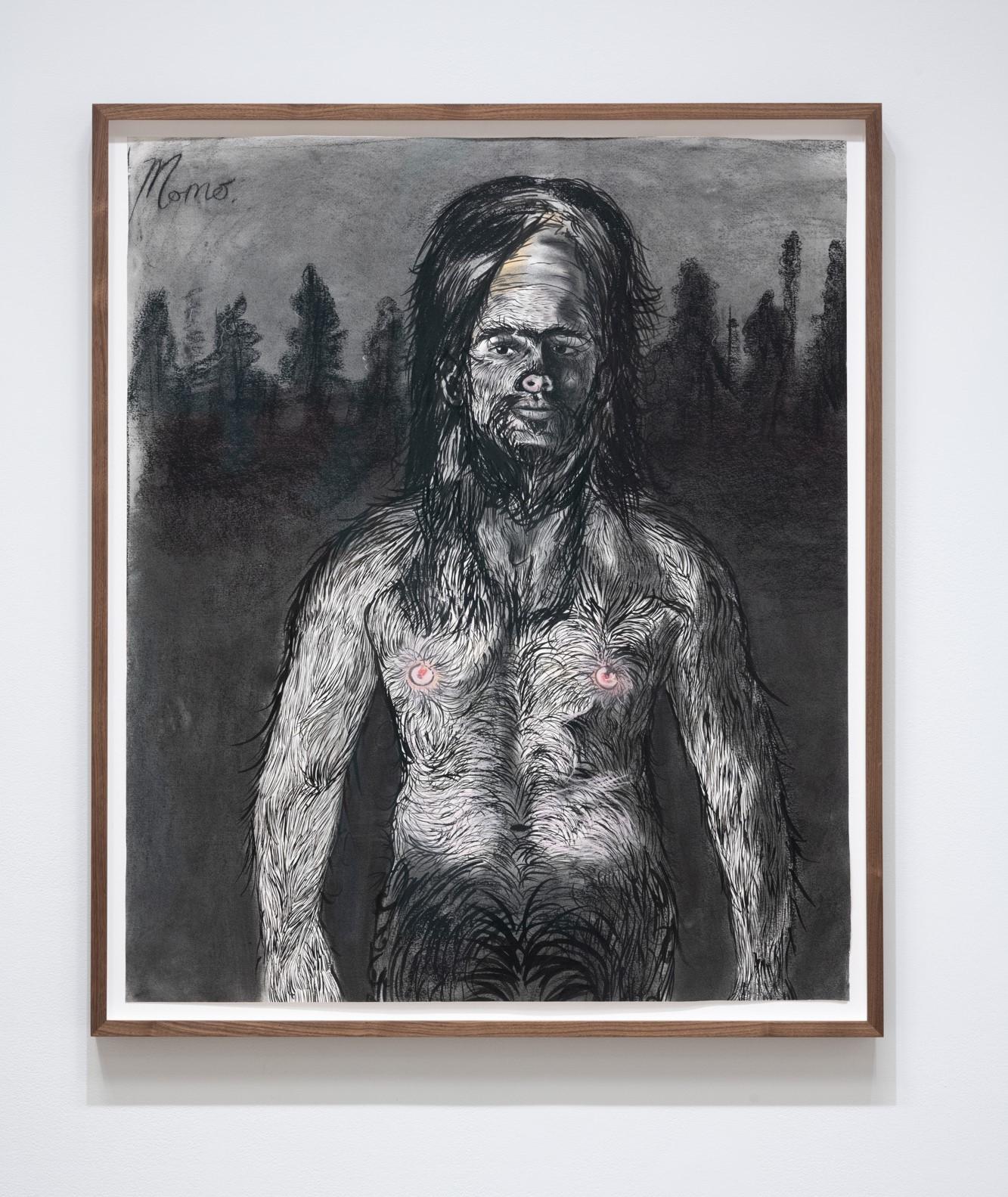

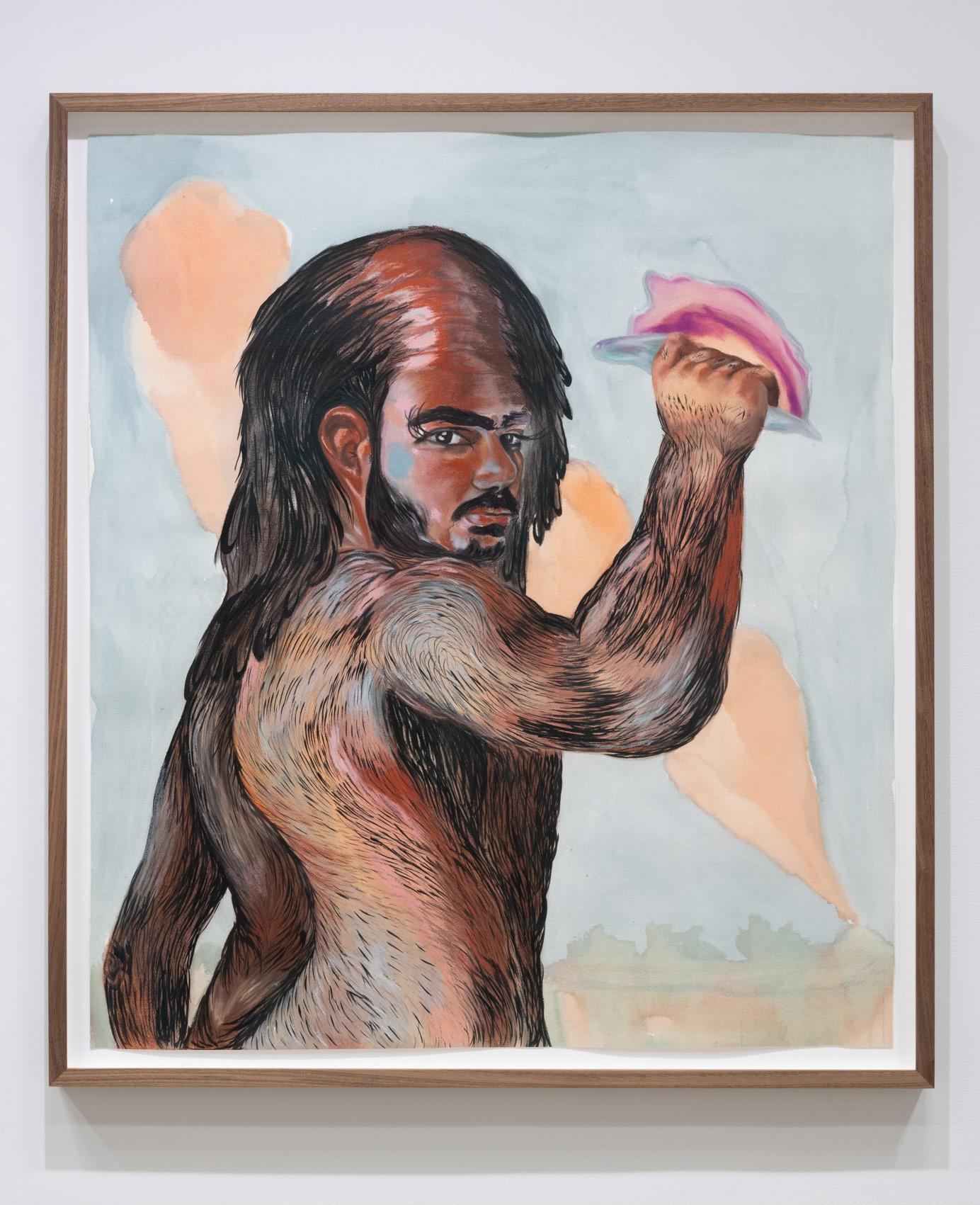

Amanda Boulos’s “Momo” and other “Palestinian Sasquatches” at Centre Clark, Montreal, Dec. 2024. Photo by Paul Litherland

Love and Race on Paper and in Paint

I spent a few days at Columbia University’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Library with the collected papers and correspondence of the late Palestinian-American literary scholar Edward Said (1935 – 2003). An errant scrap fell from one of the files. On it, Said made a list with the names of two of his love interests, and the costs and benefits of pursuing those relationships. One was white, and the other with ties to the Middle East. ‘Fitting-in’ with Said’s Anglo-Saxon academic set, on the one hand, and with his network of Palestinian and Lebanese colleagues, family, and friends on the other hand, was the main concern, as I recall. I didn’t photograph it so I can’t be sure. It seemed irrelevant, an odd bit of archival gossip, or worse, a diminishing look at the merely pragmatic reasoning of a giant of 20th century thought. But looking back on this intrusion of Said’s private, romantic life into the record of his professional one, that little piece of paper has steered my sense of his work as a critic of Orientalism in literature, policy, film, and occasionally art. His anxious exercise in family planning resonates with writing on the “affiliative bonds” amongst European and American experts on the Arab-Islamic world – on the way in which those bonds have constituted something like the authority of family relationships for white authors who regard the minds, customs, and bodies of Arabs as essentially, or “ontologically and epistemologically” distinct from those of Europeans.2

Said’s views were unpopular, before they were widely adopted by critics of colonialism across the disciplines. His receptionist told me, in hushed tones as though the danger was still present, that he had bullet proof glass installed in his Manhattan flat. All these years after Said’s death from Leukemia in 2003, and with mounting intensity in the last year, that danger has manifested in a campaign of “scholasticide” targeting Palestinian poets, writers, academics, and students in Gaza.3 I can’t be the only one who wishes he were here now, to help turn this murderous tide.

I was at the library to study the reception of Said’s work in the discipline of art history – one founded on a comparative method, for example, between Renaissance and Baroque style. His relationship score sheet unexpectedly set the whole business of comparisons, between traditions and people, between Arabs and Europeans, and between white and brown bodies, desired, colonized, and policed on account of their difference, in a more felt context. Taking the work way too seriously, as grad students do, I saw my own, unfolding break-up with a white woman as an eviction, a threat of not ‘fitting in’ with a tradition and an authority that I’d come to covet. To ease the sting of it, I attached myself to the work of the art historian Linda Nochlin, perhaps a substitute white, liberal feminist, but also importantly, the one responsible for the transmission of Said’s ideas into my field. It was there, in salons on 19th c. French art with Nochlin and her ilk, that I found the politics of race and love described in an adequately messy way.

( (_Musée_du_Louvre_.jpg)

Eugene Delacroix, The Massacre at Chios (1824). Sourced Via.

In Delcaroix’s The Massacre at Chios (1824) the private parts of Said’s brown and white ambivalence are made public and mapped onto the history of the Greek War of Independence against the Ottomans. The right group shows a horse-mounted Ottoman soldier abducting a classicized nude over a dead Greek mother with a baby suckling at her breast. The left group includes more suffering Greeks pleading for mercy from encroaching Ottomans. The central group includes a fallen, mostly nude, Greek man, although his complexion is darker than the rest, leaning against a slouching woman. The War was a fierce one that the French public observed with overwhelming support for Greek independence – for a Greek victory over the last bastion of a beleaguered Islamic Empire. French love of all things Greek is, for analysts of the painting like art historian Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, the key to Delacroix’s sympathetic treatment of the scene’s victims. But its deeper code is revealed in the artist’s notebook, on scraps of paper like the one I found in New York, recording his private thoughts on that oversized, fallen brown Greek in the central group.4 The figure was based on sketches of the artist’s “mulatta” lover and model named “Aspasie.” For Grimaldo Grigsby the darker side of French philhellenism is expressed through this transformed, re-gendered image of a mixed-race woman. In tortured and libidinally-charged journal entries Delacroix gives voice to a widespread fear of miscegenation and the sullying of the European race.

Fear of a Brown Planet and the Arab “slag in the melting pot”

Fear doesn’t figure in Said’s accounting. The tidiness of his list would have kept it at bay. And the fear Delacroix channels in his work is dulled too, by his lust for Aspasie. Nevertheless, this emotion seems a part of the landscape of race and love, then and now. It was for me, staring-down my own break-up, fearing being alone, naturally, being too brown for the white words I studied and exchanged with my partner, and finally, scared of sounding too white for this brown body after losing the validation of that partner’s company. The air of control in Said’s list kept my fear of all this at bay too.

Menacing stereotypes of Arabs flooded the silver screen and the mass media in Said’s time, and in my youth. Marauding Libyans in Back to the Future (1985) stand out for me, but the type was all over the place, lurking in the shadows to snuff out the lights of Western civilization with car bombs, Molotov cocktails, or Russian weapons. Those pulpy images of what Said called in the 70s a “latest phase of Orientalism” bore a striking resemblance to Delacroix’s and his peers’ in the 19th century. In the US, before Said established himself with a mastery of white words, delivered so eloquently from a trembling Palestinian pen, Rudolph Valentino (1895 – 1926) played across the white-brown divide to popular fears of an Arab menace. In The Sheik (1921) and The Son of the Sheik (1926), his character was responsible for drawing the “new women” of the 20s into the cinema, and the ire of white men whose Victorian uprightness was coming to be seen by those same women as a thing of the past, and as no fun. For all his ethnic-masculine risks, Valentino was a responsive lover and dance partner, and a person whose characters communicated emotions, including misogynistic ones, before measured opinions. On balance, this misogyny was softened by his characters’ innate brown passivity, and the “sunlit dream of sexuality” they promised.5 These attributes would have appeared in the ‘pros’ columns of his adoring female fans. But their affection was regarded as the direst ‘con,’ according to the prevailing anti-immigration, nativist ideology of the 20s. His swooning fans were flirting with “race suicide,” and introducing “a slag in the melting pot” of a rightfully Nordic-Anglo-Saxon gene pool.6

_02.jpg)

Rudolph Valentino and Vilma Banky in The Son of the Sheik (1926). Sourced Via.

.jpg)

The Son of the Sheik (1926) poster. Sourced Via

Early 20th c. American films gave us Orientalist lore, rather than Arab representation. Alas, Valentino was Italian-American, and his character in The Sheik is of mixed, partly English ancestry. During Valentino’s fall from grace in Hollywood, other actors like Douglas Fairbanks (1883 – 1939) in The Thief of Bagdad (1924) filled in for this doubly missing or white-passing Arab in the film business. When Arabs did finally make it onto the silver screen their appeal was safer than Valentino’s. Egyptian actor Omar Sharif (1932 – 2015), for example, was cast as “Sherif Ali ibn el Kharish” alongside Peter O’Toole (1932 – 2013) as T.E. Lawrence, his white savior, in Lawrence of Arabia (1962).7

Some progress has been made past the stereotyping, division, and conquering of Arabs in and beyond film, in expanding rights movements against Islamophobia and Arabophobia, and for Palestinian liberation. And within these movements the roles of white allies have also become encouraging. According to one of the many circulating slogans for the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) movement, white saviors are no longer needed in a situation where “We’re not freeing Palestine. Palestine is freeing us.”8 But such gains are made alongside the single most devastating attack on Palestinians since the Nakba of 1948. Arab life has never been more callously devalued, by the IDF, of course, but also by the powerful nations that quietly enable their operations.

Agreeable Arab Funnymen and the White Women Who Would Love Them

Humour in such hopeless times is as important as ever. And maybe with it we take a new turn in that history of otherwise humorless Arab representations in European and American art and entertainment. Examples of nuanced and funny Arab characters are available in the TV series Ramy, created by Ramy Youssef (b. 1991) and starring Youssef and his peers in the Arab-American comedy scene, Dave Merheje (b. 1980) and Mohammad Amer (b. 1981). The show follows Ramy and his pals on their awkward twenty-something boyish rites of passage, both religious and secular, through New Jersey and abroad on more invested searches for life partners and spiritual salvation. Art historian Alex Seggerman attributes the characters’ depth to their conflicts between sexual and religious drives, and to the split-scene of their comedic attempts to find authenticity – at the juncture of Muslim religious life (i.e. in mosques and madrassas, at Mecca, etc.) and profane American life (i.e. in strip clubs, casinos, make-out bedrooms, and bars).9 The humour of the show results from these tensions for her. On the model of George Costanza in Seinfeld the boys of Ramy get laughs by subjecting their poor yet earnest lifestyle choices to the scrutiny of the audience’s conventional morality. So it is that Ramy’s friends settle an argument about where to go for a bachelor party - the choices are a strip bar and a magic show, by noting the “demonic” presence of djinn at the latter and the halal (lawful) medium of dance for artistic expression at the former. More provocatively, in another episode, the Muslim duty of zakat (charity or almsgiving) is evoked through quick cuts to images of the Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca in a scene where Ramy helps his wheelchair-bound friend with muscular dystrophy to ejaculate, for “medical reasons.”10

In two 2023 films starring Youssef and Merheje respectively, this image of a well-meaning and comical Arab masculinity is given a different inflection, in darker comedic arenas with higher moral stakes. Sometimes I Think About Dying (Dir. Rachel Lambert) stars Merheje as “Robert Naser,” a goofy cinephile love interest to “Fran,” a lonely white office worker who suffers from suicidal ideation. Robert helps the forlorn, defensive Fran past her fears of connection and vulnerability by the film’s end. Though the relationship is not consummated (their one on-screen kiss is interrupted by a smoke alarm), a noteworthy twist in the story of Arabs on film is worth pointing out here. Sometimes dispenses with the brown and white buddy dynamic of O’Toole and Sharif in Lawrence of Arabia to more humanely cast a brown, male savior in a complex and reciprocal relationship with a white woman.

Rah Eleh, Victoria Secret Karen, Clay ceramic and paint, 12 x 5 x 3 in

Rah Eleh, Doberman Karen, Clay ceramic and paint, 7 x 6 x 5 inches, 2024

In Poor Things (Dir. Yorgos Lanthimos), the dynamic between a white woman named “Bella Baxter,” played by Emma Stone (b. 1988), and Arab-American actor, Youssef playing the supportive, smitten and white-passing “Max McCandles” is more complex, and more perverse. Instead of office workers’ malaise the moral problems in Poor Things are intractable: female sexual liberation and subject formation under patriarchy, the bioethics of experimental organ transplantation, and a host of stubborn social, economic, and political problems like war and famine and the needless death of babies from both – surely among the many “poor things” referred to in the film’s purposefully trite title. Following a suicide and re-animation under the knife of McCandles’s mentor, a maimed eunuch named “Dr. Godwin Baxter” (played by Willem Dafoe) Bella begins her new life with the transplanted brain of her unborn child. Her path leads to a moral awakening, eventually. But it’s hard-earned after elementary lessons in speech acquisition, advancement through the phallic and genital stages of psychosexual development, and the ‘ins and outs’ of sex work. Bella’s most transformative lesson comes from a dandyish Black “cynic” who shares with her a harsh view from a Mediterranean cruise-ship of the preventable deaths of children in a post-apocalyptic “Alexandria.” It’s here, in the throes of indignation over the deaths of innocents that Bella becomes fully human.

Like the comedic formula in Ramy, the film exploits a gap between the characters’ actions and the audience’s moral codes. But in this Alexandria scene there is an alignment of the two – of Bella’s horror at the site of dead babies, and the audience’s identification with her in her sadness and rage. Released the year before images of Palestinian infant deaths became so ubiquitous, the scene is prescient. A relative lack of the public moral outrage on which that scene depends, now, when it’s most needed, is striking. The sight of dead children has not led to the universal moral awakening required to stop the genocide in Gaza.

Bella might be the moral compass so many complicit world leaders need these days. And she’s guided in her journey by a Black dandy and an Arab-American actor – by morally instructive, ethnic-masculine characters with links to persecuted communities. Breaking the mold of Valentino’s roles, and a lot like Merheje’s, Youssef’s character is a sympathetic brown helper to a troubled, also suicidal white woman. He follows Bella’s progress and takes a shine to her, in time becoming her fiancée and then her husband. But again, like Merheje’s character, Youssef’s never consummates his love. As the understudy of a eunuch, we’re not at all shocked by his asexual decency. In spite of the progress these films make in the story of Arab representation in American screen culture, the brown-white divide persists in them, enough to see its danger mitigated in loving relationships that never really get off the ground.

In his writing on various pop cultural inscriptions of “white girls,” theatre critic Hilton Als notes the flexibility of the type. In Prince and Michael Jackson, the embodiment of white femininity issues a challenge to the conservatism and homophobia of Black Americans in the performers’ respective hometowns of Minneapolis, Minnesota and Gary, Indiana. The “white girl” in these cases is a device for Black queering, a direct line to Als’s own community of “Black queens” in Manhattan. He writes about ‘real white girls’ too, not just their metonymic appearances, in Richard Pryor’s disastrous romantic life, for example.12 Pryor’s partners, including Margot Kidder and Jennifer Lee, for Als, were both in love and in solidarity with the comedian, sharing a common cause against white suprematist patriarchy. As he puts it: “In some ways Pryor found it easier to be with white women than Black women: he could blame their misunderstandings on race… and take advantage of the guilt they felt for what he suffered as a Black man.”13 Indeed, Als reads this pattern back into his own failed romances with white lovers too, granting that while “no love is perfect… in every relationship with someone outside my race – I focused on the cracks.”14

As in Said’s list, and my own breakup when I discovered that list, the cracks are all too easy to see once things have gone wrong, or once ‘fitting-in’ is raised as a question. Maybe race in loving relationships is a little like a physical ability taken for granted until it’s limited and becomes conspicuous in its brokenness. Race is the surprise trouble that surprises no-one. And so, it shouldn’t. As a 19th century pseudo-scientific concept used to justify colonial adventures and other forms of policing, race from the moment of its invention was broken.

Amanda Boulos’s “Momo” and other “Palestinian Sasquatches” at Centre Clark, Montreal, Dec. 2024.

Amanda Boulos’s “Momo” and other “Palestinian Sasquatches” at Centre Clark, Montreal, Dec. 2024.

(S1. E1.) Romance Under the Olive Tree

Something like the contours of a genre emerge in all this fumbling around the politics of race and love in film and popular culture. In the time of their most relentless, live-streamed slaughter in Gaza, Arabs have become funny on movie screens and TV shows. The only genre that could accommodate this paradox of their representation is tragicomedy, and it’s exploited brilliantly by the contemporary artists Amanda Boulos and Rah Eleh in their most recent works on the topic of racism.

Boulos’s humour is tender. Her “Palestinian Sasquatch” paintings were conceived a couple of years ago for a residency in Banff, Alberta, near the forests where one might reasonably expect to find them. At that residency Boulos’s early sasquatch works were viewed by Indigenous student groups who shared the lore of the creature and its various names in local languages of Cree, Blackfoot, Chipewyan, Dene, and others. The reverence for the creature expressed in these names captured what Boulos had in mind for her sasquatch too, based as it was on stories and images of her bareknuckle fighting champion grandfather - a national hero in Lebanon who ended up working night shifts in factories after arriving in Canada.15 Other men in her family provided models for the most recent batch of sasquatch portraits, including cousins and her brother, expanding the creature’s reach to two generations of beloved Palestinian-Arab men.

Across the most recent four portraits exhibited at Centre Clark in Montreal, traits passed on from the first generation of sasquatches include: a tall, accordion-like forehead; nearly or fully joined thick eyebrows; male pattern hair loss above those ample eyebrows; abundant fur from the neck down; and endearing doe-eyes, each with an off-center, animating glimmer. The species’ new traits include flaming, radiant nipples, elongated earlobes, and long, curled eyelashes – signs of a campy virility, maybe, or an appetite for what Bella Baxter called “furious jumping.”16 New habitats are also provided for the new brood. After Banff, Boulos’s sasquatches are pictured in PEI near her latest residency, in Lebanon with rising smoke from an IDF bombardment on the horizon, and in Palestine on a stretch of beach near the Huleh Marshlands, home to a number of migratory birds before it was drained in the process of Israeli settlement.17 The subtext for these honorific pet portraits couldn’t be clearer: since the Nakba of 1948, and especially in the nightmare of the last year, the honor and humanity of Palestinians has not been recognized. The Palestinian sasquatch, like its distant relative in the forests of Turtle Island, and like Palestinians on the ground in Gaza, is hunted for sport.

Rah Eleh’s humour is sharp, her comedic teeth cut in the overwhelmingly “white spaces of Gatineau” where she grew up queer, culturally Muslim, and racialized. Her work is based in an experiential study of microaggressions over the years, and more explicit racially motivated and Islamophobic aggressions, dodging spit and rocks at her bus stop, for example.18 Her series of four ceramic sculptures based on viral “Karen” videos might be read as a revenge fantasy were it not for their preciousness, their fragility. They are breakable, both physically, (a fifth in the series based on “Central Park Karen” exploded in the kiln), and psychologically as their flailing, collapsed, or distressed poses attest. At a recent showing with de Montigny Contemporary in Ottawa, this feature of the works is clear in a puddle of “white tears” under the “Victoria’s Secret Karen” who, in the video source for the sculpture, lays down on a shop floor exhausted after a confrontation with a Black customer. Like Venus from the seafoam the ceramic Karens emerged from a study of the concept of ‘white tears’ in Eleh’s exhibition “Spoiled Milk” which featured mostly new media works, her usual format.19 They represent a turn to a traditional material and technique of representation, perhaps to emphasize the historical roots of the Karen-type in a more sweeping, Victorian culture of whiteness. The works function as a swan song, or maybe a death rattle for that tradition, exposing its racism, and sadly, its persistence in our time.

Rah Eleh,BBQ Becky (#Karensgonewild), Clay ceramic and paint, 12 x 4 x 4 inches

The others are just as sad: “BBQ Becky” sobs in her palms after calling the police about a Black family’s illegal use of a charcoal BBQ in an Oakland Park; “Doberman Karen” nurses an alleged leg injury after accusing a dog walker of unleashing his pet on her; and “Berry Scary Karen” waves her arms spook-style after telling two women of colour to “return to where they came from” instead of eating berries on her pristine Canadian forest trail.

So how do Eleh’s Karens help in this day of foiled white-brown screen romances and excuses for genocide? At the end of this darkest of years for Palestinians and those paying attention to their extermination, the apparent irrelevance of the moral insight that ignited Bella Baxter’s humanity in Poor Things is signaled by the Karens. They are, for me, effigies to that faltering morality. In our time, public sentiment or rather the part of it that harbors a bias against Black, Arab, Indigenous, and other racialized people, is exploited for personal, political, and economic gain. The Karens tell us this much and remind us that we are in the grips of a moral relativism with a devastating cost for victims of human rights abuses near and far. But maybe in their figuration of impotent hate they can remind us to love, instead.

Since there are four of them, I imagine a match-making scenario, somewhere between the reality TV series “Love is Blind: Habibi” – a Palestinian Edition, and Valentino’s The Sheik, with all the cracks of Pryor’s tempestuous white loves, and Max McCandles’s and Robert Naser’s infantile, unconsummated ones. While these ceramic glosses on the viral Karen videos are no doubt intended as satire by Eleh, in amorous pairings with Boulos’s sasquatches they’d be cast in tragicomic stories, or an interspecies rom-com. I want Doberman Karen and “Momo” from Banff to pair off, and chat about grooming products; I want BBQ Becky to be the one responsible for the smoke on that Lebanese horizon instead of the IDF, smoke from a feast of kofta she prepares for the whole gang; and I want “Berry Scary Karen” to let the berry bush go and save a Palestinian olive tree.