An androgynous figure walks the woods in the near-dark, blindfolded. Thick white cream cotton, uncertain and… followed. Stretch their elbows out, forward and down. Brush up against each other gently, limbs. The branches snap underfoot and roof overhead into green leaves gone grey with the dark and are dried up on the ground, wrinkled. Unseen but not lost. Unknown but not placeless. Feeling fallen behind but catching up again, again.

Summer nighttime bug shimmer, but perhaps it is only the woods and a temporary portal between two trees passing, whispering a limp wind direction, and lifting their feet into the force of it, seedless night. These people pass over the moisture of the soil saying that the sound of water could be the sound of passing cars, but here there are roots holding the ground in place, here there are stones held inside the ground, here they are pausing to look around, sightless.

I am watching Olivia Boudreau’s “L’obscurité / Obscurity” (2018) (video, 5 min 48 sec) alongside two other video works, and looking at documentation from her exhibition "Scenes and Sequences" at the Galerie d’art Louise-et-Reuben-Cohen. Considering these works all together, the low insect hum of “Obscurity” pools underneath everything, and the sound of footsteps is both steady and wavering, riddled with pauses. In these works, I see the frailty, uncertainty, and incoherence of my own life reflected back at me. I feel deeply comforted by these works, and in my conversation with Olivia she describes this phenomenon as “(her) psyche reaching out to meet the viewer’s psyche, and together they’re doing something.” I like how she wants to leave space for the viewer inside of her work, to be conscious of sharing space. It makes sense to me that meaning-making happens at some unknown point between bodies.

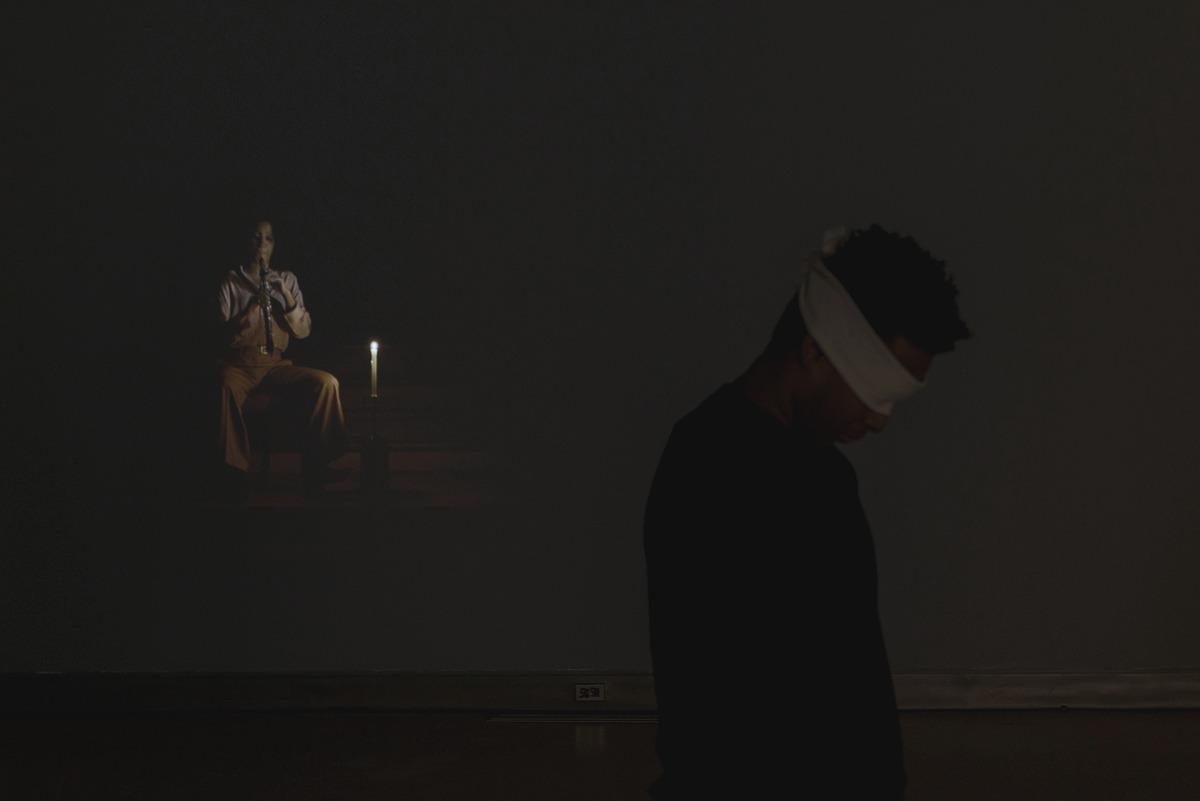

“Obscurity”’s choreography is mirrored by a loosely-scripted performance, scheduled every Saturday for the run of the exhibition, wherein a blindfolded figure moves slowly between the rooms, instructed to use the sounds from the show to orient themselves in space. A second performer trails them, keeping a certain distance and remaining discreet. Like the video, the gallery itself is quite dark: a few circles of light for each of the written works, and a dim, reflected light cast by the projections. I feel a silence in this darkness, an unseeing, which is repeated again in “Le retrait / The Withdrawal” (2018) (video, 53 min 23 sec). Here comedian and oboist Florence Blain-Mbaye sits in a dark room, in a pool of light for nearly an hour. She plays J.S. Bach’s aria “Erbarme dich” (“have mercy”) over and over again, gradually replacing each note with a measured silence until finally the room is emptied of sound.

“Le retrait / The Withdrawal” (2018) in the exhibition Scenes and Sequences”

Having spent a lot of time with my elderly grandmother these last few years, I am feeling the smallness of my own life in a different way, and seeing how our intimate architectures are subject to decay—our homes, our minds, our memories. As I watch “Il faut tomber / It is necessary to fall” (2016) (video, 13 min ) I am reminded of something my grandmother had said to me once, she said, “sometimes I would give them everything, and there would be nothing left for me.”

In the video, children rush forward, crowding around a woman who lies on the ground dressed in blue. Each child takes a turn to whisper a story in the woman’s ear, and as she lies there like an empty vessel, she paraphrases each story in turn, repeating back the parts she can remember. These stories are about falling off horses, written by Olivia after her interviews with equestrian riders, and the woman is actress Sophie Cadieux. She stares blankly forward, looking past the camera. Her eyes well up with tears.

“Should I say that these works happened when my mother was losing her memory?” Olivia asks, and explains her question by saying, “Ten years ago I wouldn't have said that, even though all the works I’ve done before contain part of my own memories, and… very intimate experiences.” As she tries to describe what else has changed for her, in creating this series of works, she says, “I wanted to reveal myself a little bit more clearly, and… I wanted to feel comfortable with beauty, with emotion. Right now I’m saying “emotion” and putting those two little guillemets around it. I’m still feeling very uncomfortable to say the word—emotion—in the purview of contemporary art.”

One of two written pieces in the exhibition—“La Lettre / The Letter”—is an excerpt from a letter written by her father about her mother. At one point, she says, she knew this passage of the letter by heart. The text is written directly on the gallery wall and is so heavily layered as to be largely illegible, though words like “elle” (she) and “hospitalisée” (hospitalized) show through.