When I started reading about Ayesha Singh’s work, I was also reflecting on utopia in relation to localized aesthetics and ‘global’ migrations. I had just visited Jonas Meskas’ posthumous exhibition, Let me dream utopias, at Rupert in Vilnius and circled in the exhibition essay: “‘Real utopias,’ Mekas claimed, ‘may only be found within one’s small closed village evoked with the specific mouth muscles of one’s mother’s tongue.’” In our interview, Singh and I never got around to asking each other the name of our ancestral village, but I think (and I hope) we felt the pulse of the ghost muscle linking her art practice with my own critical/ curatorial inquiry. Ghost muscle, to say something of our tongues’ twisted, even if no longer taut, entwinement with the colonizer’s language. We spoke about art in English (and extensively) but we delivered our jokes and glances in Punjabi/Hindi. Like our parents, we lived in the tight corset of British Colonialism and post-colonialism, but the digitality of our connection helped us to take in more air, across oceans and borders. Again, a hope on my part to see a more global and connected world than I inherited.

Born and raised in India, Ayesha Singh left New Delhi to complete her BFA at the Slade School in London and her MFA at the Art Institute of Chicago. Naturally, the encounter between a South Asian and British visual culture was not always a clairvoyant one, as it became apparent when one of her professors questioned her about the relevance of postcolonial critique in contemporary art from the region. The relevance… of … postcolonial critique. This and other jokes emerged out of my interview with Singh, which unfolded at her recent solo exhibition at Shrine Empire Gallery in New Delhi. The exhibition contained new work, divided up into five overlapping series: Hybrid Amalgamations, Hybrid Fragments, Frayed Continuum Pendulum, Capital Formation (Projection), and Capital Formation/No Exit Nation. Singh’s past and impressive education in both London and Chicago figured into our conversation through anecdotes and afterthoughts, but what pushed to the forefront was a comfortable and comforting hospitality, as if knowing this was only the first of many conversations. Because it had to be, if not for the weak Whatsapp reception and low battery (mine) then for the lingering promise of a deeper, longer engagement.

The following interview is the result of an early morning/midnight conversation between Singh and myself, which revolves around a tour of her exhibition, It was Never Concrete at Shrine Empire. We discussed the public and conceptual threads in the exhibition, circling questions of cultural multiplicity and the ensuing violence of hybridity as they have unravelled through the contemporary architecture of India. And, you know, even when Mekas’ wrote about his desire to find the future in his own village, utopia was never concrete. It was designed to fail, in many ways, And so, was my conversation with Singh: it ended too soon and I wished to be in the space with her, peering into the details of her carefully rendered drawings – like perfect printed images – and I wish I was there too, watching her ornaments wrestle and crash into each other. Then, to bend over and smell the scent of chipped wood in an air-conditioned room. But that close vision and the immersion in the sound and scent will come, another day.

i wouldn’t say hybridity is a post-colonial phenomenon. Though, yes, in a time of puritan politics it feels important to have works that reinforce the undeniable evidences of the layering of cultures and multiplicity we embody.

Before we start the tour and thinking about some of the key themes in your work, could you tell me what is included in the exhibition at Shrine Empire? And, perhaps, some of your reasoning behind putting all this work together?

Colonial histories, the continuation of the creation of post-colonial hierarchies, the movement of cultures through the migration of peoples, and its physical evidences in the way a city is constructed - I have been looking at the way we view these narratives and carry value-systems forward through architecture, and how it shapes the way power is perceived. As an interdisciplinary artist, I use various media to go deeper and push the concepts and ideas the works explore, this exhibition puts together four of those explorations, creating a base introduction of my practice to its Delhi audience. The works installed here are- Hybrid Amalgamations, Hybrid Fragments, Frayed Continuum Pendulum and Capital Formation (Projection).

Hybrid Amalgamations references parts of Delhi’s architectures that present and layer histories through fragments of ornamentation from structures that are considered to be monuments of the past. For example, there is one work that has a part of the Red Fort (constructed in 1639 by the fifth Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan); a fragment of the steps at Jantar Mantar (commission completed in 1724, by Rajput Ruler Maharaja Jai Singh) and India Gate (made in 1931, designed by Edwin Lutyens, when we were colonized.)

The exhibition begins with work that references architecture, to that which brings actual fragments of buildings and their coexistence into the gallery space, and the last work, Capital Formation, takes the audience to the crux of the content that the earlier works refer to or hint at.

Hybrid Amalgamations, Graphite and pencil on paper 24 x 18 inches, 2019

I followed the opening of your exhibition through Instagram and saw some of the images of your work. In one, there is a reference to the columns in Connaught Place in Delhi. I haven’t been able to see all the details of this work, but I get the sense that, overall, this body of work is an active assemblage of contemporary India, brought together from remnants of local and colonial architecture.

Yeah, the exhibition is contextualized to Delhi’s architecture and the history of movement of people, cultures, ornaments, techniques and the resultant spaces that they occupy or create- including Mughul, Rajput, Indo-Saracenic, modern and contemporary forms. There is this objectivity that comes in when you move away or feel displaced from the place you grew up in. I completed my BFA in London and then MFA in Chicago, so a lot of the work was informed from that experience.

The Hybrid Amalgamations almost look like collages when viewed online, but they are actual drawings? They look very realistic.

Yes, they’re graphite on paper. My hand works nearly like a printer - creating dots that form an image, it’s a very slow process!

And like a printed image, are the visual elements easily recognizable by the audience? Or do you have to explain?

Not all of them. Indeed, some elements are very easy to recognize, like with the Hall of Nations, Pragati Maidan, that was destroyed in 2017 which was quite an emotional moment for the city because it was done by the government without any warning in a way or public conversation around it, but the media covered this and the sentiment around it. Akin to the present conversation around the destruction of parts of the Rashtrapati Bhavan, people are signing petitions but there has been no response from the government in light of public reaction.

Some of the drawings refer to spaces that we as citizens of this country and people who recognize themselves as residents of this city cannot freely enter. There are newly made walls or ropes and guards at spaces in Jantar Mantar, same with spaces in the Red Fort, and then there are those, like the Hall of Nations, that no longer exist. Some of the drawings are so fragmented that they become unrecognizable.

There seem to be a lot of hybrid and anticipatory forms in your work. Do you take hybridity as a post-colonial phenomenon? Something you use as a contemporary artist to comment on the fractures and also the multiplicity of India?

I wouldn’t say hybridity is a post-colonial phenomenon. Though, yes, in a time of puritan politics it feels important to have works that reinforce the undeniable evidences of the layering of cultures and multiplicity we embody.

Frayed Continuum, Delhi, Steel, wood, DC motor, Arduino, , Discarded architectural ornaments purchased in New Delhi, 108 x 144 x 60 inches, (12)

Can you tell me about a piece that engages, or like you said, reinforces this multiplicity?

Frayed Continuum, has one element that has traditional ornamentation on it, and the other references the global-"western" ideal that comes into ornamentation in India, post-colonization. Both are hanging on a pendulum mechanism, where they rotate freely on their own axis and via the movement coded into the motors. Due to the way gravity acts upon its mass, they have moments of interaction and collisions that alter them which results in a residue accumulating through the exhibition, onto the floor of the piece.

Where did you find these ornaments?

Both are discarded fragments that were purchased in Delhi, but they’re not exactly from the city itself. They were brought into the city through salvage stores and used to be brackets used between the wall and ceiling, now being sold as sculpture. The ornaments re-enter the home in this process, not through its initially intended purpose, but reflects on the way architecture is inserted back into the capitalist narrative. Both pendulum movements layer and collapse time, histories through form and a resulting alteration or erasure in the present.

Moving on to photographic work, what can you tell us about this series?

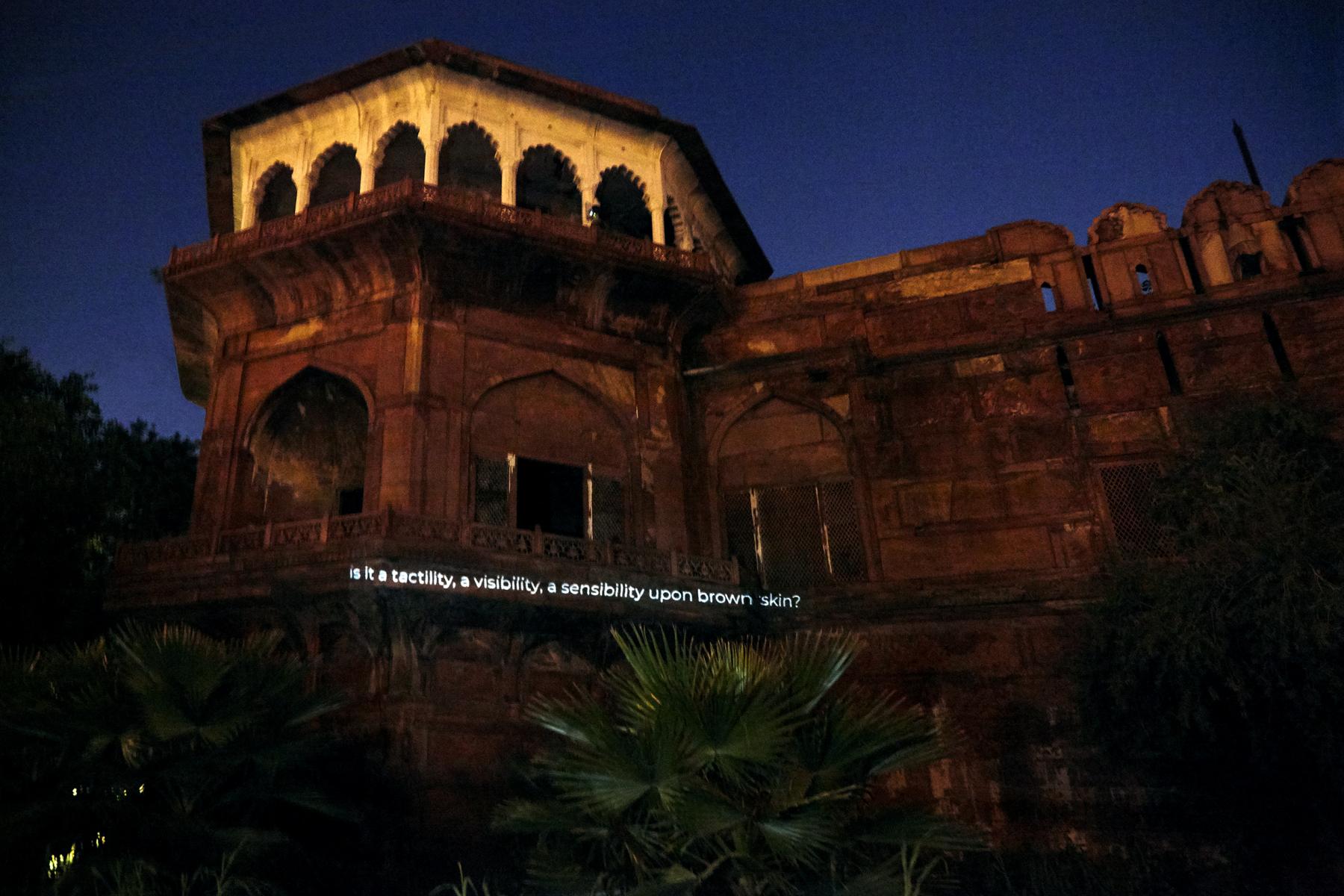

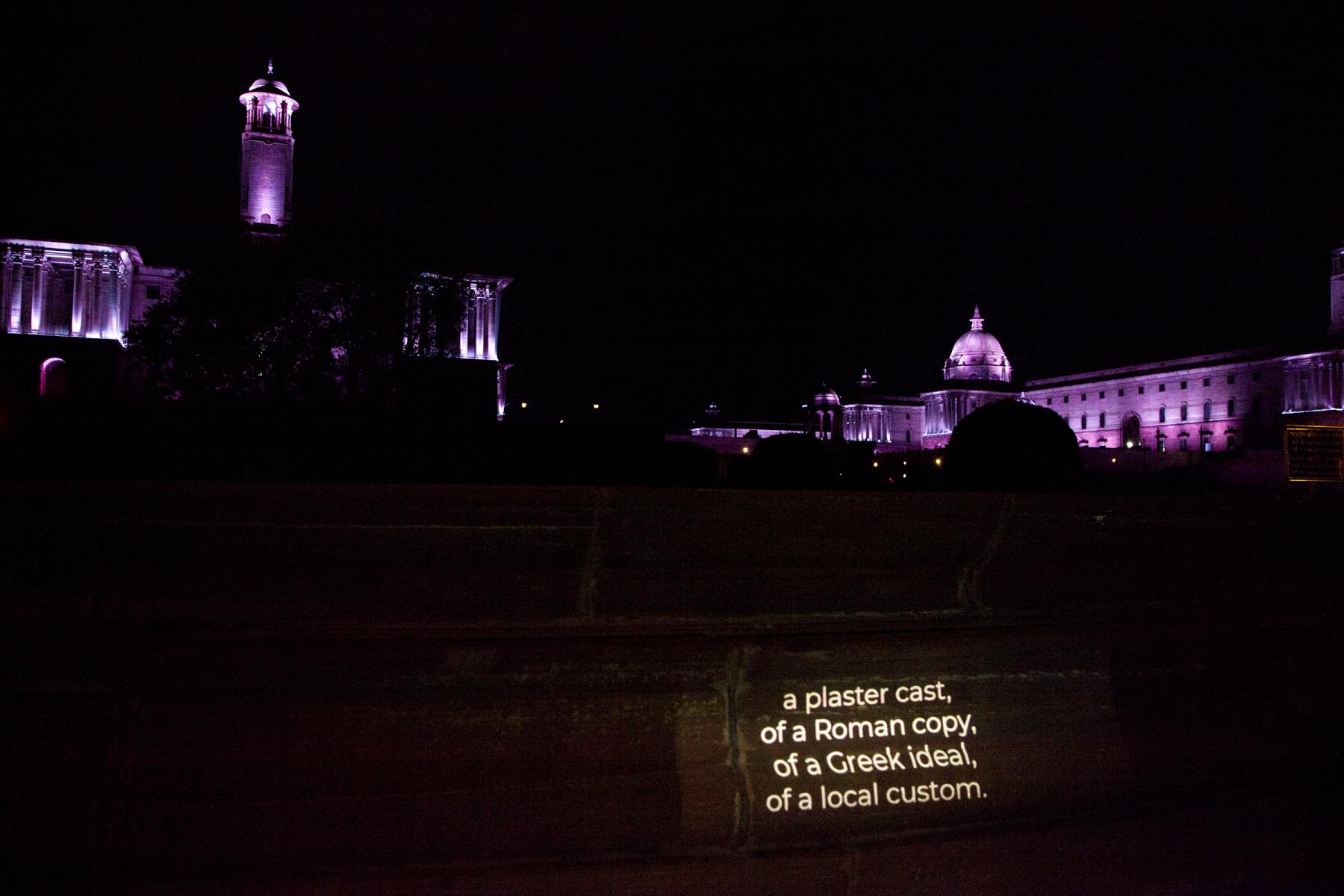

The next room has sixteen photographic works that are part of one continuous text, written in collaboration with Cat Bluemke, in Chicago, 2017. Under the umbrella title “Capital Formation”, we had created a performance and video work, voice recordings and now, this work that contextualizes the content of the text to Delhi’s architectural landscape. In her performance that we had the opportunity to show in Chicago at Links Hall in 2017 and Comfort Station in 2018, Cat invites the audience to participate in a subconsciousness-raising mindfulness program bringing up conversations around cultural appropriation, capital and white guilt, in inflatable corinthian columns. After the performance, a video of my hand caressing various columns in Delhi and Chicago presents an exploration of memory and familiarity with built form- questioning the seduction of ornamentation and its appropriation as an architectural strategy. It was overlaid with a text similar to this one - though, in Chicago, it was written for a different audience. The text questions my place in this system, how I recognize myself, or how I’m still being othered through architecture in my own spaces.

Capital Formation, Projections, Projection of text in public spaces, Digital prints, 2017-2019

I think in this work especially, there seems to be a nice translation of the American context through the Indian one. Like, thinking about race, and caste, in India, but also capitalism and imperialism. So I’m wondering how your being in Chicago for a few years for your MFA allowed you to look at India with fresh eyes and create this new series?

Ahh, movement plays a big role in understanding these layered systems. Also in terms of the way Chicago is physically divided, that is another conversation altogether.

I think also that movement, or being an outsider in the US, and not necessarily having that position in India, how that can also open up the potential for solidarity and empathy.

Definitely, it makes me think of this image that speaks about club culture, taken outside one of Delhi’s oldest club, Gymkhana’s gate. It was started by the British when we were colonized. Gymkhana was one of the first clubs that the English had opened in Delhi, and it was a space that brown bodies could not enter (it had barred the entry of "Indians and dogs" during the Raj,) and now it’s turned into a space that still maintains a strict membership and dress-code policy, retaining its exclusionary position. This series brings the conversation from old historical monuments or meaning-making through architecture, to the present context of hierarchy creation and preservation. The text on it reads, “I appropriate their corinthian, they appropriate my chai.” Referring, also, to the neo-colonial late-capitalist endeavors of hierarchy creation through appropriation, a lot of which comes through in my experiences in the movement and constantly changing contexts between Chicago and Delhi.

The exhibition focuses so much on architecture, I am wondering, how else do you navigate the tension between inside and outside?

This was a question both Anushka Rajendran, who has curated this show, and I had, regarding this exhibition. We were both very aware of the gallery, the systems in which we are creating and exhibiting work… the way we are in the basement of a residential space right now, there is no signage that tells an everyday passerby that there is a gallery here, and we are in South Delhi, in a quiet neighborhood. Our audience will be people who are already a part of the arts, or those who know us well. But the exhibition is taking in ideas from all around the city. So we are asking: in what ways can we take these ideas back into the city?

That is where the ephemera comes in, we just put these out yesterday. The material is one that is used to make flyers that are usually put into newspapers in Delhi. It is a collaborative work between Jyothidas K.V. (a Delhi-based artist who is trained in printmaking, currently delving into performance work) and conceptualized with Anushka and him. We worked on the content as such that he wove a text he had earlier written titled No Exit Nation through the text present in Capital Formation. We performed this text and his poetic responses to it yesterday, and brought out the ephemera so that the visitors can pick up as many as they like and place them in spaces - either public or private - that they feel are appropriate to the content.

In the English version, you can see that difference in tone between Jyothi’s voice and Cat and mine, whereas in the Hindi and Urdu versions you can’t. And that’s because the Hindi version has been translated by one translator- one person. So, it sort of flows as one voice. The English version has its academic moments; however, the Hindi and Urdu are both written in their colloquial tones and the jargon is removed from it so that even a child can read and understand the content. For example, instead of post-truth, there’d be सच के बाद (sach ke baad.)

And how did they translate post-colonialism?

I think the translator, Ishaan Ratnam, changed that one!

Changed that one?

Too academic! [Chuckling]

And that’s the final piece in the exhibition?

Yeah, these are posters for people to take away. Once we brought the conversation into the gallery, then it sort of stays in these circles that have the language for it and understand its references. But the prompt here says: “these posters are here for the audience to carry ideas that emerge in this exhibition back to the city that informs them. Please take as many as you like and put them up in spaces either public or private that are in conversation with the text.”

The title of this is Capital Formation/ No Exit Nation. So in terms of getting people to think about ways in which hierarchy has existed in our subconscious, the way in which we subscribe to it, whether they do or not – it seeps into daily life, and if it isn’t questioned, it’s assumed as a way of life. So, these go out into the city as prompts and as poetry.

I have to ask, what’s your favourite piece in the exhibition that you feel really, really proud of, and will maybe push you for future projects?

We have been working on this exhibition for a long time, initially, I was excited by each new work made. The first three series are concepts I have worked on before…though the work I am still exploring and thinking about is Capital Formation, Projections. I am very interested in exploring performance and its nuances through my practice and with the new collaboration with Jyothidas.

Yesterday, a lot of people picked up these posters, I am keen to see where they end up, and what happens with them. What it means to activate the exhibition space inhabited by these installations via the body in performance, what is activated? I haven’t put myself into the work in this way before, I am keen to see what role gender plays here too.

I love these posters, please save some for me!

Unlike the rest of the exhibition, the posters seem to promote a more explicit political activity. But overall, I get the sense you use aesthetics in a very particular way to address social and political issues, like hidden scripts if you will?

I think… more than a strategy it seems like something that has evolved over time. The drawing works (on paper and in space) are earlier works that respond to and rely on a formal language that related to my earlier training. During my undergrad at the Slade, UK, when my works started to look at post-colonial theory I was asked by my professor at the time that “why are you talking about that, it was so long ago, that’s not relevant at the moment.” I was initially shut down, in a way that the work started to sort of hide its politics. Now – undoing that experience, the new works with the texts approach those assumptions. With the ornaments work, there are layers and they can be read into.

Capital Formation images and Ephemera, installation image, from "It Was Never Concrete" at Shrine Empire

I was thinking, the text in Capital Formation, Projections are very poetic, and I think for some people, that work can just end there. You do put trust in the viewer to meet you halfway, or extend the work, or make it political. It’s … very interesting, “post-colonialism, post-truth, post-language”… people have the agency to read and then walk away…

oh, shoot my phone’s dying…

I think this is one of the things I love to speak to people about – collaborations are so important for me in that sense, to push myself through things that otherwise might be very uncomfortable for me.

The one thing that’s really exciting is how the work changes in every context. Initially, I used to fight it, but the whole idea about it is to be contextual, it has to be about the space it’s in and embody the conversation around it, and embrace the way it’s perceived, and so in terms of how architecture is perceived – let that come through.

The final work, which you see now, the fact that they are photographs of real-time projections on actual architecture around the city, is definitely influenced by the context of New Delhi and the way aesthetics are used in this context rather than what it might be – and I don’t know what the work would be like – if I was in another city. But I know it would be different.

I think that’s what I was asking with the ornament as well. Because for me, it's such a political thing, something that needs to be justified in the context I’m in. But there, it’s just an entry point into meeting where people are, and having a conversation, which is exciting.

[phone beeps] I think your battery is low…