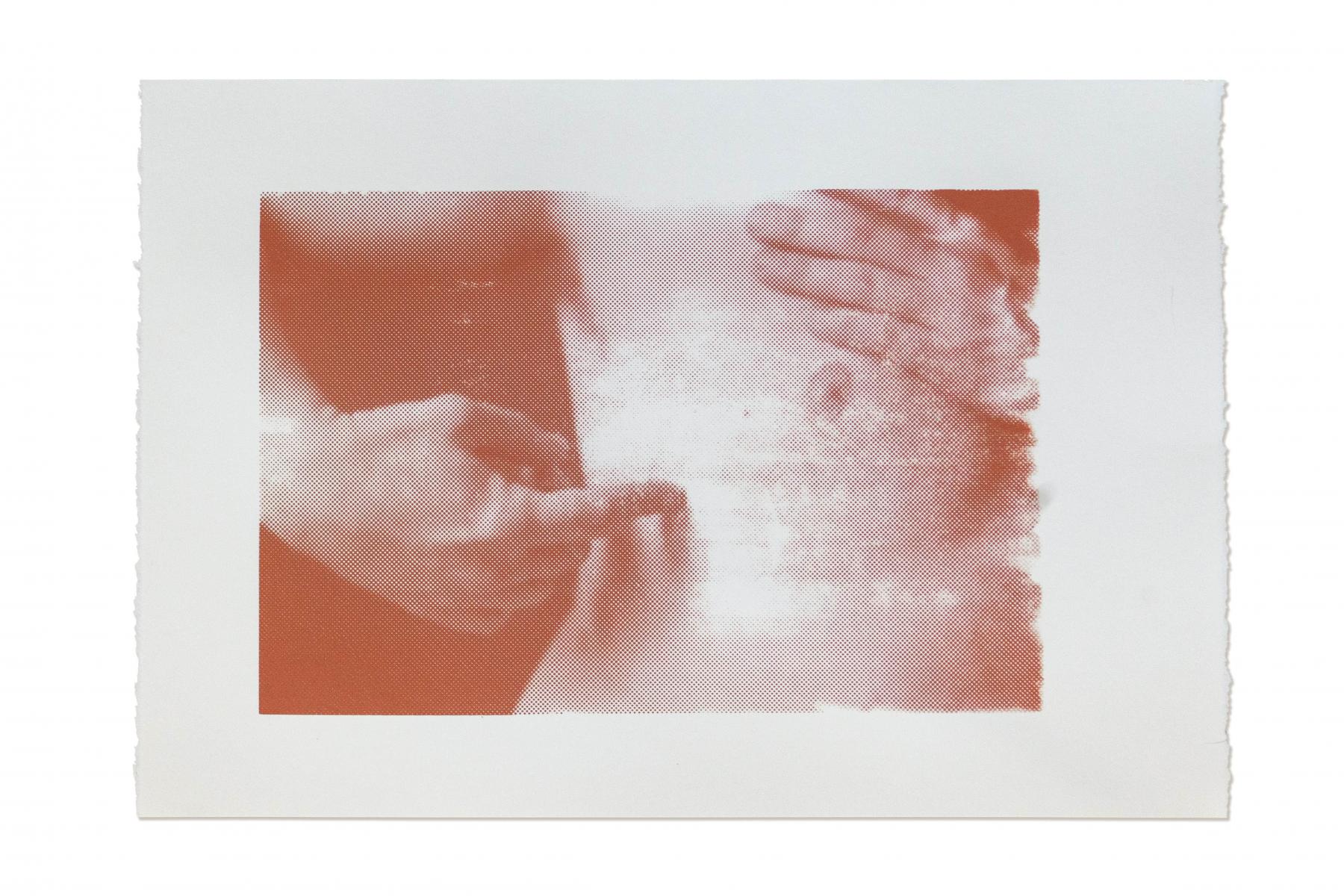

Roman, 2025 by ESO MALFLOR from Swell Series

I met multidisciplinary artist ESO MALFLOR in Minneapolis while I was an artist in residence at Dreamsong Gallery in 2024. When we met, they told me about their land-based practice and recent experiments with clay. I also had recently started working with clay, making small ceramic sculptures to 3D-scan into a virtual world, while MALFLOR had been using clay in drawing and performance. They described their performance Equilibria (2023), in which they covered themself and the performance space with a full tonne of clay. Accompanied by violinists Arlo Sombor and Creeping Charlie, they made micro-movements over an hour while the clay slowly flaked off. Intrigued to learn more about their practice, I visited their studio tucked above a rummage shop on an early spring day in March.

At the time, MALFLOR was preparing for their show, The Earth is a Body in Transition, at HAIR + NAILS. Their small workspace was packed with scavenged materials, burnt remains of buildings, carved charcoal, and conglomerations of bones and nails. While sharing insight into their meditative processes, they talked about the inspiration they took from emergent patterns in nature and the affinity between forces like symbiosis and mutual aid. In a spatial arrangement that mirrored these concerns, the majority of their studio space had been dedicated to the PAIR (Pilot Artist in Residence) program. A project that MALFLOR started with studio mate Witt Siasoco, and supported by Midway Contemporary Art's Visual Arts Fund, PAIR provided free studio space for emerging artists.

During the eventual run of The Earth is a Body in Transition at HAIR + NAILS, I was back in Winnipeg. MALFLOR took me on a virtual tour of the exhibition, guiding me through the space and letting me get up close to details in their works like patterned pyrography and stones embedded on the frames of drawings. The show's central body of work, Controlled Burn, is a series of drawings on wood that explore the idea of preventative harm. Using soot, clay, and soil, the semi-abstract works draw links between Indigenous forest management practices, gender-affirming surgeries, flag burning, and the fires of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in Minneapolis after the police murder of George Floyd. The drawings harness the cleansing power of fire while placing political protest and trans community care in the elemental realms of water, air, and soil.

Other works, like MALFLOR’s KROPP/BODY/CUERPO photo series, provide glimpses into practices of engaging with presence in the face of loss and death. Created on their familial land in Northern Norway, the photos document forms on the landscape created by the artist tracing their body with deadfall sticks, then photographing the shapes after a year of weather and animal interactions dispersed the materials placed by the artist. The images allude to the emergence and entropy of all bodies, from the cohering and breaking apart of the clouds above our heads to our own eventual disintegration.

During this moment of increasing fascism, genocide, and environmental devastation—and the fear-based dissociation that it breeds—MALFLOR’s work offers a strained solace, compelling me to sit in connection to the earth and other bodies. What follows is a few conversations between MALFLOR and I, held over Zoom in February 2025, during which we talk about silkscreens made with serous fluid from top surgery, Ana Mendieta, collecting rocks, and emo music.

I've come to this place of understanding that a lot of the lens through which I understand the world is a very trans lens. There's transness and queerness throughout nature. Things are always moving and are always in transition because we are bodies on this earth; there's constant movement, even underneath our feet. Even though I'm sitting still right now, the earth is on a tilt, on an axis, and spinning very slowly.

Can you tell me a bit about your background and how you came to make art?

I was born and raised in Houston, Texas. I first started getting into art through music when I learned how to play the guitar and I became really obsessed with learning how to play every Linkin Park song because I was obsessed with them when I was little, like, to a concerning point. I was always writing lyrics in my journals in class, not paying attention. I was a very introspective child. I started taking lessons on piano, bass, and drums. In high school, I started taking a darkroom photography class. My teacher had just graduated from the University of Texas at Austin with her MFA, so she was very young. She's been a very important part of my life, like a mentor and guide. She really taught us at a college level. We were lucky. We had access to this dark room facility, which I don't think a lot of high schools had for their students. [My teacher] really took a vested interest in me and a handful of other students who took it seriously. She showed us Ansel Adams, Edward Steichen, Sally Mann, Man Ray, and all these photographers who were really inspiring to me at the time. I started taking visual arts seriously through that class. But mostly, I was interested in alternative processes and in being hands-on with the material.

I also had a moment in my artistic journey where it was thwarted for a second because my parents didn’t want me to study art. They didn’t want to pay for it and were worried I wasn’t going to get a job or any money from it. So, they suggested I study to be a pharmacist because I was a certified pharmacy tech right out of high school through a health course. And of course, they saw a way for me to make a career. I was good at it, but it was boring. Then the more I worked in pharmacy, the more I found that I highly disagreed with the pharmaceutical industry. After my first semester at the University of Houston in a pharmacy track, I had a mental break where I was like, “I have to be making art, I can't do this with my life.” Then I found MCAD [Minneapolis College of Art and Design], and I started getting into painting. That reminded me what it was about art that I loved, which was being hands-on and tactile with different materials.

There is something elemental or alchemical in your use of materials like fire, soil, and bodily fluids. Can you tell me about the framework of transformation in your work?

For a long time I was focused on how separate I felt from everything and how divided we all are. I just saw all these divisions and I was very focused on how people separate themselves through language [and through the way we live in cities]—the fact that I'm living in a box next to another box, next to another box—you know, how we don't see the physical earth. We've separated ourselves in so many ways—physically, figuratively. I eventually got to a point where I realized that it wasn’t good for me, mentally, to keep thinking about all the bad and how I'm not connected to other people. So I started thinking, “How do I flip the script and start noticing the ways in which I am connected to everyone and everything?”

I think part of that is my transness and coming to understand my connection to other people, to the land, and even to my family. For a very long time, I didn't feel connected to my family at all. I think understanding myself as trans is when I started to find my place and connection to other people in the world; things just made so much more sense. My trans identity doesn't just exist in this gender way.

Growing up as first-generation Mexican Norwegian Americans, my sister and I were pretty ethnically ambiguous. We would get questions all the time from kids, like, “Are you this or are you that?” Basically telling us we have to choose, as though being Norwegian meant I couldn’t also be Mexican. But my mom was always like, “Oh, don't pay attention to that, you're a child of the world.” I didn't really understand it at that time. But now, that makes so much more sense because I understand that we are all actually connected, that the earth was once one land mass. The land itself doesn't have a border between the US and Mexico.

I've come to this place of understanding that a lot of the lens through which I understand the world is a very trans lens. There's transness and queerness throughout nature. Things are always moving and are always in transition because we are bodies on this earth; there's constant movement, even underneath our feet. Even though I'm sitting still right now, the earth is on a tilt, on an axis, and spinning very slowly.

Fond du Lac (2024), charcoal, limestone sediment, water, wood burning, smoke, soot, fire, and resin from burning palo de ocote on wood panel. 72”x 48”

Al Quds Day Protest (Iran), 2024 | Controlled Burn Series

.jpg)

Al Quds Day Protest (Iran), 2024 (detail)

How does this approach affect your physical or spiritual relationship to materials?

When I think about the materials and forms that I'm really drawn to—[for instance,] I’ll look at a tree and I'll think, “Wow, I could never make a sculpture that looks as beautiful as that,” you know? Nature's already doing it. When I work with these natural materials like bones, wood, and hair, I am thinking about it as a collaboration with nature. Nature has already made these things and gifted them to me, in a way, or gifted them to all of us. I can't ignore the life that the material has already lived. When I think of wood—maybe I have a sheet of plywood that I'm making work on, like the paintings and drawings in [The Earth is a Body in Transition,] for example—that wood has gone through so many other transformations before it got to me. Then, I think, “How do I work with that and honour the original form that it was in or the place that it came from?” Especially trees, they’ve lived so much longer than me and have witnessed generations. For example, I currently live in this home and it has witnessed generations of my partner's family living here, migrating, and babies being born. Now, I have a wooden floorboard in my hand and what do I do with it? It’s a spiritual thing for me.

I understand my position on the earth now and that I am meant to be here. I've been leaning into that a lot more over the past few years. I think a lot of queer people have a very contentious relationship with religion and spirituality, specifically organized religion. I had abstained from any sort of spiritual practice, and when I started understanding myself as trans and started the process of social transitioning, I began to tap into my spirituality more. Coming to understand myself allowed me to be open to understanding more.

This interplay between the personal and the communal surfaces in your serous fluid silkscreen photo series that includes the prints Ren and Roman. How did that series come about?

I had top surgery in 2022 and was staying with a really close friend of mine, August Schultz, who had also had top surgery with the same surgeon that I had. Planning for that experience was very community-based because I don't have family in Minneapolis. I was dependent upon asking friends for help and support, and had never had any sort of major surgery before. They housed me and fed me and kept me warm, and propped up all the pillows so that I was not just laying flat all day, every day. They really took care of me in a way that I had not been cared for before. In that time period of recovery, I was so antsy to do something, to do anything other than just watch TV.

Eventually, I got to a point where I needed to make something. Every day, I was measuring my fluids, I was watching my friend strip my drains and write down this many millilitres, at this time. And I thought, “Oh, that's free material that I'll never get my hands on again. This [fluid] is something that is of this very specific moment in time of my life [and] if I don't do something with it, I'm going to kick myself later.” So, I asked my friend, “Do you have a jar or something? Put this in it.” They were so down for it. Also, [Schultz] is a screen printer. I was asking them questions about the process, like, “Do you think this could be used as ink?” And they were down to try it. So, I had some Yupo paper DoorDashed or Instacarted to me. I started painting self-portraits and text-based paintings of the things that I was thinking and feeling and seeing during this time; really documenting it, this surgery and recovery. Those paintings and prints could have never happened without community.

Through [the process of] making these screen prints, I thought about the other people in my life who were going to go through this same surgery soon and I wondered if they felt any type of way about saving their fluid. Now, I have four or five people's serous fluids in a fridge waiting to be turned into screen prints. I've extended the project into one that is very collaborative and community-based, and I’ve started making portraits of the people who have agreed to save their fluid for me. I'm working with [Schultz] to screen print their portraits now and also making work based on our conversations together. The project itself is rooted in trans mutual aid and the ways we show up for one another, care for one another, and create with each other.

I see transitioning as similar to the wisdom of the controlled burn. We're now at a place where we can realize that gender-affirming care, hormones, surgeries, and social transitioning are for the betterment of the individual; to preserve and allow that ecosystem to thrive.

In thinking about your recent show The Earth is a Body in Transition at HAIR + NAILS in Minneapolis, I keep coming back to this idea of preventative harm, particularly in relation to your series Controlled Burn. Made with soot, soil, and clay, these drawings all reference reparative experiences of something that is generally considered harmful, but that in some contexts is necessary for survival; from top surgery and its record of often cherished scars to a prescribed forest burn, prompting fresh blooms. What was compelling to you about this idea?

I was at a residency called Oak Spring Garden Foundation in Virginia. I had brought this resinous pine wood called Palo de Ocote with me. It’s a wand ritual tool that is used similarly to Palo Santo, but it's not as threatened as a species. At the residency, I was thinking a lot about how to make art with solely natural materials, or just with natural elements: fire, water, earth, air. I started collecting soil there because there was a very yellow, ochre soil and a very red soil.

I was having conversations with people in my cohort [about] a wildfire [that was happening] in Virginia while we were there. Maria Pinto is a mycologist who was in residence there with me and they were writing a book all about fire, and plants and mushrooms that thrive under those conditions. We talked about where and how fire has shown up in our lives. I started thinking about how this element is the reason why humans are here today. Fire gave us light. It gave us cooked food. It has been used as a tool for regenerating landscapes for all of time by Indigenous people on this land.

That resonated with me. I've heard a lot of rhetoric and I've had people tell me: “You’re destroying your body, this is not the way that God made you, why are you doing this to yourself? You were such a beautiful girl.” This is something that I know a lot of trans people deal with. I see transitioning as similar to the wisdom of the controlled burn. We're now at a place where we can realize that gender-affirming care, hormones, surgeries, and social transitioning are for the betterment of the individual; to preserve and allow that ecosystem to thrive.

It’s similar to the Target in Minneapolis burning down [during the 2020 Black uprisings] and everyone being like, “Oh, no, the Target.” Well, no, because the Target's not what matters, it's the people who live in that neighbourhood that matter. Through the conversation with my friend, [Pinto,] we started talking about the uprisings and about the murder of George Floyd, and everything that followed. I was living in Minneapolis during that time and I was very involved in mutual aid, including taking money from the state and giving it to George Floyd Square and to protesters—redirecting and redistributing arts funding towards that cause. In the same way that I needed to do something harmful to my body in order to really preserve myself, I think the people of Minneapolis did the same: burning down the Third Precinct or burning down the Target, making their voices heard and making it known that they have the power. They are the people who [our societal] institutions should be serving and protecting, and they're not.

There’s a telescoping that happens between the surface of your drawings and their frames, on which there’s detailed wood burning that feels more diagrammatic. Many of the frames kind of echo each other, like the keffiyeh pattern on the Al Quds Day Protest (Iran), the stitch marks of Micah, or the map on the frame of Third Precinct.

In the Third Precinct drawing, the wood burning is the map of where the Third Precinct used to be. I mean, it's still there but it's in shambles and fenced off. If you were [from] Minneapolis or if you're familiar with the area, you might recognize that that’s the actual grid of the city. So where it meets in the middle on the front is the area where the precinct would be. I wanted to bring another element to the work that is another form of a controlled burn, materially and process-wise. I wanted to play with drawing in a different way. I felt that there was an opportunity for adding a little bit more context because I think sometimes the images can become very abstracted. Like for the landscape one, the flowers that are burned into the side are flowers from that area in northern Minnesota that thrive with fire or that grow the quickest after a fire.

Some of the sculptures in The Earth is a Body in Transition have a memorial, venerative quality to them, particularly Chicago & Lake Street. What is that work constructed of and what is the significance of its name?

It’s completely made of found objects that were collected from that intersection from a burned-down building, [The Chicago Furniture Warehouse]. Unfortunately, it was a building that was an immigrant-owned business. In these moments of protests, there are always people who are not really with the movement, who are just causing chaos. This was one of those casualties, this business. I had been commissioned in 2022 by Bare Bones Theater [in partnership with Teatro del Pueblo] to collaborate with another local artist, Johanna Keller Flores, on making a public art piece to memorialize and grieve the fires on Lake Street. There were these really beautiful rubble pieces that were burned. There were parts of the building that you could just see were foundational structural points, so I went with my collaborator and picked up a bunch of these pieces. Chicago & Lake Street is completely formed out of remnants from that specific business and so it is a monument to that moment in time, that business, that intersection, and what was specifically happening in South Minneapolis.

You also have a close relationship with a specific location in Northern Norway. Can you tell me about your history with that landscape and the work you have done there?

My photo series, KROPP/BODY/CUERPO, is made in Northern Norway, in this small village of 400 people called Kjerringøy, where my grandfather was born, and his father before him. The land where my grandparents' farm is, Tverbakkan, is where my last name comes from. I have a very close relationship to this landscape. I was baptized there when I was a baby and I've gone there every year since I was born. I started making this work in 2023, in that little village.

One of the limitations of land art is solely working with the natural materials and the landscape. At that point, I had worked with natural materials before in the studio but had never made the outdoors my studio, so I started playing around with that. An artist whose work I've loved for so long is Ana Mendieta, especially her Silhuetas series. I thought about what it would look like for me to make my own silhouettes from the rocks, moss, seashells, and trees found there. So, I started working on-site in the landscape to make these silhouettes, then photographed them.

A year later, my grandmother passed away. I was already thinking about death and disintegration and returning to the land. I had gone on a walk through that landscape, and I wasn't looking for it but I came across [one of the silhouettes] falling apart and I was just so surprised that I stumbled upon it. I didn't mark where I had done these pieces. I didn’t have the intention of returning to them. I didn't think about it in that way. So, I sent myself out on this scavenger hunt looking for these silhouettes. So many of them were impossible to find since they had gone through a whole year of snow, ice, and animals grazing in the area. I photographed the few I could find.

I've always thought about that place as the one that I would return to. Even though I wasn't born there, I know that I'll die there. I know that landscape holds so much for me. After I made those first few silhouettes in 2023, I came back to the US and I was thinking, “Maybe I should try to make some of these in Minnesota.” Then I thought, “No that just doesn't feel right”; there is a site-specificity that is integral to the work... I have such a deep relationship with that specific landscape in Kjerringøy and it feels so natural to work with the materials there and to allow them to return back to the earth.

Chicago + Lake St, 2024

KROPP / GRENER, 2023 | KROPP / BODY / CUERPO Series

Your 2023 performance Equilibria evokes narratives of navigation and rebirth as related to identity. How does performance relate to your studio or land-based work?

I've never really considered myself a performance artist but I've always been super interested in process, and there is a performance in the making of a lot of the work that I do that is not necessarily seen. So I started taking these videos—they're all performance-for-video things that I've done over the past few years. Equilibria was the first performance I've ever done for a live audience. I was invited to be a Q Stages Fellow, which is [a fellowship] through this all-trans-led arts organism called Lightning Rod. I bought a literal tonne of red clay to make a landscape in the theatre. I wanted it to be immersive. I wanted it to be bigger than what I had been doing. It ended up being multilingual, [with] my voice [speaking in] different languages throughout the performance. There were bells tolling at the beginning and at the end. I contracted two violinists to play this 15-second riff from a song. As one would end the riff, the other one would pick it up and it would just go back and forth. The song—it's so funny—is an Avenged Sevenfold song.

That’s funny, I was enjoying the Linkin Park references earlier.

Yeah, it's something that I think is so funny because over the past few years, I've embraced that this is who I am and where I come from. I was a little emo kid, just sad and playing my guitar, and for some reason, I identified with older men who were depressed and had addiction issues. [The song] is called Afterlife, which is also very fitting. In the beginning of the song is this violin and this build-up, and I wanted to cut it off. So I was just using that intro. We kept it to these 15 seconds, this riff that leads up to this climax. But then when the other violinist picks it up, there's no release. You're never getting to the actual song, only the intro.

I wanted to tell this story of coming from this mound of earth, being a queer person, and not knowing what the path is, or where to go… The arc of the performance is me being born or emerging from this clay mound. The idea was to cover myself in that clay as much as possible. I wanted to literally make a monument of myself. I wanted my body to disappear behind the clay. Then I just stood still for 20 minutes and let the clay dry on my body. When I started moving back to the mound, I was making these very small movements that resulted in the clay cracking off my body. I was breaking out of this shell. From that point on, I was returning back to the mound. I was moving in a way that indicated that I was weakening or disintegrating, still also not knowing where I'm going.

It kind of works against received ideas of what coming out or rebirth looks like: as new and improved, metamorphosized versions of ourselves.

Blooming—and now everything's all great! [Laughs.] And, no, actually, it just keeps getting harder. I feel like I have to come out every two years or so with a new thing. I know a lot of queer people feel like that. There are these high expectations of me to do something or to be someone, but nobody's helping me. Nobody's telling me. My parents don't know what transitioning means, they didn't know, they never sent me to therapy. They never asked what my pronouns were…There’s so much that's just out of reach because I don't have queer elders, I don't have trans elders.

Are there any objects that act as lodestars or guides for you now?

My grandmother used to collect rocks and shells and things from that area in Northern Norway. When we were going through her house last year, my dad wanted to just throw things away and I thought, “No, that's a rock that she picked up from the ground and put in her house for a specific reason.” I have a rock collection of my own. I know where most of the distinct ones came from, but some of them are just a pretty rock I picked up. I do have a lot from Norway, some from Mexico.

I have a lot of handed-down artworks. My grandfather was a landscape painter. He made a lot of paintings of Northern Norway, where I now go and spend all my time. Those are paintings I grew up with in my house in Houston. I have some here now in Chicago, ones that I've travelled with and brought with me. There were 50-plus paintings when we were cleaning up [my grandparents’] house. [My grandfather] was self-taught and he just really loved that landscape. They’re not the most amazing paintings I've ever seen in my life, technically—but for me, they are [amazing]. I remember sitting down with my grandfather and him holding my hand and drawing with me. I remember receiving a specific painting from him. There’s a little note on the back, using my dead name probably, saying “I love you” and “can't wait to see you again.”

I hold on to all those little objects. In a way, those are guiding lights or reminders of what is important to me. Not only because of the person who made it, but the landscape that is that peninsula in Northern Norway [is] where I have the most fond memories and where I grew up getting to know my cousins. I think those are probably the most important ones. That is the landscape that I feel the most connected to, that I see myself in, that I've always felt safe in.