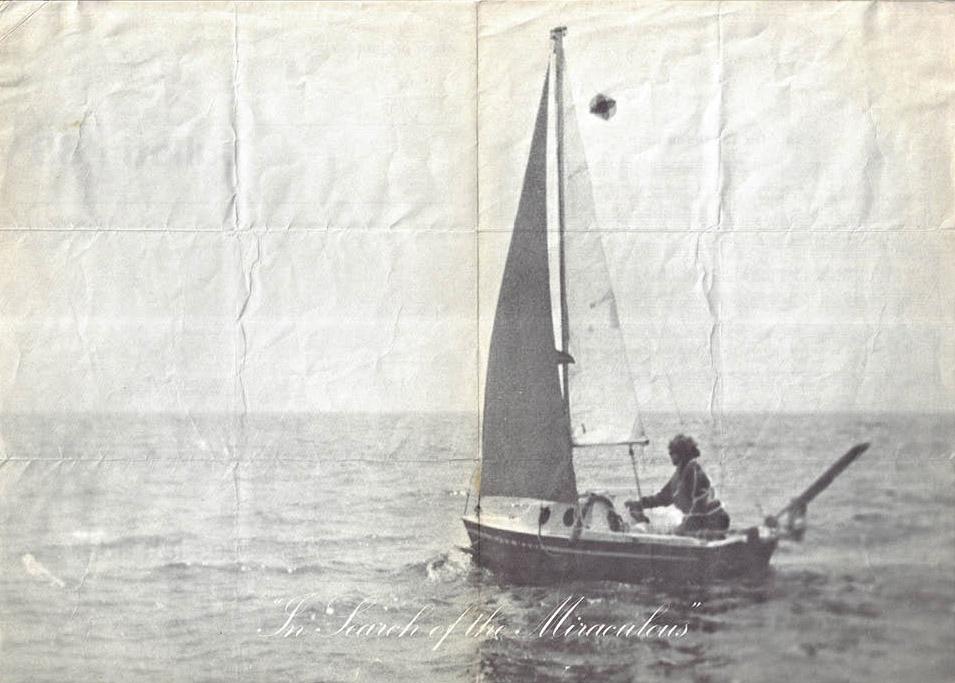

Bas Jan Ader, In Search of the Miraculous (songs for the North Atlantic), Bulletin 89, published by Art & Project, Amsterdam (1975)

There, in the night—the quiet. Where the sea feels forever and exists independently of you.

Your boat moves softly beneath you. It feels too small, and you feel too fragile against the enormous dark.

In this moment, you are not someone’s anything.

You are only the moment before the fall.

Suspended, forever. Here, again.

You, brushing the corners of distance.

Your shape at the edge of a nerve.

Nothing.

It is Nothing but the Miraculous.

——

This is the image that returns to me often. A body, a boat, the forever. A gesture toward the infinite that ends in disappearance. Long before I knew what it meant to disappear, someone else had already done it. Not metaphorically. Entirely. This was the Dutch artist, Bas Jan Ader.

On July 9th, a half-century ago this year, for the second part in the triptych of his final work, In Search of the Miraculous, Bas Jan Ader attempted a solo transatlantic voyage in a small sailboat. He vanished.

Then we turned him into myth.

——

When he left, it was from the unimpressive shores of the Atlantic—where I’m from. Where Julys feel holy and the sea pales into its own blue. I touched the Atlantic as a kid along the coast, before I knew what it meant to vanish. Before I understood how the ocean doesn’t hold, it only takes. I followed the waves like they wanted me. That was how I learned to follow what won’t stay, my first lesson in absence.

That was my beginning. Now, I live in Los Angeles, where Ader began his own kind of ending. In the first piece of his triptych, he walked the city at night. It ended at the edge of the ocean. That horizon again.

Currently I am retreating from Los Angeles to a beach town north of the city. I can hear the Pacific, interrupted only by the passenger train that could return my body back to where I left. There’s fog. The clouds feel low enough to touch. I walk toward the water before anyone else is awake, and I feel my body soften.

There’s something particular about wanting to disappear in Los Angeles. It isn’t psychological—it’s corporeal. A weight felt more than interpreted. The marine layer makes everything blur: a sky and a sea indistinguishable, like grief that has no outline. Maybe that’s why Ader began his triptych here. His silhouette floats in a familiar space—where the moon doesn’t just reflect, it appears to fall. Not symbolically, but bodily, into the Pacific.

There’s something in that. Something like surrender.

Like him, it’s not gone. Just somewhere else. Always.

But I do think about him differently now. In a world where artists are expected to constantly narrate their lives, where loss itself is content, and where even disappearance must be made legible through documentation, captions, and branded vulnerability. What does it mean to vanish on purpose, when contemporary art culture rewards presence, self-disclosure, and the aesthetics of transparency? What does it mean to choose erasure? To vanish—truly vanish—is no longer perceived as art.

This is why it endures: it’s not just about loss, but the impossibility of closure. In Ader’s hands, disappearance becomes not a lack, but a language. Which is why it feels so foreign now.

A strategy for outlasting containment. For becoming unclassifiable in a world that wants everything named. Even grief must be polished, curated, spoken aloud.

Sometimes I wonder what the sky looked like the moment I first saw someone I’d loved, or the last moment with that person, with the sky. But the sky is not a witness. It’s a placeholder for longing. A screen.

Like our digital selves, it mostly only reflects.

We chase it like we chase legacy, like pixels, aesthetics, a shape we hope to be recognized by.

Ader’s work moves against this. His final gesture denies access. It withholds.

There is no record, no footage, no definitive account. Just the space left behind and the ache of unknowing.

In a photograph from years before, Bas Jan Ader is beautiful. He is blurred–midair and already leaving us. Already becoming myth. Still-framed, holding the sublime one-tenth of a second before the world calls him back. Becoming the flicker of suspended stillness before gravity reinforces itself.

This image taught me something about grace: that it might exist only in the instant before erasure.

Mythic Disappearance

I think of the musician Jeff Buckley, who was pulled under a tugboat’s wake. Not in a delicate staged disappearance, but in a final moment music doesn’t outlast. Of Jeremey Blake walking into the surf, framing the shoreline one last time, as if image could carry what his body could not. The sea edits what it touches. It rewrites intention.

Like Ader, they were folded into the story we tell when we want the leaving to mean something.

But Ader’s work wasn’t about making meaning. It was about what resists possession. The missing piece. That’s what scars. The fracture, the blur. The body in free fall, not asking to be found.

Ader’s photographs aren’t more tragic because he vanished. They’re more miraculous because he knew he might.

The water didn’t kill him.

It carried him out of the frame.

What holds the center is that difference: being lost or going on your own terms.

The ocean doesn’t crash. It presses. It tries to take you by force. It forgets you slowly.

The horizon is not missing; it never was. It has long released the horizon. There is no edge. Just the indifference of water blurring into sky. Not darkness, exactly—but the failure of reflection. The kind of sky that gives you nothing back, not even your own outline. What it gives you back is nothing.

We don’t vanish now. We announce.

We narrate the act of leaving before we’ve gone, explaining our absence before we’re missed.

But Ader’s vanishing wasn’t about strategy—it was a gesture toward the ineffable.

Not an ending, but a thinning. The point where meaning stretches so thin it becomes air.

Today, that kind of disappearance reads almost illegible.

And yet, some artists still move toward the edge. They test how close one can come to vanishing without being lost.

To ask how little can remain, and still be felt.

Ader’s retreat doesn’t just haunt—it becomes a touchstone for how artists now contend with loss, memory, and the limits of being seen. Some artists don’t seek disappearance, but proximity to its edge. They work in soft undoings.

That’s what Wolfgang Tillmans offers at times. He doesn’t depict disappearance; he inflects it, letting the image itself begin to evaporate. Not loss, but the threat of it. Held, momentarily, on paper.

In Photocopy (Barnaby), it’s a lover under the scanner beam. His body blurs into shadow, his skin turned to grain. Still, he looks at you. That’s the part that breaks me. The gaze doesn’t vanish, even when the body does.

Similarly, Springer IV doesn’t document a dive—it records the body breaking. A pale back thrusts into black water, the image pushed to the edge of legibility. This shows what disappearance can be: slow, intimate, deliberate.

The photograph is almost bruised. You can feel the friction of repetition, the moment repeated until it forgets itself. Until the form gently crescentos like a wave going back into the dark.

The ocean isn’t even visible. It’s a grey rendering of nothing.

Christian Boltanski’s work doesn’t offer mourning. It stages vanishing as an operation.

In Les Archives, rows of metal tins and dimly lit photographs recall a forgotten archive—portraits with no names, containers that might hold ashes, buttons, hair.

The system is complete, but the identities are not.

He doesn’t treat disappearance as a metaphor. He performs it—over and over—until even the idea of remembrance feels hollow.

These aren’t tributes. They’re warnings.

You stand before them and feel not grief, but bureaucracy swallowing memory whole.

Sometimes the void isn’t my shadow against his, but a generic box.

What Ader hints at—the sublime gap—Boltanski mechanizes.

Erasure as inventory.

In Somewhere in Between the Jurisdiction of Time, David Horvitz tries to send the ocean. He bottles its water and mails it across borders. But it doesn’t make it. The bottles arrive emptied out, only salt clinging to the glass. Like the ocean, tears, Sunday mornings —it’s the aftertaste.

The act becomes its own kind of loss, another reminder that even something as vast and relentless as the ocean can still leave you behind. What’s left is never what was meant to be kept, only what refuses to cross. It's residue.

And yet, something happens in the telling. I imagine the bottle arriving empty, the slow retreat of the water, the sticky substance that’s left, a new quiet panic rising with that realization. Horvitz is not mimicking mourning—he is creating the conditions. This simple yet intimate retreat, holding space for something unable to be held.

It would be easy to make all of these artists beautiful in their leaving. To call Ader a martyr to melancholia is too easy and too comfortable. It flatters the ego of a particular kind of artist: white, male, self-authored, allowed to disappear without being forgotten. He becomes a ghost we worship instead of a myth we question. But disappearance, when only available to those already centered, isn’t transcendence.

It’s a privilege dressed as poetry.

But there are other kinds of absence—ones that don’t retreat into myth, but refuse resolution altogether.

Disappearance as Violence

Where Ader drifts into the infinite, artists like Ana Mendieta and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha confront disappearance as fracture, as violence, as intimate disintegration. I think of Mendieta’s body flung from a window, the stained wall that marks her. Her work, like in her Silueta Series was performed with blood, fire, soil and was always in conversation with absence, origin, and exile. She buries herself into the land long before she was thrown into it. Cha’s work inhabits the unsettled border between memory and loss. Her death, shortly after Dictee’s release, leaves the book holding a grief it seems to anticipate.

Additionally, Sophie Calle’s absence is performative but never clean. Her works like Take Care of Yourself and The Address Book show grief as method, as labor, as something meant to be survived rather than sanctified.

Together, their erasures are not aesthetic gestures, but contested sites where memory is unstable, grief is opaque, and the archive is unwilling to keep them.

Their contested absences expose what Ader’s myth conceals: disappearance is never neutral, and only some are allowed to vanish into poetry while others are swallowed without mercy. Disappearance fractures along uneven lines; mercy is not shared.

To vanish now is not a clean gesture but a negotiation. Ader’s absence might feel mythic, but the artists who come after complicate that myth. They don’t disappear to be remembered—they work in the unstable space between presence and undoing. Not to escape the frame, but to question who gets to occupy it. That, too, is a kind of disappearance: not poetic, not purified—but insistent, fractured, alive.

In Search of the Miraculous resists interpretation even as it invites it.

Its structure mimics faith—triptych, pilgrimage, disappearance. A night walk through Los Angeles. A transatlantic crossing. A promised return.

But there’s no reward. No final revelation. The work trails off into uncertainty. A dirge without a body.

And still, the sea waits. Not in mourning, but in muscle memory.

Now, I’m standing on the beach again. It’s night. The ocean is black and breathless.

Somewhere, inland, something is burning. I can’t see it, but I smell the smoke, drifting toward the surf, disappearing into fog.

The last time I was here, I was in love.

He stood beside me, barefoot and talking about something I wish I still remembered.

I reach into my coat pocket and pull out something dry. A flower crushed and shriveled. One he gave me.

It crumbles in my hand the moment I recognize it.

This is how they go, these sad male artists. Not with spectacle, but with the blessing of myth. Into fog. Into water. Into legend. The tide takes them, and we call it transcendence, because it’s easier than asking who was left behind. They vanish gently, while others are not permitted to disappear without consequence.

It is not a legacy, but a sensation fleeting enough to feel profound, selective enough to erase everyone else who stood beside them. Watching the tide take them back. If mercy exists, it’s in the pause before the fall, not after—before the body leaves.

Here, where the water takes what it wants, only some are carried back. The rest slip under, unseen.