these sentiments an outlet, to have them manifest in this two-dimensional plane.

Architecture isn't just architecture, right? It's the framework in which we can live our lives.

I know that a lot of the scenes that you're depicting, or the moments that you're recalling or deconstructing and reconstituting are that of domestic space. I've always thought of your work as really existing outside of time in its own sort of vacuum of space. Do you think domestic space is a suitable meeting place for both our waking lives and also our dreaming lives?

When we're painting, we're also dreaming. We're creating this imaginary space that belongs to nowhere, and this lack of placeness is something I’ve felt for a long time, migrating from one place to another, bringing in my own cultural baggage. It is never complete, I feel more like a hybridity. I dream as a way to retrieve memory, or to return to people I am no longer able to meet. My mom told me that she dreamt about my grandma just like in my mother’s childhood when her mother was still alive. Dreaming can be a portal between two worlds, the living and the dead. At least I’d like to think that I am still connected with them, through dreams.

Domestic space is a space of leisure and solitude and safety, you know? Domestic space can be, at its most idealistic, a safe space. It can allow for introspection and allow for catharsis.

Domestic space is always my safe space where I can turn inward to heal or contemplate whatever situation outside that gives me emotions and aggression. It’s essential, and an extension of myself.

This psychic space, or this experiential space can encompass us at our most leisurely restful and introspective.

Domestic space takes on a feminine identity in my exploration, if we have to compare and put it under a dialectic of yin and yang. It’s about being with oneself and exploring inward, and it has long been associated with unpaid domestic labour. I've recently been doing research on domestic labour too; we spend so much time in these spaces, taking care of and maintaining our surroundings as a form of self-care.

How do we divide or distinguish the function of a space like a living space?

What is living space?

It has a lot of functional objects, appliances, and personal belongings in this space, and we see traces or residues from day-to-day living, such as a used mug, an opened bag of chips, a half-finished soy sauce bottle, and so on. When these traces are transformed into the pictorial plane, do they still mean the same thing? Do they have their own functions of hinting at something more profound? Showcasing them in the paintings in a more sterile space like a gallery, are their meanings transformed again?

When people asked me how I felt about the show, I said that I was glad to see that outside of my studio space, because I got to see the work outside of a familiar setting (my studio and my home), and that I was able to respond to the gallery space directly. It feels like a blank canvas to me, allowing me to draw gestures directly onto the wall.

Not all the gestures hold meanings and identities anymore; they are decontextualized from the original dwelling, condensed into 2D forms, losing their original meanings, while building new connotations and encounters. They are translated from the mundane and fleeting moments to a gesture inviting questions. In the studio space, I reconstruct a “living space” with relics and reveries; in the gallery space, they lead me to express reflections on that very moment.

𝘐𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘋𝘦𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘶𝘳𝘦 (别离之屿), 2023, Acrylic and vinyls on canvases

𝘐𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘋𝘦𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘶𝘳𝘦 (别离之屿), 2023

On the idiosyncrasies of spaces: think about what we encounter in the wild world of everyday life. The only New Year’s resolution that I ever followed through on was a commitmet to always take the photo no matter how mundane or how boring it seems, if compelled to. In a purely intuitive sense, are there any motifs or, reoccurring aspects of everyday life that you feel drawn to? What do you see in real life that makes you stop in awe?

I go on walks quite often. Have you noticed that there are so many marks on the ground? Near construction sites usually, spray-painted arrows, symbols, text, and so forth.

I'm also so drawn to those.

They are weird, fluorescent marks made amongst the grey cityscape. When I am walking, I don't have other things to attend to besides being in my mental space. But looking at the surroundings, they are like signals or messages sent to me through interesting compositions of shapes. That's something I would take pictures of and potentially translate into paintings.

I am drawn to a lot of gestures like this, because they’re fleeting. When I return, many of them are not going to be there anymore. They are so ephemeral, since a construction site is not going to be around forever. Looking at them, I feel something is trying to be communicated, about their life, about their destiny. I can't ignore the message. I try to capture something that resembles mundane encounters.

Do you think we're specifically attuned to these sorts of things because we are artists? I'm sure lots of people just walk with their eyes fixated on the destination.

Maybe? There's a Chinese term called 缘分 (Yuán Fèn). To me, it means a fateful encounter with this particular moment, person, or object. My life, my personality, my ideology, are all influenced by these very moments of encounter, they might not be something grand but it is precisely the accumulation of these microhistories that make each of us unique beings in the world.

The last sentence of the exhibition statement references how it is mainly every day where our most personal identities have formed. Maybe in this way, we cannot feel how we shape our personality. But what if it's hundreds of thousands of small things so mundane happening every day that shape our personality, shape our ambition, shape everything among us. It makes life feel more beautiful. If you're attuned to that sort of thing in your own life, it just unveils a whole world around you!

These sorts of gestures along the sidewalk that you were talking about, so evocative, so expressive. For me, that is the exact way that I think language and language systems can play a role in art. There’s a tonal difference between writing “I’m screaming” and just writing “!!!!!!?!?!?!?!?!”

These gestural, quick expressive lines, at least in the work that I make, is how I'm approaching language and its role to get to a deeper feeling, rather than language in its descriptive sense. What role do language systems play in your art making?

I totally resonate with you. This kind of gesture happens in both your paintings and mine, and because of the way they are constructed, it indeed suggests the form of a literal language, and the hand gestures of how you would write a sentence. The lines can mean different things and are open to interpretation, right? It also alludes to an aphasic state that I remember having when I first came to Canada, not being a fluent English user. I use line forms to evoke and capture this illegible state, a state that many language learners and new immigrants endure. To me, this line could be directional, could lead to something, but it could mean something more specific to another person. And this returns to the point of giving room to the audience to have their own interpretation. In another way, it's a nice formal element to add to the paintings. It could add another layer and guide the eyes to go around. Somehow similar to those sidewalk marks that we spoke about. It's a coded language.

“Hmmm I don't know what's going on here, but I fucking love it.”

There is a Chinese saying that the way you write reflects your state of being, 见字如面 (jiàn zì rú miàn). The state of being is revealed from the ways one writes or creates calligraphy, from how strokes coordinate with each other to form a character, and how the overall shapes occupy the pictorial plane.

You're more interested in the glyphs whereas I’m interested in the script. Even these glyphs, they're just an assemblage of smaller lines, right? So when you peel back the layers and point to a broader expressiveness that transcends one linear reading.

Sometimes it just resembles motion, right? It could be body language, or as you write with your body, it doesn't necessarily have that kind of literal meaning. It would be too straightforward. Why does it need to be prescriptive? Sometimes adding that specific word onto a painting feels like I'm directing the viewer to do a certain thing or to think a certain way, and that's not my intention.

I think wielding that agency is powerful, right? In our practices, our ability to guide or suggest or to illuminate a path for a viewer to engage with, I think it takes a lot of restraint.

Isn't that how we all learn things from each other? Be more sympathetic to other people's experiences? It’s a mindset that we need to adapt to collectively, acknowledging that we are all different beings, and yielding room for understanding and care.

It's not repetition, but multiplicity. It extends. It expands outward, rather than repeating itself.