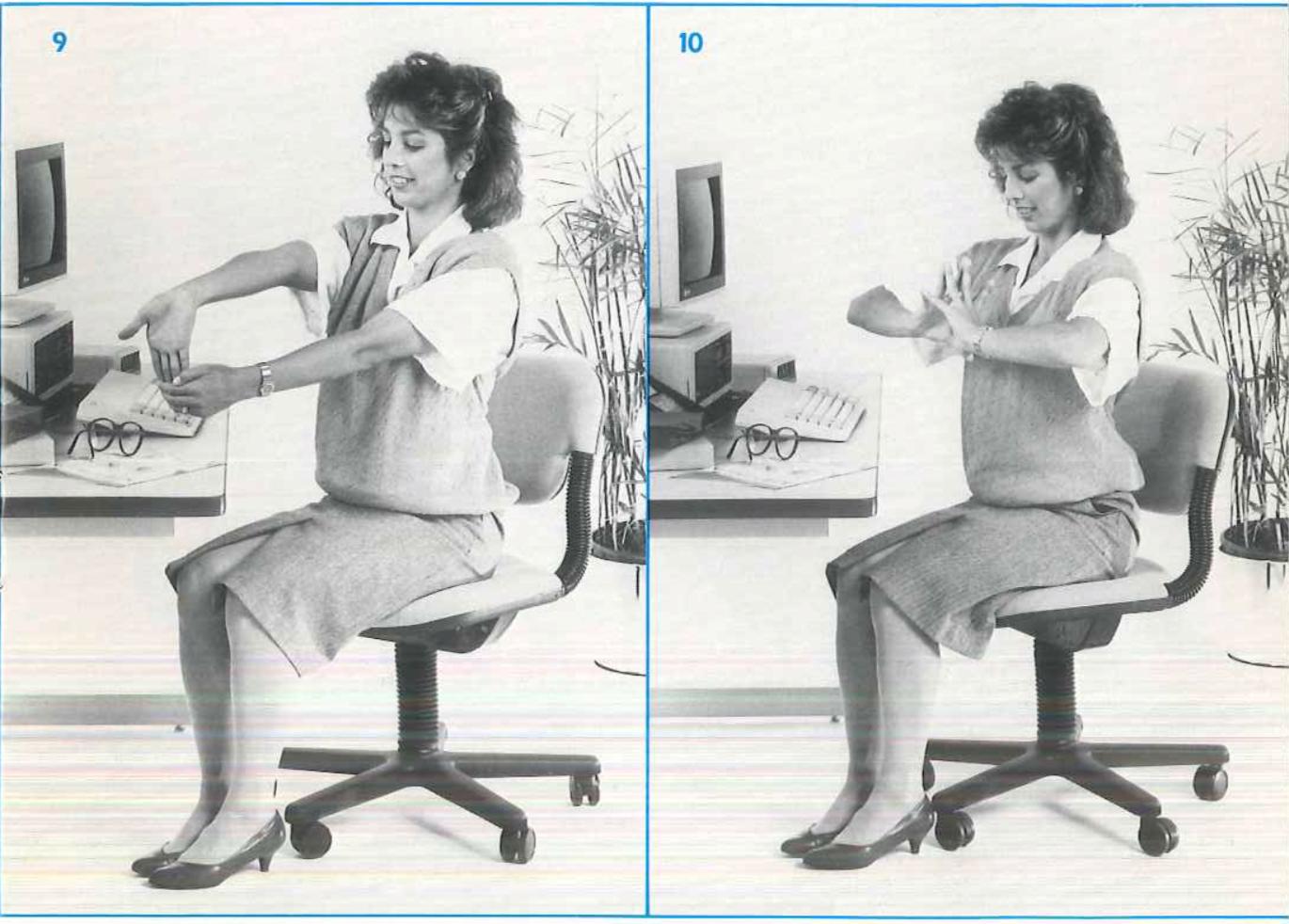

"Illustrations from Tone Up at the Terminals: An Exercise Guide for High-Tech Automated Office Workers by Denise Austin. New York State Library Ergonomics Collection, 1988. Sourced via Shea Fitzpatrick, “using a computer is painful,” are.na channel, 2020.”

Inevitably distracted from the writing task at hand by the tension in my neck, I find myself in a new tab where the phrase “Why is the Aeron chair so expensive?” auto-completes in my search engine. My resentment towards the obligation to work beyond the limitations of my bodily capacity is directed at this object: a top-of-the-line office chair designed by Herman Miller, wrapped up in the legacies of Modernist design and “human factors engineering.” The chair’s glistening curvature promises to cradle one’s wrist, delivering it to the keyboard at an angle so comfortable, one could type forever. It takes on the form of a luxury exoskeleton: rising to meet the body in a perfectly-structured caress. But like a skeleton, in its support, it also constrains. The Aeron is a metonym for ergonomics more broadly, a discipline founded on offloading the responsibility for a systemic problem—the strain of repetitive labour, be it at a desk or on a factory line—onto the individual worker. The fantasy of reprieve offered by the ergonomic chair placates the drive for revolution; labour feeds neatly into purchasing power, entitling the work-weary to rest their behinds and indulge in an individualized, market-based solution.

That is all to say, ergonomics is not just a casual investment in optimizing comfort—it’s an ideology. Obscured behind this well-engineered support system is also an implicit faith in Cartesian dualism, making the body unobtrusive so that the mind can excel at the fore. The highest tier in the office bureaucracy is etymologically linked to a genre of cognitive performance: executivus, “to perform an action or task.” “Executive functioning” refers to sophisticated decision-making; commonly, it is positioned as the mind’s capacity to override the body’s ostensibly more base and instinctive impulses. The very language around “executive functioning” implies a hierarchy between mind and body inherited directly from the Enlightenment. Likewise, a proper Executive Chair—standard sales copy parlance in the online office furniture space—like the Aeron facilitates fantasies of escaping embodiment, freeing the brain from the body’s crude mechanical limits.

Its sleek aesthetic gestures towards techno-optimist speculative futures, a utopia where consciousness is uploaded directly to the Cloud. Of course, like most cyber-idealist dreams, the Aeron’s promise of eluding embodied strain is mostly out of reach. The Aeron was born from an effort by Hermann Miller’s R&D department to design a seat that would comfortably bolster bodies with limited mobility, a rejoinder to the La-Z-Boy that had become standard issue in homes and hospitals across America. But this altruistic intention—designing purpose-built furniture for those that could not labour—was cast aside by Miller management in search of a niche with larger market share.1

"ergonomics is not just a casual investment in optimizing comfort—it’s an ideology."

Now more Silicon Valley status symbol than benevolent design intervention, the chair retails for something like a month’s rent. In its absence, my own humble workstation leaves much to be desired. Locked out of the market for a serviceable seat from which to perform my low-paying position in the creative precariat, I take to yoga with ruthless obsession, throwing back YouTube vinyasa flows with a responsibility bordering on civic duty. I’ve started referring to my right arm as my “trackpad arm,” keenly conscious of the extra shoulder strain it bears from repetitive motion. Each night, I take extra care to stretch the right side of my neck, rolling shoulders gingerly to ward off aches until the next workday inevitably brings their return. Labouring to keep the body fit for labour—just another day on the cognitive assembly line.

Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism details the depression of inhabiting a society where relief from endemic social problems can only be sought through market-based solutions. Solidarity withers in this state, Fisher observes: our capacity for empathy and collaborative problem-solving deteriorates, our revolutionary desires dissipating as liberty is recast as consumer choice. So it goes as I resentfully browse the Internet for ergonomic seats, praying to be placated if I can just select the right product. But reframing the problem of desk neck in the spirit of Fisher’s writing, could we conceive of a critique of ergonomics that draws light to the shared, systemic nature of this burden—refusing the facile belief that salvation will arrive with online shopping?

As Fisher observes elsewhere, the transition from Fordist to post-Fordist labour constitutes the construction of “a dystopia built from workers’ desires.”2 The radical spirit of May ‘68, which demanded freedom from the factory gates, led seamlessly into the rise of “immaterial” labour fuelled by new technological developments: cybernetics and, eventually, consumer-grade computing. That the “desktop” provides the dominant visual metaphor for the contemporary operating system is revealing, gesturing towards the intertwined histories of networked communication and a shift in the status of labour. The desire for alternatives to the physical strain of factory work (and the old-guard hierarchies of Fordist work more broadly) thus transformed into what Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello call “the new spirit of capitalism,” an ostensible “freedom” in the workplace that parlays the libertarian impulses of 20th-century radicalism into a new and pernicious form of subtle domination.3

What if the desk worker’s plight could enliven our thinking about labor relations more broadly? The Aeron chair—and the discipline of ergonomics that it stands for—is built on the illusory fantasy that labour can reach a purely disembodied register, imagining a class of production divorced from the vulgarity of physical work. It masks post-Fordism’s quiet malignancy, its status as a canny re-branding of the same distribution of power between labour and capital that the Left has long rejected. Further, the obfuscation of cognitive labour’s materiality is itself a source of so much harm—from the environmental toll of the data centers that host my words on the Web to the oppressive regimes of neo-colonial resource extraction that dictate earth minerals’ trip from an underground mine to a refinery to your laptop battery. So much is obscured, disappeared by the attempt to cast cognitive labour as “immaterial.”

Perhaps least among these vast harms—although most obviously palpable from my position of privilege—is the physical tax of LARPing as a believer in Cartesian dualism, pretending that for eight hours a day, as I sit at my keyboard, I am exempt from embodiment. No consumer product can—or, for that matter, should—occlude this damaging reality. Much like the jaw tension that accompanies staring at a laptop all day is classed as a “referred pain,” the discipline of ergonomics is a way of re-routing the harms wrought by the transition into neoliberalism. The Aeron and its associated design solutions mask the fact that the problems of past regimes of labor persist into post-Fordism more acutely than first impressions would suggest. The fantasy of an ergonomic workstation plays more into the lust for a frictionless virtual existence than it does for laborers’ lived comfort, upholding the connectionist spirit of contemporary networked capitalism in its implicit assurance that embodiment can be ignored, or at least set aside for the eight-hour workday. The underlying wage relations have barely changed, their cruelty only amplified to meet the demands of the digital economy. “Desk neck,” then, is not an individual pathology to be solved by a laptop riser or comfortable chair—it is a reminder of our shared responsibility to shoulder the burden, a resurgence of all the cruelties repressed by ergonomics’ appeal to comfort.