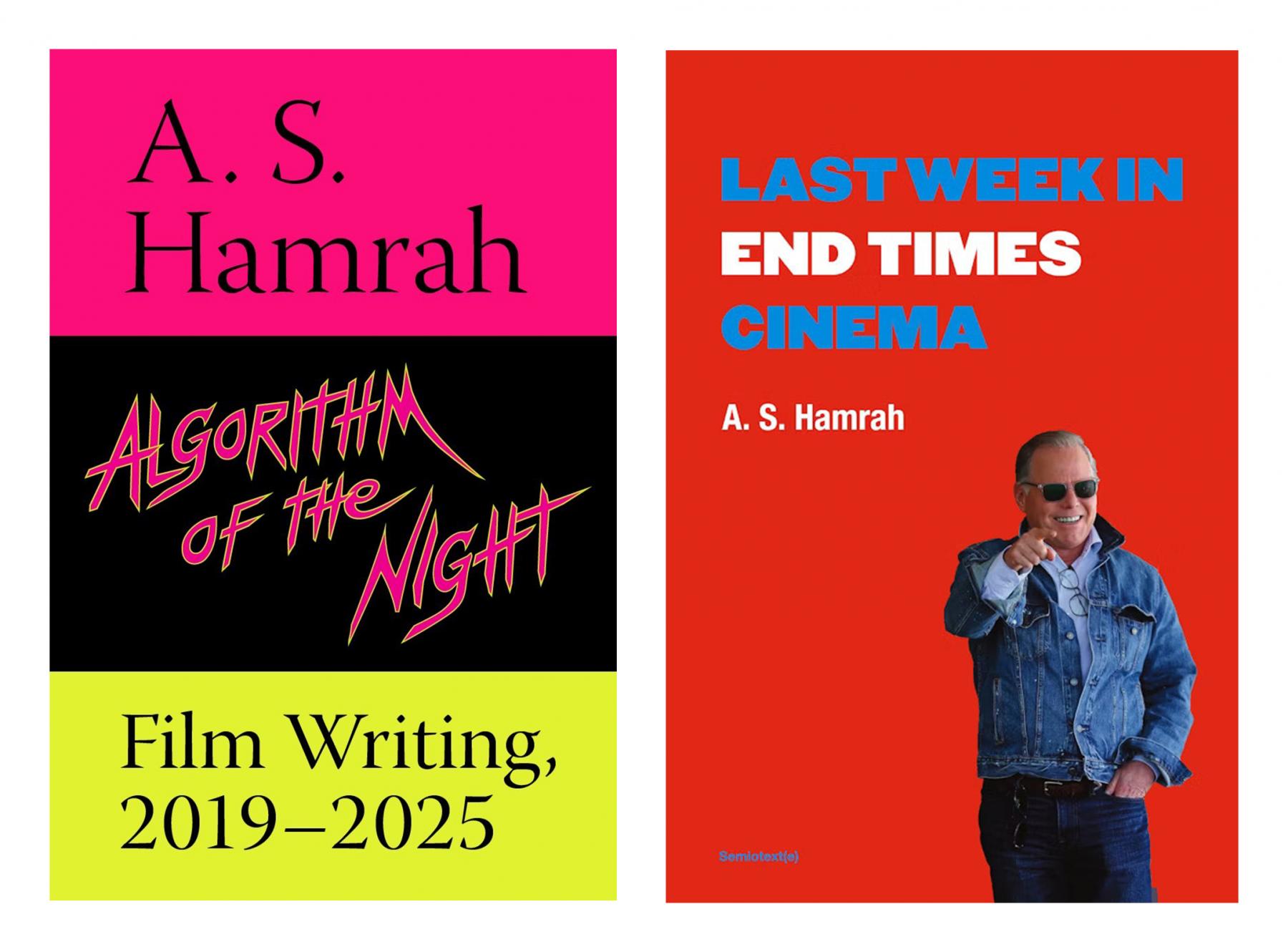

Book covers for A.S. Hamrah: Algorithm of the Night (2025), n+1, and Last Week in End Times Cinema (2025), Semiotext(e),

A few nights ago, I went to a screening of Letter to Jane, the 1972 essay film by Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin. Speaking with the audience over Zoom after the film, Gorin said, “There used to be critics.” He recalled how, in the 60s and 70s, filmmakers could actually be in dialogue with others about their work. “Today, the only critic I can think of is A.S. Hamrah.”

For several decades, the writer A.S. Hamrah has contributed to publications like n+1 and Bookforum. His criticism is laser-focused, unfazed by the soft language used all the time by corporately owned entertainment outlets. Hamrah has the unique and so-needed skill of being able to dispense with bullshit entirely. He’s frank, and very funny.

It’s great news, then, that Hamrah has two new books out. The first is Last Week in End Times Cinema, a printed version of his online newsletter, “an almanac of every bad thing that happened in the film industry from mid-March 2024 to mid-March 2025,” (Semiotexte). Formatted just like the original email publication, End Times Cinema sticks to the basics. You won’t find any essays in here—just lines of news items and Hamrah’s subsequent thoughts. The setup is somewhat similar to a joke book, although the joke is on those of us who care deeply about cinema. In a time of corporate merger after corporate merger, the rapidly increasing bubble of AI, and plain old un-originality on the part of Hollywood studios, it can be hard to find a silver lining for the future of the art form. Thankfully, that’s where Hamrah comes in. If he hasn’t got a silver lining, he’s at least got a welcome critical perspective on things.

Hamrah’s other book, Algorithm of the Night: Film Writing, 2019-2025, is the second collection of his criticism put out by n+1, the first being The Earth Dies Streaming: Film Writing, 2002-2018. That book was my introduction to the critic’s work, and Algorithm of the Night is a fantastic follow-up, consisting of capsule reviews and longer essays. This book is full of the brilliant writing that has solidified Hamrah’s status as one of the best film critics working today. I tore through the pages in mere days.

Connecting over Zoom, we spoke about both of these books, Hamrah’s memories of his former stint working as a brand analyst for television, and his thoughts on the film industry at large.

People want to go to the movies. People love movies, we understand that, and they want to go to movies, but the way that they're being exhibited now is not a recipe for the future.

In Last Week at End Times Cinema, when you write down these headlines and archive them, in a way, you begin to chart something. What stood out to you over your year of collecting these bits of news and non news?

Well, it is a kind of a charting of something, of a year in the Hollywood film industry and the film industry around the world. I did it with a certain amount of joy, a certain amount of, I guess, mirth would be the word for it. But what I noticed was that as the year went on, things became more and more dire and depressing and terrible.

There were wildfires in LA. I knew that I had to include the wildfires in LA, but I had to make sure that the tone didn't seem glib or satirical or cynical, or, you know, like I was mocking anything. In a normal entry in the book, I would probably make fun of people like Spencer Pratt and Heidi Montag, or whatever their names are. I guess those are their names. I didn't want to do that if they lost their house in a fire. I mean, it's terrible, all the people that lost their homes and all the businesses that were destroyed, and archives, museums, and people's personal collections of things.

The death of David Lynch was definitely related to the fires. Yeah, that was depressing as well. Very depressing, very sad. The fires and the death of David Lynch kind of changed the nature of it in some ways.

One of the things that hovers over the book is AI and the industry's blind embrace of it. Wasn’t there a whole strike over this?

I didn't expect there to be so much stuff about AI, and I consider anything about AI to be related to Hollywood filmmaking and filmmaking in general. So anything about AI could go into the book. I feel like when they go on strike in Hollywood, whether they're screenwriters or actors, they're still going on an old model of Hollywood labor actions, which is like the Disney animator strike—“we have funny signs.” I don't think screenwriters and actors are necessarily prepared to do real labor action. Funny signs are not going to make a difference anymore. The studio bosses have more power now than they have ever had in the history of the medium. To march around with just funny signs is to show that you don't really grasp the nature and the scale of the change that's happening.

It does seem like there are some filmmakers, some actors who are outspoken about their total contempt of AI having an actual foothold in this industry, so…

Yes, there are a lot of actors and directors and writers who have decried AI and said they would never be involved in it. However, they are not able to strike a deal with the studios on their own. They can choose not to act in something if they want to. But again, this is not the same thing as a labor action, right? I just think that it's a great time of great upheaval in the industry where they're trying to eliminate as many employees as possible and reduce the labor force as much as possible. And you know, the unions haven't really dealt with that in a significant way. They have to be prepared for real strikes, and I don't think they're prepared for that.

Is that what you think it would take to turn the tide on something like AI?

I think there has to be a prolonged real labor action that's more than just one union.

Lately, some headlines that I’ve read have made me think, Oh, this would be good for Last Week in End Times Cinema. There was one recently—a screening for Bugonia where people had to shave their heads to get in, and then at some point they stopped shaving people's heads and they were giving out bald caps. You have to feel for the last guy who shaved his head. It's like, what the hell? Then there was a screening of The Long Walk, the Stephen King thing, where people had to stay on a treadmill for the whole film. I mean, I have an idea, but what do you make of this idea that, since COVID, cinemas should be leaning more towards eventification to bring back audiences?

I mean, that's obviously not working. First of all, it works for musicals. It works for Wicked or Barbie, I don't think it's going to work for The Long Walk or Bugonia. I just found out today from two of my students that the Landmark Cinema in Pasadena now has phone chargers in the reclining seats.

Oh my God.

None of this is going to help. What helps is two things: if the movies are good and if the movie theaters are in places that are near where people live who want to see movies. So today, there's a lot of bad movies, and the movie theaters are often in dead malls where all the other stores are closed, and you go to the food court, you're the only person in the food court, and it's very weird and alienating. And Dawn of the Dead-ish.

This is not a recipe for success, and nor are films that are better seen at home. The corollary problem in Hollywood, at least—I think this applies to outside of Hollywood, to independent films too—is that they really don't know how to market movies anymore. I've always said the trailers exist to make movies look worse than they are. They've really leaned into that. I think the worst movie is better than its trailer now.

When you go to a movie, there's a solid half hour of ads, right? And something with Maria Menounos which is a complete waste of time. It's about TV shows and stuff. And then there are 15 minutes or so of trailers. If I go to see Blue Moon, I don't want to see trailers for animated children's films. If it is an R rated film, you know, it should be R rated trailers. Now it's just a melange of kiddie movies and cartoon movies, no matter what movie you're going to see.

In the newsletter, there was a story about adding ziplines to movie theaters, and another one about serving Dune-centric cocktails. I just don't think these are going to bring people into the theater. I don't think anyone cares about that. People want to go to the movies. People love movies, we understand that, and they want to go to movies, but the way that they're being exhibited now is not a recipe for the future.

It’s quite condescending.

Yeah, it's condescending, it's patronizing, it's infantile. The existence of 25 screen theaters is absurd to begin with. Now they don't have enough products to put on all those screens. So we're getting a lot of Angel Studios stuff and a lot of weird right wing documentaries, and, in certain places, Bollywood films. They just don't have enough product that they're willing to show.

Whatever film criticism used to be [...] has now been subsumed under this morass of television culture. The amount of writing about television shows is incredible now. I don't think film critics should have to write about television shows.

There's something you wrote about Barbie that was included in the Algorithm of the Night that I think could also sum up a lot of what comprised the End Times Cinema project, which is, “Barbie, like no movie before it, pushed the limit of what constitutes legitimate news versus what's free publicity for a pseudo event designed to rake in money for a large corporation.”

Yes. Barbie was a phenomenon the likes of which we hadn't seen until then. You know, I listed some of the people who were victims of Barbie-mania, who you would expect to have more critical distance from the phenomenon. They didn't, and they continued to write about Barbie over and over and over again to the point that it was nauseating and obnoxious, even under the guise that this was a good movie.

I will tell you, as someone who works in a cinema and who worked in the cinema during Barbenheimer, it was complete chaos, and it probably brought in the most money the cinema had seen in years. But as far as a person to person experience, it was hell.

There’s that woman that has that Instagram account that's just reels of her cleaning the theater after these things. Have you seen that? It's fantastic. When I was in college, and right out of college, I worked in a movie theater, selling tickets and selling at the concession stand, and cleaning the theaters. It was a five screen art house. It was never that dirty and messy. I've never seen that scale of trash. It’s like the windy scene in Challengers with the trash blowing around at night.

I mean, I'm not going to complain about people going to see those things, but the epiphenomenon becomes something that is beyond, it becomes something that the media is complicit in, in which they should know better, right? But they don't seem to anymore. They seem to think their sales are connected to shilling for these things.

Algorithm of the Night is your second collection of film writing that's been put out by n+1. How did that working relationship start? And what would you say are the benefits of working with the same editorial team over a long period of time?

I had done a zine with some other people called Hermenaut, and the guys that started n+1 used to read it. They're like, you know, half a generation younger than me. It was 2008, a weird period in my life where I kind of stopped writing. I'd been writing for some newspapers and magazines. I wrote for the Boston Globe, occasionally in some other places, online, but in general I stopped. The economic collapse happened around then, and I was looking for a full time job, and I got one doing semiotic brand analysis for the television industry. At the same time, Keith Gessen from n+1 asked me to do an Oscar column because he had noticed that coverage of the Oscars was becoming a bigger and bigger thing every year, and he thought this was odd. I told him I couldn't do it because I was too busy with my new job. But he actually did it with me over the phone. I was at 72nd Street in Manhattan, for some reason, for some work-related reason, and he basically just called me up and asked me if I’d seen the films, and then I said something about the films, and he wrote it all down. That's in my first book. That's why it's so short.

I have different editors now than I did then, different people are editing it now and publishing it now, but their whole relationship has been fantastic. And you know, it pays a little better now than it used to. They are great editors, and they'll allow me to write anything I want. Yeah, the only problem is it's not a full time job. They only have a certain amount of money in their budget. But they're great and they're very good editors. They understand me. They understand what I'm doing. Obviously, they publish these books.

That semiotics job is something you talk about in your review of Emily Nussbaum's book about reality TV, which I think is one of the strongest pieces in the book. What can you tell me about that time? How did it influence the work that you would go on to do in criticism? Did it?

Well, I had already been writing for more than 10 years by that point. I worked for a small consultancy based in New York City, in which I was kind of the number two employee after my boss, in which we were hired by television networks to provide them with cultural analysis that was oftentimes based on semiotics, but not always. In that job, I had to watch every show on television for eight years. I had to go to Los Angeles a couple of times a month and meet with the clients who were C suite level student television network executives. And not just in LA, but in other places where there were TV networks like Nashville and Miami and Atlanta.

It really gave me an insight into the television industry and how television is made. That was kind of startling to me. I had to watch so much, so much stuff. I had to watch so many reality shows. I counted it up once, and I'd seen 400 series, and it really turned me off this stuff. I kind of hate it all now, but because I saw how it was made, or what kind of decisions were made at the corporate level for it, often in terms of the branding and the marketing and the strategies of when it's put on, I began to really question people that liked it a lot.

When you're in your teens and 20s and even up to your early 30s, television has a different meaning than it does for people who are older professionals in the industry or people who just analyze the industry. I don't mean, I don't mean from a business market perspective. This is all qualitative. I just began to think that people who were really into it were, unless they were young… that these people didn't have a lot of depth. At the same time, the whole quality television phenomenon was kind of cresting, right? Breaking Bad, Mad Men, which was considered the antithesis of reality TV. But it was clear to me, while I was doing that job, that historians of the future would be more interested in reality TV than in quality drama. I think that has come to be the case. The constant celebration of things like Love Island, I find to be grotesque.

From what I can tell, there's a new episode every day. It’s essentially just surveillance.

As you know, there used to be one set of shows made in one particular year. Now we're up to season 51 or something of Survivor. Survivor has not been on for 51 years, of course, they just changed the nature of all this to make more of it. And I don't think that the audience necessarily has an endless appetite for this stuff. It's kind of going away. But when that's all they're served, that's the only thing that's on TV. It kind of changes the way people view television.

What do you think might take its place?

TikTok.

I started really freelance writing at Interview Magazine, through something I had previously done at the Wall Street Journal. They wanted me to come in for a week and they wanted to tweak the way they tag their film reviews. They were telling me they wanted to do things like, tag for ‘Films With a Strong Female Lead’ or something like that. Which makes sense if you're looking for a film on a streaming platform, but you're not necessarily searching through film coverage in a publication that way. I realized they didn't even have basic tags for their reviews. So I said, just start there. I remember when I got there, the season finale of the first or second season of Succession had aired the night before, and they were like, “We’re not running any reviews of this. That's so strange.” I thought, what do you mean it's strange? The show is about you.

The entire problem now with coverage of the movies is because arts editors at papers like the Wall Street Journal and The Times and papers all over the country and all over the world have totally lost the ability to understand what a movie is. It's just a big melange of content. I don't want to go on a rant against the term content, but there is a difference between television and movies that the streamers want to elide, and that's a problem. Whatever film criticism used to be in these places has now been subsumed under this morass of television culture. The amount of writing about television shows is incredible now. I don't think film critics should have to write about television shows. When Wesley Morris or somebody writes a whole long piece about Game of Thrones, I find it embarrassing. You've got your Pulitzer Prize winning film critic writing about how he binge-watched Game of Thrones. You know, it's mortifying to me. The New York Times’ new film critic wrote a whole piece about how she hate-binges TV shows. That's not the job of a film critic. I don't understand why The Times thinks that's a good idea to have someone doing that. Every film I go to, I want to like it, no matter what it is.

From what I could discern from the book, some of the more recent films you did like are Killers of the Flower Moon, La Chimera, The Holdovers… What are some other films more recent than that that you’ve liked?

I liked The Holdovers okay. I didn't love it, I thought it was fine for what it was. But when I wrote the short review of it, I felt that it was getting too much hate for the wrong reasons. It Was Just An Accident, I liked quite a bit. I liked Blue Moon quite a bit. I liked One Battle After Another. There's films that I haven't seen yet that I'm looking forward to seeing, like, If I Had Legs I'd Kick You. Now I live in a remote area, so I actually have to go to Canada to see a lot of movies. Now I have to cross an international border. So when I saw O Canada, the Paul Schrader movie, I had to drive to Canada to see it. I'd much rather be back home in New York City.