Meshes of the Afternoon, directed by Maya Deren, 1943. © Tavia Ito, estate of Maya Deren, Re:Voir Video.

In August of 1945, the friendship between avant-garde filmmaker Maya Deren and writer Anaïs Nin turned into a nasty feud. Deren immortalized the clash in a poem dedicated to Nin:

For Anaïs Before the Glass

The mirror, like a cannibal, consumed,

carnivorous, blood-silvered, all the life fed it.

You too have known this merciless transfusion

along the arm by which we each have held it.

In the illusion was pursued the vision

through the reflection to the revelation.

The miracle has come to pass.

Your pale face, Anaïs, before the glass

at last is not returned to you reversed.

This is no longer mirrors, but an open wound

through which we face each other framed in blood.1

Their relationship had initially blossomed as neighbours in Greenwich Village and they eventually became collaborators on the basis of their shared interests in self-reflection and living their lives as artistic experiments. The rupture between the two occurred because of their opposing views on postwar aesthetics, namely how new technologies would impact the psychology of individuals, and artistic production in turn. While Nin preferred narcissism as an artistic strategy, obsessively writing diaries in hopes of discovering deeper truths about herself, Deren opted to experiment with techniques of self-recognition, believing that narcissism was a failure to consider oneself amidst external conditions. Deren’s poem alludes to the trappings of narcissism, wherein obsessively examining the self amounts to the endless repetition of woundings and misrecognition; a compulsive interest in plumbing the depths of oneself does not always create a fruitful foundation for relationships with others.

The motif of the mirror occurs again and again in Deren’s film and writing oeuvre, a mark of her concern with the psychodynamics of relating to others while forming distinct identities. A hooded figure with a mirrored face originates in her first experimental film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)—a figure which has recurred in art and visual culture over the near century since. Running through these examples are the shaky interpretations and projections of self and other: dissociation, fragmentation, and the potential for integration. The mirror mask stands in for a psychic space in which it is never quite clear whether the real or the fantasy is more disturbing, positing that the two dimensions sit side by side in discourses on identity formation. This proposition highlights the disagreement between Deren and Nin on the relationship between individuality and postwar shifts in technology and culture, and how artistic practice has responded to these changing structures. Namely, by orienting more and more towards video-centric industries like surveillance and television as outgrowths of wartime military research, slowly morphing into social media and an influencer-marketing industrial complex over time, ultimately a socio-cultural climate oversaturated with self-regard and anti-social tendencies has developed, which Deren would have abhorred.

The central epistemological shift post-WWI was towards identity; psychoanalysis and anthropology stepped in to answer questions around identity formation through appeals to otherness. Jacques Lacan wrote of ego development in the mid-1930s with his theory of “the mirror stage,” suggesting that the ego is founded by first observing oneself in the mirror as a child, thus seeing the self as an image. Prior to this, Lacan proposed, the body is perceived of in pieces; the imaginary unity produced in the mirror stage, then, is forever threatened by this memory of fragmentation, which deploys the ego like an armour against anyone and anything that represents an external danger. Lacan’s theory of the subject is not necessarily historical, though it describes a modern subject that is paranoid, guarded against otherness broadly (both within and without).2 While the discourses of the 1960s and ’70s derided the authoritarian character of institutions and proclaimed the death of the universal humanist subject with revolutionary intent, through texts such as Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth, the 1990s more firmly naturalized identity discourses in the form of multiplicity, bringing heterogeneity and previously ignored subjectivities to the fore in cultural and political settings. Western conceptions of individuality prevail through Modernism and Postmodernism, changing form periodically in relation to shifts in culture and technology, often plunging people deeper into paranoid self-regard that permeates the cultural as much as the social.

The mirror mask has reoccurred in culture to continue a long exploration of the interdependence between reality and fantasies of the self, a matrix we can never really grasp nor escape. The search for clarity never ends, like reflections upon reflections that go on forever.

The art of cinema, and performance by extension, is a technology of direct encounters with the self, the other, desire, fantasy, and reality, allowing us to think visually about how to reconstitute being in the world. By overcoming limits of time and space, cinema operates with fictions that use the coordinates of the mind as it attempts to put the self back together, as it were. Deren made Meshes of the Afternoon at age 26 after her father died of a heart attack. Previously working as a journalist—of which he disapproved—she used her inheritance money to buy a Bolex 16mm, changed her first name, and took up filmmaking. Deren’s relationship with her father was so foundational to her identity that she wrote to a friend following his death:

I was a growth from and upon his mind and soul so that I was always a part of him. That is why our relationship was almost pathological…. we always had to converse with a third person in the room whom we addressed, instead of each other. For we were really one person and you cannot speak to yourself… How can he be dead and I alive since we are one thing?

Starring only herself and her second husband, Alexander Hammid, Meshes of the Afternoon plays out Deren’s tumultuous internal struggle to differentiate herself from her deceased father. The film features four versions of Deren—personalities in conflict, one wields a knife that threatens to kill another—and the film culminates in Deren’s suicide, ostensibly from a piece of a broken mirror. Taken as a means of working out her self-proclaimed pathological relationship with her late father, the film suggests that she must “kill the father ‘organically’ inside her so that a core self can emerge.” Deren insisted that her work not be analyzed with a psychoanalytic lens, though it is near impossible to sidestep the self-reflexiveness of Meshes on the face of things, nor the biographical events that seem to undergird it. However, this kind of defensive refusal of psychoanalytic interpretation is often precisely what indicates the looming presence of a deep-seated psychological wound coming to the surface.

The hooded, mirror-faced figure steps in as an emblem of this wounding, a lifelong failure to constitute one’s self. Some critics and scholars suggest that it is a spectre for confronting one’s own death. This would seem apt in context, as Deren questions how she continued to live when her father had died if they shared one singular identity. The constant reflecting in the film suggests the self breaking apart into pieces, toward the pre-mirror stage, on the one hand attempting to become distinct from her father, and on the other, feeling literally fragmented as a result of his permanent absence. Deren’s ego disintegration in the film goes through quintessential processes in analysis from alienation and dissociation, toward the possibility of reintegration beyond death. The making of this film in the very recent wake of Lacan’s writing on the mirror stage makes for an obvious citation, but this mirror mask’s function has stood the test of time even while epistemologies of the self have transformed, and amidst an expanded (technological) object domain for observing oneself. Like Lacan’s paranoid, post-mirror stage subject, the mirror mask is not historically determined but rather continues to function as a stand-in for the complexities of modern identity configuration, despite the ways in which media have accelerated the infiltration of the psychic and social structures that facilitate alienation throughout the past century.

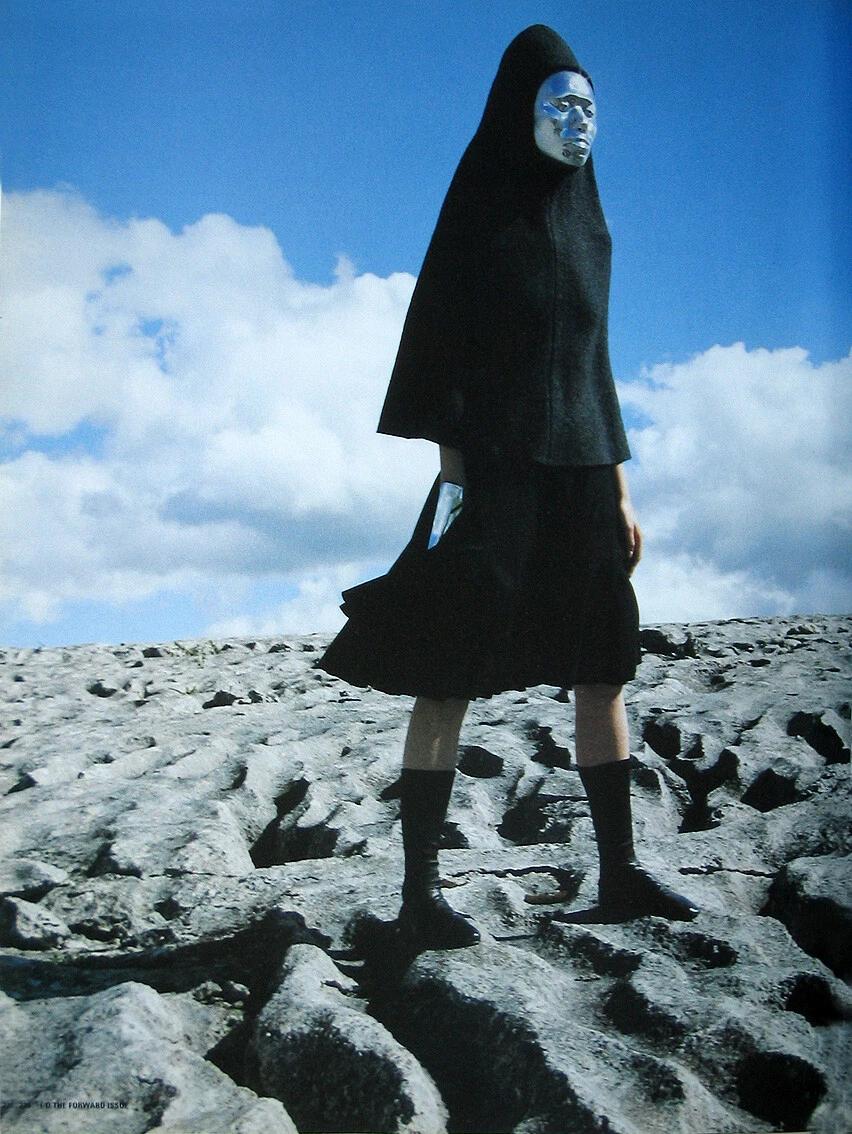

Carter Smith, “Koyaanisqatsi,” i-D Magazine 180, “The Forward Issue" (October 1998).

Signe Pierce, American Reflexxx, 2013. 14:02 min, https://www.youtube.com/

One of the earliest reoccurrences of this figure, cloaked in black with an oblong mirror for a face, is in Sun Ra’s proto-Afrofuturist film, Space is the Place (1974), directed by John Coney. Struggling against the limits Sun Ra saw in earth-bound humanity, particularly for Black people, the film posits a Black future, drawing directly from Deren for the hooded, mirror-faced entity that accompanies Sun Ra to the distant planet. That the figure is a silent companion speaks once again to the idea of multiple selves defamiliarized from others, but reflects them back just as well. An October 1998 editorial in i-D magazine, titled “Koyaanisqatsi” after Godfrey Reggio’s eponymous 1982 film, likewise had Canadian actor-turned-model Shalom Harlow donning a black, cone-headed hood covering from Hussein Chalayn’s fall/winter ‘98 “Panoramic” collection, with a mirror mask sculpted into a face. During the runway show for this collection, several models wore these masks while turning and walking to observe themselves in standing mirrors on the stage. The show notes included a quote from Wittgenstein as the collection’s inspiration: “Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must be silent.” Within the context of the mirror and the mirror mask, this framing suggests the failures of language to describe oneself or another, a faltering of recognition as it passes between us or passes us by.

The 1990s saw the mirror mask enter the lexicon of music videos with Milla Jovovich’s homage to Deren in the video for her song “Gentleman Who Fell” (1994). Later, the directors of Yeasayer’s “Ambling Alp” (2010) and Janelle Monáe’s “Tightrope” (2010) both also admitted to direct influences through the lineage of Deren vis-à-vis Sun Ra. Both videos traffic in the psychedelic and futuristic, in a newly post-2008 world in which the full range of economic consequences had not emerged entirely, and when even artists’ visions of the future reached back into the twilight of revolutionary fervour from the 1970s. These contemporary examples reveal how an anxiety about visibility—a desire to somehow disappear and be seen all at once—is acculturated in the burgeoning plurality of knowable identities of the 1990s, in the shadow of the triumph of capitalism and a politically unipolar world, and when the world began to play out largely on television.

Angelika Festa’s 1984 performance, You Are Obsessive, Eat Something, anticipates this conflicting anxiety-desire, also foregrounding its particularly gendered aspects. Festa stood for several hours at the side of a country road in a modest black dress and hood, hands and feet painted white, holding a bowl of fruit and wearing a mirror over her face. The only documentation of the performance exists in Peggy Phelan’s landmark 1993 book, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. Phelan casts the crux of this work as tracing the “passing of the woman’s body from visibility to invisibility, and back again.” The mirror functions as a tool of recursion, through which both artist and spectator endlessly pass their appearance and disappearance back and forth to each other. Following in the footsteps of Deren’s hooded mirror-mask figure, Festa visually suggests a parallel with the concept of Deren’s multiple versions of self as they reflect the other, inciting fear. In one moment, Festa is hyper-visible because she presents herself as a faceless other. In the next, her facelessness disguises her position as a human subject, instead reflecting onlookers back to themselves. The presence of the mirror throws the obligation of visibility onto the spectator who is reflected in its surface, turning quickly to disidentification when this reflection is recognized as being tied directly to another.

Phelan contrasts this with Yvonne Rainer’s film, The Man Who Envied Women (1985), in which the protagonist is a woman who is never actually shown in the film. The “drama” of Festa’s performance, Phelan writes, “hinges absolutely on the sense of seeing oneself and of being seen as Other,” which occurs for both parties simultaneously. In Rainer’s film, the woman cannot be seen, but in Festa’s work, the woman cannot see, and can only partially be seen. The mirror fragments the body by detaching it from the human identification tied to faciality; “Sight then is both imagistic and discursive.”3 The “complete” body withdraws to become a body in pieces once again. As a device meant for reflecting what is, the mirror as a replacement for the face results in further fragmentations and multiple disidentifications that affect the standard relations between people.

What actually occurs through this defamiliarization? A rather noteworthy and unintentional answer to this query comes through in AMERICAN REFLEXXX, a 2013 performance work by self-described “reality artist” Signe Pierce, in which she went to the boardwalk of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, wearing a curved mirror mask over her face and renouncing the black hooded cloak for a blue mini-dress with lime green high heels. The performance itself was very simple, in that Pierce spent an hour walking the streets of the tourist strip being filmed by her then-partner, filmmaker Alli Coates, but what unfolded was an unpredictable and irreplicable first-hand examination of “dehumanization, mob mentality, [and] violence,” especially in relation to gender presentation and sexual otherness. The two had originally intended nothing more than to make an aesthetically beautiful video work of Pierce’s “cyborg” character to show at Art Basel Miami, but the performance ultimately culminated in an assault that left Pierce bleeding on the sidewalk.

Almost immediately, a shirtless man approaches Pierce (who, to be clear, is a cis woman) and grabs her without her permission, sexually solicits her, and asks his friends to take his photo pretending to lick her masked face. Within a minute, Pierce is followed by a crowd that only continues to grow throughout the performance. One person can be seen multiple times throughout attempting to trip or slap Pierce; some hurl water from water bottles—eventually escalating to throwing full water bottles—but some of the most jarring harassment comes in the form of consistent transphobic comments and epithets. The climax of AMERICAN REFLEXXX occurs when an adult woman runs towards Pierce from behind and shoves her full force to the ground. Even while she lies motionless and bleeding, the crowd stands around filming her with their phones, insisting she take off the mask.

In the minds of her aggressors, Pierce’s lack of a distinctly human face justifies the violence they inflict on her. What the performance reveals is a very deeply inscribed semiotic system for reading gender presentation and sexual difference in public space and the violence that ensues when someone does not conform. Deliberate facelessness by way of a mirrored mask conceals what might be the one signifier of her “real” identity, causing horrifying confusion, leaving her humanity open to interpretation. Pierce expressed later that with the escalating harassment and assault, her response was to be even more provocative, and it was important to her not to give her audience the satisfaction of forcing her to unmask. By de facto mirroring her surroundings, including those who approach and assault her, Pierce demonstrates how these onlookers do not see her as a person, and instead only see themselves. Those who encountered Pierce’s character during the piece decided on instinct that she was in the wrong place (that is, by daring to be in public), and punished her for it in myriad ways including non-consensual touching and sexual advances; had she been in one of the many strip clubs dotting the boardwalk of Myrtle Beach, the fetishistic, erotic, and enticing readings of the spectacle would have taken on different meaning within the sanctioned boundaries of fantasy and transactional contact (not to suggest that this is always safer).

Following Pierce’s revelations on facelessness and gender performance, Spanish artist R. Marcos Mota performed The Ultimate Strategy in Drag at Centro Parrága, Murcia, as part of Disfonías curated by Jesús Alcaide in 2016. Wearing a mirror mask and layers of white lace and tulle, Mota proposes what they refer to as “ontological transvestism” (translated), considering the body as a process rather than an object. Facelessness here is a de-gendering, a suspension of fixed identity, used intentionally rather than what Pierce had uncovered accidentally. What persists regardless is the mirror as a tool of projection. The question of fantasy as it pertains to the gendered—or even non-gendered—body is nearly impossible to decouple.

In the performance works of Festa, Pierce, and Mota, as Phelan writes of Festa: “The more dramatic the appearance, the more disturbing the disappearance.” For all three, the mirror is at once a mask and a means of reflecting the spectator (and their actions) back to them, but this element of the horror of facelessness seems to also justify, or at least hint at, some level of dehumanization. Art does not occur within a perfect moral universe since it is predicated on the pathologies of the one we actually inhabit. There is an inherent desire in all of us to know where we belong, to be able to place ourselves among others, and them amongst us. Inherent to cinema and performance is a crucial and unique opportunity to explore fantasy and reality horizontally; as such, we are able to stage fictions about who and what we are in order to understand. This is the offering of Deren’s work now: A prediction of our increasing alienation from the legacy and impact of post-war technologies into what we know them to be now. The mirror is the preindustrial analog of the camera, the TV, the surveillance apparatus, the smartphone. It predates what Rosalind Krauss designated the fundamental narcissism of early video. The intransigent triumph of individualism coalesces under fears of oneself, fears of the other, fears of desire, as well as the double-edged fear and desire of being observed. The mirror mask has reoccurred in culture to continue a long exploration of the interdependence between reality and fantasies of the self, a matrix we can never really grasp nor escape. The search for clarity never ends, like reflections upon reflections that go on forever.