Leigh Bowery, Carmen Miranda, “Love Shack,” Showgirls, Björk’s swan dress at the Oscars, Macy Gray’s outfit emblazoned with the release date of her next album at the 2001 MTV VMAs, reality television, just about everything Lady Gaga has ever done—in a truly nebulous set of relations, references, and time periods, these things all have in common that they are beholden to the legacy of camp. Last year’s Met Gala put camp on our minds again, reviving Susan Sontag’s prominent essay, “Notes on Camp” (1964), and distributing it to celebrity stylists in what was itself a campy gesture of mingling pop culture and intellectualism.

Camp has not really been at the forefront of discourses surrounding cultural production over the past decade; though, in actuality, it has operated heavily in the background. We have taken it for granted as a sensibility because its cultural dominance has obscured the esoteric and sophisticated nature of camp’s history. For many people, perhaps it was “RuPaul’s Drag Race” that introduced the term and its wealth of historical references, but with no real explanation of what any of it actually meant.

The idea of standing outside of one’s larger situation to somehow observe it with complete detachment is daunting, but that is where art steps in, to act as a legible ground for complex and abstract concepts.

Season 1 of “Drag Race” came out in 2009, adopting the framework of elimination/competition reality shows like “America's Next Top Model” and “Project Runway,” complete with design and acting challenges, runways, and lip-sync battles. Today, Netflix hosts eleven seasons of the original “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” season four of “RuPaul’s Drag Race: All Stars,” and last year’s “Holi-slay” special. “Drag Race Thailand” began in 2018, and the UK series first aired last October. So, what is camp? And what happened over the last decade that catapulted an emblematic camp spectacle like drag into the mainstream, producing a global franchise and making drag queens celebrities in their own right?

During an appearance on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” following the Met Gala, RuPaul gave a pretty simple answer about what camp means to him: "It is seeing the façade of life from outside yourself, and laughing at its absurdity". As such, drag is a performative outlet that reminds people not to take things like propriety and gender roles too seriously. The dominating force of cultural liberalism, and its attendant discourses of oppression along the lines of race, gender, and sexuality, makes drag an effective vehicle for showing the material interactions of these issues. The idea of standing outside of one’s larger situation to somehow observe it with complete detachment is daunting, but that is where art steps in, to act as a legible ground for complex and abstract concepts.

Sontag’s essay remains the ur-document of the camp sensibility, which is traditionally a preserve of queer resistance, emerging from polarized times to recuperate supposed symbols of “good taste,” and reveal the notion of taste more broadly as a fictional dividing line that separates class interests. Camp glorifies character, such that an individual or object inhabits eccentricity with great intensity. The notions of Good and Bad Art—and their roots in class—are immaterial in camp, which rejects the ordinary binary of one or the other. Rather, camp offers its own set of principles for assessing art, concerned less with achieving an ideal than with revealing another truth about life and the human experience. Its aestheticism is not bound to beauty, but to stylization and artifice.

One of the most salient points Sontag makes in explaining the roots of camp in eighteenth century aristocratic esteem for romanticism, performativity, and flourish is this: “Camp taste is by its nature possible only in affluent societies, in societies or circles capable of experiencing the psychopathology of affluence.”1 Allied with the dualities of reverence and revulsion, sincerity and irony, camp’s love of opulence and extravagance acknowledges the qualities of luxury as simultaneously aspirational and absurd. Camp revels in the failure of seriousness, putting everything in quotation marks, controverting decorum as a given, and advocating style over substance. As a subversive technique of gay culture, it is a strategy of parody and self-parody, rejecting assimilation on the ground that it is reactionary. In this way, camp challenges the monopoly of high-culture and puritanism on sophistication.

Aesthetics distribute the visible and the invisible in the form of experience; something strikes just the right chord in such a way that makes us feel it has long been concealed somewhere inside of us.

Sontag ultimately hoped to clarify that camp, as a sensibility, is not a concrete idea to be furnished with a mechanized definition. She establishes some parameters in fifty-eight separate points, but notes that at its core, camp is elusive and understood mostly on an intuitive level. Jacques Rancière’s notion of “the distribution of the sensible” describes a system of “self-evident facts of sense perception” that “discloses the existence of something in common.”2 Simply put, the sensible is the innate, instinctual perception of things in the material world which unifies us, and which comes before reasoning. This is a form of sense experience and intuition, which, when extrapolated into networks of space, form, and time, determines the function of an aesthetic sensibility and its effect in the social sphere.

Aesthetics are not just about the physical objects that we see, they are also present in ideologies and relations. They are the characteristics of a sensibility that are determined through libidinal appeal (something felt to be a fundamental, instinctual component of life). Aesthetics distribute the visible and the invisible in the form of experience; something strikes just the right chord in such a way that makes us feel it has long been concealed somewhere inside of us. In this way, we can understand things like conservatism, affluence, nationalism, morality, and socialism in their aesthetic dimensions, being careful not to flatten them. Consider what speaks to you on an atomic level, as though it has been laying dormant and awakened as an imperative to your self-identification.

Jack Babuscio’s 1977 essay “Camp and the Gay Sensibility” examines camp from the film theory perspective, pinpointing its four necessary components: irony, aestheticism, theatricality, and humour. He identifies the gay sensibility as “the creative energy reflecting a consciousness that is different from the mainstream; a heightened awareness of certain human complications of feeling that spring from the fact of social oppression.”3 True camp germinated from within this awareness, which fueled its effectiveness as a subcultural practice. For Babuscio, camp is comprised of a relationship between individuals, situations, and activities encompassing a gay sensibility. He describes camp as ironic insofar as it performs contradictions between a thing and its context (in the case of drag, playing with the apparent incongruities of masculine and feminine).

The aestheticism of camp, much like irony, composes a criticism of the world as it is. These aesthetics are equally constituted by camp’s subversive nature, and this criticism occurs in three interconnected ways: through perspectives on art, life, and the practical inclinations of people and things. As such, camp’s theatricality comes likewise from the perception of life-as-theatre and the real play of role-play. Babuscio writes: “Camp, by focusing on the outward appearances of role, implies that role, and, in particular, sex roles are superficial – a matter of style.”4 The essential humour of camp circles back to its irony, which is found in identifying the contradictions between individuals and objects and their contexts, which in turn is necessarily combined with an innocence that is either sincere or invented.

Adding onto Sontag’s parameters, Babuscio establishes these standards specifically for camp as performance, elucidating a new operating method for camp to be understood in a performative, cultural matrix moving forward. Of course, what made for sufficient models in the 1960s and 70s, respectively, do not always hold up by today’s standards. More recently, Bruce LaBruce delivered the talk “Notes on Camp and Anti-Camp” in Berlin in 2012. Here, he constructed a taxonomy of camp after postmodernism that accounts for the vast and complex entangling of cultural concerns and the flattening of the aesthetic dimension to its most superficial and reactionary elements, such that the hollowest understanding of an idea comes to represent it—particularly in the political sphere. Creating categories like “Bad Gay Camp” (Will & Grace, Perez Hilton), “Good Straight Camp” (some John Cassavetes films), “Unintentional Camp” (Eyes Wide Shut) and “Low Camp” (burlesque), LaBruce manages to expand on Sontag’s treatise, adapting it for the new millennium, and accounting for the nonlinear developments in nearly all spheres of life.

LaBruce insists that, in replacing the cultural authority of irony in the 90s, camp has gone beyond a sensibility to become more of an existential condition. As such, it has all but lost its subversive power and essence of sophisticated signification. In part because of the appropriation of the gay sensibility into popular culture, and the recognition of queer communities as the new aristocrats of taste (which Sontag also mentions), the original elements have been diffused and co-opted for just about everything. Both camp and irony, then, have become so prevalent as to subdue their effectiveness as tools of critique.

In these terms, proper camp is no longer a signal shared only by a group of insiders to indicate, as Babuscio explained, an acute awareness of social oppression. The mainstream aesthetic and cultural triumphs of both camp and liberalism respectively have ultimately made conservatives the fringe actors, which we can see in the grotesque modes they have devised for performing humour and insisting on being the figures of deviance. Sarah Palin, Donald Trump, Alex Jones, and Glenn Beck all personify what LaBruce considers to be “conservative camp icons enacting a kind of reactionary burlesque on the American political stage.”5 Their rhetoric is rendered aesthetically, which is to say it is largely empty and deployed with the intent of striking the chord that resonates with certain forms of rage, pretending to have a monopoly on puritan values and morality.

In the 90s and early 2000s—the tail end of the postmodern period—a different sort of rebellious experimentation in the cultural realm became prevalent. A certain generalized feeling of disaffectedness permeated everything. Fashion of the 1990s embraced a contemporary sense of impermanence, as innovations in tech and culture fostered a more accelerated and uncertain sense of being in the world. A two-fold anxiety in the present and for the future produced an almost hysterical approach to cultural production. The aesthetics of uncertainty and instability, in a time that was theorized as the end of history but which refused to forget the past, enmeshed its images of the present and the future in a sort of multidirectional nostalgia. Grand theatricality in spectacular runway shows made fashion the arena of new performance, pioneered by John Galliano, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Alexander McQueen.

As fashion historian Caroline Evans wrote: “In all fashionable consumption, the new is overlaid on the ruin of the unfashionable.”6 The number of articles in the past couple of years on “ugly fashion” insist that this is our present condition. Miuccia Prada is heralded as the original queen of ugly, experimenting with things she overtly hated. Over the past few years, the irony of ugliness has become a staple of high-fashion through brands like Vetements, Balenciaga, and Gucci under the new direction of Alessandro Michele. Ugliness and bad taste elevated to luxury status succumb to capitalism’s demand for more experimentation, more avant-garde creations.

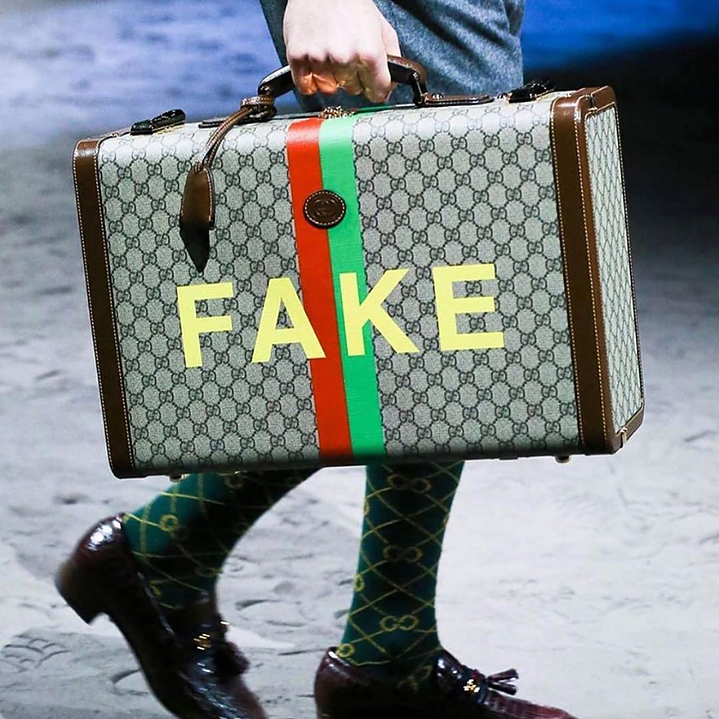

Garish patterns, post-Soviet fetishization, and normcore have attempted to cash in on the realism of ugliness, political devastation, and abjection. Designers distort proportions and promote cheap, tacky ornamentation to the level of high-fashion. Balenciaga’s platform Crocs and Triple-S sneakers are two prime examples (the Crocs sold out before they were even officially released). Some fashion houses purposely adopt the aesthetic signifiers of bootlegs and cheap knock-offs, closing a cycle in which low-quality versions of exclusive, high-priced goods now feed back into the brands that produce them. Playing into the capitalistic dilution of camp, these particular cases of bad taste with a high price tag speak to the novelty of provocation that fashion thrives on. Pushing the limits of “good taste” by intentionally injecting it with markers of tackiness and bootlegging flattens a dominant order and its attendant resistance strategies.

Appropriating motifs understood as countercultural is, paradoxically, what neutralizes their radicality. Camp is, and is meant to be, a performance and a mode of special signification between initiated groups. Employed as a marketing tool, camp is hollowed out and left to rot. It can hardly be said that campy and ugly fashion in the mainstream is still in on the joke, because there is no joke. Vivienne Westwood once said that the best way to confront British society, at the time on the precipice of embracing neoliberalism, was to be as obscene as possible. The clothes she made in the 1970s fused the transgressive impulses of both punk and gay subcultures, and a certain level of ugliness-as-vulgarity came naturally. In the 2010s, brands like Hood By Air and Vetements made this strategy commercially successful in a time of accelerated capitalism.

This is possibly one of the main reasons “Drag Race” has become so popular: it is an initiation into black queer subculture. It seemingly gives everyone permission to appropriate once-esoteric terms like shade, gag, tea, and hunty by placing them in mainstream contexts of pop culture and television. This is how aesthetics work. What originates as a reaction against the status quo is mysterious, new, and seductive to those outside. Adopting the markers of a subculture is attractive because signalling that one is in on something countercultural is itself an aesthetic choice—an aesthetic of sacred belonging. The ability to weave in and out of these aesthetics with impunity, from counterculture back to status quo, represents the power dynamics implicit in whiteness in particular. If we have learned one thing about neoliberal capitalism, it is that its modus operandi is to cannibalize all the codes, vernaculars, and symbols of transgressive gestures in order to neutralize their power. Thus any and all aesthetic choices are up for grabs—for some—and internalized individualism teaches us that we have a right to consume everything. (Think of the normalization of fetish and bondage gear worn as regular articles of clothing.)

Where do we go with our transgressive gestures from here? It is a difficult balance between protecting methods of subcultural subversion and abolishing the kinds of shame that drive people underground in the first place. We have heard it before, the capitalist ethos that deviation from the norm will be punished unless (or until) it can be exploited. The true heart of camp is an artistic gesture in the spirit of gay rebellion. Regardless of any personal opinion on RuPaul, what he has done right with “Drag Race” is to insist that we remember the forebears of camp. Camp is anachronistic, tongue in cheek, irreverent, sumptuous, political. Maybe we sat back and watched it die without knowing. Maybe the Met Gala finally killed it.