Courtesy of Larissa Pham. Photo by Sylvie Rosokoff.

When you’ve been living on, or with, the internet for over a decade, it can be difficult to recall your first encounter with a writer that you’ve become closely acquainted with over the years. When that first encounter isn’t a book—but an essay, conversation, or even simply a diffuse involvement in a certain school of online writing—it absorbs into the larger web of your own personal internet ecosystem. I thought my first brush with Larissa Pham was when I read her essay Crush in The Believer, but upon revisiting it, I found it was only published in 2021, and it feels as though I’ve been reading Pham for much longer. “I know and have worked with a lot of Canadians,” Pham told me when I voiced this sensation to her. She cited proximity through the years to essayist and critic Haley Mlotek, for example, and having written for the short-lived but stunning Adult Magazine, run by Sarah Nicole Prickett. “We probably have some overlaps,” Pham said. These moments of overlap are really a sign of communion: of mutual interest or even fixation on certain works of art and the writers who write about them. And for Pham, one thread of interest is precisely this sensation of communion over art.

When Pham’s last book, Pop Song, a collection of essays on art and intimacy, came out in 2021, she did an interview with Montréal literary podcast ‘Weird Era’ in which she said “intimacy is a matter of surfaces.” Most people, I think, would bring up imagery of depth when thinking about intimacy. But in Pop Song Pham was invested in interrogating surfaces for all that they imply (that which lies beneath them) but also what they themselves, being so intentional in their cautious representation, can offer. “When I say I have a crush on you,” Pham writes in the essay Crush, “what I’m saying is that I’m in love with the distance between us.” In addition to her own books, Pham’s work has been included in several anthologies about desire.

Through all of Pham’s work, there is an attention to visual art. Artworks, and in many cases paintings, are used as sites to explore ideas, to prompt reflection, to coax out story. And now, in 2026, Pham is releasing her first novel, Discipline. Discipline is about a painter, Christine, who has given up her practice after a painful, power-imbalanced entanglement with her mentor and professor—who is, for the most part, referred to as ‘the old painter.’ Unable to continue with her art, she takes up writing, which leads her to publish a revenge-fantasy novel.

The classical structure of the künstelrroman, the artist’s novel, or apprenticeship novel, follows a protagonist as they develop towards their eventual artistic success. Discipline warps this archetypical trajectory by tracing what happens when an artist’s progression is thwarted by an abuse of power that prevents development, when the artist is pushed into a different form of expression, and what happens when that secondary form is still soured by what happened, even when the work itself is a success.

In her experimental book Prairie, Dresses, Art, Other, Danielle Dutton has an essay on ekphrastic writing, ‘The Picture Held Us Captive.’ She considers fiction as a place in which we might ‘attend to the world.’ “The job of art is to make the world strange,” she writes, “rather than simply recognizing it out of habit.” Pham, I believe, after reading her work and speaking with her, agrees with this notion. Why else might a painting of a glacier make you think so much about divorce? Why else might the sudden simultaneous bloom of daylilies feel so related to a bright spot of a political movement? Why else might Discipline end the way that it does?

What do painting and narrative have in common? One answer is they both simplify things [...] in making art we simplify, but in simplifying we can say something true.

There are several essays in Pop Song that use a structure of cataloguing—numbered fragments or paragraphs—as the essay’s format. The essays oscillate between themes of intimacy, desire, engaging with cultural objects, and personal narrative, and you catalogue these revelations and anecdotes and moments. When I was reading Discipline, I thought about how it could be read as an expansion of that style. Each chapter of the first half of the book centres around visiting a new place, revisiting one of Christine’s relationships, and contending with one artist in particular. What does the cataloguing form allow you as a writer?

I call them the list essays, but I think cataloguing is a better word. I wrote ‘Crush,’ ‘Dark Vessel,’ and ‘Camera Roll,’ which are all in that structure, at a residency in New Mexico, and I was reading—and this is a very millennial cliché—A Lover’s Discourse and Bluets. I was interested in how the numbering gave the essay an internal propulsion. There wasn’t a lot of connective tissue, it was really just bone. That was liberatory in terms of drafting those essays in particular. I was thinking of Pop Song as a catalogue of modern intimacy, and the push and pull that technology has on how we connect with each other. Although I think that book became more about the technology of writing and language and how those things come up as barriers between people.

I’m still doing those same things in the first half of Discipline, and I think part of that is a product of wanting to write fiction and wanting to structure a book around these encounters with paintings and with people. Discipline actually began as a project—which it is not anymore—for a book called ‘Ten American Paintings.’ I wanted it to be very gnomic, almost hermit-like, little meditations on American painting. I was really interested in it not being read—I wanted to write something that was very private. But then I thought: what if I took this structure of encounters with paintings into fiction, and had a woman moving around the country looking at things? It is a very familiar form for me—art and viewership, and relationships—but when I was writing it, in fiction, it became almost all connective tissue, in a way.

Fantasian was fiction, and you’ve written short fiction as well, but from Pop Song to Discipline, how was that jump of forms?

I love writing fiction, I would say it’s my first love. Realistically, I couldn’t picture a way to get a career off the ground as a fiction writer, so I started with writing book reviews and essays, because those are things that you can actually publish and make money doing. And I do love the essay form. But what unites those three projects is first person. First person in Discipline allowed me space for some of those essayistic meditations that I really enjoy writing. Christine thinks a lot, and it was really enjoyable to think in her voice. But the exciting part is that in fiction, so many other things enter the formal mix: character, plot, pacing. There’s a flexibility to first person that I really enjoy, and a way you can move that first person closer or further. There are moments in the text that are very Outline-esque, where Christine recedes so far back to let another character tell their story. And [Rachel] Cusk didn’t invent that, the porous narrator is a nineteenth century thing, you know? Like, there’s a guy who’s like ‘I keep the ledgers in this town, and I’m going to tell you about all the affairs!’ Or like in The Secret History.

In Pop Song you have these really precise moments between the narrator and unnamed ‘characters.’ In Discipline, because it’s fiction, was this a place where you felt like you could expand beyond the surface intimacies you were interested in tracing in Pop Song?

Pop Song is about the narrator—which in that case is me—trying to exert a power over her life through storytelling. In Discipline it’s much more about Christine listening, her porousness. Something I had written on a sticky note on my computer was: ‘how should we live?’; I was thinking of Sheila Heti’s How Should A Person Be? Christine is interested in how other people live, so I wanted to allow her these long glimpses into other people’s lives. I realized that’s a way to get to talk about ideas, and I really like when novels have conversations about ideas.

You’re doing a lot of ekphrastic writing in this book, but through the lens of a character. It’s funny you bring up Cusk because I returned to Second Place as I was reading Discipline, feeling this Cusk-connection. I wanted to see if there was anything in the books that felt like they were speaking to each other. There was this one passage where the narrator of Second Place is talking about the idea of things happening to you, and you can’t remember a time before they were happening to you—in this case, the narrator’s experience of being criticized—so they feel inseparable from your sense of self. And then the passage comes to: “But my point is that there’s something that paintings and other created objects can do to give you some relief. They give you a location, a place to be, when the rest of the time the space has been taken up because the criticism got there first.”

I was interested in this idea of a painting functioning as a location. I have my own ideas about what Christine’s perspective on the function of paintings for her might be, but I was curious what you thought of as the function of paintings for you.

I really admire Cusk, and clearly this book is in dialogue with her work, but I also don’t agree with her on a lot of things. On what art is, on what relationships are… I find Cusk to be kind of cynical, and maybe a little bit more down on the human condition than I am—that’s probably a sweeping generalization, but I disagree with her sometimes as much as I respect and admire her. I find Second Place to be a book about the tyranny of artmaking. Speaking as myself and my own relationship with painting, there are two reasons why I love it. As a craft, it’s so enjoyable. It feels really good to paint. And the formal vocabulary: shape, colour, stroke, texture, surface—I really enjoy looking at all of that, and looking at how other people have done it. This is probably something I gave Christine; she’s interested in the formal architecture of painting, always talking about brushstrokes and the way things are composed.

My second love of painting, which I didn’t really give to Christine, it’s just for me, is: it’s just such a different medium from writing. You look at a painting and you look everywhere. When you pick up a book, it’s a prescribed form. There are lots of people who have tried to interfere with the form of the novel or narrative, I’m personally not that interested in that, I’m not a language poet. But with painting, it’s completely different, and maybe that’s why I’ve never tried to disrupt writing, because painting is right there, all at once. It gives you more the more you look at it. And maybe there’s a secret third thing for me, which is that painting is so rich. There’s just so much in a visual language that can be conveyed, and when you call upon it in writing, it brings so much power. Invoking the spirit of Edward Hopper, invoking the spirit of Vija Celmins. Brings this rush of associations in a way that I don’t think I was completely aware of when I first started.

If I may quote your own book back to you…

I’m ready!

There’s this spectacular line that relates I think to Christine’s perspective on painting, but I think can relate to writing too. She says: “Life was all around us, all the time. Sometimes, I thought, it felt like there was too much of life to handle—too much detail, all cramped into reality, from which we could rarely escape. There was no filter, no strategic compression of narrative through which we could fast-forward—just the onslaught of each moment and its accompanying sensation.” I wonder if this relates to Christine’s impulse around painting as a way of existing outside of time, away from the clutter of life.

What do painting and narrative have in common? One answer is they both simplify things. When Christine is thinking about how overwhelming life is, sometimes there is too much life, and there’s too many memories. And Christine’s approach has been to rewrite her own memory, to become this sexy bitch and kill her abuser. That’s the way she deals with it. And maybe it gestures towards the larger project of artmaking, which is that in making art we simplify, but in simplifying we can say something true.

Now that we’re talking about the novel within the novel, I was thinking about the term ‘mise-en-abîme,’ which translates to ‘placing into the abyss,’ and is an art history term for a painting that has a small version of itself within the painting. I think I first learned about it in a class that was talking about Velazquez’s painting ‘Las Meninas’ where there’s a small mirror within the painting, reflecting the subjects of the painting, so that there’s a doubling in the image. And so ‘mise-en-abîme’ is this idea where there’s a mirror or a small version of the image you’re looking at placed within the work you’re looking at. There’s the sensation of infinite reflecting. In Discipline, there’s the novel within the novel, and we don’t read it but we learn about it. How were you contending with the novel within the novel as you were writing?

I love a metanarrative, I love thinking about what is it that we’re doing when we write, and what is it that we’re doing when we try to make something. From the beginning, I knew that Christine had written something. It seemed important that I not include sizable sections of the book for logistical reasons. I don’t really enjoy reading long sections of a book within a book, and it has to be handled really well. It’s not always effective either.

And you maybe don’t get that quality of the mise-en-abîme in the same way if the novel within the novel is taking up the same amount of room as the actual novel you’re reading. It has to be buried, or placed. There’s something really fascinating about knowing that Christine’s novel exists, but not actually reading it.

It’s better when some things are a mystery, too. The very first draft of Discipline didn’t include the fragments between chapters that are in the first half of the book, and those were inspired by my Canadian editor, who suggested including excerpts of Christine’s book. I was thinking about Hot Milk by Deborah Levy, where it has these ambiguous bolded sections, where you don’t know the POV. So those interludes are the only text we have of Christine’s actual writing, and I wanted those fragments to feel different tonally. I think Christine is a pulpier writer than I am.

To me the most important function of Christine’s own novel is how she talks about it and how she comes to her own understanding over the course of the book that she was constructing something in order to live, she was doing her own bending and twisting and versioning of the truth. And that’s what the old painter says about it—that he could recognize it and didn’t recognize it.

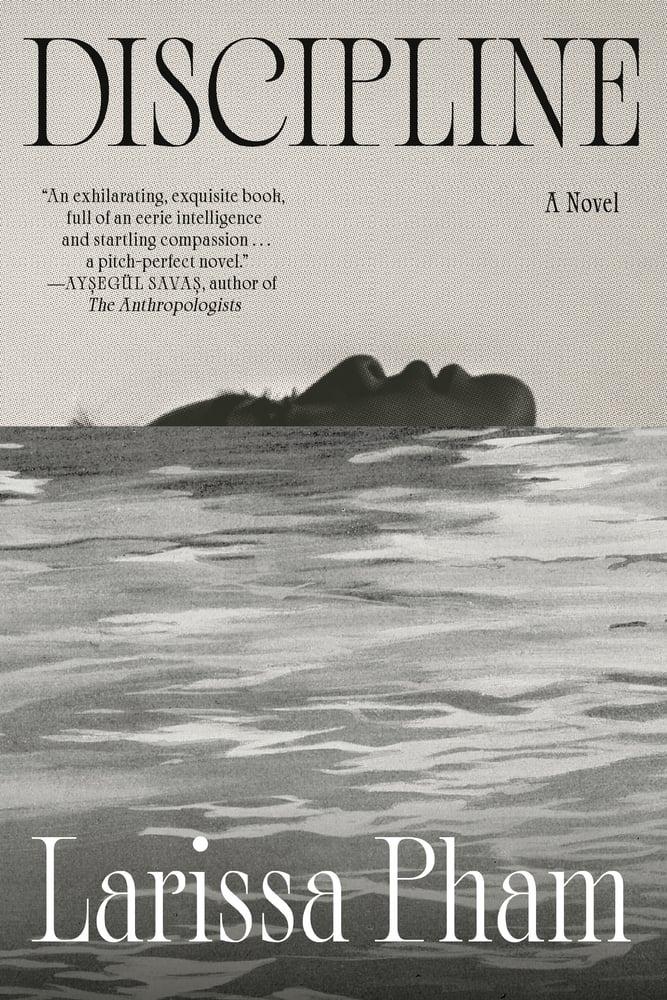

Book Cover for Discipline. Sourced via.

In my preparatory notes, I have a question under the heading: Being forsaken through the patheticness of authority figures—a bit of an absurd line that I wrote after reading the poignant, hilarious, and slightly devastating moment in ‘Dark Vessel’: “a professor accidentally left a whole page of porn tabs open in his browser while trying to navigate to a YouTube clip from The Birds. It wasn’t the moment itself that bothered me; it was that I was paying so much to be lectured at by someone who didn’t understand the concept of a private browsing session.” This struck me because it aligns with a significant theme you've taken much further in Discipline with Christine and the old painter: the way that trauma and pain can also be twinned with a strange mix of other feelings when the person holding power both hurts you, but also reveals themselves to be pathetic in a variety of ways.

Without giving too much about the book away, I'd love to hear how you approached such a thorny theme, and how you were able to find yourself writing towards a place that breaks new ground on this subject (as I believe Discipline does).

Once I decided that they would meet, I became interested in finding a way to equalize Christine and the old painter somehow, to bring them to each other’s level. Their age gap, which feels so significant when Christine is in her twenties as a graduate student, seems to collapse a decade later—because they’re both truly adults, they’ve become peers. Even the moniker of the “old painter,” while being appropriately sinister, is Christine’s attempt to knock him down a bit, to take away some of his power. I’m really interested in this connection you drew because, though it wasn’t my intention, there clearly is a thread there—this aura of the pathetic that lives inside men who would like to have power over us, or who do. And maybe it’s that weakness, or frailty, or bathos within a certain kind of man that leads him to want to claim power over someone younger and less resourced. Or conversely, maybe it’s the recognition that power gained through exploitation isn’t real power which creates that aura of the pathetic.

With the old painter’s character, I was interested in finding moments where his humanity is revealed to Christine—she’s spent so much time thinking of him as a villain, but in reality he’s just a guy. There’s something humbling, maybe even embarrassing, about realizing that this monster that you’ve created in your head isn’t really a monster, right? She’s plotted all this violence, and yet. And at the same time he has done her harm, he has changed the course of her life. I was really interested in the ambiguity and yes, thorniness of this situation. I know that Christine’s story isn't particularly new, but I did want to take it into new territory by having these characters actually speak to each other—I wanted to see what would happen if they could be honest with each other, and what it might take for them to get there. Without giving anything away, part of that meant giving these characters things to risk—both of them. Some of my favorite scenes are the ones in Maine, where Christine and the old painter are just hanging out, talking, almost verbally sparring. So much arises in that discomfort, but I think that messiness is what makes us human.

How do you approach ekphrastic writing?

It’s different whether I’m doing it in fiction or nonfiction, because that will change whether it’s me or the character working through it. I teach a graduate literature seminar on short experimental books, in which we read Borealis by Aisha Sabatini Sloan. I’m a big fan of Sloan, she’s an arts writer, and she does classic art reviews, but she also works visual art into her essays in a really compelling way. In Borealis, she writes about these Lorna Simpson paintings of glaciers. There’s a beautiful passage where she describes a painting, but also uses her point of view to exert something onto the painting. She’s reporting on this encounter between her and the painting that’s so charged and so personal. She’s like, ‘I think this painting is about divorce.’ And when I look at that painting, I don’t think that, but she had this encounter with it, and she has written it down for everyone to see what kind of encounter she had.

And so what I tell my students is that in arts writing, there’s a component that’s very art historical, where you’re thinking about material, you’re thinking about technique, the history of the sales and the gallery that represents them, the art historical aspects, but there’s also the point of view that you can provide. What do you see in something, what touches you? What does it awaken in you? And that is the place where I begin my more creative ekphrastic writing. That’s something that makes its way into the fiction, because what a character notices can contribute to their characterization or to the plot. There’s a lot of personality that can go into arts writing or ekphrastic writing.

It’s a double lens that you’re writing through, when you’re writing ekphrastic writing in fiction. And I want to talk about Christine’s relationship to fiction. There’s a part with her ex-partner, where they’re talking about how he can’t handle the gaps between the book she’s written, which has bent or moved the facts of reality so that the book (which is fiction) portrays what feels truest to her experience. He is having a hard time dealing with that gap, balancing the external facts versus her internal facts. There’s another passage where she’s talking about the idea of roleplay with a partner, saying, “What my ex and I had never learned was how the act of being someone else can set the true self free. When we pretended, we layered on levels of artifice. Instead of revealing something we couldn’t say any other way, we just covered everything up.”

When you’re writing fiction, do you have a method for yourself to work through when there may be a level of artifice, or when the construction is allowing you to speak about something that feels more true?

I cannot abide by an emotionally untrue moment in a book. When I read something and feel that the character wouldn’t do what they’re doing, then I don’t trust the writer anymore. I really want to trust the world of the book, and if the world of the book starts messing that up—and not in a productive or experimental or fun way—there’s a collapse somewhere, a hole. When I feel myself moving towards a place of artifice in my own work, the work gets flat and I get stuck. If I’ve written myself into a corner, it’s because I started doing something that’s not emotionally true or convincing. It doesn’t mean that it has to have actually happened to me, or even someone I know, but if I am writing and there’s a false note, I can get only two paragraphs past that, and then I hit a wall. Fiction is all about emotional truth for me, so when the work is flowing it’s because it’s coming from that place of emotional truth. So I can’t say exactly what the mechanism is, other than when it stops working.

You have a newsletter, ‘Yield Guide,’ which is about observations on nature, “devoted to slow looking,” as you call it. We haven’t talked that much about the second half of the book, and I don’t want to give away anything to readers, but there is an attention to the natural world that comes up in that section. When did you find yourself turning to writing that engages with nature?

I grew up in Oregon, which is a very pro-plant state, and in Portland, which is a very pro-plant city. I grew up with a familiarity with the natural world that I assumed everyone else had. I never considered myself outdoorsy until I moved to New York City. When I moved to the Hudson Valley in 2023, I started really thinking about nature writing. There was a moment where I realized all these plants do something. I’d also been spending more time in nature because I was in a grad program at Bennington. Katy Simpson Smith, a faculty member there, wrote a really great book called The Weeds, which is all about plants, and each entry in the book is inspired by a specific species of plant found in the Roman Colosseum. If you’re interested in nature writing and how a novel can be structured in an unconventional way, I definitely recommend it. Ultimately, it all started with noticing—I tell my students that noticing and paying attention is the first step of being a writer. I wanted to translate this experience I was having with the natural world, wanting to learn things, notice things. Especially being up here too, you feel the weather and seasons a lot more than you do in a city. I live in a pretty small town. I remember in the summer, right around the time that Zohran Mamdani won the primary, all the daylilies were in bloom, they all popped open at the same time, and I was just like, oh my god: celebration.