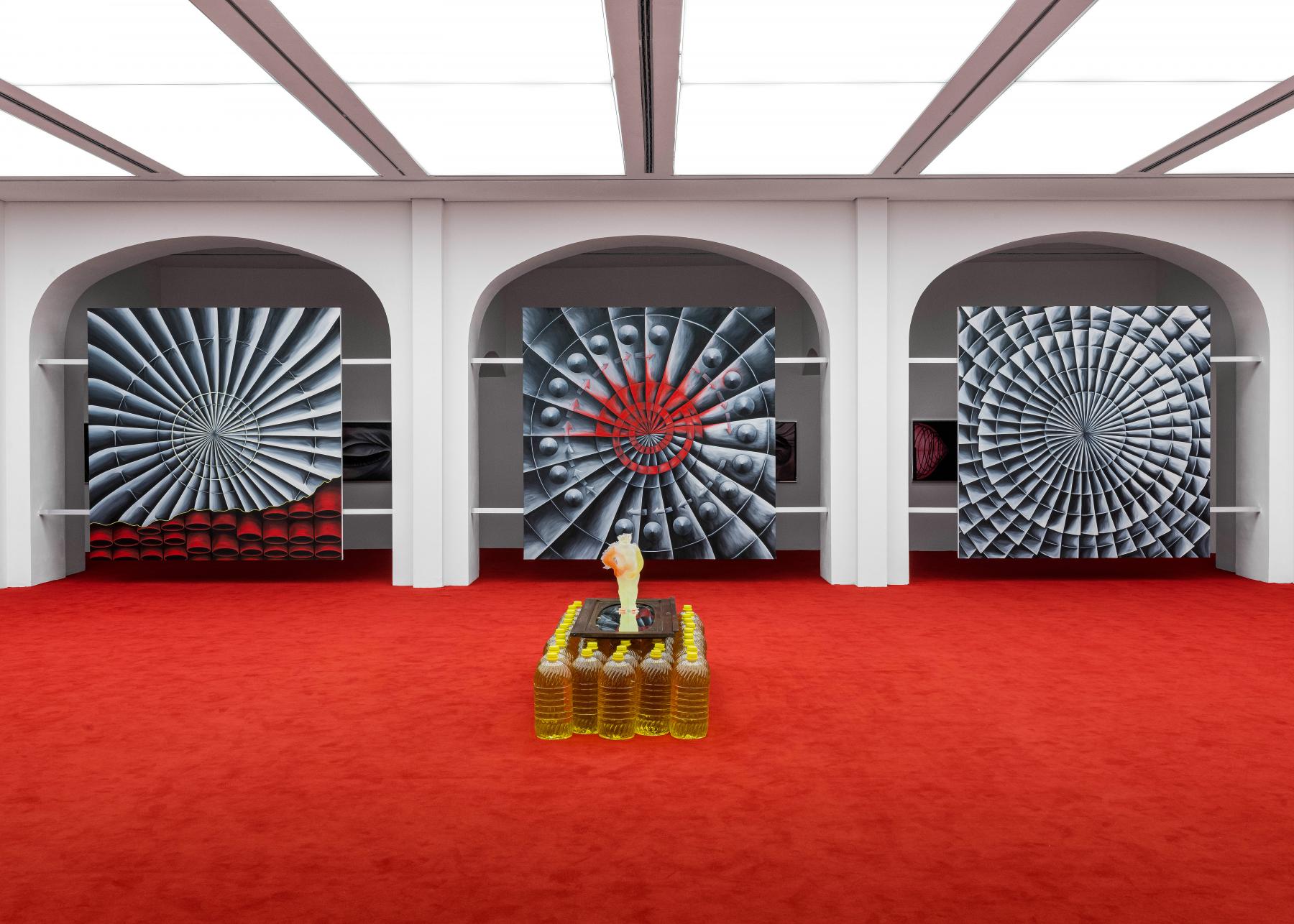

Rebecca Ackroyd, exhibition Tage und Nächte, 2025, Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Rebecca Ackroyd’s sculptural and pictorial worlds feel at once familiar and estranged. Dreamlike yet grounded in physicality, her practice spans drawing, sculpture, installation, and photography—often weaving together cast body parts, found objects, and domestic remnants into unsettling tableaux. Her figures, neither wholly present nor absent, evoke a surreal sense of interiority, vulnerability, and transformation. In her work, the body becomes both a site and a memory device—glitching, fragmented, and imbued with narratives that resist resolution.

Born in 1987 in Cheltenham, UK, and now based between London and Berlin, Ackroyd studied at the Byam Shaw School of Art and completed her postgraduate diploma at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Over the past decade, she has steadily built a compelling body of work that attracts international attention. Her recent solo exhibitions include Mirror Stage, presented during the 2024 Venice Biennale and organized by Kestner Gesellschaft, Hanover; Period Drama at the Kestner Gesellschaft (2023–2024); and Shutter Speed at the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Lyon (2023–2024), as well as solo presentations at Peres Projects, Berlin. She has also participated in significant group exhibitions across Europe and the Middle East, including the 15th Lyon Biennale (Singed Lids), Dark Light at the Aïshti Foundation in Beirut, and Antéfutur at the CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux.

In this conversation, Ackroyd reflects on how her practice has evolved over the years — not through grand statements, but through a continuous process of making, remaking, and revisiting. She speaks about working with cast resin, beeswax, and repurposed furniture as a way to embed history and transformation into material. Her ongoing exhibition Tage und Nächte at Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich (on view until November 2, 2025) unfolds from a deep engagement with the archive of Emma Jung, conjuring a psychological space where myth, dream, memory, and narrative construction intersect in subtle but powerful ways.

Ackroyd’s work can be seen in conversation with the surrealist lineage—particularly its contemporary reimaginings—drawing echoes from artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Medardo Rosso, or even early Rachel Whiteread, while carving her own distinctive terrain. At its core, her practice explores what it means to live with a body, to remember through objects, and to construct emotional architecture from everyday debris. This interview offers a glimpse into her evolving process: part subconscious drift, part sculptural precision, and always deeply human—anchored in material, but open to metamorphosis. Ackroyd’s ability to merge the personal with the mythic, the tactile with the symbolic, marks her as one of the most compelling voices of her generation.

I’m interested in the relationship between creating and the unconscious—in order to make work, there’s a process of switching off or deactivating a part of the brain. It’s a bit like losing control, much like dreaming [...] I want to surprise myself.

Rebecca, I first encountered your work in London nearly a decade ago. I remember being struck by how sensitively the works responded to the architecture of the exhibition space. How would you say your practice has evolved over the past ten years?

I feel like it never stops evolving. Every show is like another step where I think I’m closer to an idea, but then I always feel like there’s more to be done, more to learn. I often revisit old works or shows and think about them like different chapters in my life—they conjure different memories of where I was and what was happening at that particular point. It’s like creating a physical timeline.

To what extent do you consider the viewer when developing new work?

I try to block out the idea of people seeing it at all, to be honest—although that’s not always possible. I do consider how someone might enter a space or how I want the space to feel, but ultimately, I can’t control someone else’s interpretation, so I have to focus on what I want from the work.

Would you say you naturally gravitate more towards sculpture? How do you decide which medium feels right for a particular idea?

I usually work across different media, switching simultaneously between drawing, sculpture, film, and, more recently, photography. I think it depends on what I’m thinking about at the time.

Sculpture, for instance, has a more direct relationship, in its physicality, to the body and space. I see the process of casting in relation to photography—a “snapshot” of a particular moment. By contrast, using found objects roots the work in the familiar territory of the domestic or the ubiquity of consumerism. I recently repurposed furniture in an exhibition, using old clocks and wardrobes. Emptied of their belongings, they became like barren bodies imbued with a secret past.

Drawings, on the other hand, have an immediacy that feels like a much more direct line between mind and page. They can be private and transportable. No one process is more compelling to me than another, but I like the different perspectives they can bring to the table as a collective of voices.

You once said that “sculpture should be an active process, more akin to collage.” Could you expand on what you meant by that?

I was referring to a particular show I made—Period Drama at Kestner Gesellschaft in Hanover—where I wanted the sculptural installation to consist of component parts that were assembled in the space. I suppose I wanted to shift the way I thought of an object as finite.

The sculptures consisted of pieces of old furniture and tree trunks, and I bolted the cast resin pieces onto the found furniture as a way of layering the past and the present. The casts were repeated over and over, like stop-motion or slow-motion video stills dragged out across the space. I wanted the show to have a sort of chaos that connects to many ideas, actions, or places at once. Like a mind full of memories, it was incomplete and fragmented—like a party of micro dramas unfolding across a space.

Much of your work actually seems to emerge from a dreamlike space. Is that something you intentionally seek out, or does it happen more intuitively?

I think possibly a bit of both. As soon as I could speak, my mum told me I used to recount my dreams to her every morning. I carry memories that must have been dreams, but they blur with the reality of, say, a family holiday. It’s this fictionalization I’m interested in.

I’m interested in the relationship between creating and the unconscious—in order to make work, there’s a process of switching off or deactivating a part of the brain. It’s a bit like losing control, much like dreaming—allowing the mind to wander and seeing where it takes you. I want to surprise myself.

The human body appears frequently in your work; sometimes clearly gendered, other times more ambiguous. What role does the body play in your practice, and how do you think about the gaze?

I see the figures, or rather fragments of figures, as frozen moments in time—a phone call, a drink, a woman crying—they’re echoed, recast one next to the other, glitching. Each one is cast from the same mold, but they’re never identical. They’re crude and raw, like an imprint rather than an exact reproduction. The garden figures of children are often more dramatic, imitating Venus or the Manneken Pis, like bad actors disrupting the space.

Rebecca Ackroyd, exhibition Period Drama, 2023–2024, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hanover. Photo: Volker Crone

Rebecca Ackroyd, exhibition Period Drama, 2023–2024, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hanover. Photo: Volker Crone

Rebecca Ackroyd, The World as I feel it (Series), 2025, beeswax, stainless steel, Variable dimensions. Exhibition Tage und Nächte, 2025, Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Let’s talk about your ongoing exhibition Tage und Nächte [Days and Nights] at Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. What are you exploring there?

The exhibition is of my work and the drawings and diagrams of Emma Jung (wife of Carl Gustav Jung), which have never before been exhibited. The title is from one of her notebooks. I usually work in a way where a lot of the thinking comes through the making process, and so ideas evolve through a process of trial and error. There’s an element of not knowing where the work is leading that is important for me, so I end up in unexpected places. With this particular show, the works were also informed by the research into Emma Jung, which became more of a mindset than a literal response to her work—rather, I wanted it to flow through me.

I was particularly drawn to your beeswax sculptures. What led you to this material? And more broadly, what guides your material choices?

The material choices come from what something might represent or relate to. For instance, the translucent resin is supposed to be ethereal, or the disused furniture has its own inherent history. The material can imbue another layer of meaning into the work.

The beeswax pieces started as a small test. I was making works at home and wanted to use a non-toxic material. I’d recently seen the Medardo Rosso: Inventing Modern Sculpture exhibition at Mumok in Vienna, so beeswax must have been subliminally in my mind. There was something about the process of melting and transformation that felt appropriate for the works at Cabaret Voltaire. I felt it resonated with Jungian ideas around alchemy and individuation—the idea of creating a tableau of objects that could be entirely melted. There’s an impermanence in their state of being, and the threat of destruction.

How did you connect with Emma Jung, and what did that dialogue open up for you?

The experience of working with her archive and the family was particularly special for me. Together with the director of Cabaret Voltaire, Salome Hohl, we visited the Jung house in Küsnacht and were given a tour of the house and shown the Emma Jung archive by the great-grandchildren, who now look after the estate.

After seeing the work, I felt overwhelmed by the responsibility to do it justice. I began researching more into Jungian ideas and reading the transcripts on Emma’s life and work. Interestingly, my own circumstances changed, and I found myself without a studio, working from a desk at home late into the night in a strange sort of echoing of how Emma worked. There were specific ideas around individual and collective consciousness, fairy tales, archetypes, the unconscious, and dream drawings that particularly resonated with me. The whole process has unlocked a world of ideas that I feel I’m only at the beginning of exploring.

Scrolling through your Instagram, I came across a caption where you wrote: “Even though the show is now open and what you could say ‘finished,’ the works only form partial sentences. It still feels like the beginning in a lot of ways.” Could you say more about that feeling?

I was referring to the show at Cabaret Voltaire. For the first time after the show opened, I felt a sense of loss. I think the experience of making a show in response to the work and ideas of Emma Jung had been so fruitful, I felt a sadness that the journey was coming to an end. I started to reflect on that and began to see it more as the opening of a door instead of the closing. The work I did for the show reflects a broader idea of growth and change that is enduring.

What are you currently working on?

I’ve come back to the UK to work on a solo show at Ginny on Frederick that opens this coming September. I’ll be showing several slide projections for the first time as part of a bigger installation. I’ve set up a studio in my parents’ basement, which feels a bit like a return to teen chaos.