As we move towards reshaping the world into a reality where the most marginalized and oppressed people are able to thrive, unimpeded by state and racial violence, the mediums in which identity manifests are a moving target. Racial and ethnic categories continue to shift, dodge, and take on new forms simultaneous to the expanding social consciousness of systemic racism’s histories. Whiteness in particular continues to evade blame and repercussion for the historical, structural oppression and volatility it has and continues to systematize. Instead, we have witnessed performative allyship from individuals and institutions of power that is as ineffectual as it is performative, undergirded by the circulation of empty rhetoric for change that doesn’t attempt to dismantle the foundations of violent systems. The project of abolition is further troubled by the current Covid-19 pandemic as so much of our knowledge sharing becomes disembodied and mediated by the screen. Much of movement building and anti-oppression work happens with community in real time and is a bodily process of unlearning. Our families, mentors, and friends teach us through action. We learn about resistance and alternative world-building through a proximate osmosis, one that mimics the complicated making of communities. From strained grassroots efforts to spread knowledge, to highly-crafted political rhetoric and images, the problematic limitations of algorithmic mediation have become pressingly clear and can only take us so far.

Interdisciplinary artist Mev Luna (b. Houston, Texas, 1988) uses their work to tackle this complex intersection of race, ethnicity, state violence, epistemology, and digital mediation. Their practice traces how oppressive systems—abstract and material—obsessively surveil and shapeshift while pulling people through their trappings. This is a time when political positions are increasingly divisive, access to factual information is slippery, and mainstream media fixates on images of violence rather than visions for manifesting a new world. Luna’s work interrogates these imposed limits on how images and knowledge are transmitted, illuminating suppressed familial and kinship pathways to critique, healing, and transformation. By engaging performance, sculpture, and video, they negotiate autobiography, storytelling, and affective inquiry to realize the infinite potentials for images to change what and how we see.

If we are to understand that the U.S. is part of the Americas—while being committed to the dissolution of borders—then I must accept that colorism's impact within Latinidad applies to the U.S. context as well.

In your practice, you move between the politics of identity (particularly the unconscious pervasion of whiteness), family lineage and history, and collective memory associated with various places. Your work is heavily grounded in a very specific approach to autobiography, one that you’ve carefully crafted. Can you speak about why you leverage your family’s history to talk about these issues?

It’s a methodology that I developed, in part, to account for two occurences I see within Western artistic discourse and historical methods of subject exploration and meaning-making. The first being the way in which research-based practices–or any practice within a field for that matter– when the subject is outside of oneself/their immediate community—can lean towards the pitfalls of anthropology and ethnography, creating an “other” which we know is marred with deep and devastating consequences that range from colonialism to microaggression. And the second being the limits of identity politics, specifically within a shifting global landscape.

My use of autobiography is an effort to counteract this lean, an axis/point of pressure to exert on those tendencies–and within myself–through a personal relationship to the subject matter. There is oftentimes an acute and highly charged relationship between myself and my family members, in which shared pain or trauma holds me accountable to those subjects during my curiosity to know or represent an aspect of them within the content of my work.

It makes so much sense to hear you say this about shared pain and trauma, and how that sharing shapes accountability. One aspect of autobiographical artistic practices that I find so compelling is how by looking inwards, artists are actually complicating authorship. Their work is not a selfish endeavor about “me, me, me,” but instead calls upon and relies on the many meaningful people in their lives. Making work that readily approaches selfhood weaves a web of intimate relationships and experiences that have as much to do with others, as they do ourselves. I think a kind of collective authorship is actually generated through this process.

Yes exactly, I agree with you on the idea of collective authorship. For me, I think about the ability for grief – shared grief – to be a mobilizing force within peoples’ lives because of the profound embodied experience that it is. So many important movements have emerged from the channeling of collective grief – which extends from the loss of people to other forms of estrangement, loss, and state violence. I’m thinking here of Black Lives Matter, Indigenous land organizing, and activism in response to the AIDS crisis.

By witnessing grief as a way that has led to these forms of outward mobilization, affinity building, and solidarity organizing, I’ve been interested to see if grief could also be a form of inward mobilization. That’s the accountability part. I see outward and inward mobilization as imperative and deeply connected. Grief, estrangement, and loss guide my research – I follow those embodied experiences to where they lead me to enter my work.

Fact Checking My Father, 2017 Lecture-performance, 2017. Presented at SFMOMA as part of the UC Berkeley / Stanford University Symposium–Not at Home: Migration, Pilgrimage and Displacement in Art, Design, and Visual Culture.

Thinking of grief as a mobilizing force is really powerful, and definitely resonates with political histories and intersectional activist lineages, particularly where artists bridge the two. These affective dimensions to your work are whetted by different tonalities—sometimes taking on the coldness of analytical research and at other times the softness of intimate, personal investigation.

I like these terms “soft” and “cold” because they are inflected within my practice in different ways in various works. In my lecture-performance, Fact Checking My Father (2017), I think of the piece as having 3 selves present; the role of the artist as researcher, the archetype of the “loving child” ; and the body which performs an affective score and holds space for an emotional composition.

The set up for the performance involves two projections on opposite walls. One projection shows clips of archival footage and the other is a document projector connected to real-time magnification of the materials on the surface of a table. The researcher performs a distant, intellectual, and academic approach to the subject matter – this would be the cold aspect. The loving child I speak of, is my younger self at age 23 interviewing my terminally ill father for personal purposes, never fully anticipating that it will be activated for an artwork. Then my body in real time performs an affective score, which I wrote into the piece with as much weight as the actual script. Both the loving child and the body are the softness.

The piece needs all three selves in order to achieve the intention of the work, which is to impart to the audience, through both empirical evidence as well as modes of non-knowledge, the depth of systemic oppression. The piece also challenges how we understand truth when reflecting on past events. Too much softness within the piece, and the work could easily become sentimental, acutely situated only within the context of my personal relationship to my father and the profound loss that was his death. Too cold, and the performance is in danger of emphasizing the analytical, the vernacular of the state, which can oftentimes circumvent the embodied impact and lived experience, and therefore not be fully understood.

How has your methodology evolved over the years? I’m really interested in how an autobiographical approach deepens, widens, or becomes higher pitched. Such a practice can hold a longer note, depending on what aspect of a life is being tapped. I’m also curious about how your tactical research methods shift as different bodies of work progress.

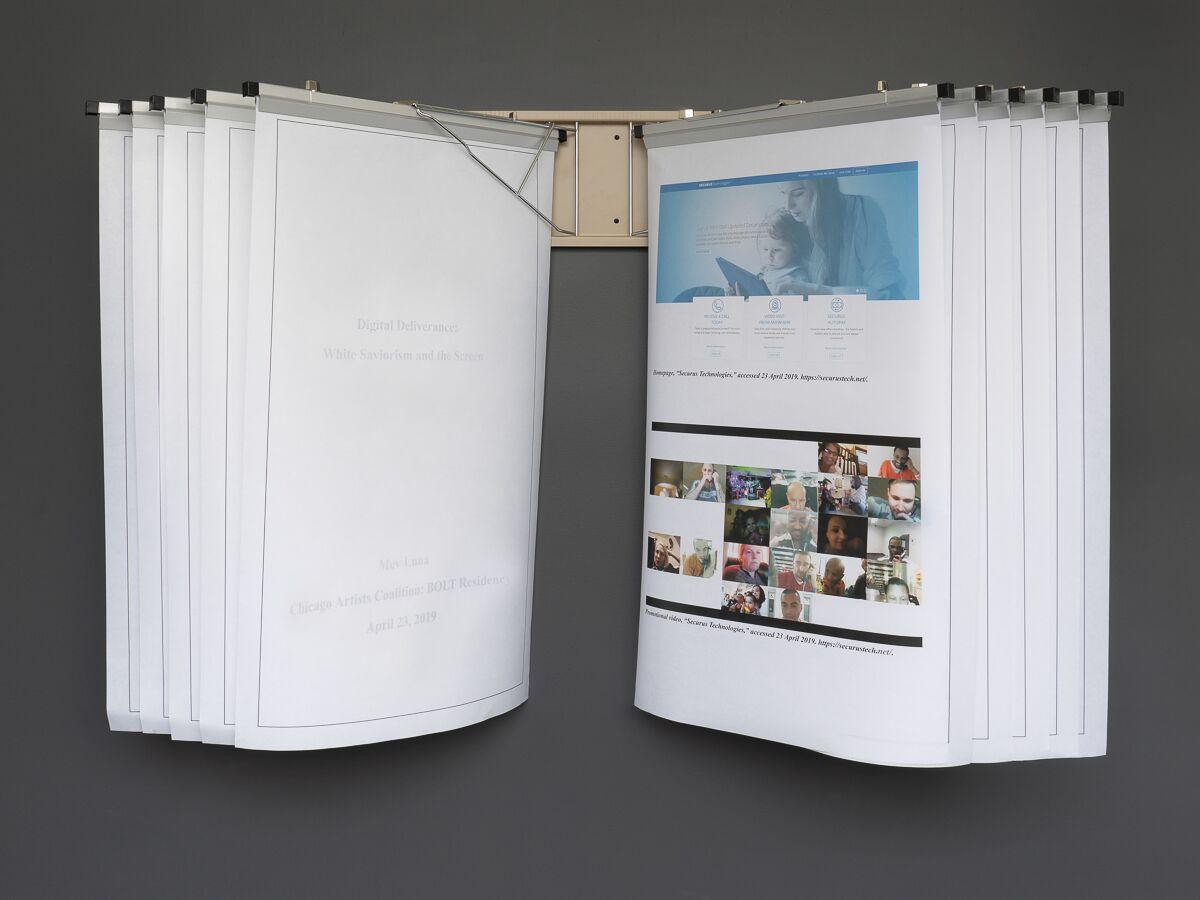

Absolutely, autobiography in my practice has acted as a guide for my work and an access point to broader socio-political issues. I’ve noticed that as I gain more time working from this approach, the pitch of certain projects has moved away from a direct connection to autobiography while still being heavily influenced by lived experience. For example, there is a history of incarceration in my family which has led to a disconnection between the generations, and various manifestations of estrangement within the overarching family structure. This has led me to consider incarceration and its intergenerational impact. My father worked the fields in a sequential progression; first as the child of migrant workers and sharecroppers, and then again as a prison labourer. As part of the next generation removed, I am very much invested in the contemporary experience of incarceration and how this relates to my work as a new media artist, namely thinking about screen-based practices, simulation, and the implications of technology and surveillance of/on bodies. My experimental essay, Digital Deliverance: White Saviorism and the Screen (2019-ongoing), critically looks into the enthusiasm of the private sector to mediate human-to-human contact within correctional, immigration, and healthcare systems. This piece, which has its first iteration as an art object, was inspired in part by the writing of Jackie Wang in her book Carceral Capitalism which delves into algorithmic and predatory policing, the mortgage crisis, and how these systems have seeped into juvenile detention. A must read when thinking through contemporary abolitionist practices.

I say that it has moved away from autobiography, but ironically enough, given the current Covid-19 pandemic and that I am a college professor who has moved to online teaching, I think the project will extend to include virtual education practices.

Digital Deliverance: White Saviorism and the Screen. Large format experimental publication, architectural blue print hanger, 2' x 44," 2019. Photo documentation: Jesse Meredith.

Speaking of how autobiographical inquiry informs your practice, I’m also curious to know how your continuous mining and interrogation of your family’s history has affected how you frame your own identity. Outside of this interview we’ve talked at length about how our identities are moving—responsive and living frameworks to understand how we move through the world. I’m thinking specifically of how complex and nuanced your experience of race and ethnicity is, and your orientation to whiteness, Latinidad, and Indigeneity. How has your work affected your life in this regard?

There have been some deep shifts in my own critical thinking, informed by my research, lived experience, and this political moment – namely that from now on it's important that I no longer identify as POC or “brown” and instead identify as white Latinx/Chicanx. I made the move a few years ago to identify as multi-ethnic, rather than “mixed race” (I have a white parent) as I had growing up.

My research led me to an understanding of the formulation of Latinx within the U.S. as a racialized ethnicity, not a race. My affiliation with brownness came from being raised within the Chicanx community in Texas, a political movement and later a set of cultural affiliations rising out of an estrangement from the “motherland” (Mexico) via immigration, and a simultaneous othering from U.S. society. It also related to how the U.S. at the time understood whiteness as being not Black and not Mexican. The plurality of this otherness, alongside deep ties to nationalism and the inheritance of the Mexican Nationalist project e.g. “La Raza”1 as a rallying chant, and in particular the Mexican proliferation of the mestizaje/metiza narrative, solidified a definition of brownness as encompassing all Latinx folks, even white Latinx, in the U.S. In conjunction, White America’s xenophobia and racism held this in place through state violence, stereotyping, and forced assimilation –thinking here of the control of language. From 1909 to 1965, Spanish, for example, was not allowed in schools in the state of Texas and in some cases there even existed segregated cemeteries for Latinx people. This formation was also necessitated by the conflation in the U.S. of all Latinx people being thought of as “Mexican,” when in fact that is not the case. Latinxs immigrate to the States from all parts of the Latin America, as well as through the U.S. colonization of Puerto Rico.

There was a historical moment in which Latinx people who would be thought of as white within Latinidad were racialized because of xenophobia and experienced the weight of systemic racism in the U.S. and I don’t want to erase that from a collective past, as the repercussions are deeply felt and many people within this category still face forms of disenfranchisement and discrimination. At the same time, if we are to understand that the U.S. is part of the Americas—while being committed to the dissolution of borders—then I must accept that colorism's impact within Latinidad applies to the U.S. context as well. There are brown and Indigenous Latinx people in the U.S., even within my own family, I am just not one of them. Thus I am white Latinx/Chicanx, Latinx an inflection of my whiteness not the other way around. I’m also an U.S. Citizen and therefore documented.

Admittedly, I held the notion that a resistance to identifying with whiteness, was a resistance to assimilation and thereby a resistance to the expansion of whiteness, when white supremacy was under threat. But it has become clear to me that such identifications do not support the fight for Black, Black-Indigenous, Indigenous, Afro-Latinx Liberation. The logic of brownness in the U.S. as encompassing white Latinxs has tethered the plight of Latinxs to the “one-drop rule”2 within the history of slavery of Black people, essentially collapsing race with ethnicity and conflating the experiences of Latinx people with those of African-Americans. These histories are not the same, and it’s necessary in our efforts to unlearn and challenge Anti-Blackness to parse out and untether this logic.

I am slow to this arrival and I am indebted to the work of my community: Afro-Latinx, Black and brown mentors, colleagues, and friends who’ve held it down while generously allowing room for my process. I also attribute this learning to my fellow Chicanx / white Latinx folks who are doing this work too, in both private and public ways. I do not want to be prescriptive to others, and especially want to hold nuance for light-skinned POC from other origins and diasporas whose colonial history is varied from Latin America.

Far From The Distance We See, video, 2019. Duration: 8:18, cinematography: Mev Luna, Eloise Santa Maria, Robert Chase Heishman, sound mixing: Julian FlavinCaption

Your work is extremely interdisciplinary, and yet you seem to come back to specific mediums often—performance and video. Why these approaches?

I gravitate to working in the form of video essay because it allows for the use of simulation, sound, and moving image which brings the viewer through an experience over a set (or looping) amount of time. I am very much interested in the idea of rendering as both a concept and a medium-specific process. In video and simulation software, rendering happens after the editing process, as a pass over the content. This process allows for others to view the contents of the edit. It is essentially what makes possible the translation of the inner workings of video viable for an audience to view.

But a rendering is still not the thing itself - it is a version that has been pushed through a system. To render means to melt something down to its essence, to cause to be or become, and to yield. I think about our experience as subjects in a similar way. We are all pushed through specific systems—which are ever-shifting. Some identifications are more malleable than others, specifically in terms of how visible or obfuscated the attached signifiers may be. The ability to be rendered in a way that is closest in form to one’s Self, some would say to be able to be rendered legible, is directly related to society and structural oppression. The depth, likeness, and complexity of how this rendering is able to take shape is correlated to one’s capacity to create and recreate the conditions of a liveable life.

Rendering can also be a capacity with which to see. In this way, rendering is related to the potentiality of images – and by extension, the potentiality of our imaginary. With all of the online streaming happening as a result of Covid-19 across mainstream platforms, I’ve been thinking about when we will, as viewers, exhaust the content of a pre-Covid world - content that for all intents and purposes draws on a particular collective imagination and capacity range. Even through speculation we could say that this range of media is limited to what was available prior to this global shift. Assuming that no new film productions can take place at this time - all of the rendering part of post-production is limited to the amount of footage captured prior to this global shift in daily life. If we were to add up all of those hours of pre-pandemic content those would constitute a particular imagination (i.e. shows that replicate life prior to social distancing and isolation, and death (slow death included here)). Even if we consider the full spectrum of representation within all the categories of mainstream TV—excluding the quick adaptation of pandemic references in advertisements–we haven’t seen a content shift that reflects how we are now living, because at least through the production aspects of film/TV it cannot be readily produced during this time.

So then I ask myself, can our imaginary be limited by what has and has not been rendered? And what is still sitting on hard drives and servers available to be rendered? Would we need to exhaust viewership of all of the rendering of images up until this point in order to access rendering’s capacity to yield something new?

Grief, estrangement, and loss guide my research – I follow those embodied experiences to where they lead me to enter my work.

And how about performance? I’ve noticed your recent work does not utilize performance as much in terms of having a ‘live’ component in your installations. Are you moving away from this medium?

You know, this is something that has struck me as well because I do have these moments in which I step back and try to look at my practice and see what is there now versus what I may think is there or what was there. This is an inquiry I’ve been asking myself, where is performance used in my work now? I’ve concluded that for the time being my relationship with performance is a methodological one. I’ve been thinking about the architecture of an installation in relationship to the body of the viewer—a performative negotiation, if you will. Looking at the original cubicle design by Robert Propst—which was meant to create more dynamic and modular workspaces, not the confining ones that we identify the cubicle with today—the series Action Office Was Meant to Be About Movement (2019-ongoing), is about the question in performance concerning viewership and audience. Working with a privacy film that renders monitors opaque at specific angles, I’ve started this series of partitions that ask the viewer to reorient themselves in order to access the content on the screen. Working with this material challenges the viewers’ access to the moving image. I think of these architectural spaces as a training ground for dealing with agency and lack of access.

Our relationship to screens, generally speaking, is that we have immediate access to content, we are meant to be able to quickly consume whatever is on the screen. Returning to the idea of the “other” or communities outside of oneself, these works are concerned with this question of who should be able to have access to whom and whose image? How readily available should images be? As I’ve found is often the case with the use of the privacy screen, viewers initially think that the monitor is turned off or not functioning properly and pause when approaching the installation. That pause is crucial, because in that moment the viewer has to reorient their bodies in order to gain access to the content on the screen. My hope is that this may directly relate to how one might need to first consider where they are from a subject place and do the work before gaining access to the “other”.

.jpg)

Installation view (and detail) of Far from the distance we see (2019) in Empathy Fatigue at Andrew Rafacz

I want to talk about the intricacies of some of your projects. You mentioned earlier some of the decisions that went into Fact Checking My Father. It’s a performance that combines archival government materials and video interviews with your late father. What’s so striking, piercing even about this work, is how neither the personal or the official are represented as fully reliable sources.

This is connected to the idea of rendering a person viable (or not) that I mentioned before and is linked to our subject positions. One way a person can be rendered viable is through state documents that constitute a person within the framework of society, i.e. citizenship paperwork, birth and death certificates, identification documents, driver’s licenses, vehicle registrations, arrest records, civil lawsuits, divorce and child custody decrees. This is a form of representation via “legitimized” norms of society. You can trace them, they are rendered, and they are legible to the state.

Then, there are the stories we tell, those memories we choose to highlight that are intrinsically subjective but nonetheless reveal our priorities. Neither of these fully constitute one’s being, the same way that presenting an image of someone digitally does not fully capture or share that person. If there is a Self, it is mediated through both the state and the stories we tell ourselves and others. Yet “we” are constituted by so much more, all of the aspects that exist in between these renderings of personhood. I wanted the performance to capture that. Ultimately, it’s my belief that nothing can stand in for human presence, and that the state shouldn’t dictate or mandate our own livability.

The soft and cold approaches you mentioned earlier activate these aspects as well. There are moments in the piece in which I intentionally withhold a “performed grief”. This renders certain moments private, despite the researcher alluding to them. For example, roughly the format of the lecture-performance is that I show a clip, reveal a fact, and then bring up state documents or other primary sources that either support or contradict the statement. Towards the end of the performance however, I share a still image taken from a video clip of my father a few months after the initial recording. He has deteriorated rapidly and I share with the audience this context and explain that this is the last bit of data I have of my father before he passed away. It is a single clip, a mere 2 minutes, 106KB of him singing to me All My Love Belongs To You by Little Willie John. This is a very intimate moment, one that would easily arouse a “performance of grief” akin to me crying in front of the audience. Instead of playing the clip, I switch the visual to one that revisits an earlier gesture my father made while telling a story related to assimilation into his white rural single room school in the 1950’s. This is part of the affective score that redirects the anticipated performance of an intimate, one-to-one grief, to a broader social political issue. I go to the document projector, bring out a bowl of water and soap, and reenact embodied aspects of his story. I undergo the motions of washing my hands, and then walking to the projection, join him beneath his digital image, same gesture different generation.

From being close to your work over the years, and even having the privilege of working together on a few projects, I know that loss and displacement are ongoing lenses through which you orchestrate research into an artwork. Your recent video installation Far from the distance we see engages these two affective axes quite directly to look at the complex, embodied crossover of capitalism and incarceration.

Far from the distance we see is quite literally presented as an axis, with the viewer navigating an enclosed space generated from a set of partitions forming an X. The angles forming the shape are not right angles, but rather a composite of obtuse and acute angles. I wanted to imply they are in motion. I suppose that’s apt for thinking about Capitalism and incarceration, both are constantly in motion – intrinsically linked. They both fracture, wreak havoc, and confine. Incarceration leads to a deep sense of emotional and physical estrangement.

The video component is edited in a fleeting manner to reflect this fracturing, as soon as one thought is picked up it moves on to the next. There is a dialectical situation I set up between separate recordings of my late father and late tío (uncle) whose lives are demonstrative of these axes–my father having been incarcerated and my tío having worked at a hat factory most of his life. Through fragments of these oral histories and snippets of my visits to relevant sites, the viewer experiences a journey through these bits and pieces. Overall the edit is recursive; it begins with the story my father told me about how when he was younger his father would light a match as they rode through the country roads via cart and donkey at night so as to act like a headlight, and it ends with a few breaths worth of myself walking in the rain holding up a match against the current of cars on Cicero Ave.

This notion of fracturing seems to stand out as important to our present moment. I think fracturing is often loaded with a negative valence, but a breaking point can also be transformative. With the pandemic still widespread and the uprisings for racial equity across the nation still going strong, we’re seeing how the strategies that you weave into your work—naming the volatile effects of capitalism and incarceration, mobilizing grief into action, reorienting viewership and social consciousness to prioritize Black and Brown subjectivities—can produce real, material change when employed at large collective scales. There is always the timely question of where art and politics intersect, and right now the query feels incredibly potent.

I think this is a moment to spend less time labouring in service of institutions while also holding them accountable, and relinquishing the individual for the collective through a focus on mutual aid, direct action, personal and structural reparations, and wealth and land redistribution. What does this even mean for “a practice” yah know? Because even the methodology I shared earlier and that we spent significant time in this interview unpacking is challenged by the discourses of the moment. I am open to this process of re-examining that we are all being tasked with. I feel less attached to my Art Practice as I once knew it because there is deep, pressing, and immediate internal and external work to be done.