At what Spatio-temporal turning point do images change in meaning, value, and/or audience? Now in a time when images proliferate ad nauseam, the medium of photography speeds towards a precipice of crisis, hinged on its ubiquity, exponentially increased accessibility, immateriality, and now widely understood rehearsed construction. Gonzalo Reyes Rodriguez is an artist based in Chicago whose practice contends with photography’s ails, as well as its history, through a formal approach reminiscent of the Information and Systems artists from the 1960s and 70s. In our conversation, he reminds me that, “photography has always been a medium in crisis,” and that our contemporary questioning of its proliferation is just another point of contention along its conflict-ridden timeline.

Rodriguez’s work is not preoccupied with a medium-specific version of photography as much as its interested in the ambiguous, flexible nature of photographic images and their representation of history. His recent projects have looked back to revolutionary struggles and their post-revolutionary governments, specifically in Mexico and Nicaragua, to confuse the narrative legibility of Latin American nationalisms and their complicated interface with the United States. He employs multiple cultural forms, for example, Playboy Magazine’s 1983 interview with Nicaraguan Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega, or The Clash’s 1980 album Sandinista!, to grasp at a strange and conflicted retelling of history. Elucidation of a singular history is not a desired endpoint. Instead, Rodriguez’s work tests our comprehension of how images become muddied with effect and elasticity when traveling through the complex intersection of culture and politics.

archives, especially those tied to an institution, are always counter to any generative possibilities in reconsidering the information they guard[...] While I’m still in a position to work with these archives for research, I’ve been reconsidering what a photograph can be when the form we know becomes exhausted, what other possibilities are there? In the last couple of years, I’ve become very invested in the writings of Ariella Azoulay and her proposal of photography as a social contract in which we are all implicit, as opposed to a mechanical process where the result is an image.

Your work moves across disciplinary boundaries into sculpture, video, and text yet is anchored in photography, specifically its proximate histories and their malleability. By this, I mean how photographic images once thought to flatly signify truth have become incredibly flexible, prone to sway in meaning and narrative. I want to begin with a question I hope threads throughout our conversation—do photographs still contain truth, and how does your work process this complexity?

What keeps me drawn to photography is how it has always been a medium in crisis. Since its inception and through new points of invention, it has always been contentious. The same questions about changing technologies, truth, and trust have always been posed. I like to think through my concerns from this area of contention. In my own work, I use the ambivalence and contradiction associated with photography as a framework to consider the way history is accounted for, the point at which a photograph turns into a document, and how time changes its meaning.

I think the contention, ambivalence, and contradiction endemic to photography are all essential elements to history’s record as well. I see your work straddling this methodological line between historical research through the lens of culture, and investigation of image value, accountability, and circulation. Your recent body of work uses the United States’ intervention in Nicaragua during the 1980s as a framing device to map geopolitical scruples against various cultural forms (magazine, music, film), celebrity, and states of ongoing crisis—of and beyond images. Can you discuss how your latest exhibition, Scripts of Conflict at a Distance, installed at Roots and Culture in Chicago constellated these ideas? What about this work conveys a sense of ambivalence and/or conflict?

That work began while I was researching for another project and came across the production notes for the film “Under Fire.” It’s a film about Nicaragua during the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) uprising against the Somoza regime and was filmed in Mexico near Red Cross and UN refugee camps for Central Americans fleeing the violence. In that close proximity between the reality of war and its fictional portrayal, I saw a gross embodiment of a conflict between fact and fiction. However, this was also in a larger sense between the utopian ideas of democracy, often used to justify US intervention (see recent coverage of Ilhan Omar questioning Elliot Abrams) and the spectacle of Hollywood war movies. I wanted the conflict to function as a grid or backdrop of failed ideals where I could map out and reference specific instances of contradiction through the process of historicizing. Time also plays an important role in this work because I’m working with material from the recent past, so we are looking at it through the present, simultaneous to witnessing the lasting effects of Central America’s destabilization play out around us. The idea was to register the effect of the material and seek its dimensions in the disorder and complexity of historical memory.

The first casualty of war is the truth, 2018 still photographs from the production of “Under Fire” by Brian McBroom, 1981. The above work on the monitor is Ideology, Infiltration, Interrogation, 2018 HD Video, TRT: 4:02 in loop. Images courtesy of the artist.

The found photographs by Brian McBroom you’ve collected from the shooting of the film “Under Fire” are quite spectacular. They grasp at a certain urgency endemic to crisis and revolution, but the rehearsed quality of the figures is completely apparent in their awkward choreographed poses and interactions (particularly between American and Mexican actors). The material’s affective layers you point out are interesting given you gained access to these photos via eBay, and they are perhaps valued more for American Hollywood nostalgia rather than any proximity to the historical accuracy of the events depicted. I know from previous conversations we’ve had, nostalgia is a method you detest. How do you reckon with the nostalgia so imbued in these black and white images?

I’ve always thought of nostalgia as a neoliberal concept. It’s never good because its a longing for something you can’t get back and remembered in a very specific way that prevents other readings of the time or moment. With the McBroom photographs, I knew when I got them that I had to remove them from their original context for them to work. By using commercial photographic practices like editing down to six images from 54, and then using a window mat to crop and conceal descriptive information that explains the image, I could take it out of its original context and make the images enter a space of uncertainty. Perhaps Gene Hackman or Nick Nolte are recognizable to some viewers but not to others, or maybe the image of the actor hired to play President Somoza has an uncanny resemblance to him, so much so that the image could appear as if it came from a textbook. Through that uncertainty, a sense of reality is both approximated and denied. When fiction begins to resemble reality, there is an opportunity to think about alternative endings.

This temporal element you are trying to harness is difficult when dealing with so many differently positioned narratives. I would imagine this is even more challenging considering these narratives span cultural, fictional, and national orientations. What becomes clear in your juxtaposition, however, is that you are neither seeking resolution of the issue, or a syncing of temporal lines—their confluence retains a disordered state.

Images and other media around Nicaragua I was specifically interested in working with were disjointed, nonofficial, and in some ways lost in time. Obtaining official images and documents specifically on this subject was challenging because of the narratives that government archives and institutions want to uphold. Working with scripts and images from films set during the war in Nicaragua, and Playboy interviews with FSLN members, the Clash’s Sandinista album proved to be more generative. The juxtaposition of this material was intended to disrupt the narrative that history provides.

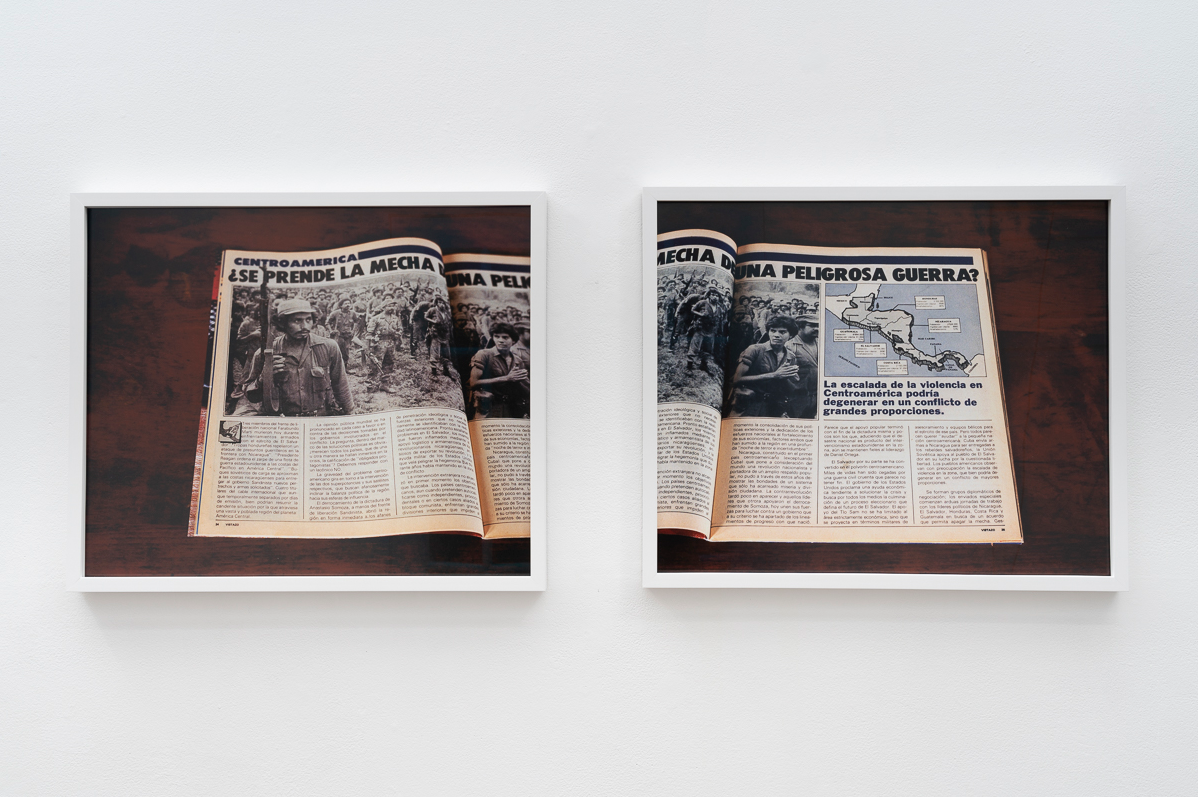

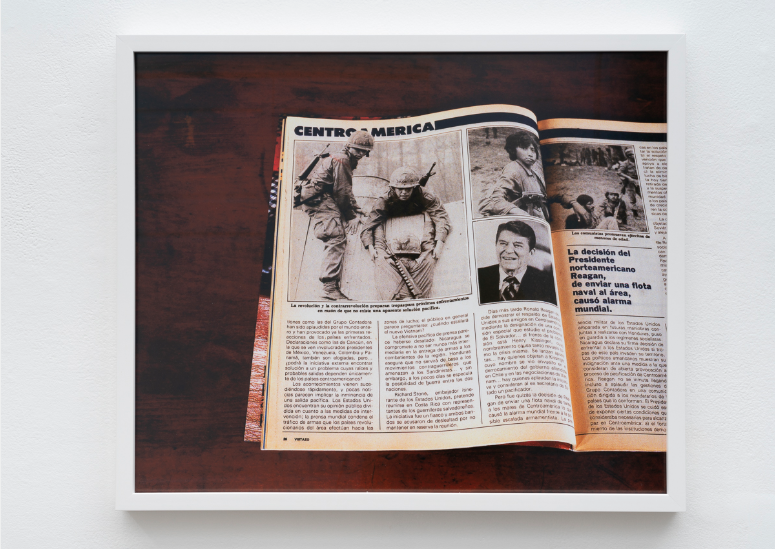

1 month, 35 years ago (Vistazo N° 383 Agosto/83), 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

I’m really fascinated by the limits of the archives you encountered while assembling this project. The archives actually seem to be working against your practice—you want to loosen the narrative binds on these images but their stewards are restricting the stories that can be told. Can you talk a bit more about how this process is orchestrated, and which images garner stringent protections? Have you ever considered making work about this process in itself?

Archives, especially those tied to an institution, are always counter to any generative possibilities in reconsidering the information they guard. Researching material archived by large international organizations and governments such as the International Red Cross, the United Nations, and the Mexican Government proved to be difficult, to say the least, because they all want complete control over the narrative of the images, to the point where the images become inadequate in looking back at the situation. While I’m still in a position to work with these archives for research, I’ve been reconsidering what a photograph can be when the form we know becomes exhausted, what other possibilities are there? In the last couple of years, I’ve become very invested in the writings of Ariella Azoulay and her proposal of photography as a social contract in which we are all implicit, as opposed to a mechanical process where the result is an image.

I use the ambivalence and contradiction associated with photography as a framework to consider the way history is accounted for, the point at which a photograph turns into a document, and how time changes its meaning.

Can you speak a bit more about how Azoulay’s proposal might inform your artistic methodology?

Writers and thinkers like Azoulay, Kaja Silverman, and George Baker helped me rethink photography. At a certain point, I knew I couldn't be a photographer who constructed photographs (i.e. Jeff Wall) or a photographer out in the world responding to their experiences by making images (i.e. Anne Collier). There are so many photographers who do that better than I ever could. However, thinking about photography and its history has become a way to look at my interests and research in a different way.

How does your work with materials related to the Sandinistas signify a through-line with your earlier work? I am thinking specifically of your piece Contrapoder #1, where dialogue from Mexican films about the revolution in that country are read by performers in the present. The scripts are voided from their original cinematic context but gain new meaning in your restaging.

All of the work in Contrapoder is part of ongoing research into the history of cinema in Mexico. It was through researching for Contrapoder that I came across the film “Under Fire,” which spurred the workaround Nicaragua. The films I took monologues from were produced during the Golden Age of Cinema in Mexico. Almost all films produced during that time used the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) as the setting for cheesy love stories. For me, those films were a mystery in that while Mexico went through a democratic dictatorship after the revolution, cinema kept the revolution in a temporal loop. With this work, I embraced a certain ambiguity in order to evoke a tension between recognition and misrecognition, similar to the work about the Sandinistas. I don’t think it's essential for viewers to immediately recognize these monologues, although I do think the revolutionary language used registers as familiar, sometimes even stereotypical.

Your work obviously has political implications for our present moment. Aside from turning to the United States’ current crisis, I wonder about your thoughts on the role art institutions play in all this. What do you think about the current uptick in exhibitions, symposia, and essays on art that are so eager to respond to the United States’ volatile political quandary? How do we distinguish between flimsy attempts at relevance by staid institutions and a genuine desire for equitable change?

It’s difficult to distinguish between the two when there is a new exhibition, presentation or shared syllabus every week, or at least it feels like that sometimes. I always try to consider how the history and information presented is framed. Is it really presenting anything new or a new way of looking at what has always been there? The flimsy attempts always shovel around the same set of knowledge that is stuck in the territory of bad activism and nostalgia for 1968.

When fiction begins to resemble reality, there is an opportunity to think about alternative endings.

You have two exhibitions coming up this summer, which thankfully for winter-weary Chicagoans is right around the corner. At Heaven Gallery in Chicago, you’re in a group exhibition with three other artists, and at Terremoto’s new exhibition space in Mexico City, you have a solo exhibition curated by Jared Quinton. Are you showing the next stage of your work with the Sandinistas or going in a different direction?

I’m still heavily invested in this project, but I am moving away from Sandinistas specifically and expanding outside of Nicaragua. As far as the two exhibitions, for Terremoto I am working with a curator as you mentioned before. The work for that show is further along in progress and has been discussed over time. It is a continuation of the work from Roots and Culture in that it is expanding on the production photography from films similar to “Under Fire.” There’s also a new level to the work because it will be shown in Mexico, a country which hasn’t addressed its own connection to the conflict, or for that matter its history as the bridge from Central America to the US. At Heaven Gallery, there is no curator, which was an intentional decision by the artists in the exhibition. We organized it ourselves and are not bound to a singular narrative around the show. I think that Heaven is an opportunity to exhibit related work, but with the opportunity to take riskier chances.

My last question pulls away from your work a bit because I like to ask artists who in or beyond their networks inspire their own practices. Who is making work right now that you are interested in or inspired by—maybe those working with similar content but through different media or material?

I am definitely inspired by a certain generation of artists who connect form and meaning via documentary practices, as well as institutional critique and the distinction between photo and video. As for artists who are making work right now, I am truly inspired by some of my peers because there’s a specific type of motivation I get when working closely with other artists who are very committed to their work. Two artists that immediately come to mind are Marcela Torres and Jessica Vaughn. I think each of their practices speak to important histories and discourses but through unexpected ways of working. For example, Jessica Vaughn’s work explores the value systems of material objects that are often overlooked, yet have a concrete function or way of operating in contexts of labor and public infrastructure that relate to workers of color. In that work, she makes reference to minimalist sculpture and the system and information artists without relying on the human body to engage corporeal conversations. I feel similar about the work of Marcela Torres, whose performances estrange the viewer and create a sense of discomfort. Through complicating their work either in material presentation or performance there is a space for me to really consider what they are doing and what the work can do. That’s how I want viewers to engage with my work.