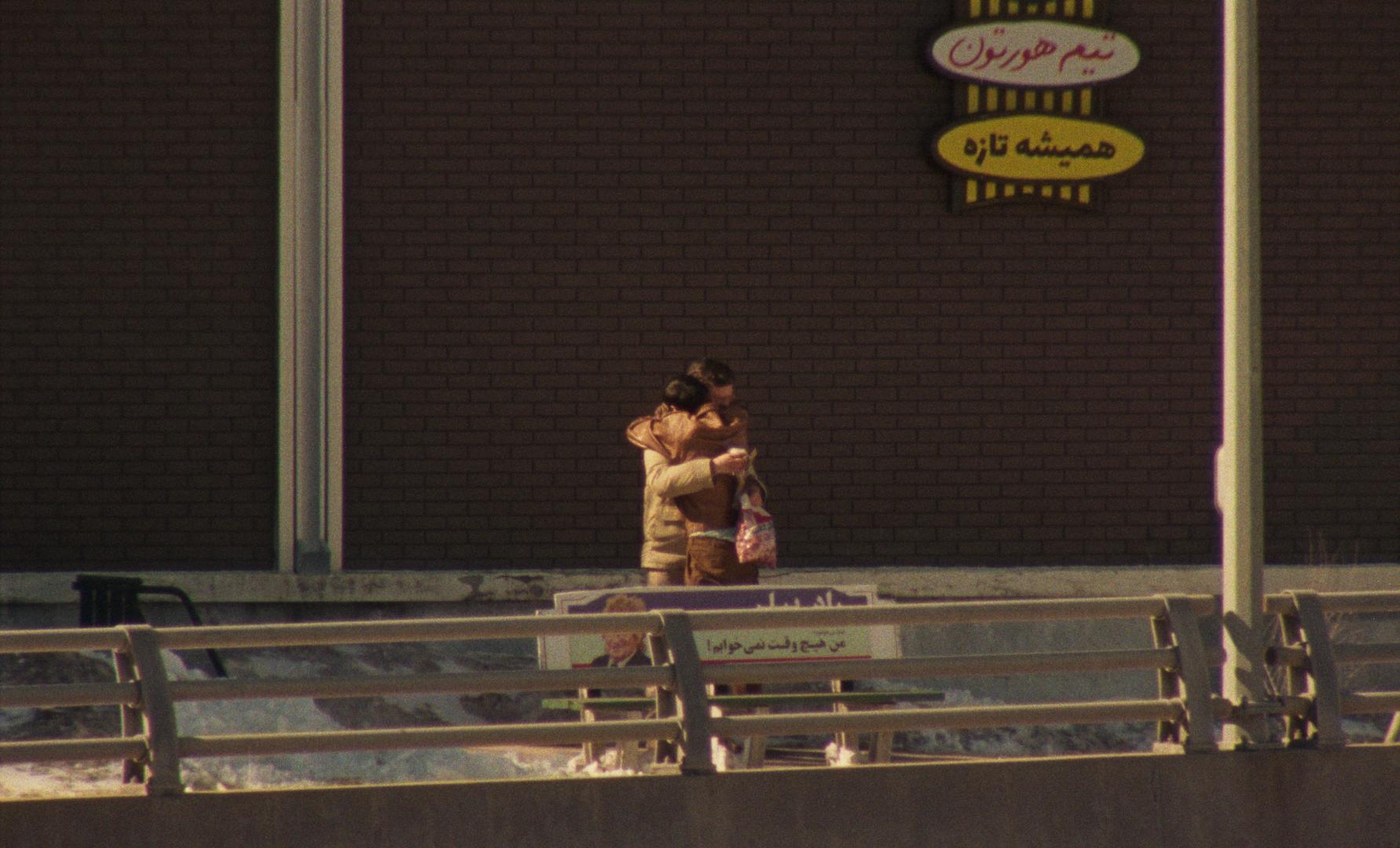

Still from Universal Language (2024). Matthew Rankin as “Matthew” and Dara Najmbadi as “Dara” outside of Tim Horton’s. Courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories.

Matthew Rankin can hardly fit into a single cinematic genre or a tagged box—and that’s exactly the point.

Rankin was born and raised in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and is currently based in Montreal. He was able to etch and carve a space of his own, first of all within the Canadian film scene, blending critical renditions of history and experimental collage with his personal idealistic ambitions that sometimes transcend to a poetic sphere.

He started his artistic journey as a teenager, spending time drawing, with an interest in the inherent values and concepts of human communication beyond the constraints and absurdities of the established structures. While doing so, he was making friends beyond linguistic and cultural borderlines—two evident elements of his oeuvre to this day. This helped him to have a broad understanding of world cinema and a varied cinematic lexicon that as he states contributed to his cinematic “being.”

Although, as an ambitious young artist, he first tried to learn film making in Tehran, where the Iranian new wave of cinema was active, he later graduated from INIS (L’Institut national de l'image et du son) in Quebec. Rankin made waves with short films like Mynarski Death Plummet (2014) and The Tesla World Light (2017), before directing his first feature, The Twentieth Century (2019): a phantasmagoric reimagining of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King's early political life rendered through Rankin’s understating of meaning-making, politics, and nationhood. The film premiered at TIFF and went on to win Best Canadian First Feature. It also firmly established Rankin’s signature style, sometimes described as employing a unique retro-futurist design, surrealist tone, and a deep mistrust of certainty.

In the proceeding conversation, Rankin opens up his perspectives on history, filmmaking, liminal spaces, and his idealistic understanding of the world, while referring to his own creations and other artists/ filmmakers. In particular, he elaborates on his aesthetic takes from the Iranian new wave of cinema by cross-referencing them with Universal Language (2024), a Farsi-language film shot in Canada with Iranian collaborators, exploring the liminal space between cultures, identities, and cities. The film has been praised from the Cannes Film Festival to the Oscars, and by audiences in both Canada and Iran for its uncanny authenticity—an emotional truth that transcends geography, language, and familiar cultural signifiers.

While well-established as a filmmaker, at the heart of his arguments is an authentic refusal to play by film-industry rules. What makes him a voice in the Canadian film scene is not just his unique aesthetics and courageous creativity, but his ongoing commitment to an ideal that is created through genuine friendship and “what thrills the soul,” as he says. This is clearly manifested in The Universal Language, which he co-wrote and created with Illa Firouzabadi and Pirooz Nemati, and where they, alongside many friends, also appear as actors.

In the interview that follows, we reflect on cinematic language, longing, history and politics, friendships, meaning-making, and why art—and not ideology and the financial apparatus—may be our hope for organizing an alternative space in the chaos of the world.

Something I think about is: when you're doing something sincerely, why do you make art? You know, where does that come from? I think that it really comes from a place of wanting to fix something. You know, that reality unanalyzed or unprocessed or unengaged with is, sort of, not enough. I think that if I am trying to avoid reality, it's maybe more that I'm seeking a new reality.

Matthew Rankin, thank you very much for accepting to do this interview. In the oral history project of the Winnipeg Film Group (Establishing Shots: An Oral History of the Winnipeg Film Group by Kevin Nikkel, published by the University of Manitoba Press) you mentioned that you started drawing in your youth and later moved towards animation. Could you please just give me a very general overview of how you started out?

I love to draw, and my parents figured out very swiftly that, if they left me alone with a stack of paper and a pen, I would really just take care of myself all day long. I loved to draw, and I drew all the time. It was really my only way to relate to the world for a long time. When I was 11 years old, my best friend—and he's still my very close friend—was from Argentina, and he couldn't speak English. He only spoke Spanish, but we could both draw, and so we became friends without sharing any language at all. And we were really good friends. His parents also only spoke Spanish, but I was really integrated.

I can't even really think of how we communicated verbally, but we became very good friends very swiftly and we started making little animated films together. Of course, eventually he learned English, and I did learn some Spanish during that time too. But we ended up making animated films together because he had a video camera. They were, of course, very primitive things, but it began like that. It was just a creative gesture that naturally came out of me, and that I wanted to do more and more.

Later, I took a workshop at the Winnipeg Film Group, and I met some of those misfits. There's a lot of very strange people hanging around the Winnipeg Film Group. This would have been in the 1990s. I learned how to use a Bolex and work on film. I liked image-making. I loved making films, just as a very natural creative gesture. It was just a thing that I did without any real ambition or thought about what it would mean.

When I went to university, I went to Montreal and then to Quebec City, and I was making little films all through that time: animation, experimental films. I've made a lot of non-experimental collage films. I was really interested in that. And I’m really interested in history; you take the raw material of the chronology of the past, and you transform it into what we think of as history (which we think of as a science, but really it isn't). There is an artistic operation at play in organizing the past into a beginning, a middle, and an end, and then giving it meaning with character, elaborating an argument, and this kind of thing. So, that became something that I carried into these little films I was making, a lot of which were kind of collage-based, and based on organizing actual historical artifacts to make meaning. At a certain point, I realized I was not a scientist. I was an artist. My relationship with what I was studying—with the past, with history—was an artistic and not a scientific relationship. So, I decided to become a filmmaker and not be an academic.

And my first thought was to go to film school in Tehran. I had an Iranian friend when I was a teenager who showed me these films from the Kanoon Institute.

Which ones?

Well, the first one was Khaneye doust kojast? And then I went deeper, you know, I saw all of the Kiarostamis. I saw all of the Makhmalbafs. Shahid Saless was a huge influence.

That was not from Kanoon, right?

Right, not from Kanoon, but I mean, yeah, like the whole spectrum of new wave.

It began with Kanoon and expanded. All of these films became part of my consciousness, and I really loved this work. I learned that Mohsen Makhmalbaf had started the film school in Tehran.

As a very naive 21-year-old, I had this dream of being his Daneshjoo, so I went to Tehran to see if it was possible. I realize now that I was very lucky to be able to go. It wasn’t obvious that I would get a visa or anything, but it happened for me. So I went to Tehran, and, very swiftly, I learned that his school had closed and Makhmalbaf had left the country.

So, my dream ended, but I had a two-month visa, which I extended for another month. I went all around Iran, and met a lot of really great people who are still in my life, and so it began. It was like this part of my being had a dialogue with Iranian cinema—like an element of my being began. Later, I went back to Canada, and I went to a film school in Montreal called La Institut national de l'image et du son (INIS). That was my plan B, my re-strategizing. It was a very good experience, too. It put me into this world of Quebec cinema, which, of course, is a world that I don't come from. Now, I'm something of a Quebec filmmaker in a way, but not really. Being there sort of took me into that world—which is now another element of my being. I have this sort of dialogue with Quebec. Then, I went back to Winnipeg, and I got down to business. I lived in a very, very miserable apartment, which cost very little and was in a very dangerous part of the city, and I just did art all the time. I spent about two years in that place—three years almost—and I made a lot of things, generated a lot of work. By the end of that period, I was totally exhausted and struggling to get by. Then, I was brought back to Montreal when I took a job there. One job led to another, I continued making my films, and now I am here. I’ve been living in Montreal basically since 2008.

I have kept trying to return to Tehran. I really want my dream. Ila and Pirooz and I have decided, perhaps with the same naive spirit, to retire and start something like an old folks’ home for ourselves in Rasht. This is an ongoing thing. I have tried four times to return to Iran, and each time, something has stopped me from going. Either I couldn't get there, or there's been some sort of instability, or there's been some problem with Canada’s relationship with Iran, but, yeah, I will go. I will find a way. We will all find a way. I know that it’s my dream.

I really liked that part about you and your childhood friend, and the way you explained aspects of human communication. We are having the same experience with my kid. I have a five-year-old son.

There must be daily discoveries, at five years old, right?

Yes, exactly. He was only two when we came to Canada, and we were so lucky to find him a spot in a daycare close to us. Since the first day until now, his best friend is a francophone Manitoban. They are having that exact pattern of communicating without having a fixed, common language at first—and yet, they are perfect communicators.

That's it. Kids really have a way of communicating on, maybe, an energetic level. There's a wisdom to the young brain that recedes from us.

Communication as a means of survival. We humans, in our way of communication, tend to condense meaning into the very essentials, and kids are marvelous at that process.

That's touching, right? It's a beautiful thing. It gives us some hope.

I really liked what you said about drawing and animation. I watched The Tesla World Light and Mynarski Death Plummet, your two short films before your more recent ones.

The same friend from Argentina worked on Tesla with me. We both did the digital animation together, so it's funny.

Maybe you could expand on this, because I want to ask about this drawing and animated quality that goes on in your films, one might claim, up until the Universal Language. I won’t say that it’s not detectable in Universal Language, but they're super obvious in Mynarski and Tesla, maybe still in Twentieth Century.

How do you connect this style to memories or practices from your youth—the practices that we usually don't take as seriously, but that transcend, show up, and manifest themselves in our more professional stages? Do you see this as a continuous thread from what you were doing as a kid or as a youth?

Yes, I think very much so. These are what I love about cinematic language. I've worked in a lot of forms. I've worked in animation, fiction, documentary, non-narrative, experimental formalism, and I love all of those forms. I have a very vast cinematic appetite and I've always been interested in the formalism of what we think of as realism. When I finished Twentieth Century, I was really badly in debt, and I ended up working for the government for a year to get myself out of it. We made films for the National Parks, Pirooz and myself. In fact, we made one set of little films together in Kootenay National Park. I found it really interesting to go out into the world and film—the idea that you could find cinematic language out there in the world where not every frame has to be designed in advance and then constructed—you could just put the camera in front of it and film it. Out there in the world there are frames and there are ways of staging and of angling. There's light, which can be your friend, there's weather that can be your friend. And all of these things can be tools that you use. These were all tools that I had not used, really, up until that point. There was something that I was a little bit—not afraid of—but it was new for me, and I found that it was inspiring. I went in and made a short film, kind of inspired by my Parks Canada experience, about a bench. It's a bench on the side of the road. I filmed it in Winnipeg with my Super 8 camera. It was just me and nature and this bench, and I created sort of a dialogue around it.

I really liked that. I found it interesting to engage with the natural world and, of course, for me, my favorite kind of realism—for lack of a better term—is the Iranian New Wave. Particularly the concern for the artificial nature of realism. In a lot of my favorite films from that era, like in Noon o Goldoon, Nama-ye Nazdik, even Taste of Cherry (Kiarostami, 1999) at the end, there's this moment in which the realism is undermined. They remind you that what you're seeing is, in fact, a simulacrum. It's an artifice in the same way that animation is. Animation very emphatically tells you what you're seeing is not real, but there's a way for you to believe it, and that's something that interests me. That was something we explored in writing and filming Avaze Booghalamoon, and that was sort of by design. It's a movie that's kind of between two spaces and creates its own realism. I think that every film does that, actually. In fact, we do that in our lives too. Like, your kid and his friend are creating an inter-zone and that's actually very easy, but lots of times, the way we conceptualize the world, it's quite a bit different from one another. We think it's hard, but it's actually easy in our lives and in our friendships—it’s very normal. The idea of creating a new structure was something that was exciting to me. I think that there’s a thread you can trace from that very formal work into these adventures in realism. They're still kind of following this idea of how we put reality into images, how we put history on film, how we put the real world into this simulated world and what that means and why that's valuable. I think there's a thread you can trace.

You touched on the concept of reality, and cinematographic experience being a means of creating a liminal space between reality and non-reality—between physics and metaphysics. This is something I confront a lot throughout your filmmaking, no matter how you are presenting it: whether it is the more realistic phenomenon in Universal Language or the more abstracted, experimental form of Tesla and Twentieth Century. I'm not talking about technicality, but the essence of playing in-between, or maybe, you are intentionally trying to avoid reality. This is something I see throughout your œuvre. In Twentieth Century, Universal Language, Tesla, and Mynarski, all of them are connected to some points in history; which become points of departure to the “out there,” but you are intentionally avoiding the written or the existing history. Does that feel right to you?

Yeah, well, that's a great question. I have a couple answers. Actually, I think where history is concerned, I'm very skeptical about the idea of cinema as authentic. I don't know if that’s A) possible or B) even desirable.

You know, this is what I really like about these Iranian new wave films. Like, think of this for a moment: they're not political, the way that films in Iran today are political as, for instance, Rasoulof is. I mean, his films are very emphatically saying, “I'm looking at a political phenomenon and I'm creating a piece of art about that event in this way.” Farhadi is kind of in that zone, too. But these are very poetic films, and I think insofar as they have any kind of political subversion, I think it is in the way that the simulacrum is undermined. These are images, and they're just images, and they create these little poetic frescos. We can relate to them artistically, but any pretense that they are reality is, “I'm here to remind you that that's not what it is,” and I like that a lot. I think that is the danger of cinema, actually, when we seek authenticity in it.

I always say that Steven Spielberg is the greatest living historian of the American past, because he creates a simulacrum that is so irresistible that you believe that it's true in a way that’s beyond just letting yourself go and enjoying the film. You think, “This is what happened. This is reality.” That is the danger of the simulacrum. It can create its own reality, which we can mistake for the absolute truth. Not just the truth in the film, but the absolute truth. And this is a relationship I find really interesting. I think this is why when I have made films that are about a historical figure, I like to be very blatant about the fact that it is an entirely artistic process. I have made no pretense at all about being a scientist. This is me reprocessing events of the past and I'm not trying to convince you that any of this really happened. The arc of the history of cinema has bent towards making things so credible that we forget that they’re not real. And then it becomes propaganda. That is why Spielberg is essentially propaganda: you believe that that's what happened, and it allows you to not question and to not live with any tension.

People watch Twentieth Century, and when they leave the cinema, they often ask me in Q and As, “How much of this is true and how much of it is fiction?” I think that's a really great question, or a really great tension for a viewer to have when they watch any movie, but particularly a historical one that is making some sort of synthesis about the past. You should feel aware of the artifice at work. When you embrace the artifice, and you're very blatant about it, it actually opens up new doors for creativity. It's like when the photograph was invented, painting was transformed. Painting is the arc of art history up until the photograph was again, about creating a simulacrum of reality that was as credible as possible. When the photograph was invented, painting was suddenly liberated. It could be paint. We could explore the expressive potential of paint as a form, we could go somewhere else with it. We could get into abstraction. We could begin to dream, you know?

So all of these things animate my thinking about all of this. Is this me trying to avoid reality? It could be. I am a person with great longings. I don't know. I have very idealistic longings, and I have great longing for elsewhere. I have great longing to step outside of myself, as a person. And this could be a reflection of that, on some level. I feel like you can see echoes of everything I've just said in Universal Language as well. I always say that that film, in a lot of ways, represents reality as much as it is surreal. On one level, it is sort of seeking a reality that we actually know. That movie was made with my best friends, which is a big Iranian community here in Montreal, and we're very, very close. My encounter of Tehran is through my friends, and their encounter of Winnipeg is through me, and, together, we are in that space of the film, and that's actually very normal. I think, through our friendships, we overlap, our realities begin to merge, and that’s a very organic and very beautiful way that we organize the world.

And again, to get back to the way historians organize the past—how we try to put things into containers, and bring order to the chaos—we don't see the world that way. Tehran and Winnipeg are extremely distant places. There are people who want very much to insist on a distance between those two places, but those two places can actually be in a very interwoven proximity in all manner that’s absurd but also very beautiful in some ways. And that's just it. That's just sort of our world. That's just what our lives are like. That's what it is to be all alive at the same time.

I think that the creative gesture is the reason you make art. People make art for different reasons. I mean, some people make art because they are egomaniacs, and want to take over the world, and wear a Napoleon hat. There are filmmakers like this, for sure. Something I think about is: when you're doing something sincerely, why do you make art? You know, where does that come from? I think that it really comes from a place of wanting to fix something. You know, that reality unanalyzed or unprocessed or unengaged with is, sort of, not enough. I think that if I am trying to avoid reality, it's maybe more that I'm seeking a new reality.

Still from Universal Language (2024). Courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories.

Still from Universal Language (2024). Courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories.

Still from Universal Language (2024). Matthew Rankin as “Matthew” in Universal Language. Courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories.

This amazing philosopher of communication, Vilém Flusser, says that human communication is inherently artificial. It's not like bees communicating, for example—it’s not a natural mechanism. The language, sounds, systems of signs that we use are invented. Applying this understanding of communication as production and consumption of a shared value, or shared system of signs, I want to ask you this next question. It's very much in relation to my previous question. You often make use of “sign systems.” They could appear in different forms or in different mediums. It could be architectural spaces, it could be graphic signs, it could be fonts, and so on. This is very evident in Universal Language, because here you're literally living in these warped, different natures that are woven together by you and your friends and collaborators. I'm really seeing it as a kind of carpet weaving, going through this very intermeshed net of threads, and making a new product out of these seemingly unrelated materials. Going back to what you said about reality, how do you see this process? How do you synthesize these different factors to make something new while the elements you are using are not necessarily shared by everyone in your audience?

I think it emerged very much out of a long conversation, first with Pirooz Nemati. We've been chatting about this project for a long time, like, 12 years. Then Ila joined a little bit later. But I would say ninety-five percent of the synthesis you describe, certainly in imagining the world, and putting together the pieces before we begin filming, really just emerged out of Pirooz, Illa, and I amusing each other and coming up with ideas we knew the others would find funny. That's very much an expression of our friendship. Lots of ideas that I might have had by myself, alone in my room, and I only had those ideas because I knew Ila would think it was funny; and vice versa, she would come up with a thing, and it would make her think of me. It was a very peculiar kind of alchemy between us, but one that emerges, I think, out of very close friendship.

When I went to Tehran the first time, I was really struck by the beige buildings and how much they reminded me of the beige buildings in Winnipeg. When Ila and Pirooz came to Winnipeg for the first time, when we were preparing to shoot the film, they had the same encounter—they could see in these beige buildings something of Tehran. It was always about finding these kinds of improbable connections and continuities. That was sort of the rubric—like, there's never one without the other, they're both present at the same time, and we're in two places at once. This sort of reaches an apotheosis when Pirooz and I “switch.” So, we're in two places at once, and we're stepping outside of ourselves and creating a new space. It's not Tehran, it's not Winnipeg, but somewhere at the confluence of both. Figuring that out was about interweaving it. It is absurd, but also beautiful to put these spaces together. Putting these spaces together is strange but it is the world we live in, you know, we're all alive here together at the same time. That's all we are, really, all we are. And that's a way to think of the world as a whole place, rather than as a set of oppositions or fragments, or a set of Berlin walls, or whatever. That was the process, and it very much emerged out of what's normal for Pirooz and Ila, and myself in our lives. It also is an expression of our idealism and our longing for a sort of fundamental goodness, which is a frequency on which we are capable of relating.

There's a shared universal language.

Let me put what I have in mind in two ways. One is about finding the intersections of seemingly two or three different ways, like your Quebecois aesthetics, Winnipeg aesthetics, and Iranian new wave of cinema, overlaying them and finding the knots that are shared between these networks of communication. Or, the other way around, which is finding the shared layer or structure in between these seemingly divided spaces—being at two spaces at a specific time. And then beyond these two spaces—what about being in-between?—occupying a space between all of these, not necessarily being in two spaces at once, but being in a third, liminal space. How do you see it? As a conjuncture of history? Or a third, independent space, made out of these three or four parents?

Yeah, another great question. I feel like, in a way, that is a space I have always lived in and I think a lot of people do. I think that's a source of tension, because there's a lot in the world that tells us that these different spaces are very separate and in opposition, and that living between them is like being pulled in opposite directions. That's a way some people have thought of the world. Lots of artists we can name have created work that is predicated on that, but that's never really been my experience with the world, to be honest. That isn't an aspirational model either. I think a lot of this has to do with the old world of European-style nation-states. I mean, that old model is one that left us with a lot of baggage, to say the least. You think of a space like Canada, for example: What does it mean? Why does Canada exist? Should it exist? If it does exist, does it serve any useful function? And is that useful function even actually good? I think these questions are worth asking. My feeling about it is that, if it serves any function at all, it should serve as a liminal space. It should be a space where we can be free of this old world of European-style nation-states, where we have the possibility to liberate ourselves from that. If it could just be a safe, boring place where we would be mutually dependent, that might serve a real good, an actually useful function. As we know, there are a lot of voices that would disagree with what I just said. There's a lot of baggage that we live with and that we are negotiating, but that is my sort of idealism. This is the idealism that my friends share. It kind of eventuated in this movie, the idea that this is a space that can be constantly renegotiated and reimagined and redefined, and it should be that way. There’re no absolutes. I don't like the world of absolutes. I don't like the world of certainties. I don't like the world where things are like this and like that. I find that very oppressive. Even Twentieth Century was sort of an anti-nationalist movie. The artifice of the national structures we erect—-that is the function of the very artificial set design in that movie—it's the nation building project that is artificial. It could have nothing to do with anything. It's like, when you look at an international border, have you ever visited one?

Yes.

Have you stood on the border between one country and another?

Yes, multiple times.

It's interesting, right? Because it's the same space. A human being has imagined a line here, but it's the same space. It's absurd, you know, it's like the quest to conquer the South Pole. The South Pole is 90 degrees south. It's not a place, I mean. Mount Everest is a place, right? But, the South Pole is not a place. It's something we have imagined. It's a calculation we have made. Mount Ararat is a place, right? The borders of Armenia are different. It's so strange, right? All of these things are just infinitely complicated, and our efforts to contain them to order the chaos often just make things worse. So anyway, I'm a big believer in liminal space. I feel like that's a zone in which we most commonly relate. So yes, the movie is about that.

Thank you.

We showed the film in Winnipeg, Pirooz and Ila and myself went to Winnipeg, and we did Q and As and met a lot of Winnipeggers. Similarly, we did a Zoom in Tehran at this place called Farsh Film Studio, and it was really interesting, because we didn't want to go. Our plan was to make a website that was geo-blocked to Iran only, so Iranians could watch the film for free, but Iranians were much faster than us. The link was leaked or something, and now it's just going around. So that's great. That's wonderful. But we showed it at Farsh Film and what was really amazing for us was that the reaction at that screening, and also at the screening of Winnipeg, were very similar. The Winnipeggers came to us and said, “We have never seen a more authentic depiction of Winnipeg.” And, of course, it's a film that is in Farsi, a language that they have probably no encounter with, for the most part. Similarly, at the screening in Tehran, they said, “This movie belongs to us. It's like you made it directly for us. It's an Iranian movie. We claim it.” And, of course, these are people who don't know each other. It was very profound for us to witness these two reactions and see them overlap. It was actually very moving, because it meant that liminal space was something that was actually alive, and people could enter it, and that proximity was not so far-fetched.

We really made it in the spirit of a very sincere expression of our friendship and our life together. I really do feel that when you go very specific with these things, there's a way in for other people. When you go very specific, I think you do kind of get closer to something universal.

I feel like politics is a way of organizing the chaos of the world. And there are ways to do this, beyond politics, beyond nation. I think art is one of them. I think art can do something that politics can't. And, you know, art can do something you cannot also. It's these tools we use to organize the world that are imperfect, and we sometimes forget that.

Okay. Now I have another question. My personal take on the universal language, which I wanted to share with you, is related to the concept of “wandering” in Universal Language. I'm not sure whether it is intentional or unintentional, but this concept of wandering occupies a good portion of Persian literature of different periods and schools. Heroes, Sufi and Saints, passionate poets, and lovers are constantly grappling with this concept of wandering—going around without any objective or intention at first, but later discovering things. This is almost the same thing that you see in Kanoon films too: some characters are just going around, as if they don't have any home. They're always in the alleys, in the streets.

And a lot of attention is always given by the filmmakers to following a character from point A to point B, the space between is always one that they follow very closely. In the West, of course, it would just be cut. But they really watch people move between the spaces, right?

Totally. this concept of moving, like in Where is the friend’s house?. You literally see it. And in the other Kanoon works, you see the characters running, kids running and reaching something at the end and confronting stuff.

In A Simple Event (1977) by Shahid Saless, too. The amount of running that child does is incredible. At least thirty percent of the movie is him running.

I totally believe that this manifestation is not random in the Iranian new wave. It's feeding on that heritage of Iranian literature, concepts, mythology, and its wandering heroes. So, how do you see that in Universal Language?

Yeah. It's true. That it’s about the language itself. The idea that there's something next to the action which is perhaps more worthy of our attention than the action itself. There's one scene in Noon o Goldoon; Makhmalbaf is in the car speaking to the young man who's going to play young Makhmalbaf, and Makhmalbaf is doing all the talking. He's the one speaking, but the camera stays only on this young man listening to him, and I really love that. It was something that really struck me, because, of course, in the West, it wouldn't be like this, right?

You would have the speaker as the center of attention.

Well, that's right, exactly. That again comes back to this obsession with the individual and the active protagonist. You know, the idea of the protagonist as an individualistic figure, and the camera supporting that. You know, when I speak, the camera cuts to me. When you speak, the camera cuts to you and so forth. I really liked this interest in the person who is listening. In a lot of films from that era, sometimes the camera moves away from the center of the action and looks at something adjacent. Like in Nama-ye Nazdik, the opening sequence is actually very dramatic—it's the moment they go to confront Sabzian. He's taken away by the police. It's a very dramatic incident, but the camera stays with this taxi driver who has driven them there. He's just waiting outside. The camera stays with him. This is something that I find so beautiful. Sometimes, you'll hear a conversation, but you'll only see the building in which that conversation is taking place. You might hear it very close, but you're only seeing the building from a great distance. You don't even see the characters at all. These are things that I find very interesting, this idea of the peripheral gaze. And, this was something that we wove into the fabric of the story [of Universal Language] itself. The characters walk away from dramatic moments, and they explore some other phenomenon. It’s also a way of tracing the interconnectedness between all of the characters. This might be the center of attention in one life, but in another life over here, something else is the center of attention. It's a way of weaving it all together. I think it's also a liminal zone, the idea of moving from point A to point B, and that space between.

Abdelmalek Sayad, the Algerian-French sociologist, has a concept about the people who are, as you said, dragged in-between two spaces, maybe two geographies, like immigrants, like displaced people.

I'm very much trying to apply this to displaced cinema, like cinematographers who have been displaced from their community. Sayad, who was a displaced person, developed this beautiful concept of la double absence. He was from Algeria, and then he went to Paris and became a social scientist. He was always wrestling with this in-betweenness. He was not French, he was not Algerian, and he couldn't abandon any of those identities, and he couldn't fully attain them, either.

So, he coined this concept of la double absence. He says that people of this nature—I consider myself to be one, and you kind of remind me of the same—are ultimately always absent from both spaces. Being in-between, you cannot fully belong to your source community, but nor can you fully belong to your host community. I've come up with this—maybe the opposite—concept of the double presence, as an answer to the longings of double absence. Your film is kind of a double presence, as it at least tries to portray an idealistic double presence as a response to that double absence.

That's a beautiful way to put it. I like that very much. It's true. We have sort of gone down a path. We see the world in terms of oppositional paradigms and that is one where this double absence could become something that is very troubling. There's a lot in our world to encourage and reward that way of thinking. But I think that we can also name, as you just have very eloquently, spaces in which that's actually a very beautiful, very comfortable space to be in, and that it can be a kind of home. It's a kind of home in which we can all belong, in a very real way. And it's not really quite as far-fetched as we might imagine it being.

But I like that very much. It's about that. I mean, we're always very insistent that the film is not about any one of these spaces. It's not trying to assign specific meaning to any one of the three spaces that are blended, but to create a new space at the confluence of all of them. That space can be a home, and it can represent a broader notion of human belonging than what three separate spaces might propose in themselves.

You're interested in history, and that's so evident in your works. You have a good command of history, and you’re aware of your own critical views on history. I can imagine that you have the same critical points on politics. One sees the propaganda posters in Universal Language, and sometimes they're funny, as the visual graphics are kind of mixture of Soviet propaganda, the political posters of Iran, and the wall murals of Iran, and the politics of Manitoba. Based on these, I want to ask: what is your relationship to politics? How do you criticize it? How do you observe it? And how do you render it?

I think about it in a similar way to the way that I think about nationalism and statehood. Ila Firouzabadi and I are working on a docu-fiction. We began this before working on Universal Language, and we have to finish it soon. It’s about Esperanto. There’s this idea of artifice as a tool. Like, you and I are speaking English. English is a lingua franca. But there's a very evil reason for that. I mean, we're using it in a non-evil way, you and I, but, but still, the reason we are using it is quite sinister. So, the idea of Esperanto is that if we don't share a mother tongue, we would speak to each other in Esperanto. It's a very beautiful idea, because being an artificial language which belongs to no one, there’s no nation or imperial ambition that is imposing that language. We're using it simply to communicate, because we believe that we all belong, and this is a zone and a language that can belong to all of us. It belongs to no one group, and therefore belongs to everybody. So I think of myself as an internationalist. And what I like about Esperanto is that it's not driven, really, by any ideology beyond a belief in the fundamental goodness of humanity. And that's what I believe in. I don't ascribe to any political party. I'm not a partisan political operator. I don't ascribe to any ideology of any sort or spirituality. I don't. I did grow up in Winnipeg, so I live with an irony that cannot be removed from my brain, and, in a way, that makes it impossible for me to absolutely believe in any absolutes. Yeah, I can't believe in any absolutes. I can't be certain of anything. I have no certainty. So, that's, I guess, my general answer.

But more than that, there's something beyond this. I feel like politics is a way of organizing the chaos of the world. And there are ways to do this, beyond politics, beyond nation. I think art is one of them. I think art can do something that politics can't. And, you know, art can do something you cannot also. It's these tools we use to organize the world that are imperfect, and we sometimes forget that.

Yes. Thank you very much for answering my question, though I did not mean to ask about your personal political inclinations, but more about your understanding of politics in your artistic production. For instance, there is a certain level of criticism when I look at the propaganda-like posters of Universal Language as if you're mocking the superficial political messaging, or promising, and campaigning. In this regard, what is your relationship with political power when you're showing it?

There are two, I guess, political murals in the film. They were both designed by Sarah Shoghi, who's a brilliant graphic designer. She lives in Toronto, she made those and she also made the 500 Riel and the portrait of Louis Riel in the classroom.

I think those are the only political kinds of texts that are adjacent to or a reworking of political signs, signifiers. I think that in the case of the two murals, it is making fun of Western style of conservative politics. There's something very interesting that Samira Makhmalbaf said once. She said that, in her opinion, in Iran, artists must contend with political censorship, while in the West artists must contend with economic censorship. I thought that was an interesting analysis. I'm not trying to say they're the same. I don't think she was trying to do that either, but there is something about some sort of…

Maybe goalkeeping?

Exactly. I mean, look at our current situation; we're in an election in Canada right now, and people speak of the economy in a way that I think previous generations might have spoken about society. We don't actually, in the West, necessarily live in societies anymore. We now just live in economies which benefit not most individuals, but certain individuals. So, this idea, you know, “A strong economy helps to prevent feelings of worthlessness.”

It's really good. I like that.

Communicating, you know—that written statement is very Soviet, very bold and confronting.

You know, our inspiration was North Korean propaganda!

I think maybe one of the fantasies the West has about itself is that we're a democracy, and we don't believe in censorship, but we actually do. And so that was sort of a way to make fun of that…

I really loved what you said about this new economic society. I would even go a bit further and call it a financial society, because it’s like a full-fledged financial system rather than a classic economy. As if we live in financial spreadsheets.

That’s right. And our politics and our politicians manage the population on behalf of the financial institutions, who are not beholden to us at all, who follow the cruel logic of the market.

We made this on a small scale, so we had the liberty to just follow what was meaningful for us. [...] I don't have commercial ambition. I don't even like being the center of attention. I don't like that kind of thing. I don't like red carpets, I don't like going on stage, I don't like awards, I don't like film competitions. I don't like that stuff. Personally, that's not why I do anything. I do things because I love art, and I love working, and I love my friends.

Experimental filmmaking, despite its financial limitations, is always a safe zone for creation with its own community, language, and intimate modes of operation. If we consider Universal Language a transition to commercial filmmaking—not in the content, but production—then, based on what you just said about financial society being some sort of goalkeeper, how do you find this affecting your creative process? They may not censor you in political terms, but you know they can put filters and limitations on the way you are working.

I don’t know if anyone thought of this as a commercial film. I mean, we were not thinking about that at all. This is an unusual film, and in a lot of ways it’s strange that it exists. In making it, my friends and I were really just following what thrilled our souls.

I don't mean commercial in terms of form, language, and production. It's not a Hollywood movie in terms of distribution and reception, production, or the economy of filmmaking. You're not relying on $100,000 budgets, when you were making Universal Language.

No

I mean experimental in terms of finances and economy, when you want to make a bigger thing which relies more on the commercial market…

I would say that we didn't have a large budget for this. The budget was small enough that nobody really cared. They were sort of like, “You do this.” I mean, I had made a lot of films, and they had done well at film festivals so I was able to go to them and say, “You know, we believe in this. And we think it will be good.” We were able, I was able, to make a case for them to give us a budget, but it wasn’t high stakes for them. They were not stressed out about giving us this amount of money, and they left us alone. If you have a lot of money, they will get nervous and follow you very closely. Honestly, no one believed that anyone would watch it, and they were fine with that. It was an investment that they could recoup just based on virtually nothing. But what happened was, well, it got into the Cannes Film Festival and won a prize.

And you literally went all over the world with it, all the way to the Oscars

On paper, no one would ever believe that. It's also a thing that people connected with it, an improbable film for people to connect with. It is abstract, and it's unusual. It's not structured in any kind of commercial way. It’s slow, but people connected with it. Even commercial people who try to predict these things can't do it. Even in Hollywood with enormous budgets and focus groups and everything, they think, “for sure this is going to be a huge film.” Even then they fail. You never really know, but that's the thing. We made this on a small scale, so we had the liberty to just follow what was meaningful for us. And I'm not a filmmaker that ever really thinks about those things. I don't have commercial ambition. I don't even like being the center of attention. I don't like that kind of thing. I don't like red carpets, I don't like going on stage, I don't like awards, I don't like film competitions. I don't like that stuff. Personally, that's not why I do anything. I do things because I love art, and I love working, and I love my friends. That's why I'm a filmmaker. So, none of that was part of the equation at all, but as we go on, because the film has had some success, and there's a lot of eyes on it, and on me, and my friends, it's possible that there might be bigger budgets that are available to us now. And then we might be beholden, but you never know. I still want to do it the way I like to do it.

So, you don't see it as a restricting factor, right?

Well, yes. It is. The more money you have, the more restricting it will be, for sure. That's always true. Of course, there are people who will object to that. For example, the Conservative leader does not believe in cultural institutions and would, if he had the liberty to, destroy something like Telefilm Canada or the CBC, the National Film Board, or whatever. All of these things would be gone. In his mind, which is driven entirely by the logic of markets, culture does not serve any public good unless it is a commodity that is consumed in a very capitalist way. So, this is a fragile thing, even with this small budget, where they leave me alone, it's very fragile. And for us—Ila, Pirooz, and myself—we have no interest in Oscar night, or winning prizes, or anything like that, but it’s a game we must play. Because then Telefilm Canada can go to the market-driven conservatives who might be the government, and say, “Look, this isn't a waste of time. Look, it has ‘real world recognition of value.’” So, it's a game. You have to play this game. It's like this weird dance. You know, we all have to do this. We have to maneuver around these systems of power. So, yes. to answer your question, in a very circuitous way, even where they don't really control us too much, we're still beholden to the system of power which we are in.

So, speaking of politics, I've heard that you're working on an archive of the Conservative Party.

Yes, yes.

So, could you just give me some more information? I heard this and I immediately thought that you would not be the best director for the footage.

I think we were extremely lucky. I think some intern or some low-level person who had, nonetheless, the power to sign the release, did that without Googling me. So now we have it. It’s all legitimate. I showed the letter to the lawyer, the lawyer said yes. But there are archives in their archives—I'm sure that in the Conservative Party, there might be some holdings that are…

Of course, they always have different levels of access…

But what I'm using are the archives that the Conservative Party had left at the National Archives of Canada, which is an enormous amount of material, and it's not them managing it. I think that if I tried to go into their office and rummage through their boxes that would be a different story. But what they have consigned to the National Archives, I have access to that, and it's an enormous amount of material. So yeah, I'm kind of returning to my roots in collage. So yeah, collage film, but it does tell a story, and it's quite funny and it's a very complicated piece.

I'm editing it now, doing a little bit of filming as well. Ila is building some props that we need. It is still kind of hybrid. It’s about 95% archive, but the archives are transformed to a very large degree and animated, in some cases, and fictitious elements are brought in. There's a lot of surrealism, but it does tell a story that I can argue historically—like a historical argument.

So, you see politics in history? These are two things that you engage with in your own way. A lot of dark comedy, a lot of intervention, and a good pinch of collage will be involved. Can we expect such a thing?

Yeah, it's pretty funny. It's fun making it. We'll see how frightened the lawyer becomes when it’s done.

Just going through the archives, it’s a lot of hard work.

Well, this I've done, but it never really stops. I've edited about 72 minutes, but the film will be about, I don't know, 100 minutes long. It's a very complicated thing to edit, and its grammar is very strange. It’s sort of a documentary, and it's making a documentary argument, but the language is a very surreal and satirical prism through which the material is fed. And, yes, it's a bizarre piece. They can't—the lawyer can't really compare it to another film. And that's a problem, because they can’t say “Oh, well, this precedent was set by this movie, they did something similar. So, we have the confidence that this one will be the same way.” So, it's tricky. It might get mired in that kind of trouble. But for now, I'm just making the movie I want to make. I'm just following what thrills my soul, and we'll see what happens.