Photo by Ananna Rafa and Jennifer Qu

“The best place I can imagine my work is at a party,” says Lan “Florence” Yee in a video introducing their recently exhibited textile series, Tangerine, After Grapefruit. Borrowing from Yoko Ono’s 1964 artist book, Grapefruit, Yee’s large format rendition takes nine 5x5 linen sheets in which hand-embroidered instructions ask the viewer to perform several curious prompts like “Sigh in at least seven different tones” and “Go somewhere you’ve wanted to visit for a long time. Don’t come back.” Tangerine, After Grapefruit was also photographed, made into book form (a collaboration with Toronto-based micropress San Press), and distributed to the public during Yee’s first Toronto solo exhibition, Just Short of Everything, at Alliance Française between January 13th to February 4th, 2023.

The first time Yee told me about the series was towards the end of our hour-long zoom conversation almost a year ago. Most of what I recall seeing in that virtual moment were large swaths of beige-coloured cloth; Tangerine, After Grapefruit was still in its early stages. Yee unfolded a blank cloth and held it toward the screen to show me, chuckling at its size, and probably imagining what it now presents. It was exciting to see the artist in this brief yet pivotal moment of their practice, brimming with ideas and at the cusp of a new work. We had talked at length about their previous projects already—an artist for almost a decade, and still under 30 years old—Yee’s portfolio is vast and more significantly, it’s transdisciplinary. Today their oeuvre includes works across mediums—painting, ceramics, textile, photography, sculpture, new media, and other forms which, frankly, stump my attempt at categorization. Their past projects have explored themes of commemoration (ones that are intimate and personal, as well as the obnoxious and colonial kind), institutional archives and their inherent contradictions, queerness and what that looks and acts like within the Asian diaspora, and questions around labour, commodity, and more precisely what American literary critic, Sianne Ngai, calls “ugly feelings”.1

Using humour and irony as a tactic to poke at the underbelly of the daily injustices and traumas of being a body in this world, Yee makes us laugh. It’s a kind of laugh that blurts out of you too—ha! Short, reactionary, and like a much needed release. Laughter as a response to art seems almost taboo in our current hyperaware art world which has, time and time again, entertained trauma as a defining factor of an artist’s (read: racialized, queer, disabled, and all who have been thwarted to the margins for far too long) identity.

Yee is very funny. This realization only became clearer—and still remains firmly with me— throughout our conversation. Humour and irony in art is not a novel idea, yet, in these post(arguably)-pandemic times, it feels rare. It is also not uncommon for an artwork to be humorous, but when paired with irony, it’s devilish partner-in-crime, and delivered with enough conviction, it has the ability to punch you in the gut, and then leave butterflies in its wake. It’s this fluttery feeling which Yee generously leaves us with, allowing us a bit of respite and a little ease from the burdening realities we know all too well. We grasp onto this feeling, and might even find ourselves basking in it. For what it’s worth, to me, it’s a feeling close to joy.

Crediting the initial moment of their artistic pursuit to Bob Ross, a 70s icon and star of the television series Joy of Painting, we dive into the interview, where Yee, a most forgiving artist both in their practice and as a person, shares moments small, big, and random, from their life. And of course, we have a few laughs along the way.

Most of my work has either a repetition or dead end which brings it back to this desire I have for possibility and un-endings.

I’ve been following your work for a while now, since when you mostly worked in painting. Let’s start there. What was the beginning like?

Oil painting was my entryway into artmaking. During my BFA at Concordia, I was very lucky to have accidentally found a course called “Art X” which I believe at the time was one of the first interdisciplinary classes at the university. I had the opportunity to experiment with a variety of mediums, and I became more aware about what the medium(s) of a work says about its intentions. I became less interested in painting after that, but the painting I was making was self-referential, and it was always drawn from an act of copying. I was interested in reproduction, both the ways that we are taught in Western schools—focusing on the “masters” and the canon—and also as a good metaphor for cultural hegemony in general. That’s why most of my well-known paintings are from the series “Finding Myself at the Museum” (2016) which I began during the year leading up to the 150th anniversary of Confederation in Canada. There were a lot of celebratory events as well as critical discourse surrounding the anniversary. I was also living in Ottawa for part of that year and I witnessed a literal countdown clock in front of the House of Parliament—counting down to the anniversary of settler colonialism. I think most of my early paintings feature an interruption of this Group of Seven-type canon.

Finding Myself at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts IV, oil on canvas, 4’ x 5’, 2017

You have now completed several residencies, commissions, and your MFA at OCAD University. What are some themes that you were drawn to during those years?

More and more now, I’m interested in memorialization and how it fails us. One experience that sticks out to me was my 2019 residency at the Quebec Gay Archives in Montreal. During this residency, I was thinking a lot about what it even means to have a supposed “gay” archive. What does queerness do to a gay archive? What does wanting to be in an archive as a queer person of color say about this desire to be seen?

I was also thinking about the structure of the archive itself—who literally has access to it, who curated the collection, and who decides what’s “queer” enough to be inside it. Actually, I only had two visits to the archive because the residency was scheduled at a time when their office was in the middle of relocating. However, I was working with a nice cohort of twelve other artists as part of the residency and we had our final group exhibition at Never Apart in Montreal. I am still connected with many of those artists years later, and it’s touching to be thinking about these failures of collaboration together.

With that still on my mind, I also produced an embroidery series of so-called “proofs”. Adjacent to that was my MFA, during which I focused on ideas of labour through embroidery work. My thesis project was called “Work and Other Ugly feelings: Labour for Queer Cantonese Diaspora'' and it’s contextualized by common migrant stories that suggest how work is supposed to naturalize one as a citizen, make one valuable as a person, and how a person becomes legible to themselves and others through their work.

Your previous exhibition How to Give Ghosts a Sunburn includes several different series, and humor is something that you exercise quite frequently. Can you talk about the role of humor and irony in this project, and in your practice overall?

How to Give Ghosts a Sunburn was a thematic grouping and I thought it was a good descriptor for the different works that I made over a two-year span. The “Proof” series makes up a large part of this exhibition. I try to infuse much of what I do with humor, or at least an ironic tone. The title is a good indicator of my interest in futility, or the thought of impossibility. Ghosts, not having skin, cannot get sunburns. But it’s my desire to materialize things that haunt us, in order to deal with them. That’s the general ethos of how I make work…trying to give a host to these specters floating around in my life. Since most of my work is autobiographical (slightly fictionalized of course) and draws from personal experiences and anecdotes, I try not to focus on huge tragedies. I’m more interested in the trickling awkwardness. I think they relate much more to experiences of living with trauma, rather than the tragic event itself.

It’s a big responsibility for an artist to be dealing with traumatic material because it can be triggering for them and for the people viewing it, which is why I prefer not to speak directly about a traumatic event. For me, it’s about the systemic source and how we deal with the event. I find that humor is a coping mechanism that is necessary in protecting both the artist and the viewer from having to deal with carrying what was at the onset. Jumping straight to a joke—being able to reference just enough in the joke to make it understood that there was something before—and not actually talk about the specific trauma is important to me. I want to leave enough unsaid so that there isn’t this triggering event. At the same time, I also do this so that it could be relatable in many different ways. It’s helpful for me because I don’t have to pigeonhole my subject matter. I use a lot of pronouns for that reason. Instead of saying ‘my mother’, I’ll say ‘she’, or ‘him’, or ‘you’. The “you” and the “I” are kind of recurring. Although, I recently learned about the “I” Industrial complex. Apparently in the last few years, there has been a trend of autobiographical-memoir writing that is hyper-focused on this voice of the “I”—this very heart spilling, trauma-ridden, performative almost, “I”. I found that interesting.

In “Proof”, you consciously work with the photographic medium, more than you have in the past. How has photography contributed to this series?

Being an interdisciplinary artist, I am able to see the blind spots in each medium, and how another medium can possibly fill them. Because my background stems from painting, I already come in with a kind of bastardized view of how I use photography, as mostly a reference, and that already changes my relationship to it. The idea for “Proof” was taken from the traditional methods of printmaking. It also refers to graduation photos, and more specifically the proof versions that people often end up posting online. I became interested in this idea of the proof as a double entendre for evidence. Proof as in: we were here, this is this. But also, I was thinking about this idea that if a person has a proof version, it means the object is unfinished. It can’t be owned or claimed, and still requires consent to be finalized. One of my main contentions with the archive and the act of preservation in general is that there is so much missing from the photograph, for instance, yet I still have this attraction to the image, and so I wanted to manifest these contradictions and examine them more deeply.

PROOF—Chinatown Anti-Displacement Garden, hand embroidery on inkjet-printed

cotton voile, 37" x 54", 2020

PROOF—Recipe Book, hand embroidery on inkjet-printed cotton voile, 37" x 51", 2021.

Installed at the Varley Art Gallery, Elusive Desires. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid.

One of the first pieces in the “Proof” series I made depicts the Chinatown anti-displacement garden (as it used to be called) at the Chinatown Centre mall in Toronto. It was basically a pile of bricks for a long time before a Chinatown community group decided to revitalize it by getting together some folks and organizing a weekly garden club. It also doubled as a space of protest, both as a literal march that happened down Spadina Avenue before the garden opened and as a signifying space where food would be grown, and could be taken by anyone. Noone needed permission, you just went in and took what you needed. In hindsight, funnily enough, since the dissolution of the group, it’s given even more meaning to the piece as collectives who fall out because of a grab for power or contradictions within their mandates—to be an anti-gentrification collective within the arts is such a difficult thing to do already. Many of these contradictions are held within the image and beyond the image, the embroidered watermark is an obstacle to the image yet still a part of it. The rest of the “Proof” pieces all tackle a different subject matter but they all have the same idea of wanting to stand in for the object while being a kind of wall that is put in front of it.

You’ve worked with photographic material that are part of official archives, and you’ve also worked with photographs that are part of the private domestic space. What do you think are the stakes of working with personal images and ephemera?

It’s several different things. When I moved away from Montreal, where I lived for 22 years, I found myself very attached to a couple photographs that I physically removed from some photo albums at my family home. I was drawn toward their nostalgic medium and chose them quite haphazardly. Maybe there was a danger in what I was seeing. I found comfort in them, but I knew using them as a material would be dangerous if they were only thought of as a nostalgic or romanticized thing. Coming into my queerness and transness, photography and visibility, specifically hypervisibility, became very fraught concepts for me. Wanting to be seen, but knowing that the kind of visibility that would be accorded to me is a certain kind of presentation of queerness that is more desired by mainstream culture. Photographs of myself also became a lot more interesting to me, especially photographs from my childhood and the day-to-day photographs that I was taking on my phone. Funnily enough, despite the phone pictures being very low resolution, the printing I did to blow them up for my “Proof” series worked very well with translucent material. (So there was some logistical convenience to all that). The work also has a particular luminescence when light is shone through it. I worked with a technician once who only had a single light installed on a piece and it cast a shadow of the embroidered watermark. The image itself disappeared in the shadow! I was really caught by that visual metaphor. Being able to see the work, not just as a flat image, and then having the image disappear as a three-dimensional object was poignant for me. Hopefully, that’s a part that clues the viewer into looking beyond the image.

As you spoke about the thin and translucent material you used for “Proof”, I was thinking about the lightness of the object in opposition to the weight that images hold. How do you balance these stark differences in the way you navigate the world of images?

There are parts of that work that may seem more fragile, and people might handle the object more delicately or not touch it at all. Sometimes I leave white gloves next to the album in order to invite the viewer to touch the work. There is something that I find very lovely about being able to give back this abstract time of labor. That's why I also do hand embroidery work, it narrows this chasm between the time I put into the work and the time the viewer spends looking at the work. Funnily enough, that photo album is also a random object that I took from my grandmother’s basement before I left Montreal. She had a bunch of these old ready-made cardboard photo albums that have this ‘80s retro aesthetic—the wonky lettering and the funky colors—which studios would give out when you send your film to get developed.

Photo by Ananna Rafa and Jennifer Qu

Photo by Ananna Rafa and Jennifer Qu

Photo by Ananna Rafa and Jennifer Qu

I've been using those empty albums in a couple different iterations. One in particular was about six years ago when I inserted Google street view images of the villages and cities where my grandparents are from. Toisan and Hoi Ping are not places with many images online and I’ve never been there either. Our parents had told us that it wasn’t a grandiose place at all. When they had visited, the villages had very little running water, and no electricity, roads or sidewalks. All of us pictured a village in the way we think about a rural farm. I had wondered if my cousins ever thought of Googling what it looks like and none of us had. I think we were all satisfied with the image we had in our heads but when I looked it up, I found that it’s actually a regular metropolis of a million people with skyscrapers and highrises. But my peruse through Google street view was interesting because Google is not actually allowed in China. The images online are 360-degree camera views from tourists. When tourists have a 360-degree camera connected to the Internet, Google is able to geolocate the device, use the images and put it all together in a haphazard collection. Despite replacing my imagination with real pictures, I still question whether it’s a more authentic vision of their hometowns.

You have a particular flair in the way you play with words. It’s evident in the titles of your projects, as well as the text embedded in the works themselves. Can you speak about how you approach text as a significant part of your work?

Some people consider the stuff I write poetry, which is interesting. I learned about the term ‘micro poetry’ from some writers I was working with and I think that could be a descriptor for the text that I use in my work. I try to keep my text as succinct as possible to mimic the way that most art is able to be seen all at once, in order for the text to be felt all at once. If it’s read in as short of a period as possible. The only reason I refrain from calling it poetry is that I don’t think I ever read the text out loud. They feel very quiet because it’s spoken in your head. Quiet in how it’s so deadening, it ends at a pretty abrupt note. Most of my work has either a repetition or dead end which brings it back to this desire I have for possibility and un-endings.

I think I’m much less interested in using reproduction as a way of subverting canon, and now have kind of turned towards a very much more playful, conversational way of making reproduction.

A project I worked on called “Pseudo-Plaque” was a collaboration with artists Aisha Ali and Andala Ali. I met Aisha’s sister, Andala, who works in writing and literature, during our MFA. I find writing is cosmic and it was very interesting to work with someone from a literary background. We were all also stuck in this bubble of academia at the time and coincidentally all three of us had received a SSHRC grant that year. I think we were hyper-focused on who gets credited for work and how things are made singularly. At OCAD especially, we are surrounded by many monuments, like the ones on University St., and one day Aisha came across a bench with an empty plaque slot that was being prepared to be filled in. We quickly produced an aluminum engraved plaque that read ‘et al’ as in ‘and others’ to insert into the slot and it was there for a few weeks before the city took it out. We would have taken it off ourselves but we accidentally stripped the screws that we put in it and we couldn’t take it out. So we just thought “Ah, someone else’s problem!” We also tried to make some castings of the bronze piece and I’ve done some rubbing—putting a piece of paper over it and seeing the embossing come off. I gave away those embossings for free at the show. I don’t think too many people knew you could just take them and I was just like “here, a stack of paper, take!” I'm getting more and more into the idea of gifting something to the visitors.

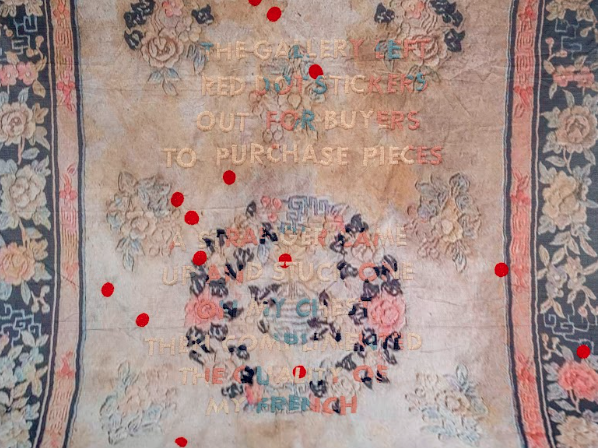

“Pseudo-Plaque” is a great example of how you’ve interrupted a space that is public, and simultaneously private, in the sense that the plaque is reserved for whoever donated money to be recognized on it. This interruption of public/private space reminds me of another work that you made called “Please Do Not Touch” where you place small red dots (which indicates that an item is sold) on a carpet and also along the white walls of the gallery space. What was the inspiration behind this work?

The original carpet was made out of thick wool. In this work, I work with the image of the carpet, but the tassels that are attached are real. The hand embroidery in the middle that I did adds volume to the piece. I try to make work that is conscious and aware of the space that it is being presented in. It was a great exercise to be able to see where the little dots could go. Some were placed on the door, one was next to the didactic text on the wall, some were on the floor, ceiling, and on other works themselves. The way I make work is through a way of seeing that is not just connected to one event, but to other events. Funnily enough, I’m also a commercial artist. I sell my work so the idea for this project comes from an experience of trying to sell art. As I mentioned earlier, I've been interested in these tiny tragic short stories about mundane things. I think the mundanity of it speaks larger than just that one story, and that’s what I think most of the dots do. They represent small stories that connect to other things.

Please do not touch, hand-embroidered thread on cotton voile print with 33

embroidered dots, 8'x4', 2021. Photo by Darren Rigo

Please do not touch, 2021. Photo by Darren Rigo

Another project that deals with the interruption of public space is the large-scale, site-specific installation you worked on for the Art in the Open Festival in Charlottetown, PEI, where you challenge a statue of John A. Macdonald, with several performance-based elements. Can you speak about the ideas behind this installation, and why you chose to respond to this monument?

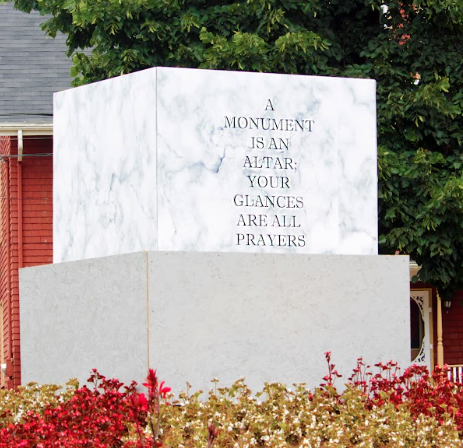

Rochford Square looks like a pristine, well-manicured lawn, and the festival thought it would do well to present work that is jarring to the space. So the first piece for this project was a pseudo-monument. I made a vinyl print of marble with the text: “A MONUMENT IS AN ALTAR // YOUR GLANCES ARE ALL PRAYERS” and I was thinking about how the idea of monumentality and statues have been in question in many countries. I was trying to encapsulate many arguments within two sentences in order to see this pseudo-monument with its false marble, serif roman font—all the signifiers of typical monumentality as a way of implicating the viewer, and to make it known that structures such as these are not something to be taken for granted. It implicates the viewer at every other monument, along with this pseudo-monument which they are figuratively praying to.

Pseudo-Monument, vinyl print on wood armature, 5’ x 5’ x 5’,

public installation at Rochford Park, PEI, 2020. Photo by Jade Misiksk.

Just a block from Rochford Square is a John A. Macdonald statue. He was the first Prime Minister and founding father of Confederate Canada, also one of the main instrumental founders of the residential school system. However, that particular statue of Macdonald is very casual, it actually seems friendly. The statue depicts him sitting on a bench that has enough space for another person, and he’s leaning in and smiling. There are many ways to respond to a monument, but because this particular monument seemed so smug, and so casual in its depiction of Macdonald, I thought it would need an equally absurd and casual way of dealing with it. With the help of the staff at Art in the Open Festival, I printed some vinyl pieces to go on a moving truck and created a fake company called “Monument Movers Inc.: Reparations and Removal”. The truck was parked next to the statue for the duration of the festival. It was all done in the summer of 2020—shortly after the June protests and the Black Lives Matter movement in particular—so the project coincided with a heightened time of questioning colonial monuments. And there had been protests at that Macdonald monument. Also, accompanying my pseudo-monument was a short 30-second radio advertisement that I recorded inviting the public to call “Monument Movers Inc.” to “get your reparations and removal”. Again, it was very much an absurd event, which implied multiple levels of reasoning such as: ‘this should be removed, it will be removed, it’s being done today’.

Monuments Movers Inc., vinyl on rented van, public installation in front of John. A MacDonald statue, PEI, 2020. Photo by Gessy Robin.

Actually, the Macdonald statue was removed in Charlottetown in 2021. I really don’t think it was me because people have been protesting its removal for years, and also because there were more graves found at former residential schools exactly around this time. There was already a lot of reconsideration around John A. MacDonald and what the monument signifies in Canadian history and in the mentality of the general public. My project specifically showed that even seemingly light and friendly parts of national memory are insidiously built into who this country protects.

You spoke about failures of collaboration and commemoration. Can you share an example of how you experimented with alternative ideas of collaboration and commemoration?

My longtime friend and artist, Arezu Salamzadeh, and I worked on a ceramic project together in 2019. We’re both Cantonese, she’s also part Iranian, and a big part of our hospitality culture is having tangerines at home, even carrying them in our purse, just in case someone needs it or you need it yourself. We thought about the offering of tangerines as standing in for a relationship that has been shared, time that has been shared. And tangerines reoccur so much in my life. It’s always something I greet other people with, or offer when I end a visit. And sometimes the tangerine peels start piling up in a corner when I have a lot of people over who also offer them. I have one friend who used to be really late all the time and would apologize and bring a tangerine. So, I see it as an alternative way of commemorating something, and maybe a performative remnant of the connection between people. It was something that we worked on very slowly during the first lockdown in 2020. We also tried to mail some clay to family and friends, because clay holds every part of touch, and every mark that’s made onto it into the material. We sent them clay with home instructions on how to make their own tangerine peels. It was supposed to be abstract and so it wasn’t supposed to be nice. They would send them back to us, so we could fire and glaze their clay peels—and so the whole exchange became another long-distance relationship.

What are some new things that are on the horizon for you?

I think I’m much less interested in using reproduction as a way of subverting canon, and now have kind of turned towards a very much more playful, conversational way of making reproduction. I’m now working on a piece that’s very derivative of Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit. It’s a book with instructional performances that she wrote when she was 29 years old. The project does also involve photography too…I can show you! I plan to make very large format embroideries that have my own instructions, and when that part is done, I’m thinking of photographing the works and printing them at the original size of Grapefruit. So I’m not sure yet, how it will all turn out but I’m very interested in these reproductions as a way of being absurd and maybe also as a kind of telephone that connects generations of artists and generations of families.

I’m most excited about an exhibition at the FOFA Gallery in Montreal that opened on April 24, 2023. It’s a university gallery where I did my undergraduate degree–a time when I held multiple anti-racism campaigns in response to systemic barriers at the institution–so it feels like a bittersweet homecoming. But the amazing part is that I got grant funding to work with Vince Rozario and Mattia Zylak on an accompanying mentorship program aimed at emerging creatives who are interested in collectivity. Knowledge-sharing and collaboration have always been the most fulfilling parts of my practice, and I hope to do even more of it in the future.