Matt and Mara, 2024 film still by Kazik Radwanski. Courtesy of Cinema Guild.

It’s a testament to Kazik Radwanski’s faculties as a cinematic storyteller that his two most emotionally resonant movies are arguably the ones in which human faces hardly appear. The seven-minute Cutaway (2014) and the 15-minute Scaffold (2017) form a remarkable diptych of psychological implication and physical detail, portraying construction-worker protagonists whose visages remain unseen. Cutaway focuses on its hero’s dirt-caked hands as he grasps various power tools, applies tape to a cut on his palm, and responds to texts from a pregnant friend. Radwanski could have layered an explanatory score over these images, but he sticks to the mundane sounds: the whine of the machinery, the hum of an ultrasound appointment. Scaffold might not deal with a plight as life-altering as this, but in depicting the house renovation work of a pair of recent immigrants to Canada, it reaches similarly insightful heights through its curation of tactile gestures. As the men attend to their duties, peeling away walls and climbing ladders, their chitchat emanates from off-screen. They delicately negotiate their dynamic with the widowed homeowner who hired them, fielding her complaints about dust and weighing whether it’s OK to use her bathroom.

With their deemphasis on the human face, these shorts mark outliers in Radwanski’s career. Most of his movies take place in unwavering close-up, clinging to the faces of his characters. His earliest shorts apply this style to a generationally diverse array of personalities in extremis: a 19-year-old confronting the ramifications of a drunken encounter with the police (2007’s Assault); a woman experiencing the onset of Alzheimer’s disease (2008’s Princess Margaret Blvd.); a real estate agent undergoing midlife malaise (2009’s Out in That Deep Blue Sea); and two schoolchildren facing the disciplinary aftermath of their roughhousing (2010’s Green Crayons). As in Cutaway and Scaffold, Radwanski plunges us into physical activity: furious sessions on the elliptical in Out in That Deep Blue Sea, disoriented wanderings around the neighborhood in Princess Margaret Blvd. But he also fixates on bureaucratic settings—the offices of lawyers, doctors, and principals—as his characters butt up against regulatory strictures.

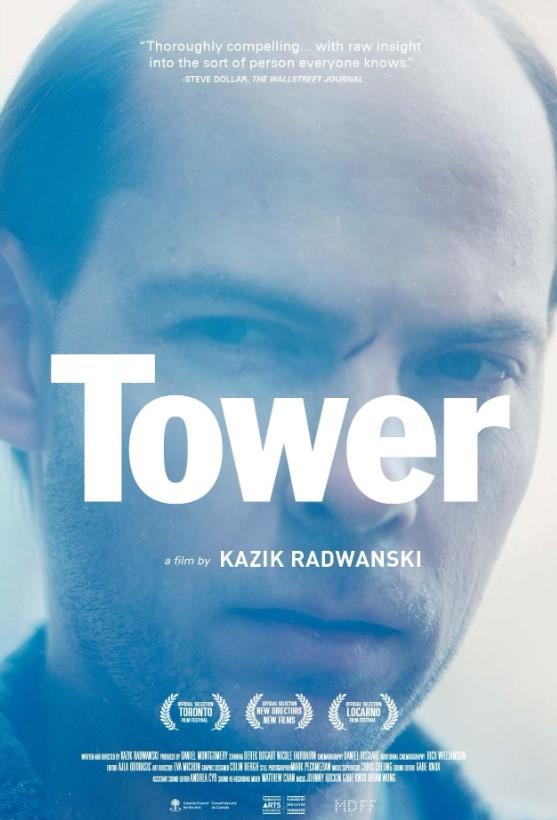

Radwanski—who was born in Toronto and has shot all his work in and around the city—transitioned to feature-length filmmaking with back-to-back abrasive male character studies. In Tower (2012), mid-thirties loner Derek (Derek Bogart) subsists on construction gigs for his uncle and lodges in his parents’ basement, where he toils away at an animation project. One of Radwanski’s characteristically strained social encounters sees Derek screening his work-in-progress video for his parents’ business-minded friends, who awkwardly muse about its “merchandising possibilities.” In How Heavy This Hammer (2015), discontented family man Erwin (Erwin Van Cotthem) unglues himself from his domestic responsibilities, shacking up in an apartment above a bar and living out a clumsy period of newfound singledom.

For his most recent features, Radwanski has applied his rough-hewn approach not to relatively unknown leads but to an onscreen duo of professionals: the actress Deragh Campbell (I Used to Be Darker) and the director Matt Johnson (BlackBerry). In Anne at 13,000 ft (2019), Campbell stars as a daycare worker whose fondness for mischief tests her relationships. Johnson’s character meets her at a wedding, where he helps her survive a nightlong champagne binge. In Matt and Mara (2024), the two play old college friends reacquainted amid the confusions of their thirties—Campbell a now-married creative writing professor, Johnson a vagabond author newly returned to Toronto. With its focus on artistic types conferring in academic settings, Matt and Mara puts forth a calmer aesthetic than Radwanski’s previous work. But even this movie of writers and thinkers carries peculiar jolts, like how Matt’s hand suddenly darts into frame to tap Mara on her back outside her lecture hall—his dramatic way of letting her know he’s back in town.

I recently spoke with Radwanski—who studied film at Ryerson University, now Toronto Metropolitan University—over Zoom. He frequently referred to his artistic process as a kind of “chase,” a fitting word for a director who keeps his camera in such constant motion. He also explained his distaste for backstory, discussed his work as a professor, and reflected on his characters’ emotional extremes and the fine line between “unhealthy” and “cathartic” behavior.

I love the feeling of being very close to someone but not totally understanding them and still being mysterious. I find something very cinematic about that [...] I like preserving that sort of in-between as much as I can. And ellipses and gaps are one of the tools I use.

Danny King: Going back to your first short film, your style has been remarkably consistent: emphasizing close-ups, using shallow focus, and staying close to the characters. Why do you think that was so fully formed from the beginning?

Kazik Radwanski: I’m not sure, and I’m not sure if it was fully formed at the beginning. There was always a spark or a fascination that I would try to ground my work in. If I felt curious or was fascinated by something, then perhaps other people might be. I definitely remember feeling that way with the early shorts, Assault and Princess Margaret Blvd. Even work I made before that, when I was a film student, it was that feeling of capturing something slightly beyond myself, or discovering something through a performance or through a moment. So, I've tried to find different ways of finding a similar feeling.

Most recently, with Matt and Mara, it's these two personalities, these two actors I really love. I just love putting them in a scene together and seeing how they interpret it. But it's a similar impulse all the way back to the beginning. My earlier stuff was a bit more doc-focused. There's more of a fascination with real people or real personas—finding an outsider or a nonprofessional actor and learning about them on screen, and then slowly tailoring the film to it. This is still a similar process, but it's now learning about how my friends create and how they react to situations, and how they creatively want to navigate them. It is a similar impulse, but it's growing in different directions.

Danny King: Another thing that struck me with the early films is the range of life experience on display. Was this something you processed at the time?

Kazik Radwanski: I remember it being intentional—that I wanted to challenge myself. When I made Assault, at least within film school, people were like, “That was great. Do that again.” And I wanted to do the same thing again. I wanted to maintain a similar approach but navigate a whole different sort of life experience. The breakthrough with Princess Margaret Blvd. was that I often felt depictions of Alzheimer's or dementia or old age were always sentimental, always from the viewpoint of the family and being sad about what they're forgetting. I felt like I could make a film where it's momentary, where it's the person, but it's in the present tense, and we're not creating meaning from backstory or through family members shaping it. There was some vitality there. That's an instinct I have—doing the opposite. Working with Deragh, I feel like we have so much in common, and in other ways we’re such opposites. Even just putting Matt and Deragh together, there's a provocation in these combinations. I think it was a similar impulse with Assault and Princess Margaret Blvd. [In] the later shorts, I was doing a similar thing, but with form, in avoiding faces—which I relied on for so long. In a crude way, I like to throw a wrench in my process. It's just a personality or a creative trait that I like those challenges. I like working with animals, because there's an immediacy in that. I like working with children. It's also maybe why I like teaching at a university. I like being with amateurs. I like things that create a visceral atmosphere, and then learning how to record it, interact with it, and shape it or be inspired by it.

Even Anne at 13,000 ft, right? Like, “Let's jump out of a plane.” I prefer something tactile like that to have as a foundation or a pivot. Back to your first question about early work, you said it was “fully formed,” but for me, I was thinking, as a young person, “What can I do? What can I bring to the table?” Because I like watching other filmmakers' personal work. I like when things are a little raw, a little reckless. There was some awareness early that, if I can do this and other people can’t, if I can offer this take on it, it'll be different than what's been made—because of this energy, or this approach, or this intimacy, or this lack of access to a location, or this access to a performance. That's always been, in place of a budget, what I look for—something that can be priceless or hard to accomplish in other ways. I think Matt has those instincts too, and Deragh does as well. We each embrace those elements.

Danny King: Matt and Mara feels a touch calmer than your other work. Could you talk about settling in with the conversation scenes and how they were perhaps cut a bit differently?

Kazik Radwanski: Conversation is the key. That was something we were after in this film—the feeling of conversation, being pulled into a conversation, and forgetting how you found yourself in that conversation. Or, more broadly, how Mara found herself in this situation with Matt. That feeling of being pulled into a conversation, and then suddenly slammed out of it. The coffee shop scene, in particular, with the music interrupting the conversation. Even the whole crisis or conflict in this film, it's sort of small conflicts, small things. Suddenly, someone realizes what they're doing, or has a moment of awareness. Quite intentionally with Nikolay [Michaylov], the DP, we experimented with gimbals. At times, we would use sticks. At the end of Anne, there are moments of that. There are a few scenes where it becomes stationary. In general, there's normally much more of an objectifying of the conversation, or being so focused on someone. And that happens in small ways in this too. I still have the same editor who's cut all of my work, Ajla [Odobasic]. Even when we're shooting these conversational scenes, we're not shooting a two-camera setup where they’re always single takes and there's that dance of, “Do we want to be on the person listening or the person speaking?” We really like to sort of play and explore that.

Obviously, this is a less frenetic and claustrophobic film than Anne. With [the] gimbals, it was difficult because the ideal choice would have been Steadicam, but it's impossible to have a Steadicam operator for the number of shooting days. In total, this was approximately a 65-day shoot. You could do 20 days in a row with Steadicam. Even that would be difficult. So we investigated a lot of different, more accessible gimbals, and finding a shooting system where we could shoot on Yonge Street or shoot on location, have a small footprint, but still be able to stabilize the camera and have that flow or immersion in a conversation. The starting point was the walking scenes with Matt and Deragh. Those were a lot of the early scenes we shot, and it was partially us figuring out how to stabilize it, how to even show, with continuity, where they are walking. We had a few different strategies of doing a loop or having a set route, but ultimately we ended up just walking in one direction, and we would keep going in a straight line. That sort of worked. It would be an hour or two and we would do five or six 10- to 20-minute takes, reset, and then do another take. In terms of the process, it was sort of flowing into conversation, getting a feel for that. Then it evolved into the sit-down scenes, and more of almost a shot-reverse-shot cutting style. Which is something that has happened in my previous films, but in this film, in particular, there's a lot of conversations.

Someone observed something too [about] the car scene. I have quite a few car scenes in my previous films. In Tower, there's that car ride with Danny, [Derek’s] co-worker, and in Anne, there's that scene with her co-worker, and also with Matt. In this film, too, there are conversations that are flowing and they're moving around, but suddenly they're confined or trapped in this car, which I found interesting. In contrast to how some of the other scenes had this looseness to them, this was locked in. Deragh, I liked [her] a lot in that scene. I love her body language and the way she sort of turns. It worked out really well dramatically, or in terms of their blocking, to suddenly have them locked in this uncomfortable moment, and it being forced to be resolved, or not resolved, but hashed out, or fleshed out. There was nowhere to [go], no release. They had to lock in with each other. There's this dance they're doing throughout the film, and then suddenly they're in that moment.

Danny King: Your characters have peculiar passions or hobbies: Derek’s animation, Erwin’s fascination with a video game, Anne’s skydiving. But they can have trouble balancing those pursuits with their day-to-day responsibilities. What is it about these characters that keeps them from finding the ideal balance?

Kazik Radwanski: I gravitate toward figures and how they don't fit into society or community. [In] Anne, there's the daycare, and that's kind of a microcosm for society. Green Crayons, similar territory. Assault, too, that was always the earliest idea: He’s an adult, but this guy cannot talk to a lawyer, he doesn’t have life skills, he’s not an adult in so many ways, but he’s capable of being tried like an adult. He’s at an age where his actions have consequences. So that thread's always been there. But it really started with Tower. A lot of the protagonists are artist characters. With Tower, I love the idea of someone who was an artist, a creative, but hadn't found their voice or didn't know [it], and there being a tragedy in that. I feel like a lot of people know people like that. They'll have a nephew or a cousin who has perfect pitch or is incredible at drawing, but they'll just draw, like, sports cars. I love that idea of this tragic artist-like character. That is also there in Hammer with the video game and the rugby. I don't know if artist is the best word. But I like that as a territory to explore a person or how they're trying to find something or interact with the world. It's there in Matt and Mara, with them being writers. What emerged throughout the shooting as well was her husband, Samir [played by Mounir Al Shami], and music, and conversations about music. How do we navigate our work, and how do we relate it to each other? I like it as a counterpoint to relationships.

Danny King: Your characters often have living situations that are uncomfortable or uncertain. Is that another element of the question of fitting in?

Kazik Radwanski: I think so. Tower, I wrote that when I was 24, and Derek is 34 in the film. In my head, it was my fear of myself in 10 years. You have this dream of being an artist, and where does it go? And this fear of being behind or not being able to connect or explain yourself. Or, again, that scene with Danny, where he's almost lying about having a relationship or relating to other people. I think the living situation is part of that.

The progression with Hammer was a character like Derek, but a father, or the head of a family. And imagining someone like that being depressed or having a crisis while people are relying [on] them. To have a powerful person be in that crisis. Anne, it was a similar arc to Tower: “Can I be in relationships?” That whole mini-arc with Matt, and then with her mother. This idea that there was a trauma in the past, too. Can she move past that? I can see parallels between Matt and Mara and Hammer. The crisis that Mara finds herself in is similar to Hammer, but more subtle. A lot of it is [her] meeting with Matt and it's that pocket of time in the afternoon where you have free time, or it's her hanging out with someone. I remember having that feeling when I've been in a bad patch of a relationship. You'll be hanging out with someone or having brunch with people, or often it'll be at a film festival or something, and it's like, “I don't do this with my partner anymore. I miss this.” Which, back to the question of the home, it was just there being a place outside the home for connections. And then that contrasting back with home. But also, Matt is sort of a homeless character in the film. Revealing where he lives, it was a bit of a thing. It's almost Matt crashing into life and not actually knowing what his living experience is, or where he's living, or how long he’s going to be here for. So that became interesting—not showing someone's living situation, keeping that sort of vague.

It was a huge thing for Deragh, in that car scene where they're fighting, Matt says, “I love you,” and then Mara says, “You're not allowed to say that.” I always find that heartbreaking. Mara is saying that because Matt isn't sacrificing anything. He doesn't have a family, he's not in a relationship, so he's not allowed to say that to her. That was at least, I think, Deragh's conceptualization of Mara. Matt doesn't have that life experience to have integrity to say things like that. Mara in some ways is viewing him as not a fully formed person. I think there's different ways you can interpret it, but that to me seemed like a real kernel of contrasting where they were in different parts of their lives. It's easy to view Matt's character as this antagonist, this manipulative guy coming in, but I think there's a bit of a tragedy to him as well.

Danny King: That disconnect reminds me of the breakup scene in Tower.

Kazik Radwanski: Yeah, him rejecting someone. It's so long ago now that I made that film, but I think Hammer and Tower are both similar, somewhat depressed characters. But it was that feeling that they didn't want other people to know they were depressed, that they could rationalize it on their own. It was this fear of intimacy or this fear of rejection. I was in a strange place when I made that film. It’s one of those films I'm glad I made because there were so many unusual feelings that feel so far away now. It definitely was a very young, angsty film. The strategy back then was to have these personal ideas and then feel [and] filter them through a persona like Derek or Erwin. I think back then, I knew these were sort of ridiculous feelings, but I loved finding a common ground or a way to navigate it through Derek or through Erwin.

Tower, 2012 film poster

Danny King: There’s another pattern of characters getting injured in your films: Derek’s forehead scar; Erwin’s rugby cut; in Cutaway, the bleeding hand. What appeals to you about having a wound as a symbol or a practical element?

Kazik Radwanski: In Tower and Cutaway, it was a really important symbol. I think there's that element too in Anne, where we don’t see what it is, we don't know what her diagnosis is, we don't know what medication she's on or what treatment she's receiving, or the full context of it. With the cut on the hand, and the cut on the face, it's superficial. I think it's a similar statement. In Cutaway, I was intrigued by having that as a timeline—to show this cut happening, it heals, but that’s in contrast to the crisis the character is going through that is a more evasive problem.

I was chasing a strange feeling with that film. I have a lot of experience working with my hands. My uncle, my father, I know people that worked their whole lives with their hands. There's a dignity and something powerful about that, but it's also quite easily a tragedy as well. I’m using the word tragedy a lot. But with Cutaway, on one level there was something empowering—that he's working through his feelings—but at the same time I saw a limitation there, or a trap. Is this healthy, or is this incredibly unhealthy? Is this cathartic, or is this someone having a meltdown or destroying themselves? With Tower, I think it's even more evasive. But if I'm being honest, it's something that literally happened to me. I was at a film festival in Poland, and I was very young. I was there with my third short, Out in That Deep Blue Sea. It was the first time I was in Eastern Europe. There was a lot of vodka. One night, I woke up and was blackout drunk, and I had a cut on my face, and no one knew how I got it. It was such a strange feeling to have this thing stamped on my face for the rest of the festival. It's the first thing someone asks: “How did you get that cut?” And then to figure out different ways to explain or not explain. Do I tell them I don't know how I got it? Or do I try to come up with what would be the best story? I felt like that mirrored Derek's existence quite well, of him trying to explain himself or be presentable. It captured this funny crisis he was in.

Also with Tower, I don't know if it ever landed for people, but the title itself was meant to be an enigma. Back then, I would describe the CN Tower as this monolith, and it was meant to be more of a motif in the film. I think you only see it a couple times. But when you live in Toronto, there's this big ugly building in the middle of the city that you forget is there, and then sometimes it's there, and somehow for me it's slightly in parallel with the cut on his face. It's there, [and] you have an explanation for it, or you don’t. There's this big thing, and what does it mean, does it mean anything? Or is it just a meaningless thing that puts a pin on it for you? When it premiered at Locarno, Mark Peranson emailed me being like, “What does Tower mean?” I gave him that whole spiel, and he wrote back, “How disappointing.” I think it's that the CN Tower is a lame reference, but it was intentionally lame. It's meant to be this self-effacing [thing], like Toronto. And that's a big part of what I, being a filmmaker from Toronto—what can we offer? What's interesting about Toronto as being a type of city or place? What is a crisis in Toronto? At the time, I felt it was someone like Derek that felt like a uniquely Toronto type of person.

Danny King: It's interesting to think of you as a regional filmmaker because, given the close-up style of your work, it's not like you come away from your films and necessarily know what Toronto looks like or know what a certain character's neighborhood looks like. It's more of a psychological or emotional portrait.

Kazik Radwanski: At times it creeps in. There are moments where it does seem on the nose, it being Toronto. Like the raccoon in Tower, or Tim Hortons in Hammer. There are moments where it does become almost kitschy. But I'm more interested in a certain type of alienation in the city. I remember thinking that when I was younger. Even just contrasting Toronto to Paris or London or New York. Or crime and conflict in other places of the world. Obviously, there's crime and unfortunate things that happen in Toronto, but to me, as someone who grew up here, it's a safe city in a lot of ways. But people are still alienated, people are still depressed, people still have crisis. That's what I was always trying to find.

With Matt and Mara, I love that tension of how people choose to engage with the film. Did something happen, or did nothing happen? Spoiler of the ending, but that little piece of paper [a dry cleaning receipt with the words “Matt and Mara” on it], I love that as a symbol, because it's something you could throw away, it's something scribbled on a piece of paper, or it’s something you can keep in a book and it can mean something. This is a brief couple of weeks or months between Matt and Mara. I feel like Matt moves on, but I think Matt fully went for it and poured his heart out. Mara didn't, but Mara might be haunted by it. Maybe it's a survival technique, but I almost like that feeling that someone could watch my film and feel nothing, and somebody else could watch it and feel very moved by it. There's something exciting about confronting that. Having something that could work for someone and not work for other people is something I've learned to appreciate about my work.

Danny King: I also liked the detail of Matt’s book and his biography on the back cover, and then you also show Mara's online university bio.

Kazik Radwanski: A big part of that was Emma [Healey], who plays Mara's friend. She's a published author, a working writer. We were designing Matt’s book, trying to build his persona. At the same time, Deragh and Emma are such good friends that Emma was helping Deragh write lectures. They were looking at different syllabi and different lectures, slowly figuring out a character, what she would teach, what the assignments would be. And that was going so well. I started asking her questions about Matt: “What do you think about Rat King as a title?” She’s like, “That's perfect, that is the type of symbol or kind of male thing from about 10 or 15 years ago.” And, like, what kind of advance would he have? Just asking her more of those questions. We were like, “OK, we should put her in the movie.”

That was a principle for the whole film, back to that word “conversational.” We wanted people that have had many conversations about books or authors or music. That scene at the dinner table, Mounir is a musician—it's his music at the end of the film—but also at that table are two or three other local musicians. Those are real anecdotes they're saying about touring that we wanted. With Matt too, it was the starting point—his persona as a filmmaker. I've been doing interviews with Matt. It sounds like his class visit [in the film]. He does speak that way, he has that motor. Matt also teaches from time to time. So just his persona as a filmmaker, as someone who's a little controversial. As Emma would say, “shake people out of their complacency,” and that's something Matt loves doing too. It was his idea to use his own name. Deragh, however, it's an important distinction that she's not playing Deragh, she's playing Mara.

Danny King: I wanted to ask about your work teaching filmmaking. What have you noticed about your students’ viewing and creative habits, and has that informed your work?

Kazik Radwanski: I love teaching. I prefer working with amateurs than with professionals. You can see it with some of my casting decisions. I like people that are genuine, and I find students have so much integrity. Everything is life-and-death. They're so excited, they're so nervous about filmmaking, but they're also so passionate. I constantly find that inspiring and like to surround myself with people like that. I find it very difficult working in film or commercials or TV as a hired gun or having other hired guns on set. It's not for me. I'm around enough students and professionals to know filmmaking is a career where you have to find your own path and it's such a complicated process that you have to figure out what works for you. But what works for me is being inspired by other people and working with other creatives that are also trying to discover or chase something. That's always present at film school.

With Matt and Mara, thematically, the scenes in the office are really important, when [Mara’s] having office hours. We had young actors audition or come in with their own work. I wanted that vitality, that vulnerability. I think that's part of [Matt and Mara’s] connection. They knew each other when they were in that moment, their initial friendship. It was that raw and they had that much integrity. Now this is 10 years later, and they've drifted apart. Or maybe Mara has forgotten that feeling and is just remembering it.

Deragh Campbell in Matt and Mara, 2024. Courtesy of Cinema Guild

Danny King: All your features have been between one hour and one hour and 20 minutes. Is there something about paring back that appeals to you?

Kazik Radwanski: With Matt and Mara, there was at one point a long cut of the film. There was a three-hour cut. I do like short films. I like short features. Someone said that to me, [about] the way time occurs in my films, like a compression of time. Certainly, something I do like quite a bit is ellipses. I collaborate with Ajla in a number of ways, but I definitely do like removing things: “Do we need this?” I'm always quite harsh with the footage and really experiment with taking things out and just cutting straight to a thing, removing setup. In Anne, there was a lot more context in the screenplay. There was more information about her diagnosis, her medical history, her relationship with her mother, and it became more interesting to remove it.

In Matt and Mara, there was at times more information about Matt, and we found it interesting to remove that and to know less about him. To know less about his father, less about the book he's writing. It became more exciting, more engaging, to remove those things. One thing that has emerged in my process is there’s the initial fascination with a subject or a moment, but it's also playing with it, intentionally disorienting the audience. Sometimes it'll be the camerawork and not establishing other people in the scene, and other times it'll be removing information. I want to foreground the character in a way that I find them interesting. I don't want to give an easy explanation early on. I don't want the audience to prejudge them and feel like, “We understand what's going on here.” I love the feeling of being very close to someone, but not totally understanding them and still being mysterious. I find something very cinematic about that. There's a feeling of wanting to remove information or frame it in a way so people are still forced to interpret the person, or engage with them in a simple way, rather than, “Oh, they're doing this because of that, or because of this.” I like preserving that sort of in-between as much as I can. And ellipses and gaps are one of the tools I use.