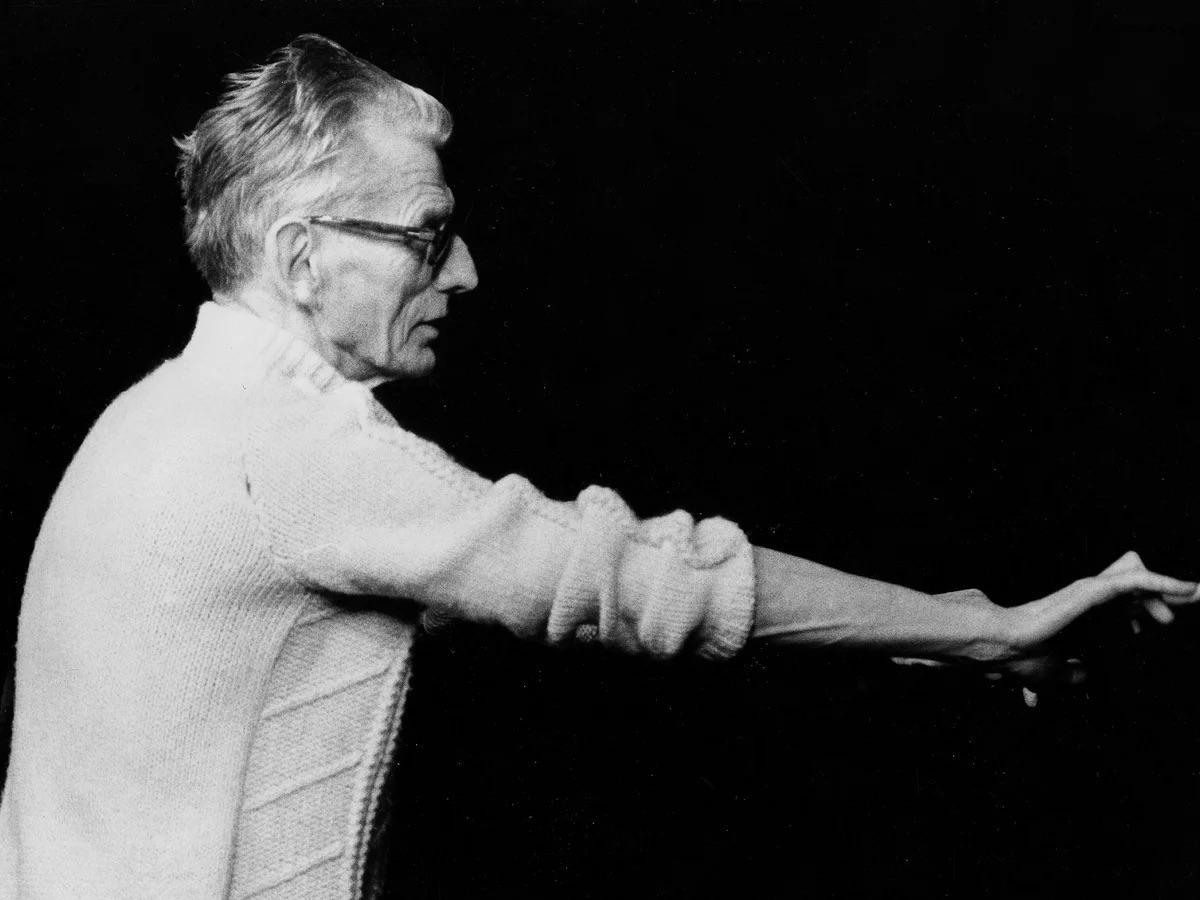

Samuel Beckett, 1977. Sourced via.

I want to stop thinking about myself. In fact, I wish I could lose my “self” completely. Not for lack of will to live, though. Quite the opposite. I sense with greater frequency that my “self” gets in the way of living, or, is the focus of an inhospitable pressure. It was an unexpected realization, in part because, at present, the need for self-actualization—the pinnacle in Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs”—has become an effigy of Western pop-psychology. With a puzzling degree of certainty, we generally seem to believe in an “authentic self.” It’s this version of the self—not the one you presently are—that’s capable of expressing and utilizing its full creative potential. This actualized form presides like a spectre over our lives, omnipresent since birth, and perpetually out of reach. Art and politics function as modes of symbolic representation within this schema. They present a multitude of techniques to make the self visible to one’s self and to others. These mediums give the self a tangible form and aid in its continual management. The most common notions of selfhood depend on the legibility that art and politics provide, enabling a sense of security in an unstable world. Today, as people’s ability to meet Maslow’s lower needs (food, shelter, and loving connection) are strained by the pressures of late-capitalism, an inversion has occurred. The hierarchy has flipped. Somehow—though I have my suspicions—self-actualization has become the skeleton key to basic survival.

My thinking is this: the distinction between creative potential and economic value has collapsed. Meaning: the self of one’s creative potential, and its concurrent authentic expression, is a commodity. Actualization is merely the labor needed to produce it. Much like other commodities, this one doesn’t belong to you either.

The contemporary literary landscape is a digital paper-trail of people’s obsessive efforts to achieve this actualized form. The increasingly self-published literary market is dominated by memoirs of self-discovery, glib auto-fictionalizations, and the ballooning genre of self-improvement in which writers mine their personal lives to proliferate public personas. Cultural theorist Anna Kornbluh terms this a literature of “auto-emmission.” Immersed in this super-genre, one finds certain stylistic conventions. These craft elements have the cumulative effect of closing the gap between the narrative self and the “real” one. By conflating these selves, this literature performs an aesthetic self-actualization. In this essay, I’ll prod at this aesthetic impulse to ask who exactly profits from its reiteration. I suspect the answer is actors just outside the narrative frame.

The liberal self of modern day politics, stripped of literary stylization, makes its ambivalence unbearably clear. In the US and other nations like it, forms of legitimate government identification and enfranchisement only grant tentative access to social welfare and legal protections that are always subject to revocation. The enforced representation of selfhood via impersonal legal documentation renders complex persons inhabiting mutable identities into fixed and readily legible subjects. Within existing political infrastructures, this enables government agencies to perform sanctioned murder, maiming, and abduction with precision. It’s a grim way to apprehend the state of things, but in this disenchantment, we can see liberal selfhood for what it is: just an ambivalent condition we’re resigned to, a co-existent variable of our survival and our death.

Recent headlines in the US involving several self-immolations are poignant manifestations of this ambivalence. It may be impossible to speak sufficiently and appropriately of the suffering of the pro-Palestinian activist, Aaron Bushnell, and the prisoners of Virginia’s Red Onion super-max security facility, Ekong Eshiet and Trayvon Brown. However, their immolations provide sobering examples of how effective self-annihilation—not actualization—can be. Without reducing the unbearable suffering latent in these acts to mere metaphor, I wonder, could a similar, though distinctly abstract, tactic be used to resist the market-driven pressure to self-actualize through literature?

The self that is actualized, its aestheticized persona, your personal histories—to publishers, tech companies, and ailing readers desperate for their own transformation—this is your value. But as it turns out, your value isn’t even yours to profit from.

PART ONE

“You already contain everything you need.” For such a reductive phrase, it’s a highly lucrative one. Think of the countless self-help books, online influencers, and wellness industries that monetize it. Each one promises that their technique for optimization will introduce you to your “real self,” and this alone will put an end to your suffering. Yet time after time, the program falls short. It’s on to the next one, with no shortage of new titles, authors, and their corresponding modalities, until you’re hospitalized for exhaustion. Even when you decide to turn away from the self-help section entirely, it's there, ready and waiting in another genre.

In Immediacy, Or The Style of Too-Late Capitalism (Verso, 2024), Anna Kornbluh is keen to identify a chilling correlation:

The monetary profit many authors earn from self-help (not only in book sales but in banquet speaking and retreat leading) would seem to contrast with the elusive benefit to the average consumer, since the reams of positive-thinking and personal-empowerment literature have coincided with rising suicide rates, epidemic drug addiction, a $15-billion-per-year psycho-emotional pharmaceutical market, declining life expectancy, and exponentially expanding consumer, household, medical, and education debt.

As she points out, our general well-being and material conditions continue to degrade beyond livability, making us the target audience for a growing list of titles instructing how to help ourselves. Korbluh further argues that over the last several decades, the big business of self-help has embedded itself in other genres too. The idiom “you already contain everything you need” can be felt working across genres such as memoir, fiction, and critical theory, amassing into a blur that Korbluh calls, “auto-emission.” It can be characterized, loosely, as drawing on the author’s biography and experience to reproduce their lives—and their self—authentically. Its genre conventions are first-person narration, present tense, and an emphasis on the mundane. Instead of a fictional plot, the author’s real problems get worked out. In place of characters, there are real people. The stakes for the autofictional literary project, those are real too. Auto-emission is invested in authenticity beyond mere realistic representation, aiming not just to represent the self but to create it, and make it concrete.

Far from authenticity’s promises of free-unencumbered-expression or totally assured solidity, auto-emission results in a style of writing that draws the self, along with the pressures that liberal selfhood imposes, to a smothering proximity. Take the writer, New York City socialite, and minor-actor, Ivy Wolk’s recent Substack newsletter, for example. The first half recounts a hangover-induced sex dream in focused cinematic detail before abruptly admitting, “I find these fantasies to be so embarrassing, so fucking embarrassing, but the one stroke of relief I get from them is the fastly fading gratitude that no one can read my mind.” Earlier in the post she effuses:

One boy took the form of Real Me’s sixth grade crush, a towhead blonde who moved away to Central California before high school, and the other boy appeared as the dark-haired older roommate of a Real World friend of mine. Real Me finds this combo surprising, but Dream Me said the three of us were very close friends. Dream Me felt really guilty about the whole thing, wanted to ask them if it was okay, wanted to apologize, waited for them to tell me that it was weird and gross and that this wasn’t something the three of us did with each other, and that it surely wasn’t something that anyone should ever do with a girl like me at all.

Wolk’s immersive ruminations emit without interruption or narrative distance. Right away, this can be interpreted as autofiction or a personal essay, the conventional forms for a Substack post. Her use of close-first person narration, the “I” dispensed with an overly self-aware, overly stylized stream-of-consciousness, produces an immersive experience of an aestheticized self. It reads like Wolk is gaseously filling a room, populating it with perverse twins, supposedly different versions of herself that are actually identical to the real one. All of its formal elements seem to contribute to a cloying concrete self-mythologization. It produces a version of Wolk that poses as authentic, encouraging a sense of intimacy between us and her. She’s completely aware of this one-sided intimacy as she narrates her own one-sided psychic relationships. It puts her personal voice, raw, relaxed, and completely self-aware on full display. With writing like hers, personal voice is often the main attraction, and sometimes the only one.

Once you start looking, it’s not hard to find. This style of aesthetic self-reproduction is almost compulsory. But why, all across genres of a rapidly shuttering publishing industry, is contemporary literature the medium where real selves are actualized, made authentic, more concretely real? Kornbluh offers a compelling answer. She connects the genre of auto-emission to the economic precarity of the publishing industry, in which, like other careers in arts, the prospect of “making it” is withering. She writes, “Absent institutions like writers’ guilds and staff unions, absent salaries for hours on background, absent knowledge protocols like investigative reporting or long-form synthesis, and drowning in student-loan debt, content creators wield their only asset: expression of their inner life.” The self that is actualized, its aestheticized persona, your personal histories—to publishers, tech companies, and ailing readers desperate for their own transformation—this is your value. But as it turns out, your value isn’t even yours to profit from.

Substack, as a self-publishing tech-corporation, is seeing massive growth in active subscribing users, and the dollars they rake in. Established and not, writers have flocked to Substack where they can expediently churn out pay-walled content mined from their personal lives. Miranda July has one where, behind a paywall of course, readers can hear about her latest obsession with an eastern European Etsy seller and the nudes she sends her friends. So does Tao Lin, Sean Thor Conroe, Mary Gaitskill. Consisting of recent or discarded material, their subscribers not only get access to the latest work but also the sensation of occupying the real-lives of their favorite writers. But it’s also likely your best friend has one. Your professor. Maybe you do too. Like other forms of social media, Substack is where writers can build an audience before there’s even a book to promote. This is something that publishers specifically look for as they need their own assurances that authors will be able to sell books. From the “big five” American presses to the thousands of independent ones, all publishers want to sell books, and the risk of finding an audience is cut dramatically—as are the cost and labor of a PR campaign—if the author is already a micro-celebrity or an influencer with a loyal fanbase. (For more on the specific operations of a wide array of American publishers, author and co-editor of the small-press Fonograf Editions, Jeff Alessandrelli gives a thorough survey in this essay.) As one is now expected to have social media, preferably with an impressive presence, to be considered a competitive applicant for jobs, grants, schools, and the like, the same expectations fall on aspiring writers, established ones, and those just trying to tread water. Constant self-promotion is required whether you are trying to “make it” or you already have. Livelihoods hang in the balance of an atom-thin margin.

The self tempts us with stable form and authentic expression, which seems inherent to our being most of the time, then completely fabricated, a farce in the face of ordinary crises.

PART TWO

Chalk it up to brain-chemistry, philosophical orientation, or socio-economic background, it either is or isn’t surprising that in response to the unbearable pressures of late-capitalism, many have opted-out with whatever means available. Speaking for myself, taking such action is completely cogent. It could be a genetic predisposition to suicidality, a symptom of early-childhood development, or a particular sensitivity to the general state of affairs. Whatever it is, when I learned there were five known political self-immolations that took place in the United States in the year of 2024 alone, no, I was not surprised in the least.

On February 25, four months after October 7, which marked an escalation of the decades-long Israeli occupation and genocide of the Palestinian people, 25-year-old Aaron Bushnell set himself on fire as he spoke his last words, “Free Palestine,” through a dense blaze. In one retelling of the self-produced footage, Bushnell “props up his cell phone on the pavement, pours some flammable liquid over his head, pulls his cap down, and flicks a lighter on around his ankles,” in front of the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C. He broadcasted it on a Twitch livestream in an attempt to reach as many people as possible, correctly anticipating that American media would attempt to suppress it or urge its circulation to pass quickly. Stills of the livestream populated my fraction of the internet for several days. These posts heralded Bushnell as a martyr and a modern saint. I was inclined to believe them. Other pockets online characterized Bushnell’s act more cynically as depraved attention grabbing, centering himself in a genocide that had nothing to do with him. Elsewhere, a report claimed that his friends, while they were aware that Bushnell was steadfast in leftist politics and identified as an anarchist who “believed in the abolition of all hierarchical power structures,” were caught entirely by surprise. At the time, Bushnell was serving in the United States Air Force. It’s a contradiction in his biography, in my mind, that fails to adhere to a coherent narrative line or assimilate into making sense.

More self-immolations followed, this time seemingly in response to the United States’s carceral system. On September 15, Trayvon Brown and Ekong Eshiet ignited themselves on fire while in solitary confinement, attempting to find relief from the unlivable conditions inside Virginia’s Red Onion State Prison. In their explanation, they cite habitual virulent racism at the will of white prison guards. These were part of a succession of twelve similar self-immolations, all of which were by black men, carried out within a span of several weeks in the super max security facility. Kevin “Rashid” Johsnon, a reporter currently incarcerated at Red Onion who has himself performed a 71-day long hunger-strike to protest these conditions, had written articles about several of the men who immolated, and the otherwise unspoken of abuses they suffered inside Red Onion. Johnson reports that Eshiet was adamant, recounting the events while receiving treatment for his severe burns, that the string of self-immolations “were not protests […] but acts of desperation, hoping to get out of an insufferable situation.” How are we to interpret the situation given Eshiet’s testimony? Even as reporters or the actors themselves attribute their acts of self-annihilation explicitly to either political or personal motivations, the act itself defies stable interpretation.

In The Suicide Archive: Reading Resistance in the Wake of French Empire (Duke University Press, 2024) Doyle D. Calhoun argues that suicide, or self-annihilation, can be interpreted as resistance in two ways: political and semantic. First, Calhoun argues that all suicides and suicidal tendencies are political insofar as they are a “refusal of the world as it is currently structured,” when read through an extended history of postcolonial resistance. As settler colonialism, anti-Blackness, and capitalism are intimately intertwined, today we could also read suicide as a refusal of life under late-capitalism. The second interpretation explains the “power and precarity” of suicide as not just a political act, but a form of political speech. This recalls Gayatri Spivak’s canonical post-colonial studies essay, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In it, she argues that ideological production in the West and forces of capitalist globalization render it impossible for the subaltern to speak for itself. The Indian practice of “sati” or widow self-immolation figures in the essay as an ordinary activity and an extreme case study of subaltern speech. For female colonial subjects who, according to Spivak, can never speak legibly to their condition in their own terms, sati and other forms of suicide are understood as a means of articulating the unspeakable. Spivak’s example is meant to demonstrate her point in extremis: the subaltern is always already incapable of legibility as a liberal subject, or a self, under the conditions of Western epistemology and capitalist globalization. Subaltern suicide, then, is an extreme case and an exception to the rule. As Spivak and Calhoun understand it, literal self-annihilation can be read as an otherwise impossible form of subaltern speech, a pronouncement of agency, and an escape from unbearable conditions.

Let’s recall Eshiet’s testimony. Calhoun’s double-valent understanding of suicide as resistance is crucial to hear what Eshiet is saying. Despite the raw availability to be read as a protest against state-sanctioned racial terror, Eshiet resists this impersonal and conclusive interpretation. He insists on personal relief from the unbearable. One framework on its own is insufficient in registering the individual anguish of each prisoner who sought relief with what little means were available. It contains both political and personal dimensions, as well as others we’re not likely to ever know. The gaps in what can be known or given a narrative about suicidal behaviors is where the resistance to interpretation resides. To read the self-immolations of Red Onion prison and Aaron Bushnell next to each other, the force of self-annihilation, not just as a physical act but a rhetorical one, comes into focus.

Maybe to practice self-annihilation now isn’t about surrendering the “I” over to a divine power, but taking a form of narrative power back.

PART THREE

One could say that Calhoun’s methodology is a-typical for a historian. Throughout The Suicide Archive, Calhoun uses literary objects as his historical archive, such as novels, films, and oral storytelling traditions that contain connections to actual suicides. In Calhoun’s theorization, aesthetic forms are particularly adept at leaving room for multiple or contradictory interpretations in a way that news clippings and other forms of archival documentation don’t. As Calhoun states in the introduction, “The Suicide Archive explores how aesthetic works give shape to the untransmissible and unsayable: the resistance of the subaltern who speaks through dying,” effectively responding to Spivak’s “Can the Subaltern Speak?” with, “Yes, and.” I sense other possibilities for writing along this line of thinking. In reading The Suicide Archive alongside the literature of today—which operates at the other end of this representational register by reproducing living selves and making them more real—could it then also be used to annihilate them? In other words, just as literature can generatively unsettle confining narratives of the dead to resist their political or cultural cooptation, can they do the same for the living?

It’s possible to say that Simone Weil attempted this feat in her life through both her intellectual and political endeavors. Before she died in her thirties, possibly of complications from a hunger strike, the classics scholar, mystic, and extreme leftist produced notebooks that would later be edited into the compendium, Gravity and Grace (1947). In their pages, Weil proclaimed everything material that we cling to, including our bodies, could be stripped away in an instant. The only thing we ever truly possess is “the power to say ‘I.’” Or, echoing Korbluh, to express our inner life. Weil was determined to give the power to say “I” up to God, believing the self to be a barrier between the divine beauty of the world. Read in a secular context, this could simply mean that the self is a tender ruse, a delusion of wholeness, posing as a way out of suffering while leading us to it. The self tempts us with stable form and authentic expression, which seems inherent to our being most of the time, then completely fabricated, a farce in the face of ordinary crises. Weil’s writings come from a time of post-war property booms, of growing suburbs and low mortgage rates for veterans in the 1940s, but today, fewer and fewer individuals are capable of owning anything outright, not even their self-expression. Maybe to practice self-annihilation now isn’t about surrendering the “I” over to a divine power, but taking a form of narrative power back.

What I want to do by bringing market-driven narrative self-actualization into tenuous relation with the self-immolations of the past year, is to propose, cautiously, a style of writing that resists the asphyxiating pressure of late-capitalism and provides a temporary source of relief. The late theorist and literary critic, Lauren Berlant, took interest in this speculative style too. In an essay titled, “On Being In Life Without Wanting the World,” Berlant considers a mode of writing and living with suicidal ideation. Berlant terms this, “dissociative poetics.” Through various literary examples, such as A Single Man (dir. Tom Ford, 2009) and Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric (2004), Berlant observes how particular narrators navigate ambivalent attachments to biopolitical structures, identity, and personal history, in ways that passive bystanders would pathologize as suicidal. But Berlant is careful to emphasize that for these narrators, and real people alike, contemplating self-annihilation isn’t merely a stop on the way to suicide, contrarily, the psychic dissociation from the world can provide just enough mental distance to take a beat, to process, to slowly recover, and otherwise enable a person to keep living alongside debilitating necropolitical structures. Whether or not suicidality is named by the author, the practice of writing itself can be a form of dissociation. Within the aesthetically mediated suspension of the self, the language of craft allows both writer and reader to enter “narrative gaps” where the crisis of selfhood can be maneuvered long enough to provide relief from the wearing out activity of self-actualization, and politically resist the demands of legibility.

Berlant makes a compelling argument for what a style written in a manner of self-annihilation could do. Still, I wonder about all the ways it could look and sound, along with what specific effects its various permutations could enact. Perhaps contradictorily, this style would write the self in all we’d expect from Kornbluh’s diagnostic traits of “auto-emission,” implementing first-person narration, present tense, and the author’s autobiographical memory. It would do all this but with a pointed perversion. Take Samuel Beckett’s novella, Company (1989) for instance. The narrative depicts an old man in a dark room accompanied only by a disembodied voice that troubles his ability to narrate and know himself. Rather than seek assurance of the self’s existence through stabilizing measures, Beckett’s narrator leans into the embarrassment the voice creates. Embarrassment marks a perceived gap between the self of one’s social obligations and an embodied present. This lean into lower registers can be seen in grammatically disjointed digressions in which the narrator considers altering his physical position in the dark room: “In the same dark as his creature or in another not yet imagined. Nor in what position. Whether standing or sitting or lying in some other position in the dark.” He does not imagine standing or leaving the room. He entertains only going lower, towards more embarrassing postures: “Crawling on all fours. Another in another dark or in the same crawling on all fours devising it all for company. The possible encounters. A dead rat. What an addition to company that would be!” Here, his tone is peaked in exclamation, whether in earnest excitement or sarcasm, we can only speculate. It seems that, cleaved from a narrative self, his estranged and creaturely body is alive with a contradictory sort of reason that exists outside of the narrative self. With this reason, he responds, or adjusts, to the terror of the self’s too-closeness by drawing nearer to the ground. His language disjoints in a disorienting narrative distance from the self that also provides momentary relief. Without a life story he can claim as his own, without the ability to narrate life at all, he becomes a self-less crawling creature.

Contrary to the literature of our time, Beckett is an example of how authors of the past have written the self in order to unsettle it. Yes, Beckett renders the self, but just enough to confuse it to the point of utter illegibility. Sure, Company is maudlin in premise, but it’s proof that a style of self-annihilation need not only be droll or melancholy. It can be absurd, abject, rife with potty humour and slapstick, ceasing on the comedic mode as the most adept at skirting straightforward interpretations. In further iterations and explorations of this style, perhaps there’s room for heartbreak too. A style of this kind doesn’t shy away from the unspeakable suffering that ordinarily disorganizes our sense of the world. It’s possible that this style would be unpleasant to read. However, as Aaron Bushnell, the Red Onion self-immolations, and countless other unnamed forms of political resistance would attest, there can be immeasurable relief in the discomforting, in initiating your own annihilation with a knowing smirk.