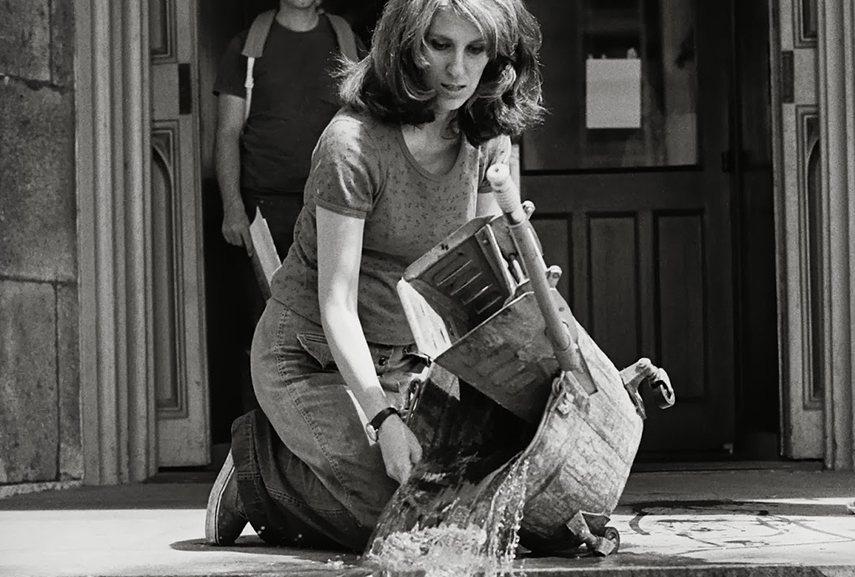

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Maintenance Art Performance Series,1973-1974. Sourced via

In his introduction to Permanent Red, first published in 1960, John Berger offers an approach to art criticism that begins with a simple question: “What can art serve here and now?” Berger was a fervent Marxist, and his style of criticism reflected the social and political concerns that dominated his work. He believed, among other things, that the 20th century was “pre-eminently the century of men throughout the world claiming their right to equality.” When he looked at a work of art he asked if it helped or encouraged people to know and claim their social rights. He didn’t mean this literally—such an approach, he said, would result in a sort of propaganda. Instead, he thought a work of art could allow a viewer to understand the world differently—to retain and remember an artist’s way of seeing the world. This, he said, helped a viewer to understand that they were in relationship to the world—something Berger believed held the promise of action. Through this lens, art is a means of unlocking a person’s potentiality—the possibility of being awakened to one’s relationship to the world and then, with eyes open, participating in it.

I’ve had Berger’s question on my mind lately: What can art serve here and now? The answer depends on the conditions of the here and now, which, of course, are myriad: climate change, extreme inequality, a loneliness epidemic, mental health issues, wars, extremist and authoritarian politics, and distrust of institutions. But from this heap, a theme emerges—something the writer and filmmaker Astra Taylor refers to as insecurity.

Taylor has spent years studying inequality. In her 2023 Massey Lecture, The Age of Insecurity, she argues that we are in an age of manufactured insecurity, which she defines as “a mechanism that facilitates exploitation and profit and is anything but inevitable.” Insecurity, she writes, “describes how inequality is lived day after day. Where inequality can be represented by points on a graph, insecurity speaks to how those points feel.”

Early in her book, Taylor notes that some level of insecurity—something she identifies as existential insecurity—is inevitable, a part of being alive. Manufactured insecurity, on the other hand, is something our political and financial systems impose on us by choice. Though their origins are different, their remedies are arguably the same. Security, in whatever form it might take, “can only be achieved with effort. That is to say, with care.”

If the 20th century was, as Berger says, a century of people understanding and claiming their rights, the 21st century—at least what we know of it so far—can be thought of as a time when people, animals, ecosystems, and social systems are recognizing and vocalizing the importance of care. Under the weight of mounting insecurity, which, as Taylor notes, reaches across the wealth spectrum, the importance of care, as both an alternative to insecurity and a potential antidote, is becoming abundantly clear. We can see this in the demands of marginalized communities, in the climate-related disasters that come with increasing frequency, and in the buckling of publicly funded systems like health care and public infrastructure. We can see it in housing and mental health, both of which are now often described as crises. And we can see it in the waning trust in institutions like the media and government and the rising trust in corporations like Amazon. This insecurity is not distributed equally—it never is—but the absence of care is a burden we will increasingly all come to bear.

According to Berger’s theory of criticism, the question I should ask is: Can a work of art help people recognize and realize their need—and perhaps more crucially, their responsibility—for care? Surely some can and do—many artists have been grappling with the question of care through their work for some time. But there is an important distinction to be made between a work of art and the work that goes into art—the labour and working conditions that surround it, shape it, and help bring it into existence. In a time of systemic critique—another defining factor of our age—should we limit Berger’s question to art, or can we stretch it a little and apply it, too, to the systems around art, the structures that fund it, support it, and keep it alive?

In late 2023, a meme by the artist Cem A. started to make its way around the internet. The meme shows two kiosks, each occupied by a single attendant. Above the first kiosk is a sign advertising “exhibitions about care.” Below it, the attendant is talking to a patron who stands at the front of a long line that runs to the end of the frame. Above the second kiosk is a sign that simply says “care.” Beneath it, the attendant looks forlorn, sitting with his head in his hand. No one is in line to talk to him.

One way to read this meme is through the lens of attention: maintenance and care work is boring, as Mierle Laderman Ukeles famously wrote. Why would anyone line up to hear about it? But another interpretation—one that is relevant to art, academia, government and any other sector that espouses the importance of care—is about the distinction between presentation and practice.

Care is easy to hold up as an ideal, easy to talk about, and easy to insert into marketing packages or corporate mandates. It is much harder to put into practice, in part because it is work that must be done over and over again. In the face of insecurity, which emphasizes scarcity and disincentivizes basic human traits like generosity, kindness, and concern towards one another, care becomes an even rarer practice.

In her book, Taylor recounts a story about a bakery that for years looked the other way when employees took home unsold loaves of bread. When the bakery later faced the prospect of closing, the owners installed cameras to catch employees taking bread and then fire them, saving many thousands of dollars on severance and pension pay.

Taylor notes that the bosses in the story—who literally fired staff for taking bread, perhaps one of the most clichéd bad guy crimes there is—are clearly the antagonists, but she also reminds us that the bosses, too, are living with the insecurity that contemporary capitalism imposes. Like so many employers who fire long-employed staff months before pension eligibility, the bakery owners were responding to the zero-sumness imposed by manufactured insecurity. Taylor is not endorsing their behaviour, she’s not trying to redeem them; she’s simply pointing out that they were responding to a stimulus that social structures impose—one that encourages self-interest.

This kind of insecurity is rooted in the fabricated idea, implicit in capitalism, of earning a living—which is distinct from working, participating in, or contributing to a community. In an interview in New York Magazine, the polymathic architect Buckminster Fuller said, "We must do away with the absolutely specious notion that everybody has to earn a living. It is a fact today that one in ten thousand of us can make a technological breakthrough capable of supporting all the rest. The youth of today are absolutely right in recognizing this nonsense of earning a living. We keep inventing jobs because of this false idea that everybody has to be employed at some kind of drudgery because, according to Malthusian-Darwinian theory, he must justify his right to exist.”

many of the engineers of our social and political systems use care as a rallying cry—an empty one that only thinly veils the pursuit of profit and the perpetuation of insecurity. But when we compare words to actions, there is little care to be found

Fuller said this in 1970. In the years since we’ve only gone in the other direction. It is harder than ever for most to earn a living, and many who do are stuck in what David Graeber defines as bullshit jobs. In 2013 Graeber wrote, “Huge swaths of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks that they secretly believe do not really need to be performed. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul.”

Another scar, perhaps a mirror of the one Graeber describes, is that which marks so many care and maintenance workers—one of the few groups who do not perform bullshit jobs and who cannot truly be replaced by a technological breakthrough. People in the maintenance and care sector often make little more than minimum wage, meaning they have to work longer hours or multiple jobs, robbing them of the care that they are expected to employ. Many who adopt a conservative capitalist perspective argue that (further) privatization is the answer to solving these woes. We only need to look to our southern neighbours to see how well that has worked out. Yet these challenges persist, in part because many of the engineers of our social and political systems use care as a rallying cry—an empty one that only thinly veils the pursuit of profit and the perpetuation of insecurity. But when we compare words to actions, there is little care to be found.

It seems a bit entitled to now pivot to artists and artistic practice—I tend to believe that only when maintenance and care work is properly funded and supported can the rest of a society truly thrive. But like Berger, I believe art has a role to play in the here and now. I believe it can poke holes in what we understand as inevitable—to see that we are in relationship with one another and to act on that knowledge.

Artistic practice has a particularly prickly relationship with the idea of earning a living, in the Fuller-esque sense of the word. The need to turn a work of art into something that can turn a profit influences how artists work and what kinds of work get made. (If we follow this to its natural conclusion, do we reach what Graeber might describe as bullshit art?) Berger believed the relationship between art and capital was unhealthy, arguing that “private property must be destroyed before imagination can develop any further.” Still, the need to earn a living through capitalist means persists.

In Canada, artists tend to hobble together an income through a few channels, including arts employment, often through the academy or not-for-profit institutions; grants and public funding, which are never guaranteed; commercial sales and representation, a small portion of the Canadian arts landscape which excludes artists who do not, in the strictest sense, produce something that can be bought and sold; craft sales and fairs, which pose the same problem as commercial spaces; and fees for exhibitions, artist talks, and other public appearances. Other artists, who cannot make ends meet through some combination of the above (and many who can), are relegated to making work in the off hours, after day jobs or before night shifts, fuelled, presumably, by some bottomless and unwavering passion. In short, an artist's income is often precarious.

These dynamics steer many artists toward certain career paths. The growing role of the academy in arts employment, for example, has led to an increase in post-graduate programs in the fine arts. One byproduct of this trend is a feeling that one must have a graduate degree in art history in order to engage with work (something I’ve heard repeatedly from people who are interested in the arts but feel excluded from it). At the same time, artists who might have hoped to find stable employment in the academy—a sense of security—often find themselves in precarious adjunct teaching positions, saddled with student loans, trying to care for the needs of students while they themselves struggle to make ends meet.

Similarly, the importance of public funding—which, compared to many countries, is generous in Canada—shapes what kind of art gets made. The importance of appealing to a jury, of proposing a project that must appeal to a group of adjudicators before it is even begun, can have an implicit—or in some cases explicit—impact on who gets to make work.

It may sound as if I’m criticizing public funding or post-secondary education. Not so. I believe there is value in both. I raise these issues because I believe artistic practice has deep and important value. But the insecurity that threatens other sectors threatens artistic practice as well, and I question the capability of the systems and structures around art, as they currently exist, to lessen insecurity, to do the ongoing work of guarding against it, and to instead elevate the practice of care.

With that in mind, I’d like to return now to Berger’s question, or the question I’ve adapted from Berger’s methods: In the here and now, can art and the systems that support and shape artistic practice help people recognize and realize the importance of care? I believe they can. As I’ve noted, I believe art can push on the edges of what we understand to be possible. I’d like to engage, then, in an exercise intended to blur the lines between artistic practice and systemic critique. I’d like to try and imagine something more.

Some years ago, I was speaking with a Swedish citizen who told me that Sweden had a system of military conscription—a fact I was until that point ignorant of. I asked my Swedish friend about the program, expecting him to critique the policy, in part because in my mind I was critiquing the policy. Instead, he told me that he was in support of the program. In his telling, it offered citizens a training process that many found invaluable, and which included basic skills like maintenance and first aid. Additionally, he said, it created a sense of civic responsibility among citizens, bringing people from various walks of life together. To my surprise, I found myself convinced by what he had to say.

As with art, a healthy civil service can awaken the potentiality in a person and in a people. It’s this belief that led me to the idea of an artist civil service—a program designed to both bolster the maintenance and care sectors and to help support and maintain the arts.

In the years since, I’ve become a firm believer in the idea of a mandatory year of civil service, not in the military but in fields related to maintenance and care work (child care, senior care, sanitation). The benefits that my Swedish friend noted are ones to be championed. Developing and implementing a system that encourages those values, one that connects people to the social and civic infrastructure that makes communal living possible, is something I’ve come to see as essential. As with art, a healthy civil service can awaken the potentiality in a person and in a people.

It’s this belief that led me to the idea of an artist civil service—a program designed to both bolster the maintenance and care sectors and to help support and maintain the arts.

The program would require participants to work twenty hours a week in one of various public sector jobs—sanitation, child care, elder care, health care, janitorial services, gardening, groundskeeping, snow removal, carpentry, art instruction, community engagement, and so forth. Each position would include training, but jobs could also be tailored to the skills of each service member. (It’s worth noting how many skills and abilities artists acquire through artistic practice: painting, design, carpentry, photography, textiles, metalwork, horticulture, beading, linguistics, coding, engineering, architecture, social work, oral and written communication, and educational instruction, to name a few.) All participants could then spend the other twenty hours of their work week—or more if they chose—on artistic practice, perhaps even in a studio space developed in one of many underused government-owned buildings (cultural land trusts are a practice that would pair well with this proposal).

For all this each member of the program would earn a living wage.

The first question many will ask in response to this idea is, how will this be paid for? The question, though not irrelevant, demonstrates both a lack of imagination—many economists have developed policies that could fund such a program—and the imposition of manufactured insecurity, once more, on ideas of care. This might seem like a dodge, an attempt to avoid the question most decisions in capitalist societies hang on. Instead, I see it as a reversal, an attempt to allow alternative modes of thought to expand what is fiscally possible, rather than to impose fiscal limitations on the imagination and on the possibility of change.

But it’s also worth noting that organizations and governments are already experimenting with the financial feasibility of similar programs. In Ireland, 2000 artists have been included in a pilot project offering a universal basic income to artists for a period of three years. In Vancouver, 221A has developed policy approaches, including the idea of the Cultural Land Trust, to offer generous fellowships and low-cost studio space to artists. These experiments show that many alternatives are possible.

In addition to fiscal questions, there will be administrative ones. Almost any program that tries to be inclusive is also, by nature, exclusive, and some people will be left out. Creating systems for making and managing those decisions would not be easy.

There is also the question of equity. Many who work in care and maintenance industries do not now earn a living wage. Why should they be excluded from such a privilege? My answer: they shouldn’t. Though I remain mixed on many proposals around universal basic income, I believe it is an option for bolstering the wages of people who work in the service sector and who work in fields related to maintenance and care. An artist civil service has the potential to support artistic practice and to support care and maintenance work at a time when it is badly needed. But it also has the potential to offer an alternative for other sectors as well. People who do important jobs and are not fairly compensated should not be left out.

But my initial question was about art: What can art serve here and now? I believe the answer is service and care, and I believe experimentation and imagination—tenets of artistic practice—can help us get there. What I’ve offered here is more of a question than an answer. What could be possible? Many other questions—material questions, administrative questions—will follow. They will take work and time to answer. What I offer isn’t yet an answer. It’s a beginning.