Poster by Philip Leonard Ocampo

Erotic life is a treasure we hold close until we believe its delight might multiply in the hands, eyes, ears, or mouth of another. One such place for sharing is “Erotic Awakenings,” an archive primarily containing writings hosted on the website of Toronto artist-run gallery Hearth Garage. The project is a collaboration between the gallery’s programmers Benjamin de Boer, Philip Ocampo, Rowan Lynch, and Sameen Mahboubi and writer and facilitator Fan Wu. Each piece of writing is singular in form and content, reflective of our varied erotic experiences. In an erotic moment, we might become unfastened from a solid sense of our identity, or further reminded of the body we can’t escape.

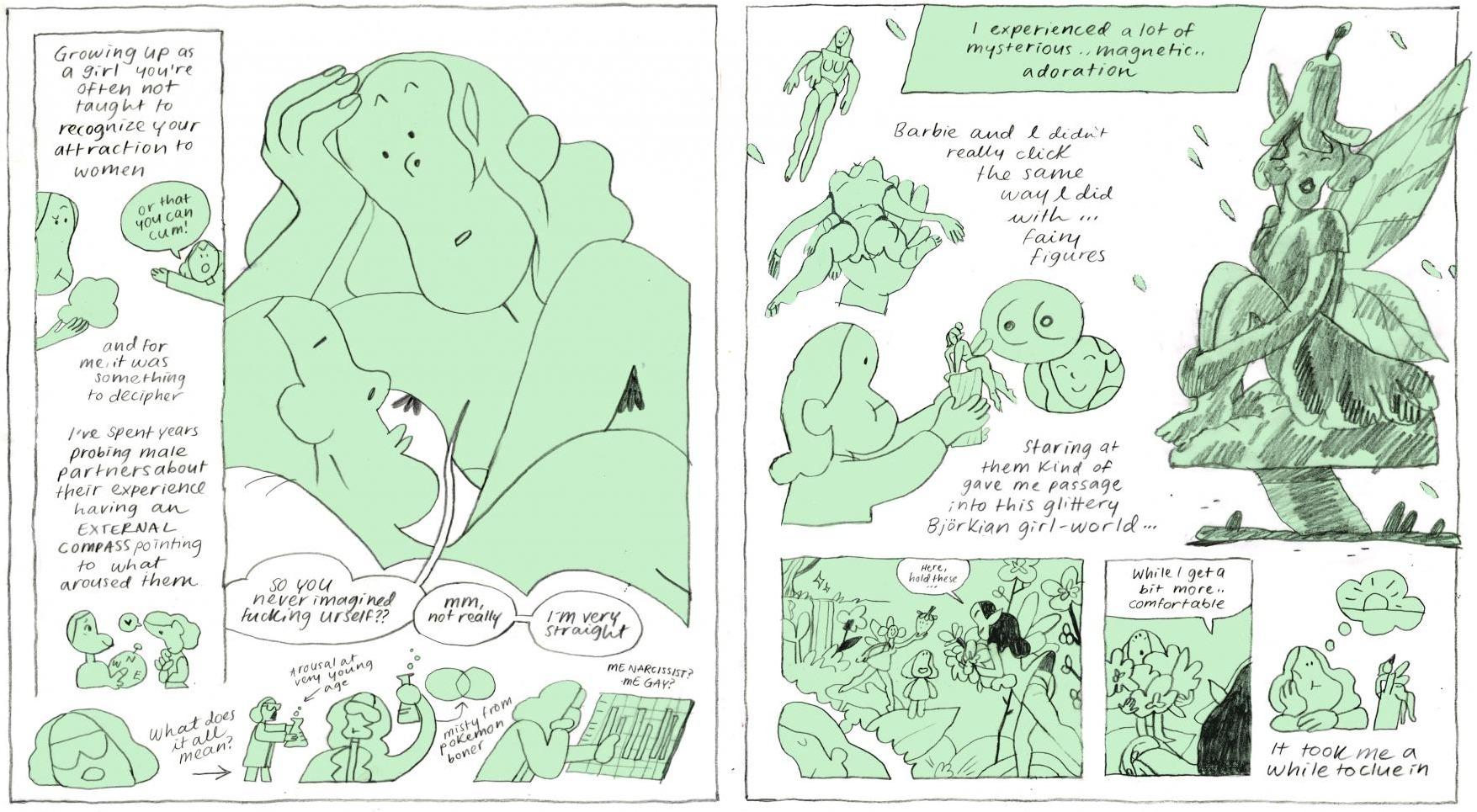

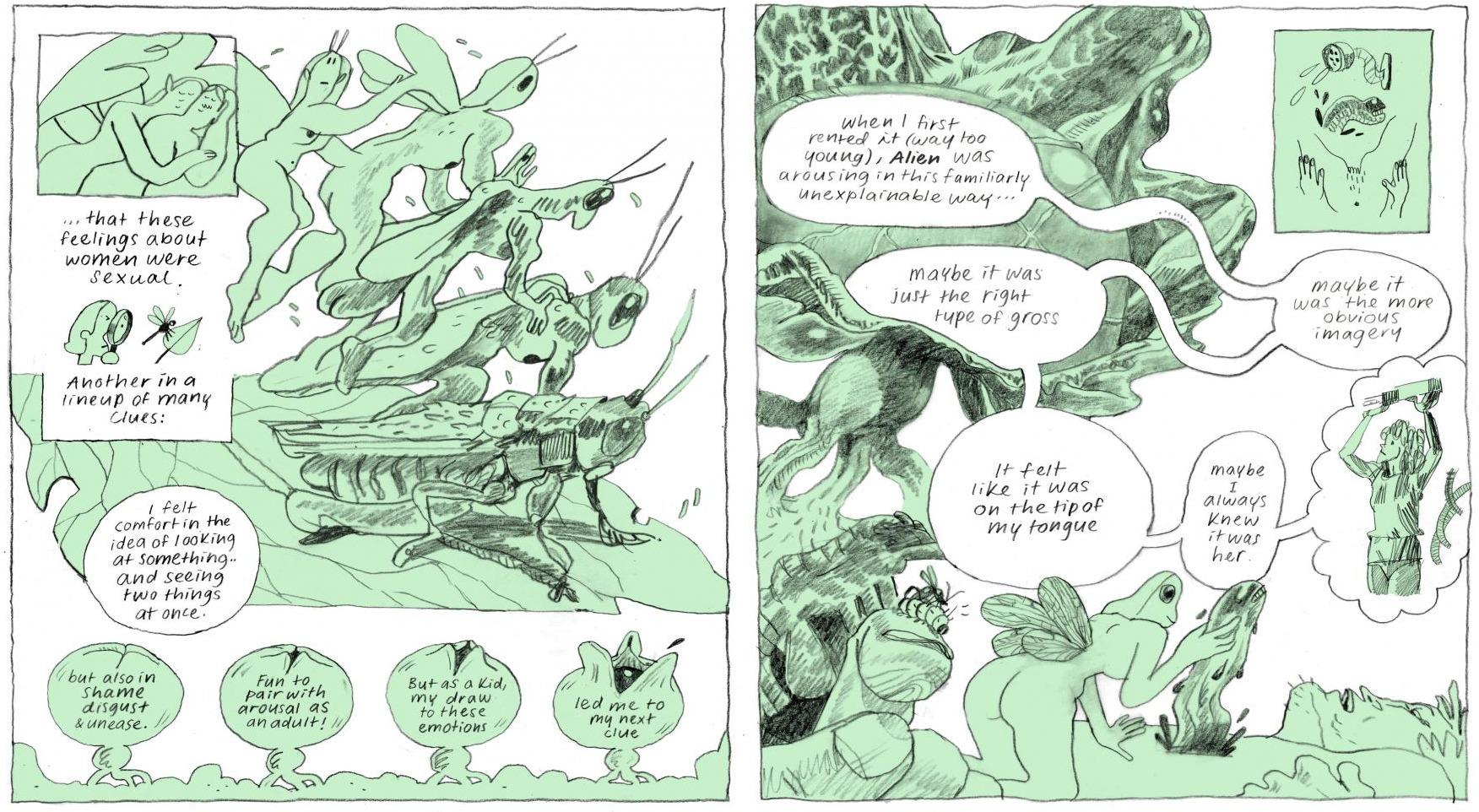

At first glance, reading the entries feels voyeuristic. In practice, however, we look out in order to look in; by watching others and the specificity of their experiences, we may catch glimpses of ourselves. In early July, Lynch, Mahboubi, and Wu met me at the gallery to speak about the collection and what the erotic might be all about.When I arrive at Hearth Garage, the door is wide open and the exhibition on view is Written in Water, a group show about memory. Wu runs to the corner store for drinks, leaving Lynch, Mahboubi, and I to chat while we wait for Wu to return. The latter are two of four programmers at Hearth Garage and part of the team responsible for reading submissions, offering edits, and publishing “Erotic Awakenings.” The project was first developed by Wu as a live reading series curated by various artists and writers. The Hearth team always hoped to work with Wu, and out of this desire for collaboration, a public archive was born. The online format allows contributors to widen their approach to storytelling. Combing through the collection, which is now in its fourth volume, you will find prose, poetry, comics, and images. Always, we witness a series of private longings on display.

Fan Wu, Sameen Mahboubi and Rowan Lynch, photograph by Maria Isabel Martinez.

Maria Isabel Martinez (MIM): How did the idea for “Erotic Awakenings” come about, and how did it find a home at Hearth?

Fan Wu (FW): It was initially a live reading project. I curated the first version of the series, and for the next two iterations, I had other people curate a set of speakers. From the get-go, I wanted the series to be very open both to contributors and curators. They spoke about all kinds of experiences, including their own artwork and its relationship to their erotic life. One person discussed the first time they had a threesome. Someone else spoke about having to wear a schoolgirl outfit and the sorts of awakenings it led to.

For me, the erotic is an energy that is dispersing all the time. It’s this difficult to pin down, inexpressible energy, that gets passed along. I didn’t feel any ownership over it. I explicitly wanted to spread it out more.

Rowan Lynch (RL): It’s nice to have a project on the go that can involve anyone. We’re casting a net and continuously inviting people to submit. [That approach] really works well for the premise, because it’s about these unique experiences, but it’s this experience that’s nearly universal. Hearing from a wide range of people is what makes it so interesting. Also, you don’t often hear casually about these sometimes-intense moments in people’s lives. As a collection, it’s inherently compelling.

MIM: I love this idea of creating an archive around something that you see as elusive, and almost trapping it. I’m curious about the title. In the program description on the Hearth website, you break it down and try to define “erotic” and “awakening,” landing at something that eludes definition and initiates a shift inside of us. Is there more you could say about those terms?

FW: I’ve been thinking a lot about identity, and the ways in which it is constructed in discourse and in artist circles—the attention that we should pay to identity, and the ways in which it simplifies things or can be reductive. The erotic was an interesting way for me to think about identity, because erotic experiences can often shatter our sense of identity. It can give us that transformational slip into another kind of feeling of our own being. I was really interested in that energy and its tension with identity—how it can mutate how one thinks of oneself, or a “self” at all.

MIM: Would you say the erotic dissolves identity?

FW: It definitely can, I feel. That’s one of the impossible relationships between the erotic and identity.

RL: I feel completely differently. I think some of the ways that I’m read in the world really influence the erotic encounters I have. If I understand eroticism apart from other people, then I see that. But I think once you’re interacting with other people, those markers come into play, and there’s almost a script in certain interactions based on how some identities are read.

FW: Yes—eroticism is inherently contradictory because there’s a political side to eroticism, but also a spiritual side, for me. So maybe the spiritual is the point at which identity dissolves. Moments of rapture, or ecstasy, or extreme devastation in the erotic are where I feel unmoored from my identity: my political identity, how my identity is read, all those signifiers.

The erotic was an interesting way for me to think about identity, because erotic experiences can often shatter our sense of identity. It can give us that transformational slip into another kind of feeling of our own being. I was really interested in that energy and its tension with identity—how it can mutate how one thinks of oneself, or a “self” at all.

MIM: Can we talk about the political side of eroticism?

RL: Some people’s bodies are politicized already, so in an erotic setting that involves their bodies, it’s hard to avoid what you carry with you. It’s touched on in different ways across different pieces. I agree that there is a spiritual, or non-physical, aspect to the erotic. I see what Fan is saying about everything dissolving in intense feeling. For our last live reading, all the pieces were shuffled, so that the person reading was not necessarily the person who wrote it. But there were some times where there were bits in the writing that pointed to who it was. You’d look around and think, “I think this person wrote this one.” Which was kind of funny.

FW: The displacement of text and body was really interesting.

MIM: Can we talk about anonymity? What is its function here?

RL: We want to give people the option [of anonymity], in case they’re talking about a certain part of their identity that isn’t public.

FW: It’s also an invitation for their full disclosure, for them to speak their story as it is with the protection of anonymity if they want it. The first version of this series was not anonymous. People were reading their own stories live. But I think because this exists as an archive online, and it’s all written down, there’s a different sensitivity to that. It’s less of an event, and more of a publication.

MIM: At the virtual launch for Volume 3, Fan described the writings as hybrids of diary entries and conventional literary forms such as essays or poems. The writings merge the public and the private domains. What happens when the boundaries between private and public spaces coalesce?

Sameen Mahboubi (SM): I think it creates an open environment. I’ve left those events feeling receptive and open. I’ve heard very intimate details and stories from people’s lives that I wouldn’t have had the privilege to hear otherwise, and that feels very special.

RL: An experience is transformed depending on how you tell it to yourself versus how you tell it to other people. That’s something we witness in the writing of these.

FW: There are new erotics to telling it to other people, an invocation of the erotic.

RL: There is definitely a voyeuristic interest in reading them.

MIM: Let’s talk about voyeurism. Here, it’s consensual, obviously. The contributors submit of their own volition, so they’re willing to be seen even if under a pseudonym. Why do you think we like to see it?

RL: I think it has to do with how their stories are relatable, but also unrelatable. People are motivated in very similar ways, but the way that motivation actually manifests is so different.

SM: Every sexual experience is so unique in such a strange way.

RL: It’s a bizarre part of life.

FW: The philosophy term would be the “Universal Singular.” [In that framework,] the erotic is considered a universal energy, which gives it this relatability between our extremely different senses of ourselves and conceptualizations of our own identity. It’s also extremely singular—the way that the universal erotic energy manifests itself in us is so highly specific. And the way we tell it is highly specific. That’s why we have this collection of comics, prose, poetry, very direct first-person writing, and more abstract writing in the third person. The forms reflect the singularity of how people feel their own experience and want to tell it.

Ripley by Sydney Madia

MIM: In your description of “Erotic Awakenings” on the website, you note: “The erotic awakening captures confusion before interpretation.” An awakening is confusing by definition; one enters into a new experience. Would you say it’s important to interpret an awakening?

FW: Some of our pieces are very analytical. They are reflecting back on that experience, trying to give language to it, adding interpretation to what was otherwise only experience. One piece called “Minor Star” weaves between the two: a description of what is happening interwoven with how she feels about those things afterwards.

RL: Putting it into writing is an act of translation. It changes how you remember things. Interpretation is something you can’t come back from once you’ve taken a memory and boxed it a certain way.

FW: The interpretation is an echo of the awakening, a secondary awakening that can be just as powerful as the first.

MIM: Sometimes the interpretation lingers a little longer than the memory.

FW: Exactly. Once you’ve come up with the language for it, you go back to the language you’ve given the experience.

MIM: You also reference a passage from Anne Carson’s essay Eros the Bittersweet: “Eros is an issue of boundaries.” That line is taken from a chapter where Carson explains how the lover comes to realize the border between the self and another, which can never fully dissolve. In that chapter, she also writes, “The presence of want awakens in him [the lover] nostalgia for wholeness.” Is desire a way to get closer to oneself?

FW: Desire tears apart the notion of the self. It makes the self really involved with the sense of the other. So what does it mean to get closer to oneself through the erotic when the self is exactly what is being challenged through erotic experience? That’s how I feel. In these erotic experiences, I lose that sense of self in other. The erotic is a sanctuary where you can explore porousness. Even if it’s not always pleasurable, it can still be an uncomfortable sanctuary.

RL: Being in a couple is often considered the standard state, which I find odd. When I think of my friends now, being single is considered a temporary state—a state between relationships, not an existence. Eroticism doesn’t inherently involve someone else. It’s a journey you can take with yourself.

SM: The erotic is about oneself in a lot of ways. It’s hard to separate myself from eroticism because I’m the one experiencing it.

FW: Do you want to answer any of these questions?

MIM: For this question about wholeness or the self: my experience of the erotic is tied to want, but also to sensation. I am initially drawn to an experience or a person because I think it will be pleasurable in some way, and this urges me to go for it. I think that that drive to pursue an experience or a thing allows me to see that desire through and learn about myself, even if it turns out to be less pleasurable than I had imagined it. So I understand both sides of what you’re all saying, in that ultimately, my experience of desire ends with me because I have to live with me, but desire takes me through the other person, or other thing.

In addition to Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet, did any other texts inform “Erotic Awakenings”?

FW: Textuality itself is almost the source of my eros. My first autoerotic experiences happened when I was eleven, sitting in my parents’ bathroom, reading erotic passages from books that weren’t erotica, but had moments of sex or people watching each other. Textuality has always come with an erotic force even independent of its content being erotic. There is something about the act of reading that really engages that sense for me. A specific text might be A Lover’s Discourse by Roland Barthes.

Text has a way of infiltrating. There are books that end up in your house that have erotic moments in them even if you’re under the control of parents who aren’t necessarily okay with letting you near these things. They don’t fish through every single book. It’s also something that’s going to come out of you at some point even if you have very little stimuli. What you have is what is around you, and books have a way of slipping into your life without people noticing.

MIM: There is a quote from A Lover’s Discourse that I love: “Language is a skin. I rub my language against the other. It is as if I had words instead of fingers, or fingers at the tip of my words. My language trembles with desire.”

FW: He gets it. That’s the foundation for having a public writing archive.

RL: Text has a way of infiltrating. There are books that end up in your house that have erotic moments in them even if you’re under the control of parents who aren’t necessarily okay with letting you near these things. They don’t fish through every single book. It’s also something that’s going to come out of you at some point even if you have very little stimuli. What you have is what is around you, and books have a way of slipping into your life without people noticing.

SM: You’re imagining everything you read. [When you read,] you’re applying your own text and subtext, it’s filtered through your own desires.

RL: One of my favourite things about the pieces [in “Erotic Awakenings”] is the intertextuality of some of them, where people are referencing specific pieces of media or books or writing. Someone wrote about Super Smash Bros and how they would look at the upskirt shots on Link. One of the pieces is on Twilight, which probably influenced a lot of people’s coming of age.

FW: At the end of that piece, one of the conversants says “Twilight ruined my sexuality.” It is a really dramatic claim—what does it mean to ruin a sexuality? Sexuality is itself a path of ruination.

MIM: What are your relationships to sexting?

SM: I find desire so pathetic. I would be so embarrassed if I ever attempted to sext. I’ll maybe send a slutty picture, and be like “Do I look okay?” The image works, and I don’t even think it’s sexy to send someone a picture of my genitals. I’d rather send a picture of a nice shirt, or if I have some glitter on and I look cute in the mirror. But when I have to write a word, that’s when everything falls apart for me. The image is so effective at conveying, “Here is what I want you to see.” But when I have to describe what I want you to feel, I just can’t do it.

FW: I write really long flirtatious emails. Sexting itself is not sexy. It’s a limited range of clichés that you can pick from.

RL: I have a hard time gauging how normal it is. I have no clue how common it is to regularly sext with a partner. I imagine there would be a big discrepancy between long distance, where people are not in contact, versus people who see each other regularly.

FW: There is also something between perversion and normalcy when we’re thinking about sexting. Maybe I think of sexting as a very “normie” thing to do.

MIM: What is “normie” about it?

FW: I think of perversion as the detours away from saying the thing itself. If sexting is all about “I’m horny for you,” or “I’m hard for you, babe,” perversion is all about not saying that, but saying everything around that. Orbiting your desires and not speaking them outright.

SM: How do we define the word “perverted” here? Is the opposite of “normie” “pervert?” That can’t be a real binary. I think milquetoast is what we’re trying to get at. I don’t know what we mean by the word “pervert” though.

FW: I don’t mean pervert like the guy who watches girls through the window. I mean it more in a psychoanalytic sense. People who are in a process of accepting how different their desire is from a mainstream inheritance of what desire “should be.”

RL: It’s such an unfixed term, too, because everybody’s definition of an acceptable form of sexuality is so different.

MIM: It is different, but I think maybe we can agree that the dominant framework is heteronormativity, missionary, reproductive sex. It is still unclear to me how the detour is more perverted.

FW: In the Barthes quote, he is talking about language as this skin of the caress, and these fingers. I think of sexting as a punch in the face. If erotic writing is this grazing, brushing against, the sext is this blunt force. Which, to me, is the opposite of the erotic.

MIM: I think of Audre Lorde’s essay “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” as well. In this text, she talks about the erotic as a reserve of power and information, and how the erotic can be accessed through an engagement with our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling. Lorde goes on to make an argument about women’s liberation, but I wonder if you agree with her conception of the erotic, and if you think the series offers a place for audiences and contributors to engage with their own erotic power?

SM: I would hope that people can come away from the stories feeling a sense of empowerment if they can relate to what they are reading, especially for disenfranchised people. I do think it’s nice to read perspectives from others who share the same race or social class as you. It’s more feedback that can be really helpful, especially if you’re still trying to find your desires. I don’t know if I can speak to the emancipatory aspect of it per se, that’s more of a conversation about from whom has desire and eroticism been withheld?

FW: The Audre Lorde question is very essential—to think about how differently desirable bodies can occupy different political positions of power. I think a lot about my journey through my own attractions to whiteness: white bodies, whiteness as a cultural fact. I’m sure that comes from my cultural upbringing, my intense desire to Westernize myself, coming out of China and trying to fit in, taking up whiteness into myself. Culture has a huge effect on who gets to own desirability in a common sense, a normal sense. Part of what we’re hoping to do a little bit in “Erotic Awakenings” is push something like—I don’t want to say the “decolonization of desire,” I don’t know if we’re that explicitly political—but offering alternative routes of desire that may not be easy to recognize when you’ve grown up with a certain set of media or culture. It’s a lifetime process.

MIM: If we think of the erotic as an affective force—something that makes us feel— then, with vaccine rollout indicating a turning point in this pandemic, what can this affective force offer us?

FW: This idea of the erotic as an existential affect is so true to me. The Greek word for Chaos is Eris, so the proximity of Chaos to Eros is really interesting too. I think it’s important that we think of sex as creation, not just reproductive creation, but non-reproductive sex as its own form of creation. It’s the creation of new channels and patterns of energy between two people that then gets dispersed into a community and even further than that. There can be horizontal forms of creation.

In terms of what the erotic affective force can offer us now, I would say the erotics of friendship. I really feel it very strongly. I already did before the pandemic, but now I feel very open to touch. I want physical contact with my friends and to let that erotic energy be expressed. And not worry so much like, “Are they going to think it’s sexual? Is this too much?” But just be in the free play of the erotics of friendship.

MIM: After over a year of not really being able to touch, even those who didn’t really feel like they needed physical touch now crave it so much more. The lack of it grew the need for it.

FW: I would love to hear more about your own conception of the erotic, and your own practice and how it involves the erotic.

MIM: I’m drawn to the erotic because I like to experience myself through the other, which is always also just an experience of the other. The erotic is how I make sense of existing. I believe that we encounter consciousness in all objects and individuals. I like to be in relationship to the world, and I think that is erotic.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

SM: If people want to submit, they should. We are sorry we can’t pay, and Hearth also receives no operational funding.

FW: But if it’s a passion for you, if you want to do it, we have a venue for you.

RL: We’re hoping to do more in-person readings in the future. Eventually we’d like to put together some physical form of writing.

MIM: What are you hoping to receive?

FW: Honesty.

SM: Have fun with it.