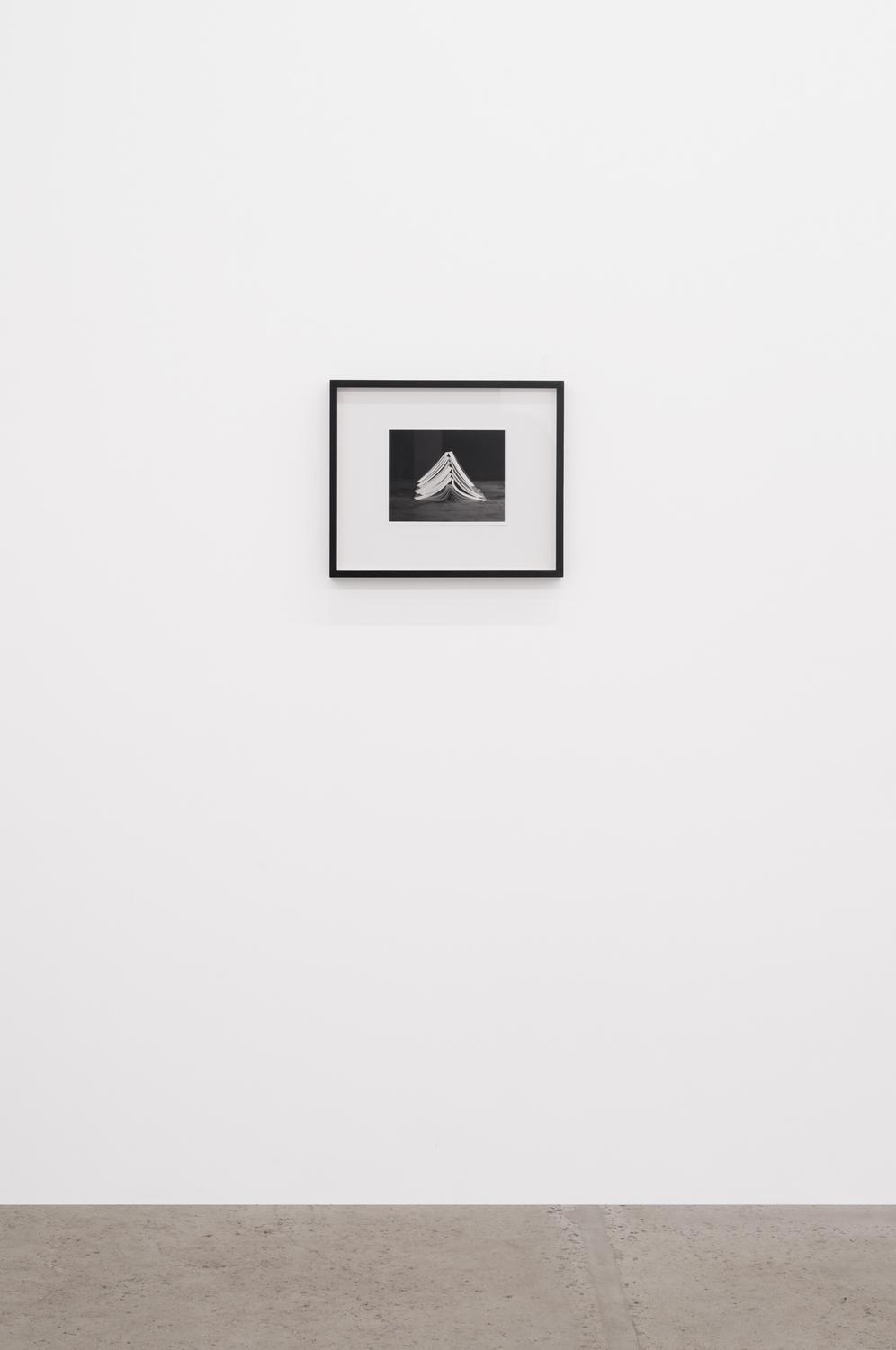

Livres 8"x10" silver gelatin print part of Maison de plage, 2024 at Galerie Eli Kerr.

I ran into Alexis Auréoline at an art opening a few months before conducting this interview. As we got to talking, he revealed that his favourite ice cream flavour was French Vanilla, with an emphasis on the distinction—it had to be French. I was amused by this choice, but later, after having had the pleasure of sitting down with Auréoline to discuss his work— which is similarly subtle and precise—I consider this preference to be essentially on brand.

Auréoline is a Francophone Métis artist working across photography, painting, and frottage. He is perhaps best known for his large-scale cyanotypes—a cameraless photographic technique that involves treating the canvases with light-sensitive chemicals and allowing the image to slowly develop as the surface is exposed to UV rays. Patterns emerge across Auréoline’s art practice. The figure of a chevron appears prolifically—and by way of repetition, the significance and ambiguity of this symbol unfold. They might index waves, road signs, or something else entirely. When I encounter Auréoline’s work I’m immediately reminded of the pared-down aesthetics of Minimalism and the attuned passion of Abstract Expressionism. Although Auréoline started his career as a photographer, a label with which he still identifies, his work reveals a conspicuously painterly quality. In our conversation, we discussed his eclectic influences and the hybrid nature of his art practice.

Since returning to Winnipeg after an extended stint in New York (via Halifax), Auréoline has been producing large-scale works on canvas in addition to his darkroom practice. Part of the bargain of moving back to the Prairies, the region which Auréoline is from, is that the city currently affords him the space required to indulge his appetite for scale. The interview was conducted in Aurêoline’s studio, where he also lives, a dreamily bright and spacious spot in Winnipeg’s Exchange District. The studio also held some of his most recent cyanotypes, featuring his signature chevrons and wood grain frottages. Several of these works were recently exhibited at the NADA Art Fair in NYC and at Art Toronto. This month, he opens the solo exhibit, 'Maison de Plage' in Montreal at Galerie Eli Kerr.

Auréoline’s practice is deeply rooted in a holistic relationship with materials and techniques from a pre-digital era. We sat down to discuss the conditions of making art, the dynamic between the centre and the periphery, and the importance of slowing down.

In the studio, there is a relationship with materials, tools, and natural light. It is important to be aware of the tools, their different sounds and senses, as well as the materials like canvas and wood. Allowing oneself to move these materials and tools around the studio is a significant part of my creative process. So, my approach to studio practice is to be very conscious of the surroundings, which is what I am trying to access in the studio.

Could you walk me through your trajectory as an artist?

I think it's good to start with my father being a librarian and spending a lot of my childhood in different libraries looking at art books. Then, in high school, I learned darkroom printing through a program at The Graffiti Gallery. I grew up outside of Winnipeg and a lot of my art education was through Border Crossings and Plug-In, reading a lot of articles and going to see a lot of shows.

After my first year at the University of Manitoba, I wanted to leave Winnipeg and got into NSCAD [in Halifax] where I focused on photography, painting, and sculpture. I applied because I wrote an essay on Joseph Beuys, whose performances and sculptures really moved me, and in my research, I discovered he had spent time at NSCAD. Although conceptualism wasn't as prominent there as before, it was still celebrated and taught. There was still some dialogue about what was going on in the Sixties and Seventies. Access to the NSCAD Library, reading about artists like On Kawara, Louise Lawler, Robert Smithson, and Agnes Martin, and being in an environment that encouraged this work was crucial. They had excellent visiting artists' lectures, one of my favourite ones was Abbas Akhavan.

In my last year at NSCAD, I did an exchange at the Cooper Union in New York and moved there. What can I say? It was a mix of everything. It was in Manhattan, so going to view shows at the Guggenheim and the Met and then coming back to the critiques and hashing those out was pretty exceptional. I did this semester at Cooper Union during their last free year, and so there were some important politics and questions about institutions that I experienced alongside the other students and the faculty. I was accepted into a Master's program at Hunter College in Manhattan where I did a few semesters before landing a job in art handling for a company that sponsored my visa. For years I moved artwork between Chelsea, the Hamptons, Lower East Side, and made sure that they would be shipped to Los Angeles and Paris. And that was my life in New York. A lot of it was going to see shows in Manhattan in the Lower East Side in Chinatown and Chelsea—from that, I learned a lot. I did a residency in Antwerp for a summer. COVID happened, and I moved back to Winnipeg and started making more work in isolation, informed by the culture and landscape of the prairies.

When it comes to legible influences, I see a lot of affinities between your work and Abstract Expressionism and also the Minimalist painters. You've already mentioned a few names, but could you talk about some of your artistic influences?

I think that the main influences that come across in these photos/paintings are Ad Reinhardt, Michel Parmentier, Roni Horn, and Agnes Martin. I appreciate the way Agnes Martin thought of herself more as an Abstract Expressionist rather than as a Minimalist because Abstract Expressionists allowed themselves to paint emotions and talk about these different feelings, whereas Minimalism was more concerned with these very cold calculated systems and methods of painting. I very much admire Agnes Martin’s systemic painting while she wrote and openly managed emotions. She's very much about space and solitude, and there are emotions, but her work was quite systems-based, so she was talking about all of these things.

Am I correct that she’s also from the Prairies?

She was born in the prairies and raised in Vancouver. It’s interesting because she doesn't refer to her paintings as landscapes but rather as a hopscotch grid. She moved to New York and had a successful career in Manhattan. However, she had some issues with renting a studio, I think it was demolished. She was part of this Coenties Slip crew who rented lofts with no kitchen or shower in Lower Manhattan. At some point, she decided to move to New Mexico.

Is the space of exhibition something you're conscious of when making the work? Do you think about the lifespan of your artwork outside of your studio when you are making it?

The space of the exhibition is always an elusive thought. I do really like to go see and experience exhibitions, some artists would rather stay in their studios (which I envy honestly) but I’ve realized I’m one of those artists who maintains connection through the experience of museums and galleries.

Architecturally, yes, I think of the space of the exhibition in terms of windows, walls, and lighting. Culturally, there are always some thoughts about a site-specific narrative somewhere.

Most recently, it's really been about lighting: a major component in how the works are going to be received. But sometimes those things are out of my control. I do know that in the studio I can control the lighting that I am viewing them under, and for me to sit with them and view them under that lighting, I think that's enough. That's all I can do.

Your studio, which we are in right now, is also your living space, and I get the sense that it occurs in that order. You live in your studio, rather than work in your apartment. Could you talk a little bit about just what your process and your routines look like around artmaking?

Yeah, definitely. It certainly has the appearance and layout of a studio that happens to have a mattress, kitchen, and bathroom. Moving back to Winnipeg, having a studio during the pandemic, and learning to be isolated and alone, was very productive for my studio practice. This wasn't as much of a thing in New York. As an artist who works with materials, finding time to be alone is always the goal. The cyanotype works that will be shown in Montreal at Galerie Eli Kerr were created over the summer outside of the studio, in my mom’s garden which she inherited from Elzear Lagimodière, one of Louis Riel’s council members. So those works are made on that specific site.

The cyanotypes are made outside, while the rubbings are made using the plywood surface from the studio table. The still-life prints of books are photographed here in the studio. Another important function of the studio that I value and think about a lot is the display (a term I prefer to staging). The studio involves a lot of decision-making regarding the display of paintings, such as which wall and height to choose. In this studio, I’ve been able to place large works on a wall and really live with them throughout the seasons. The artwork is then digitally photographed for documentation purposes, to see how it looks captured in an image.

These ones [gestures towards cyanotypes; Pénombre] are actually unphotographable. It will be very challenging to translate them through a photograph because it takes a while for your eye to adjust to the nuance of the different tones in the space. They could be retouched or composed in Photoshop, but I don't want an overly retouched look.

Pénombre 44" x 1" x 56" inches cyanotype on canvas

Beach House 45" x 1 5/8" x 94" inches cyanotype on canvas

Some of the artists whose practices I see reflected in your work, including Martin, have a strong spiritual bent. I'm curious, do you feel that your work also has a spiritual component?

It does, and I think there's a pretty good amount of literature about Eastern philosophy influencing a lot of Abstract Expressionists and Minimalists. It's not something that I think about in the studio, but I do think of the museum as a church.

Some very basic principles about mindfulness are helpful to think about when working with these paintings. And, it's kind of a clichê: less is more, but there's something about being mindful of the space and appreciating or working through the different senses, either that sound or light or emotion.

Can you expand on this idea of a sensorial response?

When it comes to viewing artwork, there are different ways to approach it. I mean, being in the studio (where I live) is a part of it. However, I try to separate the studio from viewing artwork. In the studio, there is a relationship with materials, tools, and natural light. It is important to be aware of the tools, their different sounds and senses, as well as the materials like canvas and wood. Allowing oneself to move these materials and tools around the studio is a significant part of my creative process. So, my approach to studio practice is to be very conscious of the surroundings, which is what I am trying to access in the studio.

On the other hand, when it comes to viewing artwork, the conditions play a role. I believe this is particularly evident when visiting an art show in New York. Climbing a few flights of stairs and entering a white cube gallery creates a contrast with the loud, aggressive, and claustrophobic city. This was something I became increasingly aware of in New York. The contrast between the city and the gallery is one of the important and special aspects of viewing an art show—it provides a significant break from the rest of the city.

Could you elaborate on your relationship with the materials that you work with?

For lack of a better word, I consider them to be analogue. I did some filmmaking and design in school, and I worked with screens and digital images for a while. While visiting studios around New York, I realized that many of them heavily relied on materials such as canvas, linen, and wood. Some art schools and programs have moved away from this approach, focusing more on design and media. Seeing this firsthand in different studios around New York and seeing the amount of material that is being worked through was a significant learning experience for me. The materials also serve a functional purpose in the space for instance, wood supports help hang the canvas. A very special moment in terms of moving back to Winnipeg is having access to different sites for dealing with materials, going to meet with different suppliers, and engaging in a community of people who have all this background about local material—that was really exciting as an artist to see what I could do with materials; cutting, stapling, ripping and burning.

In addition to these allusions to the natural world, which I find evident in your work, I also notice hints of a relationship between the cyanotypes and architectural blueprints, as well as a strong design aspect in the geometry of your work. I wanted to ask if the built environment is something you consciously draw inspiration from, alongside nature.

Cyanotype is a printing method with a strong history of being used to make blueprints. Although it's not my primary focus, I find it interesting that the material has also been used to reproduce architectural drawings. Instead of leaning towards the popular approach of copying leaves or flora, I have been working with chevrons. Chevrons are symbols that carry multiple meanings. Initially, I was considering water and waves as a symbol. More recently, I have been thinking about chevrons as a representation of roofs or different houses, as well as directional lines on highways. So, in response to your question about the built environment, I believe chevrons, which have sometimes been associated with roofs or drawings of homes, are significant. Additionally, there are the charcoal works that include prints of the dock bumpers found in the Exchange District.

Can you explain that process more?

Yeah, it's a technique called frottage, which involves rubbing canvas and charcoal on textured surfaces to create prints. I take charcoal and rub it on different dock bumpers around the exchange. These dock bumpers I copy and print from are old ones, wooden beams installed on the outer walls of historical buildings to prevent trucks or carts from bumping into buildings. I place the canvas over these wooden beams to capture the specific texture. I find this process to be a very engaging way to connect with the built environment, such as the local architecture and historical features of 20th-century buildings. These installed wooden beams were used to protect buildings or create barriers between the building and vehicles used for shipping goods. I haven’t shown or exhibited any of these yet.

Charcoal Painting #1 80" x 43" charcoal on canvas

I want to revisit the Chevron because it is a prolific motif that reappears in your work.

I think it comes from an interest in minimalism, systems painting, and even French conceptual painting. Picking a symbol and repeating it almost obsessively, and examining what that does for both the artist in the studio and the viewer. It’s a process of using that constraint to allow you to find some meaning that you value and that you can further explore.

You brought up the emotional vector of paintings, the colour blue has rich baggage in visual culture (I'm thinking Derek Jarman and Yves Klein). I'm wondering what is your relationship to the hue, its beauty, and moodiness.

Night Sky by Agnes Martin is a wonderful blue painting. The title says it all. This shade of blue reminds me of the area where the sky meets the sea, the blue sky, the sunset, twilight, and dusk. There are also significant cultural associations with water. Lately, I have been trying to explore my connection with water in my artwork, experimenting with various printing techniques. These pieces are intended to complement the waves or resonate with the analogue photos of water.

At this moment right now cyanotype is a very accessible form of printing, it's low toxicity and quite affordable. So I’m happy to work with it, and it's blue! What else can I say, I love the times of day dusk and dawn where the light is very blue because there’s visual uncertainty.

Another artist I mentioned who works with blue is On Kawara, there’s his room at the Dia Beacon I visited numerous times and a few of the paintings shift to subtle blues. I would look at a pair on the wall and find so much joy in the subtleties of blues. Ironically, Kawara has adamantly maintained that his choice of colour bears no symbolic weight.

In addition to the cyanotypes you also maintain a more classic photography practice. I was wondering if you could speak to that aspect of your work.

In New York, I was looking at a lot of darkroom prints, such as those by Moyra Davey and Zoe Leonard, which influenced my own work. These artists are skilled at producing captivating black-and-white prints, often with precise framing. The subjects varied but I always felt quite comfortable that there was something approachable about an eight-by-ten or eleven-by-fourteen darkroom print that was presented on a wall. Zoe Leonard and Moyra Davey are part of the reason why I am printing in the dark room. They're both very political, eloquent, and giving in terms of their beliefs, and how they use photography to narrate personal and political subjects.

Lately, I’ve been photographing with a medium format camera and printing still lifes of books in my studio. The images show books stacked on a table, highlighting how pages hold and archive information that informs our understanding of the world. While I'm happy to frame and hang these pictures, I’m particularly interested in presenting them near window light for its phenomenological effect. The challenge is that this light causes fading, posing an archival issue for collectors. To address this, I offer the entire edition with the frame: behind the print shown (1/2) is a second impression (2/2) stored in an envelope at the back. When the first print fades, it can be replaced with the second. This makes the piece a time-based work, complete with instructions handed over fully to the collector.

Maison de plage, 2024,installation view at Galerie Eli Kerr. Documentation by William Sabourin.

Livres 8"x10" silver gelatin print part of Maison de plage, 2024 at Galerie Eli Kerr.

Maison de plage, 2024, at Galerie Eli Kerr. Documentation by William Sabourin.

Maison de plage, 2024, at Galerie Eli Kerr. Documentation by William Sabourin.

You mentioned moving back to Manitoba during the pandemic. As a Métis artist, I'm curious to know if this move has had any impact on your work, considering Manitoba is the homeland of the Métis nation.

Moving back to Winnipeg, as a Métis person, involves navigating some trauma and grappling with family questions that can affect one's art practice. In my practice, there’s been a relationship between land and culture and I’ve been able to access spiritual connections during my time here in the Métis Nation.

Last year I was awarded a Canada Council Grant and was able to work with filmmaker Rhayne Vermette, visual artist Katherine Boyer, and curator Tarah Hogue. Throughout these consultations, we were able to discuss family stories, pretendians, and Métis art and design. Another important aspect is simply reconnecting with family like my mom, Ginette Lagimodière, and my cousin Vania Gagnon. These two women have raised me and hold wisdom, stories, and knowledge about these lands. As an artist being open about my ties to my Métis ancestry I’ll always be afraid of people expressing doubt about my claims but that’s for others to deal with.

Two poignant insights have emerged from our conversation. First, the enriching experiences of being in New York, where you have access to lectures, guest speakers, and galleries. Second, the value you place on having time and space for solitude. What are your thoughts on these two elements?

I'm constantly thinking about being immersed and then isolation. I'm still wrapping my head around it and trying to figure out if there's some form of balance there. I didn't produce much work in New York, for many reasons, but I have come to the conclusion that the main reason is that I was eager to attend a lot of lectures and shows to see what was talked about, and what was made. And I still had a full-time day job. I made attending lectures a priority, going to see exhibitions in Manhattan and I did learn a lot. I believe it was a very valuable time. Moving to Winnipeg in 2020 was somewhat accidental, but I had already considered it. I was questioning where I wanted to live and looking at artists like Agnes Martin and Donald Judd. Many artists eventually leave New York for the countryside or a small town and have a very spatial art practice. So, I was imagining that could be the next step or something I would do. When I arrived in Winnipeg, I wanted to look and experience the space, create larger-sized works, and experiment with different materials. In regards to your question about the value I place on having time and space for solitude, it is really about getting to know yourself and your surroundings.

I'm interested in hearing more about your relationship with these various mediums. Specifically, I'm curious about the frottages and cyanotypes, which seem quite distinct. What inspires these aesthetic shifts for you?

Yeah, I think there are certain questions I approach methods of printing with, questioning what it is, and how I can print this form. I could paint this with acrylic, but instead, I'm printing it with cyanotype. And that continues the conversation between photography and painting. You're not sure if it's a painting or if it's a photograph, so I love that uncertainty of what you're looking at. You’re also presented with a very old material of photography, and printing, and that's just me. I want to figure out these materials, and handle the canvas, stretch it, and expose it to UV light outdoors. It is a way of working that deals with the history of photography in the form of painting but has these conditions of producing them with UV light. They're quite risky. Both styles adhere to a method of printing that looks like painting because of their presentation on canvas and frame. And they are quite elemental.

While they are quite distinct in terms of materials, process, and image, they're really about pushing the boundaries of these elemental printing techniques, using a material like cyanotype or charcoal on a canvas. Both are printing methods that involve nature; the cyanotype relies on the sun and the charcoal involves burning and fire to produce a mark on canvas.

You mentioned the term "analogue" and there's a sense of something almost anachronistic in your connection to materials and your art. The cyanotypes, in particular, require a significant amount of time. With that in mind, could you discuss what attracts you to this pace?

It's a great question, and I hope that’s something that resonates with the viewer. The rawness of presenting technically crafted images, which are photographs created using the slowest method possible, is kind of funny and a complete contrast to how we usually consume images. Instead of urging people to slow down (but I mean, yeah, people should slow down) it's really just for me. My entire education, my entire life was dedicated to dealing with images and figuring out photography, so for me to choose the slowest printing process or the most archaic way of presenting a photograph is selfish. It requires a significant amount of time. Therefore, I have to be very mindful of how I handle these materials and of the time it takes.

It comes back to Agnes Martin and her relationship with emotions and tranquility, or the feelings that offer refuge, stillness, or repose. I create these works for myself, to have moments like that, and in a gallery, I hope the audience can experience the same.

I wanted to ask you about your future, what's on the horizon for your work and what you have planned.

I honestly have no idea. I can't be certain about what my future holds. I'm working a lot with Galerie Eli Kerr this year, and that partnership has been wonderful. In terms of what’s next for my studio practice, I would like to be happy making smaller works on canvas. I'm not there yet.